Lambert here: “Political economy”! Quelle horreur! Readers may find this article an interesting entry point to discussing the “neo-feudalism” construct (whose accuracy and utility is not clear to me, at least).

By Alex Klein, Senior Lecturer in Economics, University of Kent, and Sheilagh Ogilvie, Professor of Economic History, University of Cambridge. Originally published at VoxEU.

A famous hypothesis posits that serfdom was caused by factor endowments, specifically high land-labour ratios. Historical evidence seems to refute this idea, but with substantial identification problems. This column uses microdata for more than 11,000 Bohemian villages in the year 1757 to control for other potential influences on serfdom. The results support the factor endowments hypothesis, with higher land-labour ratios intensifying serfdom, suggesting that institutions are partially shaped by economic fundamentals.

Institutions are widely viewed as a fundamental cause of economic performance. But what are the causes of institutions? We don’t have a definitive answer (Acemoglu et al. 2005, Ogilvie 2007, Ogilvie and Carus 2014). But since institutions often have roots far in the past, looking at historical institutions provides a way to tackle the question.

Labour-coercion institutions – serfdom and slavery – have profoundly affected many economies through the centuries. Serfdom obliged rural people to do forced labour for landlords, who also regulated their mobility, demographic behaviour, and market participation. Serfdom prevailed in most European economies from roughly 800 AD onwards, weakening between 1300 and 1500 in the west of the continent but surviving and intensifying in most of the centre and east. This development is known as the ‘second serfdom’ (Klein 2014, Ogilvie 2014a). In many serf economies, a large percentage of rural families had to perform forced labour. Since the rural economy produced 80-90% of pre-industrial GDP, serfdom affected the majority of economic activity. Labour coercion under serfdom reduced labour productivity, human capital investment, innovation, and living standards, so much so that its varying intensity is widely regarded as a major determinant of divergent European economic performance between 1350 and 1864 (Broadberry and Gupta 2006, Dennison 2011, Ogilvie and Carus 2014, Klein 2014, Ogilvie 2014b, Baten et al. 2014, Markevich and Zhuravskaya 2017).

Theories of Serfdom

What caused serfdom to be stronger in some places and weaker in others? One famous theory was put forward by Domar (1970), who hypothesised that serfdom was a response to factor endowments – specifically, high land-labour ratios. In economies where wages were high because labour was scarce relative to land, Domar argued, landowners devised institutions such as serfdom to ensure they could get labour to work their land at a lower cost than would be the case in a non-coerced labour market.

This hypothesis seems to fall foul of the facts. Postan (1937, 1966) and North and Thomas (1973) argued that, on the contrary, rising land-labour ratios after the Black Death in 1350 made serfdom decline by increasing outside options for peasants in vacant rural holdings and urban workshops. Brenner (1976) rejected all claims that factor proportions affected serfdom, pointing out that rises in the land-labour ratio after 1350 coincided with the decline of serfdom in Western Europe and its intensification in the east. Subsequent scholarship argued that country-specific variables such as class struggle, state power, and the overall institutional framework were decisive – although a different story was told for each society (Aston and Philpin 1988, Hatcher and Bailey 2001).

Acemoglu and Wolitzky (2011) breathed new life into Domar’s idea by providing a theoretical framework explaining why factor endowments might affect labour coercion differently in different contexts. A rise in the land-labour ratio, they argued, could have two countervailing effects. It might increase the price of the output produced by the landlord, which would increase the productivity of labour coercion, and thus increase the quantity of coercion, along the lines hypothesised by Domar. But greater labour scarcity might also increase the wage that serfs could earn in outside activities, for instance in the urban sector, which would decrease the productivity of labour coercion, and thus decrease the quantity of coercion, as argued by Postan and North. The relative size of these two effects will vary with market demand for landlords’ goods and wages for serfs outside the coerced sector. So the same rise in land-labour ratios can result in different coercion outcomes in different societies.

What Happened in Bohemia?

This new framework is clear and powerful, but needs to be investigated empirically. To do this, we collected extraordinarily detailed micro-level data on 11,670 serf villages, covering the entirety of 18th century Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic (Klein and Ogilvie 2017). We calculate how much coerced labour serfs had to do, both human-only and in human-animal teams. We then measure the economic fundamentals faced by serfs and lords – land-labour ratios for different types of land, village sizes, outside options in different categories of town, geographical location, types of lord, fragmentation of lordship, and many other variables.

We use a multiple regression framework that controls for other influences on labour coercion, enabling us to identify the effect of factor proportions in a way that qualitative studies could not. By analysing a specific society, we also control for political-economy variables – class struggle, state power, the overall institutional framework – which may have obscured the impact of factor proportions in previous studies.

Unearthing the Domar Effect

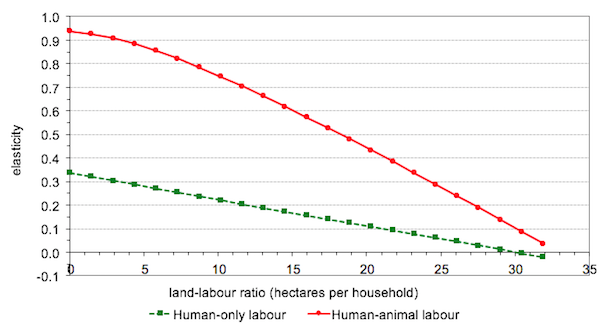

We find that where the land-labour ratio was higher, labour coercion was significantly higher, and thus that the Domar effect outweighed any countervailing outside options effect. Figure 1 graphs the elasticity of labour coercion with respect to the land-labour ratio according to our regression models, setting all other regressors at their sample mean values.

