Lambert here: I’m hoisting this one paragraph:

But this leads to the main paradox of neoliberalism. Its economic system needs a strong state, even at the expense of constraining democracy, to guarantee property rights and the working of the free market, while actively maintaining the rule of neoliberal social philosophy. At the same time some of its proponents tend to dismiss strong states (Mirowski, 2013). In fact, laissez faire was the last thing neoliberals wanted to achieve. This paradoxical stance towards the state led Milton Friedman, the policy entrepreneur to become an advisor of the Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet to transform Chile into a policy playground.

If there should be “markets in everything,” it follows there should be markets in selling off bits of the state. That works until it doesn’t, as (I would argue) the Tory heirs of Maggie Thatcher are discovering.

By Dániel Oláh, a macroeconomic analyst at Hungary’s Ministry for National Economy, Forecasting and Modeling Unit. He received his master’s degree in economics from Central European University. Originally published at Evonomics.

Social classes have always embraced ideas and social philosophies. Not only to understand and interpret the real world, but most importantly to change it to their benefit. These theories (primarily in social science) have become beweaponed ideas called ideologies, as they are used to influence rather than to understand the human universe. Of course the two are related: the nature of our understanding, i.e. what we consider important and what we leave out from our theoretical framework, is called modelling.

But what if modeling is just an euphemism for modern ideologies? Think of the efforts of neoclassical macroeconomics – for instance, DSGE models – to find the philosophical notion of equilibrium, irrespective of the non-equilibrium nature of the real world, let alone income inequalities. (But also think of Mannheim’s paradox that the critique of an ideology – like this article – is also ideological.)

The great Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek didn’t favor mathematical modeling, but he had clear philosophical models in his head. One of his most famous statements is related to the slippery road to dictatorships: if you introduce a little bit of state involvement in the economy, you have already stepped on this messy road to serfdom. The main intention of this model was to call for action and to raise awareness against the increasing governments in an era when the battle between the West and the East hadn’t yet been decided.

Hayek’s model was working as an ideology in real life, not at all different from that of the Soviet side. At least we get this impression if we take a look at the cartoon version of Hayek’s Road to Serfdom. This was his main work on social philosophy and economics, arguing for individualism and liberalism. Hayek’s argumentation in defense of a minimal state was so powerful that General Motors decided to sponsor the production of the comic version.

So, Hayek’s well-written piece of social philosophy was turned into a black-and-white, stylized world, where keeping the wartime planning roles of the government deterministically leads to the planning of thinking, recreation and disciplining of all individuals.

The support for neoliberal policies by one of the largest companies presents how economic theory is embraced – and transformed – by the big business in the 20th century.

Theoretical Innovations as Part of an Anti-State Ideology

The Keynesian era lasted for a long time, providing stability and increasing real wages for workers. In the seventies, a seismic paradigm shift happened with the returning of pre-Keynesian neoclassical ideas. Roger E. Backhouse (2005) took the numerous reasons for this change into account. The period of full employment lasted for so long that it was easy to forget that it wasn’t a natural order, but the result of conscious policies. In this world, the disadvantages of the market was hidden by active governments, which opened the possibility to turn the critical attention towards the state. Especially in the wake of the new economic crisis that brought stagflation. Keynesian economics wasn’t prepared for such new economic environment just like its neoclassical counterpart was shocked by the 1929 crisis.

The intellectual revolution against the state was building on several new theories, arguing for the ineffectiveness of economic policies. These theories were needed to convince academicians of the intellectual merits of neoclassical economics, allowing them to sympathesize with the neoliberal framework. Milton Friedman argued that active discretionary fiscal and monetary policies are harmful or ineffective because of timing problems among others. As for fiscal policy, the permanent income hypothesis also tried to argue that short-term demand management is ineffective because if they think it to be temporary people save their additional income from the government instead of spending it. New classical macroeconomics was building on the Ricardian equivalence theory to show the same – that a temporary tax cut won’t boost consumption, since people know that they have to cover the costs of that policy later. Friedman also explained the new phenomena of stagflation, stating that people adjust their expectations so that an increasing money supply results in only higher inflation, but unemployment remains the same.

These theories traced the stagflation phenomena back to policy errors of the government. The rational expectations hypothesis argued that economic policy can’t fool people for long since citizens use all new available information rationally when they react to activist government policies. The time inconsistency of governments also meant that discretionary policies may lead to economic harm, so long-term, rule-based policies and commitment to these will be credible and efficient.

Another direction of theories focused directly on the sins of politicians and the government. Public choice theories applied the standard economic theories to politicians and politics, desanctualizing the sphere of politics and transforming it to the area of market forces, emphasizing that decision makers are also just as rational self-interested actors as everyone else. The conclusion was that we can’t expect politicians to determine and follow the public interest. It’s better to restrict them as much as we can – argues James M. Buchanan, Gordon Tullock and George Stigler, who were committed members of the Hayekian, neoliberal Mont Pelerin Society, the cradle of neoliberalism founded in 1947. Tullock developed another theory as well: the concept of rent-seeking to call the attention to the capture of the state by interest groups.

In parallel, new macroeconomic models, like most versions of the real-business cycle theory, visioned an economy where the government has no role to play any more: economic fluctuations don’t mean that there is a problem with the economy. No government, no cry (and always equilibrium) – sings the RBC model of the time.

Neoclassical theorists offered an alternative: the introduction of market forces and property rights in all walks of life. Eugene Fama developed the efficient market hypothesis in Chicago, meaning that prices on the financial market always reflect all relevant, available information. The implication is that the market should be left to itself, allowing company managers to maximize shareholder value for the sake of the whole economy. The impossibility theorem of Kenneth Arrow also proved that the perfect, general economic equilibrium exists, which implies the efficiency of competitive markets.

Arrow developed his theories at RAND Corporation, the Cold War think tank established by the US government, which was a main actor on the theoretical battlefield between the US and the Soviet Union. As Sonja Amadae (2003) argues, several of the theories mentioned above – the rational choice framework – provided the theoretical empowerment of Western liberal democracy with a limited state. She shows that there was considerable governmental efforts in the US after World War II to create new ideas, proving the validity and superiority of liberal democracy in a world where socialist planning was admired also by Western intellectuals and societies.

It’s not surprising that Francis Fukuyama, who was also a member of RAND Corporation, made the political statement in 1989 that the liberal democracy with its neoliberal economic system is the best and final one in our history.

