By Davide Cantoni, Professor of Economic History at the University of Munich, Jeremiah Dittmar, Professor of Economics, London School of Economics, and Noam Yuchtman, Associate Professor, Haas School of Business, UC-Berkeley. Originally published at VoxEU

Five hundred years ago today, Martin Luther posted 95 theses on the Wittenberg Castle church door critiquing Catholic Church corruption, setting off the Protestant Reformation. This column argues that the Reformation not only transformed Western Europe’s religious landscape, but also led to an immediate and large secularisation of Europe’s political economy.

On 31 October 1517, 500 years ago today, Martin Luther posted 95 theses on the Wittenberg Castle church door critiquing Catholic Church corruption, setting off the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation marked a critical juncture in Western history – the moment when the religious monopoly of the enormously rich and powerful Catholic Church was successfully challenged.

Social scientists have long argued that the Reformation transformed the European economy and played a role in the rise of the Western world. Yet these views have been contested, and empirical evidence on the economic consequences of one of the most important episodes in European history has been mixed (e.g. Weber 1904/1905, Tawney 1926, Becker and Woessmann 2009, Cantoni 2015, Rubin 2017).

In new research, we document a first-order consequence of the Reformation: an immediate and large secularisation of Europe’s political economy (Cantoni et al. 2017). We gather rich evidence from early modern Germany and show that:

- Human capital and fixed investment shifted sharply from religious to secular purposes after 1517, and disproportionately so in regions that adopted Protestantism.

- The growth of economic activity in the ascendant secular sector specifically reflected the interests of empowered secular territorial rulers, and came at the expense of religious elites – the hiring of lawyers rather than theologians, the building of palaces and castles rather than churches.

Conceptual Framework

This consequence is surprising. How did an intensely religious movement, preaching biblical revival, produce economic secularisation? And why did resources so disproportionately shift towards the control of secular rulers? To help us understand how the introduction of religious competition during the Reformation could transform Europe’s political economy, we develop a conceptual framework.

Prior work has generally considered churches as producers of salvation, and believers as consumers (e.g. Ekelund et al. 2006). Believers pay a price, comprising financial costs in the form of tithes and donations and time spent attending masses and praying. Viewed through this lens, entry by a competitor into a hitherto monopolistic market will reduce prices in the market for salvation, leaving believers (as consumers of religion) better off. Indeed, Protestant theology offered a path to salvation that did not require the purchase of indulgences to fund expensive monasteries or a massive bureaucracy of priests.

But in addition to the ‘market for salvation’, we argue that understanding the economy-wide effects of the introduction of religious competition requires consideration of a second market – one in which secular authorities pay a price to religious elites in exchange for political legitimacy, in the form of a church’s endorsement of a ruler. The bargains in this market are at the heart of political economy across history, wherever religion provides legitimacy to political elites (Weber 1978, North et al. 2009, Chaney 2013, Rubin 2017).

The price paid by the secular lord for the church’s endorsement is typically the lord’s own endorsement of the church’s theology, as well as some set of temporal concessions: money, land, economic privileges, and political power. The ability to bargain with two providers of religiously derived political legitimacy will allow secular rulers to strike a better deal with either entrant or incumbent.

At the centre of much of the post-Reformation bargaining between secular rulers and religious elites was the massive wealth that had been held by monasteries that were closed after 1517, particularly in the Protestant territories. When the Reformation broke out, monasteries were in many territories the largest landowners in Germany, often owning as much as a third of total agricultural land. Would this wealth be reallocated to church purposes, or would it be expropriated by secular lords? Our model suggests the latter, due to the shift in the balance of power toward secular rulers.

A Changed Political Economy in Early Modern Germany

Rich historical evidence confirms that secular territorial lords bargained with Protestant religious elites over the allocation of monastic resources. While Protestant theologians initially attempted to reserve these resources for religious and social purposes, the price of political legitimacy fell, and secular territorial lords were able to strike deals that left them significantly wealthier.

Protestant rulers expropriated considerable monastic wealth. In Hesse, Landgrave Philipp received annual revenues of 16,500 guilders in 1532 from monastery lands and 25,000 guilders in 1565, equivalent to one-seventh of total state revenues and around 1,000 person-years of skilled wages. Overall, 40% of monastic wealth in Hesse went to the ruler – not to religious, educational, or social welfare purposes. In East Frisia, Count Enno II converted the monastery in Norden into a summer residence for himself and converted the monastery at Ihlow into a residence for his brother. In Brandenburg, monasteries were allowed to keep their privileges following the adoption of Protestantism in exchange for a payment of 300,000 guilders. Protestant theologians provided the legal justification for these transfers of wealth – this is consistent with our framework, which views these transfers as outcomes of bargains between secular and religious elites.

