Lambert here: Richter argues that if the Fed unwound its balance sheet, that could drive up long-term yields, and unflatten the yield curve. But that moment of truth seems not to have yet arrived, if indeed it ever does arrive, or needs to arrive.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street.

Prices of US government bonds fell across the board on Friday, and their yields rose and set a number of nine-year highs, in some cases nine years to the day.

Many people have pointed at the Senate where the prospects of the tax cut are said to have “brightened” when the Senate approved a budget resolution. The tax cuts, if they make it, are said to lower government revenues by $1.5 trillion over 10 years. So maybe the bond market is starting to pay attention to government deficits and the national debt once again. But the bond market hasn’t paid attention in many, many years, and until the proof is in, I doubt it.

There are, however, other factors that predate Friday by many months. In fact, the moves in Treasury yields for maturities up to two years have been fairly consistent: yields have been surging.

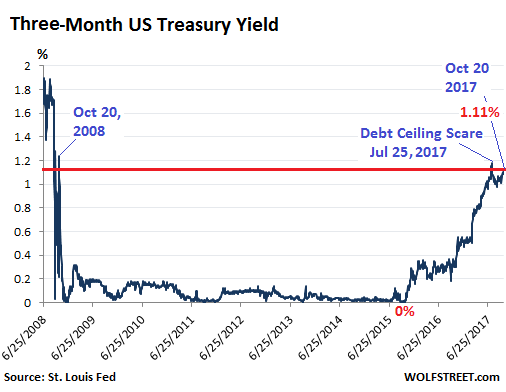

On Friday, the three-month Treasury yield rose to 1.11%, the highest since the brief spike around July 25, when the debt ceiling issue hit a speed bump. At the time the thinking was that in late September – when these securities would mature and the government would have to come up with the money to redeem them – the government might not be able to come up with enough money due to the debt ceiling. But this scare passed, the debt ceiling was extended temporarily, and the trajectory of the three-month yield returned to normal. Except for this spike, the three-month yield, at 1.11%, is now at the highest level since October 20, 2008 (let’s remember that date, it keeps cropping up):

In 2013 through 2015, the 3-month yield bounced around at near zero, and actually hit 0% several times in October 2015, which was the low point. In December 2015, the Fed raised its target range for the federal funds rate for the first time since July 2006. By now, it has raised the target range three more times, and it will likely raise it again in December.

The one-year US Treasury yield rose to 1.43% on Friday, the highest since October 29, 2008. It never quite got to zero but fell as low as 0.1% in 2011 and 2014:

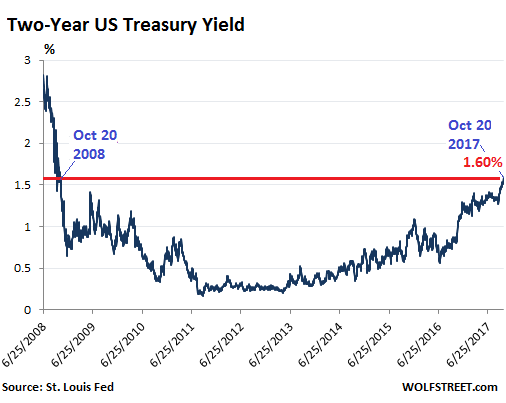

The two-year yield surged to 1.60% on Friday, the highest since October 20, 2008 – that date again. That was nine years ago to the day:

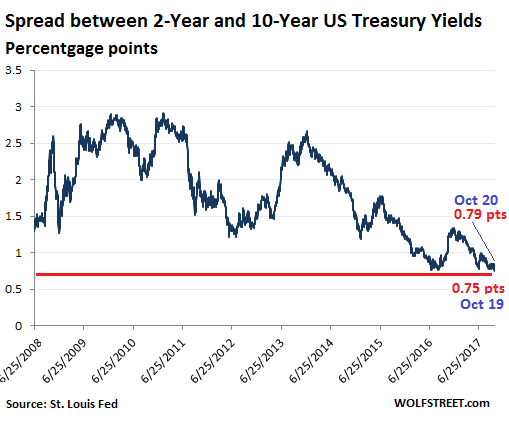

The two year yield is particularly significant in relationship to the 10-year yield: The difference between these two yields — the “spread” — has made its way onto the Fed announced worry list.