Empowered Ideas in Action

The Keynesian era was ended by an economic crisis, but also by political factors. The big business wanted to achieve a policy change because labor gained strong political positions between 1950 and 1970 (Harvey, 2007). Keynesian employment policies provided strong power to labor unions, which were primary allies in determining economic policies. But this led to the decrease of profit rates. A new globalization, based on the neoliberal thought collective was the reaction of business to its relatively marginalized position in governance to increase its bargaining power (Backhouse, 2005; Skidelsky, 2010). And business groups strongly supported the intellectual revolution (Mirowski & Plehwe 2009), which created the attracting utopia of the market, where the government is a needless actor. In this world, the entrepreneur is the value-creating hero, a completely perfect economic actor, and needs to be strongly supported – by a passive and small state, and also by the rest of the society.

But this leads to the main paradox of neoliberalism. Its economic system needs a strong state, even at the expense of constraining democracy, to guarantee property rights and the working of the free market, while actively maintaining the rule of neoliberal social philosophy. At the same time some of its proponents tend to dismiss strong states (Mirowski, 2013). In fact, laissez faire was the last thing neoliberals wanted to achieve. This paradoxical stance towards the state led Milton Friedman, the policy entrepreneur to become an advisor of the Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet to transform Chile into a policy playground.

The paradox appears when Hayek accepts sponsorship of General Motors. This is so, because he was the main opposition to any kind of planning in the economy. These issues were known by the core intelligentsia of the Mont Pelerin Society – as Mirowski (2013) argues –, but weren’t communicated through the media. The communication that the society is a theoretical descendant of the classical school was clearly false.

This paradox didn’t prevent the Hayekian thought collective to become an ideology. They declared that the main objective was to change the way people think: the main goal of the society wasn’t to develop scientific theories – many different schools of thought were represented in the society – but to save and promote values they believe in. The conscious strategy to become the mainstream was a distinctive feature of the neoliberals.

The appearance of the successful businessmen Antony Fisher symbolized how the big business embraced neoliberal ideas. He was amazed by The Road to Serfdom, so much that he approached Hayek in 1945 at the London School of Economics. Just like David Ricardo more than hundred years before, Fisher wanted to go into politics to influence policy.

Fisher commented to Hayek:

“I share all your worries and concerns as expressed in The Road to Serfdom and I’m going to go into politics and put it all right.”

The response of Hayek was:

“No you’re not! Society’s course will be changed only by a change in ideas. First you must reach the intellectuals, the teachers and writers, with reasoned argument. It will be their influence on society which will prevail, and the politicians will follow” (Hayek, 2001: p. 19).

Although eight society members won Nobel prize in economics, the society hadn’t set high academic standards for its members in order to attract representatives of the big business and other influencers.

To change the ideas of the public, neoliberals created a theoretical building of several floors. The basis is the methodology of positive economics, upon which the economic theories rest. And the final floor is the neoliberal ideology – as Claude Hillinger (2006) argues (this is what Mirowski (2013) calls a Russian doll).

Milton Friedman and George Stigler – with the help of corporate and political support – found the adequate tool to empower their ideas, which was the network of think-tanks, the use of scholarships provide by them, and the intensive use of media. This think-tank network wasn’t for creating new ideas, but for being a gatekeeper and disseminating the existing set of ideas, and the „philosophy of freedom”. Not only Backhouse (2005), but also Adam Curtis (2011), the British documentary film-maker also researched how Fisher created his global think-tank network, spreading the libertarian values of individual and economic – but never social and political – freedom, and also the freedom for capital owners from the state.

According to Curtis (2011), the „ideologically motivated PR organisations” intended to achieve a technocratic, elitist system, which preserves actual power structures. As he notes, the successful businessmen created The Atlas Economic Research Foundation in 1981, which established 150 think-tanks around the globe. These institutions were set up based on the model of Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), a think tank founded in 1955 by Fisher, which is a good example how the marginalized group of neoliberal thinkers got into intellectual and political power. Today, “more than 450 free-market organizations in over 90 countries” serve the “cause of liberty” through the network. The network of Fisher was largely directed by the members of Mont Pelerin Society (Djelic, 2014).

So we could add an imaginary upper floor to the neoliberal building, through which the commentators of seemingly independent think tanks represented very similar ideas – without informing the public that in terms of ideologies, it’s not free to choose. At the same time, as Mirowski (2013) shows, the network promoted itself towards investors arguing that companies should invest in the production of transformative ideas, becoming policy products for final consumption in the end. (These investors are called edupreneurs by Rob Johnson (2017), who gives a revealing account of how philantrophists recreated the new parton-client model of the Renaissance in modern science.)

The second-hand dealers of ideas could indeed make a political difference. As Oliver Letwin British MP argued: “Without Fisher, no IEA; without the IEA and its clones, no Thatcher and quite possibly no Reagan; without Reagan, no Star Wars; without Star Wars, no economic collapse of the Soviet Union. Quite a chain of consequences for a chicken farmer!”.

Achieving a Successful Upward Redistribution

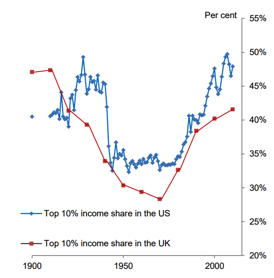

The neoliberal ideology was successful from the perspective of the big business. The eighties is marked by the start of declining wage shares all over the world, as the distribution of produced added value reflected the strenghtening of global capital. These years also meant the start of opening of the real wage-productivity gap, resulting in a previously unseen phenomena, the stagnating incomes of the middle class. At the same time, as a result of tax decreases inspired by the neoliberal political program the income of the top 10 percent started to increase dramatically in Great Britain and in the US, which were the homeland of the neoliberal counterrevolution (Alvaredo et al., 2013; Piketty-Saez, 2014).

Source: Haldane (2015)

The policy mistakes, arising from the philosophical and ideological nature of the neoliberal economics to achieve deregulation, were reflected in the increasing number of financial and economic crises. Margaret Thatcher, who once contributed to the development of libertarian think-tanks personally, having seen the soaring unemployment rates despite the implementation of neoliberal set of policies, argued in 1985 that she never believed in monetarist theories. The Washington Consensus, based on static neoclassical economics, turned a blind eye to the dynamic phenomena of institutions, thus contributed to the deep recessions in post-socialist countries in Central Europe. “The point for neoliberalism is not to make a model that is more adequate to the real world, but to make the real world more adequate to its model” – argues Simon Clarke (2005). Meanwhile, according to David Colander (2004), neoliberal economics reversed the attitude of classical thinkers, concluding that markets are the best, while their predecessors in the 18-19th centuries were stating that markets are the least of all evils.

Neoliberalism created the (econo)mist of scientism and economism, decreasing pluralism in economics. These mechanisms to indoctrinate young scholars into the simplistic but often irrelevant models are needed to stabilize the scientific paradigm and the social-economic system built on it (Earle et. al, 2016; Kwak, 2016). This distinctive feature of this system – as Dean Baker (2016) shows – is the protectionism of the capital owners and the maintenance of upward redistribution towards them, at the expense of wage growth of the labor force – this is why neoliberalism needs to capture the state.