Empirical Evidence on Resource Reallocation

The massive shift in political power and resources after 1517 should have had broader consequences for the allocation of resources across the economy:

- We expect a reduction in labour demand in the religious sector of the economy, and increased demand in the secular sector – particularly from enriched secular lords.

- Forward-looking students would have shifted their educational investments away from theology, which paid off specifically in the religious sector, and towards more general subjects.

- Major new construction events – embodying physical, financial, and human capital, as well as land – would have shifted toward structures reflecting the interests of secular lords (palaces and administrative buildings).

To examine whether resources shifted in the direction suggested by our conceptual framework – away from church uses and toward secular uses, especially those favoured by empowered and enriched territorial lords – we collect a wide array of micro data shedding light on the German economy of the 16th century.

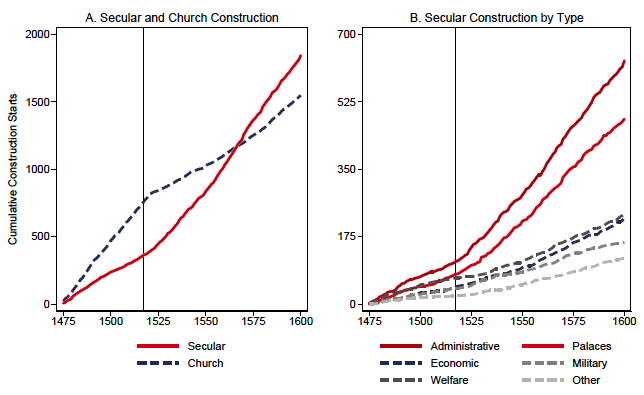

First, we analyse major construction events in towns and cities across Germany. As we show in Figure 1, during the Reformation new construction events shifted from primarily religious purposes toward secular ones. We see a striking pivot from church-sector construction to secular-sector construction precisely at the time of the Reformation, as shown in Panel A. Consistent with our conceptual framework, within the category of secular construction, there was a sharp pivot precisely toward the uses favoured by empowered secular lords – the construction of palaces and administrative buildings increases after 1517, as shown in Panel B.

Figure 1

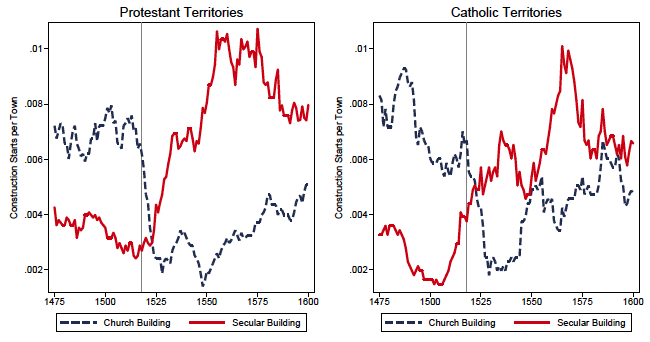

These changes were particularly evident in the Protestant territories of the Empire. Figure 2 shows that both Catholic and Protestant regions witnessed a decline in church construction following 1517. However, only in Protestant regions (left panel) was there a sustained increase in secular construction, leading to a permanent gap between church and secular construction rates. In our analysis, we also show that the additional secular construction in Protestant territories was, for the most part, composed of palaces and administrative buildings.