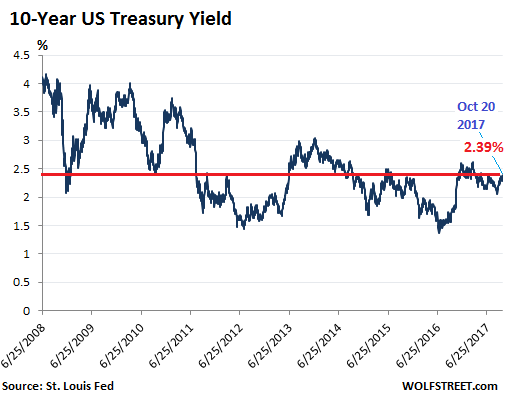

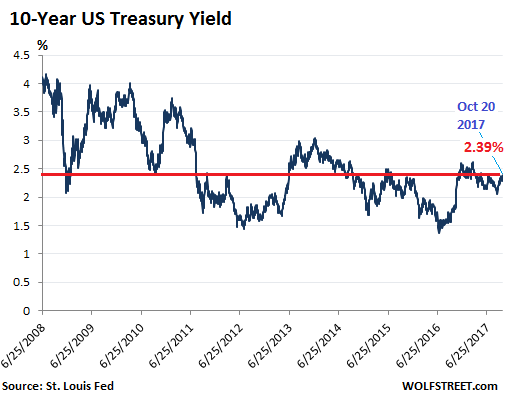

As the two year yield has surged since 2014, the 10-year yield has spent a lot of energy jumping up and then meandering lower, hitting 1.37% in August 2016, the lowest in the data series going back to the 1960s. The yield then spiked with the election, nearly doubling in a few months, reaching 2.62% in March this year, before swooning once again. But it has been rising recently and jumped 6 basis points on Friday to 2.39%:

This is where the Fed begins to worry: The spread between the two-year and the 10-year yields dropped to 0.75 percentage points on Thursday, the lowest since November 2007. At the time, the spread was widening after having been negative in late 2006 and early 2007 – due to the “inverted” yield curve – as the Financial Crisis was beginning to crack the banks.

On Friday, the spread widened to 0.79 percentage points, as the 10-year yield had risen more sharply than the two-year yield:

The negative spread between the two-year and the ten-year yield into the Financial Crisis still resides in the Fed’s collective memory banks. And they have put the collapsing spread onto their public worry list and have mentioned it in recent weeks. The Fed is concerned about the low long-term yields in the face of rising short-term yields. Generally, nothing good comes of this combination.

The fact that the ten-year yield isn’t moving properly in the same direction as the one-year and two-year yields should be one more reason for the Fed to pursue its QE unwind relentlessly. Unwinding its balance sheet that is loaded up with long-term securities would help drive up long-term yields. It would steepen the yield curve. And it would thereby pull the yield spread off the worry list. But for now, the numbers for that QE unwind are not lining up.

Curious things are happening on its balance sheet. Read… Is the Fed Getting Cold Feet about the QE Unwind?

People need to understand that the Fed and Treasury have currently agreed to redeem the maturing bonds by effecting an offset of Treasury cash, in effect erasing the cash and the bond’s principal.

My point is that the Fed and Treasury could instead effect the accounting offset before Treasury borrows these amounts, in effect erasing the public’s debt rather than continuing to borrow. Both are accounting offsets and equivalent in this regard. The erasure of cash serves the Fed’s goals of raising interest rates as the market now has to absorb the new Treasuries not being taken by the Fed, eliminates reserves in a SOMA-like transaction done by Treasury as they collect the cash from the open market (then the accounting offset erases it). Perhaps both this Fed and this Treasury also are happy to ensure that the dealer networks still have plenty of Treasuries to trade. So the public’s debt continues to increase so dealers are helped and Fed and Treasury staff are satisfied. Do not like these optics.

So one of the main points to observe is that the public agency debt held by the Fed can be redeemed via offset and this accounting offset can be applied to offset the need for new borrowing, meaning that the public’s debt is actually $4 plus Trillion less, if they would only agree to do it this way.

Perhaps bond traders on the long end understand this could happen. As Yellin’s remarks from yesterday indicate, they are still learning how to use their huge book of holdings.

I ask then what is in the public’s interest? At the very least they could make some speeches telling the public that they could erase their debt holdings and that the public’s debt is not large at all, though they intend to regulate these markets and protect the fiscal affairs of the public’s government using these holdings, in the public’s interests (not in the traders’ interests or the staffs’).

The market knows the fed plans to unwind so the 2-10 spread will not expand by the fed doing this. If it accelerated the program beyond expectations thenlong end could dip even more because the market would two-step the implications i.e. Rates spike too quickly and then stem economic growth hence 30 year treasuries are buys and yields go down..

If the Fed stopped taking new issues at an even higher rate than current plan why would you expect the long end to dip even more? With more being sold buyers should demand a higher yield, not a lower yield.

And on Oct 20 the ten year market took a step jump up, modest, and I guess yesterday that sounded down a bit, but markets don’t step jump on their own, this was a reflection of Fed stuff, perhaps even because the redemption plan was happening.

The Fed intends to go slowly and watch what happens. But I think their concern is not about rates dropping, they are concerned about tantrums and mischief by the bond market trading infrastructure, and the credit channels affecting the rest of society with increasing prices under cover of all this. Do we want these to step jumps in spirals upward, like the 1970s, no.

If the Treasury does not send cash to the Fed to redeem maturing bonds, the money supply shrinks and the demand for Treasury bonds is reduced. If the Treasury remits cash, only the demand for Treasury bonds is reduced and the question is: will market demand increase? However it is accomplished, eliminating the Fed’s QE bond holdings portends higher rates across the yield curve. The potential for higher rates is already evident at the short end of the curve while the long end continues to be suppressed. The net effect is to continue to suppress cap rates for hard and paper capital assets with the larger effect being to paper capital assets. The stock market operates as a general barometer of economic health in our economy. Higher interest rates will makes the purchase of hard capital assets that will be used to increase or modernize production will aid longer term economic growth while lower stock prices will delay increased employment. Overall, I see the economy as being more able to absorb a cash for maturing bonds than any other scenario that has the effect of reducing the circulating money supply.