But what is behind the neoliberal (econo)mist? Let’s hope that it’s not the road to serfdom.

neoliberalism is neofeudalism. Savings defeats rent-gathering. Savings bad. Bad consumer. Need more debt.

Also, parton-client? Suspect a typo.

He surely meant “patron-client” relationships, which were very important to science in Europe the 16th-19th centuries when there were no funding agencies of the kind we have today, such as NSF, NIH, etc. It’s a bit disheartening to think that we are moving back in that direction.

Good to see Adam Curtis getting a mention – a trawl through his history of documentaries catches most of the rotten fish, particularly for the UK.

100%…here is Adam Curtis, BBC documentary historical on Margaret Thatcher economics of “neoliberalism”:

(part 1 of 4)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=234H8X1-JiA

(Lambert): “If there should be “markets in everything,” it follows there should be markets in selling off bits of the state. That works until it doesn’t, as (I would argue) the Tory heirs of Maggie Thatcher are discovering.”

In the seventies, a seismic paradigm shift happened with the returning of pre-Keynesian neoclassical ideas.

The “Backhouse (2005)” link in the first paragraph of the section “Theoretical Innovations as Part of an Anti-State Ideology” is no longer valid. Although its 2009 publication shows it’s not the precise article Oláh cites, it appears that this article by the same author nicely summarizes the same material. It’s an interesting read and not too long given the history it covers.

Thank you

If NeoLiberal is going to exist as a legit critique, and not some congealed meme mass along the Libertarian or reactionary line, it’s going to have to build some specific, some special things.

Nobody ever wrote a 1980somethung dissertation ‘NeoLiberalism, a way forward’ With only a negative and No positive statement, it’s only best possible revisionism.

It doesn’t yet join common observations , I can list a dozen (no space) with a set of mid level frameworks. For extra credit, lock down the prose a little & pour on some consensus & juicy data

From that perspective, all one has to do is look at the gross failures of the ‘econometric models’ that neoliberal economists embraced.

Exhibit A is those economists who ran around in the early 1990s waving the output of econometric models that ‘proved’ that NAFTA would raise wages and living standards for workers in both Mexico and the United States.

Exhibit B is those economists who promoted deregulation of the California electricity market in the late 1990s, again based on neoliberal ideas such as the one cited in the article:

The impossibility theorem of Kenneth Arrow also proved that the perfect, general economic equilibrium exists, which implies the efficiency of competitive markets.

Exhibit C is deregulation of the financial industry in the late 1990s, elimination of Glass-Steagall rules on separation of investment and commercial banking, which set the stage for the 2008 economic collapse, again based on neoliberal economic ideology.

The conclusion, really, is that today’s academic economic discipline is highly flawed – it is barely descriptive, with zero predictive value. The above quote about the ‘impossibility theorem’ – this is the kind of thing that ecological sciences examined and dispensed with many decades ago. For example, theories about ‘ecological equilibrium’ gave rise to fire suppression strategies; today ecologists recognize these were flawed, that natural disturbances (fire, landslides, etc.) are a fundamental feature of ecological systems.

Incidentally, isn’t this why economists are sequestered away in business departments in academic system, so that they don’t have to face real scientific criticism? Econometric modeling is nothing but garbage based on false assumptions – but how many academic economic careers are built on such dissertations?

That’s the objective of a well paid economist. Produce the correct form of mumbo-jumbo which suits you clients’ end, and retire into a well paid environment, such as President of Harvard.

Economics is for “might makes right,” not about truth in the “scientific method” sense.

Yes and I also believe in the tooth fairy.

About Exhibit B – California energy deregulation: did someone say ‘Enron’?

https://www.creators.com/read/molly-ivins/05/06/molly-ivins-may-30-03b7ab17

“Benevolent dictatorships” involoving some form of serfdom (actual or virtual) are the norm through human history and can be quite stable and productive (England, various Chinese dynasties, Italian city-states). Time will tell if present day benevolent dictatorships such as Russia, China or Vietnam will also be. Non-benevolent dictatorships (Aztec, Mayan, Mongol, Stalinist) did not. Syria is a toss-up, but illustrates the unpredictability of human behavior; the govt there largely left you alone if you kept quiet (as opposed to the extreme example of say N. Korea ), but look what happened.

Here in America the Neoliberal BeneDicta is Wall St/Global Cap, and the Young Turks of that class (the Fang & other tech billionaires – and it is a class ) lead the charge for the universal basic income, similar to free bread for Roman citizens 2000 years ago. And is the universal hand-held device (free in America if you’re poor), used primarily for distraction, gossip and entertainment really all that different than free admission to the Coluseum?

But will it work?

… as was written on a Roman drinking cup from the late 3rd Century Rome:

“VITA BONA FRVARVR FELICES”.

“But what if modeling is just an euphemism for modern ideologies?”

If the model is fuzzy, say 70 pages of words with signs of 2nd derivatives and no fixed points, you can guarantee you’re curve fitting and thus just mathematizing ideology.

If you give yourself a hard problem, with clear values and only a few words where you can really check whether you’re fooling yourself, then it’s not. Ask Feynmann about this.

But a lot of economics papers look like the first — I see pages and pages of words, then a curve that would fit almost anything, then words and word, finally a few tables and an exercise in curve fitting.

That’s the issue with soft sciences — people tend to cheat with math.

Ha Joon Chang wrote an exellent book, “Economics: The User’s Guide” which has a few choice quotes on that issue:

If we take ecology, for example, the recolonization of an area destroyed by volcanism, it’s very hard to predict the exact species composition that will eventually result. We generally don’t think of plants, insects, birds, etc. as having much ‘free will’, either. So predicting what humans will do is clearly more difficult. A comparable economic problem is what the recovery from war or depression will end up looking like. Anyone claiming to have ‘hard mathematical forecasts’ for such future outcomes – well, they’re just trying to sell you something. “We base everything on hard math” is just a marketing tactic. As Ha Joon Chang further notes:

I would suggest they are engaging in a form of intellectual subterfuge. They know that a pretentious sprinkling of math on anything tends to limit mainstream critique, and hardens claims into “indisputable facts” (facts that, by implication, were arrived at with scientific rigor as the guiding principle). Pull out a paper with some curves and formulas in it, present its contents as “laws of economics” and yourself as an expert, then you’ve gone a long way towards quietening dissent and extracting consent. It’s when such unquestioning consent comes from our ruling classes that we run into trouble.