Figure 2

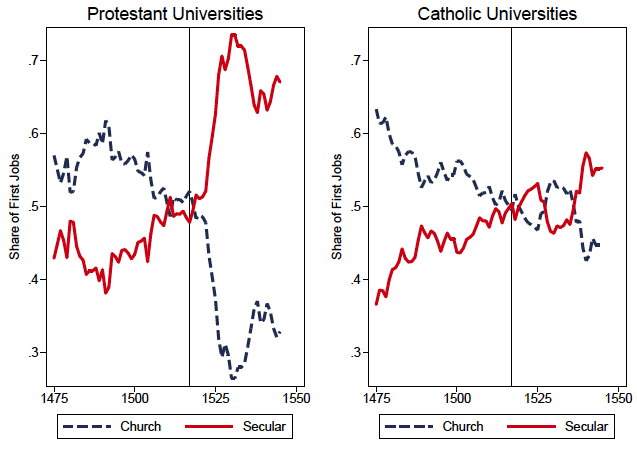

Turning to occupational choices, in Figure 3 we show careers of recipients of academic degrees from German universities through the year 1550. Prior to 1517, graduates of eventually Protestant universities sorted into religious and secular occupations at similar rates to graduates from universities that would remain Catholic. After 1517, however, there is a sharp shift towards ‘secular’ occupations among Protestant university graduates, and no such shift among Catholic university graduates. The Protestant shift toward secular occupations was concentrated in the administrative sector that reflected the interests of secular rulers.

Figure 3

The shift in occupational sorting across sectors is reflected in human capital investments as well. Students at Protestant universities shifted sharply away from theology study, towards other degrees such as law and arts, after the Reformation.

Implications for Social Science and Beyond

Our findings shed new light on some of the most important debates in the social sciences. We provide evidence that the Reformation indeed marked a decisive economic break from the past, playing a causal role in the transformation of Europe’s economy. While this may appear supportive of the ‘Weber Hypothesis’, we provide a mechanism for long-run effects of the Reformation very different from the cultural channel emphasised by Weber (1904/05). The finely grained data we collect enable us to document that Protestant and Catholic regions and universities were not on different trajectories before the Reformation. However, our analysis indicates that the initial separation between religious and secular authority in Europe provided a fundamental precondition that shaped how the introduction of religious competition impacted the economy.

Five hundred years on from Martin Luther’s audacious act, our findings confirm that the Reformation transformed not only Western Europe’s religious landscape, but also its politics and economy. Thus, social scientists have been right to point to the Reformation as a crucial turning point in European and world history. Significantly, our findings indicate that some of the Reformation’s most important consequences were unintended, and have not been fully documented before – the results of interactions among religion, politics, and economics, which produced a secular Europe from its most famous religious movement.

See original post for references

Money did a funny thing right around 1517, in that it was the first time coins ever had a date of issuance on them. Previously they would have a portrait of the emperor, ruler, etc on them, which is how you ascertain what year an antique coin is from.

Gold coins in circulation started expanding widely all across Europe as galleons brought back all that glitters, and a sense of wealth must have permeated throughout the continent, as there was no paper money yet to muddle things financially.

I think Graeber discusses this in Debt: The first 5,000 years. History has gone through several periods in which coined money rose then receded in importance. Coined money was more important during times of mass warfare, since coins arose as a way of paying armies. Pocket-sized tribute that could be distributed to individual soldiers. If I remember right it was also associated with slavery. Similarly, when coined money rose in importance, credit became less so. We’re currently in a credit-upswing with a down-swing in gold and slaves.

There’s a yawning gap in issuance of gold coins in Europe-with the exception of the Byzantine Empire, for about 800 years after the fall of the western Roman Empire. And also the designs of base metal coins everywhere turned more into 7th rate efforts from an artistic standpoint, they didn’t call it the Dark Ages for nothing.

The design of coins blooms as the reformation proceeds, into little works of art, equaling and surpassing what the Greeks were able to do in 400 BC, in terms of beauty.

Roman soldiers were paid in denarii, and as it declined in buying value due to hyperinflation against aurei, so did the army’s performance on the field.

Mercenaries tend to be cash on the barrelhead types, this was called a ‘blood thaler’ as it was what Hessians were paid with for their services to King George II in the Revolutionary War:

https://www.numisbids.com/sales/hosted/fischer/155/thumb00621.jpg

I find this interesting as I’ve recently been reading up on Italian Renaissance architecture, specifically the classic Italian rural villa. One reason traditionally given by historians to the economic and cultural riches of the period is that the power of the Papal States prevented a landed aristocracy from monopolising power and so dissapating wealth on grand chateaux and castles (as generally occurred in the north). Instead, an urban merchant class thrived with its roots in the countryside surrounding the new city states. This newly wealthy class invested in more modest country retreats, which became the classic Italian villa, to contrast with their more functional city homes. So the influence of the Catholic church wasn’t uniform throughout Christendom – closer to home (Rome) it was quite positive, providing an environment for culture and trade, just becoming more extractive and reactionary further away from the centre.