Great article, great charts until the final paragraph:

This is decidedly a minority view. The Fed has been tightening the overnight rate (all that it actually controls) for nigh on two years now. As Wolf Richter points out, long-term rates instead of rising as usual, remained flat.

To most analysts, this screams ‘policy error.’ Long-term Treasuries are factoring in deflation risk from excessive tightening (with price and wage inflation still low) leading to possible recession.

More quantitative tightening will only exacerbate the yield curve’s tilting toward inversion, and Bubble III’s eventual demise. This is the Andrew Mellon, hair-shirt school of central planning at work. Purge the rot!

Legitimate question (though perhaps a stupid one, forgiveness please if so): why wouldn’t the QE unwind help raise long term rates? The Fed has been one of the biggest buyers of long maturity bonds recently and much of QE is/was made up of long term bonds. If the Fed starts to unwind then it means one of the largest buyers of long-bonds will slowly fade away to nothing. If one of the biggest buyers of something cease to be, shouldn’t the prices of said something go down (due to less demand), which in the case of bonds means their yields go up?

Unless there is some complex backlash or whatever I have trouble imagining any other result, could you help me understand?

The Fed has exchanged redemption amounts for new issues. As it tapers in doing this, more bonds go to the real public auction. So more supply should mean that buyers ask for more yield.

Based on my direct exchange with very senior Fed officials, I can assure you, this is precisely what they expect. The public when borrowing will as a result need to pay more interest. Just go thru search engines and look at the last five days trading on ten year bonds, there was a conspicuous step jump on Oct 20.

Think what might ensue when the Fed plan reaches its run rate in less than a year – $50 billion in public agency debt is redeemed monthly via offset of Treasury cash holdings so the bond markets will have to absorb $50 Billion a month more than current Treasury borrowing plans.

This should raise the cost of public borrowing, directly seen in the Treasury issues and in a spiral upward reaction in the credit channels (all borrowing affected then).

But the redemption plan has never been done before at these magnitudes, so we will see if the market reacts in shock and does weird stuff.

The Fed’s current policy strikes me as a way of ensuring yield curve compression. The principal will no longer be used to repurchase a new issue, once the old issue matures. Every bond that matures next month, whether it originally issued 29+ years ago as a 30 or 9+ years ago as a 10, is still today a very short term instrument. So the short end of the curve should go down in value, up in yield, as short term rates should clearly go up. But I have trouble understanding why the value of the last issued 30 year bond, and bonds that are not about to mature, should change dramatically.

I second this question. Someone please elucidate this point.

I took a quick look at the EU govt/countries bonds reports, just for comparison’s sake. Reason I looked is because for the past 10 years US T’s have been the flight to safety buy ,no matter the interest rate paid, for much of the EU and others, imo. I didn’t gain any insights by checking the EU countries current bond rates. I do wonder how much T rates are set in consideration of geopolitical situations and in coordination (unspoken) with other central banks, in an effort at some sort of larger stabilization.

What’s the incentive for anybody to buy UST @ a meaningless interest rate, aside from a flight to ‘safety’?

I think that’s pretty much it, flight to safety.

If you’re a bank, the nominal interest rate the Fed pays is still better than nothing so the ever growing ocean of surplus reserves ends up in treasuries to get whatever little drip there is of free money.

Of course as the A**hats in DC do their thing, “safety” takes on scare quotes.

Oh yes, there’s also the mercantilist impulse: if your an exporting country and you want to hold onto your market share in the US you buy Treasuries to finance the sale of your exports. Which impulse continues to be enforced by WTO and IMF on those the US dominates and indulged by Germany, China and India to import jobs (to themselves) by exporting demand (to US).

Well, if you live in a high income tax state (CA/NY) the “meaningless interest rate” can be substantial, if you’re stashing million$ for “safety”. (T-Bills aren’t state taxable.)

Housing loans key off the ten year bond. Housing demand already down, just half what it was in 2006, granted that was too string, but pop nearly 10% higher now.

So housing will decline, autos too.

Economy and employment much weaker than stats indicate, plus lending falling hard.

But Feds think economy strong enough to support higher rates…

As usual, Feds are advancing recession. But this time there is record margin debt to unwind, plus corps can’t afford borrowing more to buy their stocks at high rates. Lots of forced selling… and smart money like Buffett already out, some primed to go short… what’s left are weak hands…

Yawwwwwwwwwwwwnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnnn

How does this impact the REAL economy of REAL ASSETS fella?

Banks borrow short and lend long. Inverted yield curves are bad for profits because the borrowing costs more and lending brings in less.

There is another concern for the Fed, which is what an inverted yield curve implies. It suggests that the Fed will be cutting interest rates soon, which would most likely be caused by a downturn in the economy.