Long ago when I took a course on the calculus of variations [a topic I never really understood and never used — but which I believe to be extremely important as an area of knowledge and study — one of many I regret having ignorance of] the professor — in the mathematics department — often commented about how frequently he encountered bad mathematics and false reasoning used in the mathematics he reviewed in economics papers — papers he had sometimes scoured looking for examples to use for the textbook he’d written [a truly excellent textbook now available from Dover Books]. He said the economists seemed intent on mis-using Hamiltonians where a more simple use of the calculus of variations [simple for him — ugh!] would have more easily provided an answer and also revealed the errors in their models.

I see at least 3 internal contradictions or logical inconsistencies in the so called neo-liberal policies.

1. State is essential to protect “the interests” , but not to the extent of promoting “the rest”. It is a delicate balancing act in framing the laws and regulations. Sometimes, these laws come back to haunt “the interests” themselves. – unintended consequences.

2. interests of Oligopolies are to be protected as the cost of perfect competition – in the name of free markets and market competition !!!

3. These policies result in monotonically increasing level of concentration of wealth and power. The end result will be only a handful of people will ultimately own the entire wealth in the world. The top 10 percenters will end up being losers to the top 1 percenters and the top 1 percenters will also end up being losers to the top 0.1 percenters and so on. It is like killing the goose laying the golden eggs.

Simplify — the Market knows All. If at first policies fail — build a better Market — and if that requires the coercion of the State how is that a problem?

If the top 0.1 percenters own the entire wealth in the world — how is that a problem? As for geese laying golden eggs — who cares as long as you have enough golden eggs to make all the ducks stand in line and march to your songs.

Deflects blame, shifts criticism, and avoids responsibility. It’s as factual as saying “its god’s will,” and equally effective at dismissing any attempt for change.

“The impossibility theorem of Kenneth Arrow also proved that the perfect, general economic equilibrium exists, which implies the efficiency of competitive markets.”

Cite? I thought Arrow’s impossibility proves that all general voting system can fail to satisfy perfect justice, by his axioms of perfect justice for voting (transitivity, et al). I don’t see how that proves general economic equilibrium, given that in general most theoretical systems fail to have a stable equilibrium — steady state is an exception, not a general condition. Or is there another Arrow’s impossibility theorem?

Thanks! That bothered me too.

I scrolled through comments just to see if anyone had caught that whopper. The author had confused the “impossibility theorem” with the Arrow-Debreu GE model, the ancestor of DSGE. At most you could say that the impossibility theorem foreshadows latter “public choice” theories. But Arrow himself was apparently a kindly man of social-democratic preferences. Which just shows how commitments to formal-instrumental “rationality” can belie other normative commitments. It seems to have been an existential paradox, an “impossibility”, that Arrow was not equipped to deal with.

That’s interesting — but if that’s the basis for current economics, it’s just a trick. It assumes a convex manifold — and obviously that makes everything easier, that you can just do a gradient descent to find the minimum, and that there is a global minimum.

But it doesn’t tell you that the minimum is stable — then the first order differential needs to be convex too, right? And why would the manifold of consumer preferences be convex at all? Especially given that the manifold must be dynamic, since preferences change all the time.

It looks like the Gaussian copula all over again. “Let’s assume that all chickens are spherical”, which is fine enough from a far enough distance — but we’re not at a far enough distances, we’re trying to measure the behavior of a small number of chickens nearby under non-equilibrium conditions.

All these assumptions — they’re a place to start. But if we’re still using crappy assumptions that people used as a start more than 50 years ago, the field is really doomed. Worse than useless, positively dangerous by burying their failed assumptions.

DSGE looks a bit better — but is anyone running massive simulations of dynamic stochastic systems in economics (other than DE Shaw and private hedge funds)? I don’t know of them — there’s lots of work in other fields that are trying massive simulations of their dynamic non-equilibrium systems, but not apparently economics. Is there just no point?

And given that sampling non-equilibrium systems takes exponential time relative to outliers, are people aware of how far off their samples are?

Yes, GE theory is full of unrealistic assumptions and is logically inverted, based om perfectly competitive markets as price-setting mechanism without any explanation of how they would come about and wishing away the organization of non-market production systems as merely a matter of market inputs and outputs. It’s more a jejune mathematical fantasy than a social scientific theory.. There are economists working in disequilibrium dynamics, but as you know the mathematics is much more difficult. Here’s one, the German economist Peter Flaschel, who is reputed to have mastered the math, though that’s beyond my pay grade:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/list/623967.Peter_Flaschel

Too much passive voice, a little shy on agency. Think tanks, for example, were not “found”, but created by the patrons of neoliberal academics, rather like taking their ribs and forming new partners, whose utterances needn’t survive the rigors and self-criticism of traditional academic life.

As Mirowski and others contend at length, neoliberalism is a political tool for those desiring the outcomes it espouses. A “self-regulating” market, a contradiction in terms, is a market substantially controlled by its strongest actors. By neoliberal definition, that excludes government. As Klein argues, its policy experiments sometimes had to be implemented at the point of a gun (Friedmanites in Chile, Argentina, Brazil), owing to their consequences being so obviously against the interests of so many.

Now that neoliberalism has become the established church, it will take a reformation to dislodge it. The predictable response will be that we should follow a diet of worms.

The phrase “the road to serfdom” implies we are still on it. I suggest instead, that for most people, we are already “there.” We may not be “tied to the land” but we are tied to a pre-existing “job,” one that pays just enough to keep us alive and not too disgruntled. (If you don’t work, you don’t eat. We can own land, but not enough to be self-sufficient.) The option of living off the land no longer exists because all of the land is “owned” now. So, like serfs, there is nowhere to go where the options are different. There is no road out of serfdom. As much as the elites like to beat the drum of entrepreneurism and social mobility, these things do not exist for huge swaths of our society.

Civilization was created so the many could serve the few. Civilizations were created by religious elites and carried on by a coalition of religious coercion and physical coercion: the basic equation was to get the “subjects” to produce a surplus which the elites would confiscate so they could live (usually as lavishly as possible). Slavery and war were upscaled to feed the system.

Has all of this changed because iPhones? I suggest not. Slavery still exists, wage slavery exists, poverty is still prevalent, and the rich keep getting richer. Is this what civilization is for? Any outside observer would have to conclude that any other goal for civilization is not yet observable.

But advances in energy, nutrition, public health and other sciences have made life much easier and actually occasionally enjoyable for untold millions whose ancestors were truly dirt poor.

The question is, will the advances be enough to prevent violent revolution? England, Spain, Japan, Argentina, Thailand dodged violent class-based revolution, while France, Russia, China, Bolivia, Haiti, Vietnam, Cambodia and Iran did not. I don’t think it’s truly predictable for a given society.