Martin Luther, unlike his American Civil Rights namesake, turned on the peasants when they were no longer useful to him, and became a threat to his newly minted upper class bourgeois sponsors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Against_the_Murderous,_Thieving_Hordes_of_Peasants

Perhaps, with the dawn of capitalism and the bourgeois also came the neo-liberal, with Martin Luther the titular Adam.

“”The people must always be kept in poverty in order that they may remain obedient.” — Calvin

Please provide a link or citation for this quote. Thank you.

Citation

https://www.google.com/search?tbm=bks&q=%22The+people+must+always+be+kept+in+poverty+in+order+that+they+may+remain+obedient.%22

See first link that comes up. Otherwise, all the search on internet refer back to djrichard making same comment many times on other sites. Let’s see if this comment disappears down the rabbit hole with no rhyme or reason.

This is more regarding usury, but also touches on the peasant revolt.

From: https://www.amazon.com/Lost-Science-Money-Mythology-Story/dp/1930748035 [apologies to the link to Amazon]

On usury, Luther went through three periods. First he condemned anyone who charged interest as: “A thief, robber and murderer … Money is an unfruitful commodity which I cannot sell in such a way as to entitle me to a profit. . . . In its effort to make a certainty out of what is uncertain, will not usury soon be the ruin of the world?”

Next, from 1523-25 Luther was somewhat reconciled to usury after being frightened by peasant revolts and their preacher leaders such as Dr. Jacob Strauss of Eisenach. These populists used the Mosaic Law of the Bible to threaten the concept of private property. Luther and Melanchton condemned any popular initiatives in this matter, Luther claiming that reform had to originate with Princes, and Melanchton declaring that the Law of Christ was not to be taken as the basis for the organization of secular society.

Then after a 15-year silence on usury, in the midst of a severe usury/ economic crisis in 1539, Luther again blasted the userers, starting with the Princes. Martin Bucer (1491-1551) became a kind of bridge between Luther and Calvin on the usury question. He preached that the Old Testament prohibition only forbade “biting” usury – “neshec” – meaning poison snake bite.

Unfortunately Martin Luther was not aware of the advanced usury concepts developed by the Scholastics: “Luther tore the whole of this beautiful fabric to the ground, and carried back the teaching on usury to the primitive bare prohibition of all gain on loans, with the inevitable result that it could not be lived up to in the facts of modern life, and that it consequently fell into disrepute,” wrote George O’Brien.

I was surprised the article didn’t mention usury, so thanks djrichard for giving good information in his post.

I would add that the Reformation spurred the building of additional universities, especially in Scotland and the Dutch Republic.

What I would love to see is a a study on the environmental destruction wrought by the wars of religion. All the trees felled not just for the Spanish Armada, but to make charcoal to fire for steel arms. All the arms in the Dutch Revolt, the French wars of religion, the 30 years war.

And what were the public health consequences of the St Bartholmew’s massacre? If you dump hundreds of bodies into a river, what happens to the people who live down river?

I have been searching, for so far, have found no materials on this.

Sounds like an interesting research subject. The tree counts (CO2) you describe should be straight-forward to derive. A visit to a Renaissance Fair blacksmith should provide enough information, along with strength-of-forces tallies, to ballpark the numbers. Just watch out for rennies in leather corsets!

Nothing compared to the Industrial Revolution where all of England’s forests were leveled to produce charcoal for iron and steel smelting, and when forest for became difficult to find, Coal Mining became the replacement.

You won´t find anything like that because most of what is said about the Spanish Armada is just invented. Most of the ships where not brand new; they gathered from different kingdoms of Spain (including Portugal), and around 3/4 of the ships managed to get back. The only thing that is true about the hole story is that the enterprise was a complete fiasco caused by men and Nature.

About the Reformation and Luther the key factor is the invention of the printing press some years before, which granted almost anyone direct access to read Scriptures in the local language, and to write and propagate anything, even fake news. Just like today with the Internet by the way.

While Martin Luther is the catalyst for such things, the most extreme example is probably that of Henry VII of England, where the creation of the Anglican Church remade the economy of the country, and is one of the reasons that it became a world power.

Wasn’t that Henry VIII?

D’oh!!!!!

Interesting. Since a response to Max Weber’s ideas is implicit here, let’s not forget how Luther and his secular supporters were disposed toward the demands of the peasantry for economic justice, which tells a decidedly different side of the story. Or rather a continuation of the same. A lively discussion of this here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zqExjUhcNjA

Catholics liked to expropriate wealth, too, though. See Templars and Jesuits.

Also, I believe universities in Italy were secular from the get-go, run by students and faculty and emphasizing law and medicine, whereas in France they were associated with Church and State and focussed on theology. Not that main currents of above post may not be correct.

Also both Protestantism and Catholicism considered secular government to be ordained by God and dissent / lèse majesté to be akin to blasphemy/treason, punishable by death preceded by hideous torture. Our recent notions of secularism and human rights are quite novel.

Coincidentally watched a travel show on PBS yesterday evening which focused on art, architecture, religious and military history, Luther, and key secular rulers of major cities in Northern Germany from the 1600’s onward. This post ties into and adds much to the depth of my understanding of that content. Thank you for this insightful article and the thoughtful comments here by other readers.

I have been curious about the roots of the “Protestant work ethic” and how that and related values play into Germany’s economy and the dominant ideology of key European institutions today. This piece invites further exploration of a possible historical thread.

probably more than you want, but this 30 min video gives a good over view of Luther’s view of work

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y_klCLA3-24

Thanks, dc. I’ll take some time to watch it.

https://twitter.com/consent_factory/status/925353683067555840

On a more serious note, I think CJ Hopkins (who tweeted the above) would argue that that which supplanted the church after the reformation in a sense became the church itself. At least that’s the sense I get from reading his work, in particular: https://consentfactory.org/2017/10/20/tomorrow-belongs-to-the-corporatocracy/ He talks in terms of the how the neoliberal status quo defends itself by stigmatizing (as pathologically beyond the pale) anything that could be construed as an insurgent threat to the “hegemony of global capitalism”. But from what I can tell, it’s really no different than what the chuch did in its glory days. Somebody calls you a witch today, no big deal. But woe be to ye if you’re outed today as not normal by the neo-liberal center. When they call you a russian dupe or stooge, well then you might as well be a witch as far as the media is concerned.

Perhaps instead of the expression “L’Estat? C’est Moi” the expression should be “L’Eglise? C’est Moi”. It would explain a lot of what we’re seeing in the media in terms of who’s “fallen” and the media showing the pathway back to salvation and redemption.

Not mentioned was the chummy relationship between the Church of Rome and remaining Catholic monarchs. For example, visit any Spanish castle and see pics of the Pope and the Monarch arm in arm – visit any cathedral to see Cardinali crowning the monarch – each gave the other legitimacy to rule over a) souls (tything), and b) everything else (taxes). Let us not forget that the Church of England was really the king moving his franchise from Rome to Canterbury in order to consolidate more wealth and power in London (as a bonus, it pissed off the Catholic French).

Finally, there is the eerie contemporary manifestation we see in warring factions of Islam. Islam runs both the spiritual and secular in Iran, and Erdogan is increasingly using Islam to expand his franchise in the Middle East – as if NATO did not have enough on its plate already.

The Reformation was as much a product as a cause of secularization. These trends had been developing since well before Martin Luther was born (cf. Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce) and accelerated after him. Church laws against charging interest, appropriation and then poor development of massive amounts of land, capricious measures against private property, stultifying attitudes towards science and rational thought (faith over fact) and endemic corruption had been pissing off the emerging classes of merchants, technical innovators and capitalists for a long time.

I was struck by the same thought, when viewing the charts above, the Reformation seems to have been an acceleration of trends which continued at the preexisting pace in those areas that remain Catholic.

A positive feedback loop generated by and ultimately causing the breakdown of the instability of a monopoly, in this case a religious one.

“then poor development of massive amounts of land, capricious measures against private property, stultifying attitudes towards science and rational thought (faith over fact)”

The subjugation of morality and community to avarice and profit. Oh yes, we’ve now got so much stuff, but so little else. Is the orthodoxy of science and wealth any less cruel than the churches of old, and how has it wounded our planet. Progress indeed!

The climax of efficiency, also in Germany, the systematic murder of the surplus population. What a trajectory, indeed?

for what it is worth the originator of the secret Swiss bank account was Huldrych Zwingli to protect refugees. That is why Zurich is the financial center of Switzerland.

the real contribution of Protestantism to economic development occurs at the grammer school level rather than university. The emphasis on scripture translated into an emphasis on the importance of education for all, or at least a lot more, so that every child, even girls, could read the scriptures. Both Luther and Knox pushed for universal childhood education, they lost that fight, but they did succeed in extending education for more children, even girls.