Re the above and yesterday’s discussion of neoliberalism–while it’s been a long time I recall many of the arguments put forth by the Washington Monthly crowd who became the journalistic spearhead for the revival of neoliberalism–Democratic party version. Charlie Peters and his acolytes saw what they called neoliberalism as a reform movement. Some had also been involved in Ralph Nader’s consumer groups and the thrust was that large institutions in both government and business had become ossified and inefficient. The Big Three auto makers were the poster children for this with their exploding Pintos and low quality cars made by supposedly indifferent but union protected laborers. From this perspective the reduction of regulations was a way of encouraging competition that would make entrenched bureaucracies accountable. Kahn’s airline deregulation for example was promoted as a boon that would benefit travelers by reducing airline ticket prices (and it did for a time). I’m not sure the movement could simply be put down as a plot by business interests. The Washington Monthly’s Peters claimed to be an old style FDR liberal.

But as in Orwell’s Animal Farm, the revolutionaries quickly became overlords and as corrupt as the institutions they were criticizing. Many moved to Peretz’ New Republic–not exactly a hotbed of idealism.

Perhaps the takeaway is that theories matter less than the quality of the individuals involved. These days the leadership ranks of both parties and the academics who support them very much need the boot.

Peters’ Neoliberalism has no relationship to Hayek’s Neoliberalism, apart from both being descendants of classical Liberalism (which should not be confused with liberalism).

Unlike Hayek, Peters was not supported by big business and his movement faded away in a few years.

I’d say Peters’ neoliberalism has everything to do with the form of neoliberalism espoused by people like Al Gore. As the above article points out the revival of neoliberalism was accomplished with heavy media support–not just by advocates in wonky economic journals. The “reform” mantra gave cover to self-described liberals who were advocating a conservative program.

Liberalism (big L) is a conservative ideology. Peters was just a little more liberal (small l) than von Hayek, who would probably have regarded him as a Socialist because Hayek was an extremist nutter.

When the Al Gores of the world say “I am a Liberal” they don’t mean “I am liberal”, though they are happy for liberal voters to assume that.

It’s likely that many of the people we now call neoliberals have never even heard of Hayek unless they read economics blogs like this one. Whereas The New Republic–where many of Peter’s disciples landed–was very influential during the 1980s as the current version of neoliberalism was coming into its own. My contention is that the people who popularized these ideas are more significant than the rather obscure figure who first used the term.

And whether Al Gore is a leftist is not the point. He was a Democrat, and it was necessary for our ostensible leftwing party to take a different approach than those Repubs who wanted to drown the government. Gore was out to “reinvent” it.

Awareness of gatekeeper roles and their ramifications is one issue of grave concern to many citizens. There are variations of the role playing in different parts of society whether in the Ivory Tower, Think Tanks (self-designated with initial capitals), media or other areas. Recently, that role in media has come under scrutiny as seen during and after the US campaign and election. Who gets to control what appears as news, and will the NY Times editorial board cede any of that, for example?

The increasing impact of social media in dissemination of information and use of influencers represents a type of Barbarians at the Literal Gate. The boards and think tanks won’t easily relinquish their positions, any more than the gatekeepers of prior eras would willingly do so.

This era is unsettling to the average person on the street, and particularly to those living on the street, because they have been told one thing with certainty and gravitas and then found out something else that was materially opposed. In the meantime, truth continues to seek an audience.

The assertion you selected from today’s post seems clearly false to me. The think-tank organizations definitely create new ideas and often conflict with each other. Their topics and views also tend to dominate discussions and steal the oxygen from outside ideas.

They are schools of agnotology flooding discussion of every policy with their “answers” and contributing to the Marketplace of ideas.

As flora points out in yesterday’s George Monbiot/Gaius Publius neoliberalism thread, Hayek and Mieses grew up under Habsburg absolutism; Ayn Rand grew up under Romanov absolutism. All that they knew of the actual non-theoretical experience of democracy and free markets came from the insecurity of coming of age under the chaos of the collapse of those two empires during the break to re-arm during 1919-1939 in what should be seen as a single 1914-1945 European war.

The founders of neoliberalism appear in these descriptions to suffer for a nostalgia for pre-war absolutism that self-interested western capitalists have been happy anoint themselves to fill. Their alien neoliberal ideology is nothing but absolutist-nostalgic garbage, shoved down the throats of its victims via simplistic but well-funded propaganda. Neoliberalism’s false premise of the benevolence of the absolutism of wealth is quite literally the road to serfdom for the rest of humanity.

Interesting point. Von Mises was born in 1881, so his formative years were definitely under Habsburg rule. Hayek was younger, born in 1899, so he started out under the Habsburg thumb, too. Rand is a little more complex. She was born in 1905, and came to the U.S. in 1926, so she experienced both Tsarist absolutism, Communist absolutism, and sheer chaos.

As you point out, none of the three had any early experience with democracy.

The kleptocrats of the world are struggling to find a workable power sharing solution to keep their rule intact. The power of the neoliberal order is that it has beguiled the masses into believing that satisfying short term personal wants constitutes a meaningful social order. The constant churn and turnover of consumer goods is the purpose of life instead of participating in the construction and maintenance of lasting, stable social institutions and customs. This is the culmination of turning citizens into consumers. It is a different form of bondage and slavery. The perfect system of enslaving oneself.

The trouble with the neoliberal order its that the old tools in maintaining its power and relevance are reaching limits. As technology democratizes the use of force, it is more difficult to impose ones will. Also, as the weapons become more devastating, their use would instantly disrupt the entire network supporting the political structure. Imagine the consequence of a nuclear exchange. Neoliberalism needs an existing social structure upon which to deploy its parasitic ideology and methods. As Michael Hudson aptly described in his Killing the Host, once that social structure is weakened or destroyed, neoliberalism will be incapable of functioning. It would have to become naked totalitarianism in order to survive.

The question has always been how do you justify and deal with inequality. With human stupidity, climate change, and planetary resource depletion bearing down on every society, how that question is answered rises to the fore and cannot be papered over with greater reams of propaganda. It seems we are once again on the verge of a truly Revolutionary era- like it or not.

Since the 60s all of our Big Boondoggles like Star Wars were embezzlements. The neoliberal mandate quoted above “The point for neoiberalism is not to make a model that is more adequate to the real world, but to make the real world more adequate to its model” is pure hubris. And it has finally run its course by serving us all up a big fat mess. It is very encouraging to see this essay cite so many recent analysts. It’s beginning to look like critical mass. Most of us are thinking about the stock market these days and anticipating a downturn if not a crash. But what if they triggered a crash and nobody came? What if the stock market just stagnates and sits there? The only buyer these days is the Fed but the Fed might refuse to “expand its balance sheet”. And in perfect circular logic, this prevents the stock market from crashing because nobody’s buying. And where does this leave neoliberal economies and their governments? It will be a tad embarrassing. And also too what if nobody wants to become a worked-to-death entrepreneur with a crappy idea just to make a profit and keep running the squirrel wheel? We don’t have to be a capitalist, socialist, or free market society at all. The only thing we are required to be is just. Constitutionally.