++ Yes. Lots of good info. in these comments.

I guess this post must thumbnail some much more substantial body of new evidence and thought which very greatly extends the evidence it presents supporting the conclusions it arrives at — such as they are.

I feel extremely uncomfortable with Sociology in the hands of Neoclassical or Neoliberal economists and a fellow traveler of some sort from a School of Business. I think a small extract from near the top of this post illuminates the reasons for my discomfort:

“churches as producers of salvation, and believers as consumers …. Viewed through this lens, entry by a competitor into a hitherto monopolistic market will reduce prices in the market for salvation, leaving believers (as consumers of religion) better off” …

However I can understand how Neoclassical or Neoliberal economists and a Business School professor might have difficulty with concepts like ethics and religious belief which served the sociological analyses by previous less “Market”-aware sociologists.

I actually thought the article was some sort of joke or parody, but I’m so uninformed about how religion is viewed from an economic perspective that I didn’t want to say anything. Glad I’m not the only with reservations (even if mine are completely wrong).

I agree with your reservations. I think this economic analysis is weak even as an economic analysis and I didn’t notice that it contributed anything to the existing analyses of the Reformation. I’m even reluctant to call it an analysis. I wish this were a joke. The sort of Neoliberal analysis of everything in terms of the Market is very troubling. I’ve been playing with a fuzzy notion that Power Elites adopt, cultivate and use an Ideology to extend and maintain their control over a society — but every so often an Ideology takes control over the Power Elite. I think that might be one way to think about Nazi Germany or Stalinist USSR where Ideology drove actions no sane Power Elite would even ponder as a means for extracting wealth or exerting control.

If our Neoliberal Overlords really truly believe the Market is an all powerful information processor capable of knowing more than any human could ever know — the inferences from and corollaries to that belief are truly appalling. This post would suggest some “economists” truly believe people choose a religious faith based on rational choices in a Faith Market. Isn’t faith something you believe without proof or by making a rational choice? Was any agnostic ever tilted toward faith by Pascal’s Wager except on their deathbed?

The sentence after the one you quote says

I’m no Protestant Reformation maven but don’t these sentences exactly reverse cause and effect? It wasn’t “entry by a competitor into a hitherto monopolistic market” that “reduce[d] prices in the market for salvation”—it was that the fact that Protestant theology “did not require the purchase of indulgences,” etc. that, in effect, allowed (or at least helped) it to compete. Is that way off base?

It would be hard to reverse cause and effect in a case where no cause and effect was established to reverse. The selling of indulgences were but one of many of practices of the Catholic Church Martin Luther contested and though probably one of the most crass I doubt it were a difference crucial to bringing about the Protestant Reformation. Why worry the logic in an analysis like this post that lacks much logic to worry over?

One of the main reasons there was such a growth in the sale of indulgences prior to the Reformation is that indulgences, unlike such famous abuses as simony and pluralism, were extremely popular.

Slightly off-topic but the surprise for me is the public’s disinclination to adopt quantum reality as a replacement for God. I take it as read that religion explains luck – be good and you are rewarded, be bad and you are punished.

Quantum mechanics shows randomness governs at the sub-atomic level. The same circumstances will have different outcomes, i.e. luck arises from quantum randomness.

> Prior work has generally considered churches as producers of salvation, and believers as consumers

Something tells me these prior workers never ran these premises by a theologian or a cleric.

Maybe there’s more to their definition of “secular” than meets the eye, but this puzzles me:

Seems like a bit of a false dichotomy. How is a divine right monarch not a religious elite? Yes, I know, a king is a political figure, and in that sense, secular. But cuis regio, eius religio, amirite? And of of course history shows that whose religion, their gold.

“How did an intensely religious movement, preaching biblical revival, produce economic secularisation?” By ignoring that your “secular” elites are also religious. And really, how religious was a church rife with simony, the sale of dispensations, an utterly corrupt clergy, and 92 other offenses? The surprise comes from assuming more of a divide than I think obtains. The authors’ “secular” was part religious and their “religious,” part secular. Or as Wikipedia has it, “By 1548, political disagreements overlapped with religious issues, making any kind of agreement seem remote.[6]” IMNSHO, these kinds of divides, like the infamous “mind-brain problem” in psychology, are made too absolute, and then we puzzle over how they could possibly influence each other.