…love your commentaries, STO, but are we really avoiding the american imperialism aspect, the “total global military domination” neocon “Project for A New American Century” aspect of imposing economic exploitation, as described here, by John Perkins:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j1IvMLTQ6ew

and here, with regard to Dulles CIA historical documentation?:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORapPwla7fs

..can we really be surprised it has “come home to roost?”

Or selling. If nobody’s buying, and some are selling, that trend is like going over a waterfall. One starts slowly, but does not die until the bottom.

“The question has always been how do you justify and deal with inequality.”

You should take a look at the new book by Walter Scheidel “The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality ” which argues that military mass mobilization has turned out to be a promising mechanism for generating substantial reductions in the gap between rich and poor. He argues that this most intense type of warfare is most likely to compress income and wealth disparities.

He also argues, quite persuasively, that the most intense revolutions, the one in Russia and the one in China, all succeeded in leveling on a grand scale.

One further vehicle of leveling is what he calls state collapse which tends to destroy disparities as hierarchies of wealth and power are swept away.

The logic of the Scheidel analysis moves from ongoing advances in economic capacity and state-building to a propensity for growing economic inequality which ultimately produces political advantages that tend to perpetuate the position of certain elites which then exacerbates the creation of further inequality.

Scheidel also largely dismisses peaceful movements for social justice like democracy, extension of the franchise, education, social democracy and trade unionism as having, at most, a trivial effect on inequality.

Is this the reality that we face–that only massive and violent disruptions of the established order result in an meaningful leveling and that the social cost of choosing such disruptions makes such a choice catastrophic in its consequences?

I wish you were right that “… the neoliberal order … [is] reaching [its] limits” but I am afraid your observation: “It would have to become naked totalitarianism in order to survive” — may be all too true and all too likely. I’ve been trying to come to grips with what a “… truly Revolutionary era- like it or not” — could mean.

…militarization of police depts, financialization of U.S. economy, international military imperialism, technological intrusion-observation of everyone’s lives, defines…

The Keynesian truth seems highly classified top secret material. That the first two postulates of the Ricardian theory are flawed, should not be spoken of. Neo-liberal mantra dictates life and evolution itself at some point, wealth dictates the ability to procreate.

Unfotunately for the neo-liberal elite, the end of the “endless” expansionary period of the “new” industrial age ( globalism ) has come, just as it had at the end of the development of the United States. Demand, it seems, once again, can no longer equal supply. The reward ( wage unit ) no longer far outweighs the disutility of labor, no more is it marginal, and gone is the efficiency of capital. The great casinos in the sky have crashed and burned, replaced with a hollow shell of freedom, or perhaps it is only the lie of it. A rich man gambled greatly on those casinos falling down and it is an even more rich man who gambles with him on ever greater portions of real estate, blood, slavery and tax cuts. Perhaps savings indeed should equal investment. Investment in our children and society. Critical thinking, our greatest unit of trade value, even until disposable neo-liberal ideology has been washed away by the ever changing tide of common sense.

…”it” didn’t “end” in Chile’, where-when (Sept. 11, 1973) Naomi Klein noted CIA, Friedman-“Chicago Boys” imperialism imposed “it”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORapPwla7fs

Economic philosophies come down to questions of morals and ethics: what is ‘good’ and why; what is ‘bad’ and why? (These questions often come down to the philosophical questions about “the one and the many”*)

Some (brief) history of moral philosophy in business, or markets:

“Plato is known for his discussions of justice in the Republic, and Aristotle explicitly discusses economic relations, commerce and trade under the heading of the household in his Politics. His discussion of trade, exchange, property, acquisition, money and wealth have an almost modern ring, and he makes moral judgments about greed, or the unnatural use of one’s capacities in pursuit of wealth for its own sake, and similarly condemns usury because it involves a profit from currency itself rather than from the process of exchange in which money is simply a means. ….

…

“John Locke developed the classic defense of property as a natural right. For him, one acquires property by mixing his labor with what he finds in nature.7 Adam Smith is often thought of as the father of modern economics with his An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Smith develops Locke’s notion of labor into a labor theory of value. In modern times commentators have interpreted him as a defender of laissez-faire economics, and put great emphasis on his notion of the invisible hand. Yet the commentators often forget that Smith was also a moral philosopher and the author of The Theory of Moral Sentiments. For him the two realms were not separate.”

-Dr. Richard T. DeGeorge

https://www.scu.edu/ethics/focus-areas/business-ethics/resources/a-history-of-business-ethics/

Now to this article:

“The great Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek didn’t favor mathematical modeling, but he had clear philosophical models in his head. One of his most famous statements is related to the slippery road to dictatorships:….”

This is a moral claim or ethical claim: Dictatorships are bad.** Well, I accept that statement. I judge dictatorships bad. I do not want a dictatorship oppressing me or my fellow citizens for any reason.

Hayek feared oppression from an unchecked left, imo.

Again, from De George:

“Marx claimed that capitalism was built on the exploitation of labor. Whether this was for him a factual claim or a moral condemnation is open to debate; but it has been taken as a moral condemnation since ‘exploitation’ is a morally charged term and for him seems clearly to involve a charge of injustice. Marx’s claim is based on his analysis of the labor theory of value, according to which all economic value comes from human labor.” (ibid- from link above)

No doubt the old USSR became despotic, supposedly in the name of ending exploitation of labor. (Gulags?)

Back to Olah’s paper and definitions. The following line could be rewritten to fit the Marxist USSR moral claims with no loss in accuracy.

“But this leads to the main paradox of

neoliberalismcommunism. Its economic system needs a strong state, even at the expense of constraining democracy, to guaranteepropertyworker rights and the working of thefree marketcommunal, while actively maintaining the rule ofneoliberalMarxist social philosophy.”It’s easy to imagine neoliberalism leading to the same despotic conditions in mirror image of the old communist states. Crushing individuals in the name of Market Rights and neoliberal market philosophy, from an unchecked Marketism.

——————————–

* “The question which haunts the dialectical culture is this: how to have unity without totally undifferentiated and meaningless oneness? If all things are basically one, the differences are meaningless, divisions false, and definitions are sophistications, in that the tyranny, or destiny, of oneness is the truth of all being. [my aside: neoliberalism]But, if all things are basically many, and if plurality is ultimate, then the world dissolves into unrelated particulars and becomes, as some thinkers insist, not a universe but a multiverse, and every atom is in a sense its own law and being. [communism] The first leads to the breakdown of differences and the liberty of atomistic individualism and particularity; the second is the breakdown of fundamental law into nihilism and the retreat of men and their arts into isolated and private universes”

― Rousas John Rushdoony, The One And The Many: Studies In The Philosophy Of Order And Ultimacy

corrections in footnote *paragraph: [My aside:

neoliberalismcommunism]and [

communismneoliberalism]Longer comment in moderation.

Shorter comment:

“The great Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek didn’t favor mathematical modeling, but he had clear philosophical models in his head. One of his most famous statements is related to the slippery road to dictatorships:…”

Dictatorship is a bad and an immoral form of government – whether from the left (communists) or the right (Marketists). Hayek and neoliberals only consider the danger from the left, not from the right. This is moral philosophy, as Adam Smith knew. A technical claim for efficiency is not a moral claim to justice or the good. There is no moral claim in neoliberalism that withstands examination. imo.

..flora…one must decide whether Hayek “ideas” were aimed at actual ideology, or favorable subsidization by those whom he knew would be “favored”…?

ha. indeed. what is the term of art used for such economists ? “Entrepreneurial” economists ?

adding: wonderfully convenient how claiming “the market knows all” absolves one of moral agency.

…”the artist forgoes creative intuition at exact moment he-she becomes aware of impression about to be made…”

…then again, a dear international artist-friend intoned when thoughtfully considering quote, “hmmnn…all well and good till you draw the first line…”

..seems to me the “cover-up” has been going on since “the first line was drawn”…

It may be time to revisit the socialist calculation debate of the mid-1930 where, over a period of vears, von Mises and von Hayek debated socialist economists like Oskar Lange and A.P. Lerner.

Mises argued that capitalism allowed for a much broader participation in decision-making than that permitted by the cult of nationalization and planning. At that time much of the Left chose to ignore this critique by pointing to the evidence of capitalist failure and apparent Soviet success in rehabilitating the Soviet economy and embarking on a road to industrialization.

Lange responded to Mises’s challenge by conceding that planning, even carried out by the most democratic of governments would lack proper economic criteria and that to prevent a relapse into more authoritarian solutions, socialist planning authorities would need to develop a simulated market with a system of shadow prices that could be used to compare different paths to development

Hayek, in the early 1940s, further developed the Austrian critique through his argument that collectivist ownership would erase responsibility for investment decisions making it impossible to accurately assess the responsibility for mistakes.

Hayek also pointed to the fragmented and dispersed character of economic knowledge, and as as Mirowski has argued in his new book “The Knowledge We Have Lost in Information,”– managed to establish the first commandment of neo-liberalism “that markets’s don’t so much exist to allocate given physical resources so much as to integrate and disseminate something called knowledge.” and “… that the market ceased to look like a mechanical conveyor belt and instead began to take on the outlines of a computer.”

Mirowski adds that It was this new image of markets as superior information processors that has apparently swept everyone along from-neoclassical theorists to market socialists.”

Is it true that the Austrian critique can only be met by a case for socialist self-management and .public enterprise that bases itself on the dispersed character of economic knowledge and refuses the tempting delusion of a totally planned economy?

How does the Left today respond to the Hayek/Mises arguments of the 1940s, with their attempted vindication of entrepreneurship, risk-taking, innovation and the need to make economic agents responsible in the use of resources?

…by historical documentation of what has come of their own postulations:

(Monbiot):

“Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.

Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve.

We internalise and reproduce its creeds. The rich persuade themselves that they acquired their wealth through merit, ignoring the advantages – such as education, inheritance and class – that may have helped to secure it. The poor begin to blame themselves for their failures, even when they can do little to change their circumstances.”

(“neoliberalism” has been u$ed to destabilize relative economic and social stability of FDR “New Deal” 60+ years…)

“How does the Left today respond … ?” Very good question! I would add to that “How does the Left respond to the Market as an epistemology?”

I’ll attempt a half-assed answer to the question of “… attempted vindication of entrepreneurship, risk-taking, innovation and the need to make economic agents responsible in the use of resources?” [The question I posed is highly problematic for me. Once I accepted Mirowski’s assertion that Neoliberals really truly believe this nonsense of the Market as an information processor — an arbiter of the Truth — I was flummoxed. I cannot argue with what to me is absurd. However Mirowski convincingly argues that addressing the central absurdity of the Neoliberal Ideology is crucial to any argument with its true believers.]

I’m very old fashioned I admit. I believe humankind has a number of personality types each suited to select and fill various niches in society. There are builders and makers of things. There are those who empathize and care for others. There are those who like to grow things and raise and care for animals. There are those who invent and make new things and think new ways. There are those who teach. There are those who conserve — and those who break away and cast out in new directions — pathfinders. There are those who like to decide and direct as well as those quite happy to follow reasonable direction. This is the merest thumbnail sketch but you should see the flesh of a very old concept of human society.

The entrepreneur is but one more type of individual in human society. Entrepreneurs are neither special not specially deserving of acclaim or riches. However what they do is useful. Society benefits by sharing a small portion of resources to entrepreneurs while also absorbing some of their risks of failure so that both gain. If an entrepreneur achieves success that benefits society and there is little cost in sharing a somewhat greater part of that gain with the entrepreneur as an encouragement. I have met and known some I regard as “true” entrepreneurs. They did indeed hope to make a financial gain from their efforts and risk — but that was NOT what motivated them. That was not their core.

The classic Liberal notion that an entrepreneur deserves and has right to all of the gain from their actions is very difficult for me to argue. Like the Neoliberal notion of the Market as epistemology this Liberal notion strikes me as an absurdity. I am again flummoxed.

…the “entrepreneur” (Ernst Becker’s “innovator” – “Structure of Evil”) has at his disposal great social contract, supply of “the commons” to base his agency upon. He is completely aware of this. That he refuses indulge, evaluate, or socially consider said reality, defines actual intention.

I also share a similar outlook on human society and have always found the classical and neoliberal hagiography of entrepreneurs risible from the very moment I started to acquaint myself with this pseudo-science called economics.

I found this post very confusing and it stimulated what to me is a confusing maelstrom of comments. I’ll stick with the title of this post rephrasing it as “How Economic Theories Serve the Power Elite”. I don’t believe the Rich and Big Business are equivalent to the entirety of the Power Elite but I do believe they have achieved a degree of prominence — perhaps as a result of sponsoring Neoliberalism. I think of Neoliberalism as an ideology rather than a school of economic theories. So I should rephrase the title again as “How Ideologies Serve the Power Elite.”

I believe Phillip Mirowski captures the most complete and accurate depiction of Neoliberal Ideology. I also believe the C. Wright Mills and his successor G. William Domhoff have captured the essential structures of Political Power in their characterization of the Power Elite.