So let’s see what’s different between their pre-test and post-test. In the old dispensation, you needed to stand in the proper relation to a proper priest of the proper dogma of the one and only proper church in order to obtain salvation. Evidence of salvation came in the form of participation in the exclusive rites of the Catholic church.

In the new, you still needed all that, only now (after a period of wars — were they secular, because led by monarchs, or religious?) the monarch could select Old Church or New Church for you, and in the new, evidence of salvation came from the new mechanism of grace, one with which anyone could form a personal relationship: the Market. God shows his favor only on the deserving, you know, as I’m sure Her Royal Clinton would agree.

Anyway, looks to me like the money followed the religion.

For “could form a relationship” I should say, must. Before, you were outside by reason of original sin, and could only get back in through the good offices of the Church. But the Church and the Nobles owed you some concrete material benefits.

Now, your salvation was up to you, ultimately. And so were your fortunes. I do see in this erosion of social cohesion. Atomisation. Each person, was now free to conduct direct bilateral negotiations with God/The Market.

In the new dominant dispensation, the same as today’s dominant dispensation: If you’re poor, not only do you suck at engaging the Market, but God hates you, too, and you might even be in league with the devil. We’d best be sure by making your life a living hell.

You “could” keep your old religion, if you were satisfied, And you could effectively self-excommunicate, keep what you could carry, and GTFO, too, with the help of your friendly neighborhood mob in making up your mind.

Your choice. Markets = Freedom!

(Now I’m thinking the pain in my elbow tonight is from painting with such a broad brush here. I’ll get my coat. ;)

Sorry. I’m congenitally depraved. Who, exactly, is it I have to pay to stay alive?

What is it, ideology determines social order, or social order determines ideology? Ideology rationalizes power relationships but does not determine them. Martin Luther would have remained an itinerant monk or fuel for a bon fire if the German aristocrats had not latched onto his religion to rationalize their power. Notice how the new “religion” handled peasant revolts and heresies about private property. What counts here logically consistent ideology or raw power? Was it religious dogma or the new technology of gun powder?

Likewise today’s orthodoxies, market fundamentalism, scientific materialism. They rationalize the power of those that control the Federal Reserve printing presses. Again any challenge to private property no matter how logically consistent the ideology, are ruthlessly suppressed with police power. Notice in Wisconsin the only unions that kept their collective bargaining rights were the police unions. So much for logical consistency.

I ran into the “religious” equivalent of this sort of Market thinking in one branch of the Protestant Church of the Life Abundant. The little religious group that tried to draw me in took the meaning of the life abundant to mean a life of abundant wealth and goods in return for “faith”. — Come to think of it a fair amount of religion — particularly the early religions involved making bribes to the gods in return for favors in life. That does get very economic — perhaps a worthwhile place to apply the Wisdom of the Market and test its Knowledge powers. If only Neoliberalism had been available to help the Aztecs build a better Market for keeping the Sun moving. Maybe Cortez and the Catholic Faith conquered the Aztecs by offering a competitor with a much better price point for keeping the Sun moving along the calendar — although there were some gotcha’s in the fine print.

Hello? Somebody hasn’t been paying attention. The religious and secular elites have been co-joined since the beginning of civilization. Their uneasy alliance is fueled by the realization that they are better off collaborating than competing in their primary activity: coercing labor from the masses to provide wealth for the elites.

They take turns achieving temporary ascendancy over the other, but these things always swing back (they need each other, you see). At the time of the Reformation, the Church had been in the ascendancy for many centuries. The secular elites were ordered about by the church. You go on crusade .. or else, etc. Emperors approached Popes on their needs, did penance, etc. The Protestant reformation weaken the grip of the Catholic Church, allowing the secular elites to squirm out from under the church’s foot. This happens time and time again. The Protestants, by the way, were no more tolerant than the Catholics, they both were tyrannical (Obey or be punished).

Consider the Russian Orthodox Church. The Russian Revolution broke the grip of the church on Russian Royalty and was banished so it could not get a grip on the new government. But the USSR is no more and the Russian Orthodox Church is back, albeit cowed and licking Putin’s boots, but is on the ascendancy again. Who is to say what their future looks like?