So — How do Ideology and Political Power interact? What is their dynamic? Altandmain pointed to a very troubling paragraph in the Michal Kalecki essay in yesterday’s comments. Looking at that essay once more I am troubled also by its conclusion. Kalecki concludes the potential for a rise of Fascism — as in the political/economic definition of the term — in 1943 America was slight and would be mitigated by the progressive politics in sway during those times. I would argue that the Ideology of Nazi Fascism achieved dominion over the existing Power Elites in Germany [as well as the business interests in the US who supplied money and expertize to the German Reich]. I also believe the Ideology of Soviet Communism achieved dominion over the Power Elites in Russia. In both cases Ideology drove the State toward horrendous actions I cannot reconcile as providing any service to a Power Elite.

The Power Elites of much of the world embrace and bolster the Ideologies of Neoliberalism using them as tools to consolidate their power and line their pockets. What is the chance Neoliberalism might cast off its leash and what kind of world might we see as a result?

Does the ascendance of an Ideology represent a cusp — a singularity — not well accounted for in the structural analysis of Political Power?

It’s really too bad that this article is written as though translated from another language by someone whose first language is not English. The punctuation is entirely random, with floating clauses and unnecessary commas. This makes for a difficult and unpleasant to reading experience.

“If You Look Behind Neoliberal Economists, You’ll Discover the Rich: How Economic Theories Serve Big Business”

Quelle surprise…..

Fukuyama’s claim about the end of history is quite comical. Hegel and others made similar claims, all of which are erroneous at the very least, or outright absurd. When our species is extinct and not before, our history will have ended.

I think it goes further than that. Liberalism and Neoliberalism attempt to turn society inside out, transforming the idea of “the market” from a useful tool for furthering society’s ends in appropriate situations into the overarching organising principle. Everything in markets.

…such is certainly the libertarian complaint…driven largely by libertarian think tanks and their enablers, Monbiot exposes:

“..Daniel Stedman Jones describes in Masters of the Universe “a kind of neoliberal international”: a transatlantic network of academics, businessmen, journalists and activists. The movement’s rich backers funded a series of thinktanks which would refine and promote the ideology. Among them were the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Centre for Policy Studies and the Adam Smith Institute.

(it is difficult to see any of the above as “liberal”, or sponsored by liberals; should possibly also consider IMF, World Bank)

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/15/neoliberalism-ideology-problem-george-monbiot

A book to add into the mix here is Nancy Maclean’s Democracy in Chains. It focuses on James Buchanan’s career….

… and his financial backers and their efforts to push their ideology as science in economics departments across the country.

This may also have to do with postwar prosperity stalling by 1960s!

See:

“thinking about the policy environment that made the turn to finance possible. And, in a nutshell, the argument of the book is that there were a number of discrete policy decisions that were quite influential in shaping this outcome, but those policies decisions were not made with the goal or objective of creating a financialized economy. They were really ad hoc, inadvertent responses to unresolved distributional conflict in US society as growth rates in the economy slowed. And one of the interesting things to me about the financial crisis of 2008-2009 is that those distributional dilemmas came right back to the surface. Financialization was not a resolution of these problems, but a displacement of them into the future. It was a kind of deferral.”

http://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1380&context=disclosure

Financialization and Social Theory: An Interview with Dr. Greta Krippner

See her paper also:

https://www.slideshare.net/conormccabe/greta-krippner-2005-the-financialization-of-the-american-economy

And video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N9X1hD1aGsQ

In Capitalizing on Crisis, Greta Krippner shows that the financialization of the U.S. economy was not a deliberate outcome sought by policymakers, but rather an inadvertent result of the state’s attempts to solve other problems. Krippner traces the ways in which policies conducive to financialization allowed the state to avoid a series of economic, social, and political dilemmas that confronted policymakers as postwar prosperity stalled beginning in the late 1960s.

Ah yes, stagflation. Blame it on the state, when it was really the private banks that drove it. This by pumping credit money into an economy that thanks to stagnation had crap all ways to make use of it.

If this was not about people’s lives and livelihoods we might be tempted to see this as just another Kuhn paradigm shift and analyze it dispassionately (as perhaps Friedman would).

But unlike physics this is about life and death and thus is a horrific example of how conceptual structures can be erected that, incidentally or intentionally, reorient our views and the world in bad bad ways.

The description of Hayek’s (and his disciples’) alliance with big business took me back to the early 80’s when, as a college student, I had an internship at a Westinghouse plant. The company encouraged us to watch videos featuring Milton Friedman, which they played in the cafeteria at lunch hour. I have very little memory of them, except one part that really stuck with me, which was Friedman’s explanation of why physicians should not be licensed by the State. He said something very close to “communities will figure out soon enough on their own who the good and bad doctors are.” An almost perfect statement of the rules as stated by Lambert.

Neo-liberalism bought back neo-classical economics that was last used in the 1920s.

It didn’t look at private debt then and it doesn’t look art it now.

They removed the 1930s regulations and 2008 was a repeat of 1929 in a different asset class, real estate instead of stocks.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

It’s obvious when looking at the debt-to-GDP ratio that monitors unproductive lending in the economy.

Blowing up the world with bad economics.

Japan would have seen what was coming if they had looked at unproductive lending in the economy.

They didn’t and it blew up in 1989.

“2008 – How did that happen?” the neoclasical economists.

It was obvious, if you looked at unproductive lending building in the economy:

(see graph above)

The neoclassical economists in the UK haven’t even realised the UK’s financial speculation and real estate economy is totally unsustainable.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.53.09.png

China would have seen the Minsky Moment developing if they had looked at unproductive lending in the economy.

They didn’t.

Canada, Australia, Norway and Sweden are being run with neocalssical economics, no one with any sense would let real estate bubbles like those develop.

How can we stop unproductive lending building up in the economy?

It’s easy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EC0G7pY4wRE&t=3s

Richard Werner was in Japan in 1989 and worked it out.

It’s bad economics that doesn’t look at private debt.

Austerity looks like a good answer when you are a neoclassical economist that doesn’t know what they are doing.

The IMF predicted Greek GDP would have recovered by 2015 with austerity.

By 2015 it was down 27% and still falling.

What did our neoclassical economists get wrong this time?

They weren’t looking at Greece’s private debt and the repayments on the debt built up on the boom. The IMF pushed Greece into debt deflation.

The neoclassical half-wits are still beating the austerity drum so let’s meet the man that explained things to the IMF, Richard Koo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Mark Blythe has looked at the empirical evidence from the Euro-zone.

In the Euro-zone austerity has been shown to damage the economies that undergo it and, the harsher the austerity, the worse it is.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B6vV8_uQmxs&feature=em-subs_digest-vrecs

Neoclassical economics is Mickey Mouse economics that doesn’t look at private debt making austerity seem like a sensible solution when it isn’t.