Figure 1 Elasticity of coerced labour in Bohemia with respect to the land-labour ratio, 1757 (two-part regressions)

For human-only coerced labour, the elasticity with respect to the land-labour ratio is non-trivial, lying in the 0.20-0.34 range, for the three-quarters of villages where the land-labour ratio is below 12 hectares per household. For human-animal coerced labour, the elasticities are three times as big. They lie between 0.5 and 1.0 for the 92% of villages where the land-labour ratio is below 17 hectares per household and are still non-trivial, lying in the 0.2-0.5 range, for the remaining villages.

Why did the land-labour ratio affect human-animal more than human-only coerced labour? We think the Domar effect was bigger for human-animal labour and that the outside options effect was smaller. The Domar effect was intensified by complementarities between human and animal labour, and the usefulness of animals in transporting grain to manorial breweries, wood to manorial glassworks, and ore to manorial ironworks (Klein 2014). The outside options effect was reduced by lack of demand for animal labour in alternative uses, such as urban crafts and commerce, which required human dexterity, communication, and calculation more than brute force. Animals were also harder to hide than humans, so landlords could detect their illicit use more readily, further reducing outside options for human-animal labour teams.

Why did labour coercion respond less to the land-labour ratio as the latter increased? It happened, we think, because of technical constraints on coercion. In villages with very high land-labour ratios, serfs needed most of their labour just to keep themselves alive. Lords could not extract it without killing the serfs. When labour became extremely scarce, that is, market pressures broke through and no coercion technology could resist them. Bohemian landlords recognised these constraints themselves, granting temporary freedom from coerced labour in drastically depopulated villages after the Thirty Years War (Cerman 1996, Štefanová 1999, Zeitlhofer 2014).

Feeble Outside Options

How did outside options in the urban sector affect labour coercion? A striking result from our regressions is that the urban potential available to a serf village – the size and proximity of urban markets – had almost no statistically or economically significant effect on labour coercion in the village. The only urban effects that were statistically (and in one case economically) significant were positive – that is, they increased labour coercion – suggesting towns created greater opportunities for lords than serfs. This is not surprising, since historical evidence shows Bohemian towns doing things that stifled rather than increased serfs’ outside options, specifically by restricting rural crafts and trades that competed with those practised by town citizens (Cerman 1996, Ogilvie 2001, Klein and Ogilvie 2016). But most urban effects on labour coercion were so small as to have no economic significance.

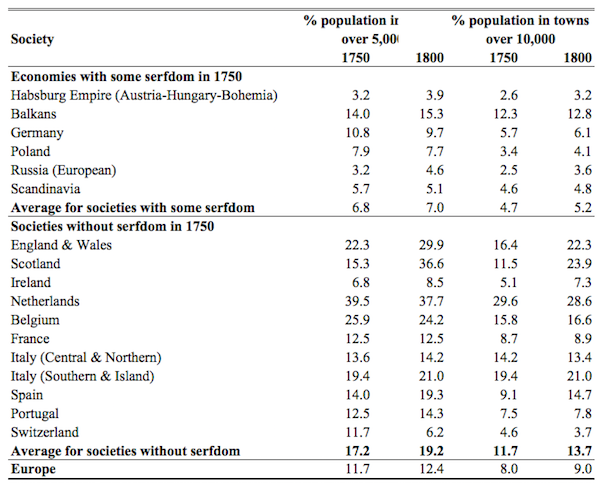

This is consistent with the weakness of towns in Bohemia, as in most parts of eastern-central Europe. As Table 1 shows, in European societies where serfdom still survived in 1750, just 7% of the population lived in towns over 5,000 inhabitants, compared to 17-19% in societies without serfdom. In the Habsburg Empire, which included Bohemia, just 3-4% of people lived in towns over 5,000 inhabitants. In serf societies, towns were too few and weak to increase wages for serfs or prices for landlords. They provided no serious outside options for either party, so they exercised no serious effect on serfdom.

Table 1 Urbanization in European Societies, 1750 and 1800

Note: Average for societies with and without serfdom in 1750 is calculated on the basis of total population.

Source: Calculated from Malanima (2010), pp. 260-2.

Factor Endowments Shape Institutions

Our study holds constant political-economy variables by analysing a specific society, and controls for other influences on serfdom. This enables us to provide, for the first time, clear evidence that the net effect of higher land-labour ratios was indeed to increase labour coercion. The positive impact intensified when landlords extracted labour in human-animal teams, and diminished as land-labour ratios rose; both patterns consistent with technical limits on coercion. Towns in Bohemia, and in most European societies where serfdom survived in the 18th century, were usually too feeble to provide outside options to either serfs or landlords, and thus did not alleviate coercion – if anything, they sometimes slightly intensified it. So Domar was right – factor endowments can significantly influence serfdom. Institutions, our study shows, are partly shaped by economic fundamentals.

Err. As the article says, Habsburg Empire at the time consisted of Austria, Bohemia and Hungary (and also Silesia, but that was mostly lost to Prussia in 1748 IIRC). These three counties were extremely different in terms of urbanization, population density, production etc. etc. Which makes the last table a bit of pointless – as Hungary in 18th century had more in common with Poland (demographically) than with Bohemia – which was even at that time becoming more industrialised than Austria proper (and in late 19th and early 20th century Bohemia was much more industrialised than Austria)

I have some doubts about some other claims of the study (as in for example how they controlled for political economy – the result of 30 year wars was profound in Bohemia, the region that suffered from it most economically and politically; the consideration of ease-of-trade on whether the towns were operating closed or open markets etc. ) , but I’d have to look at the study, for which I have no time at the moment..

Fascinating. Part of my mother’s family came from Bohemia in the 19th century. Bohemia and Moravia had special political/religious conditions because of the earlier Reformation, because of the Hussite revolution. This was suppressed during the 30 Years War. In addition, the landlords were not only Catholic (vs Hussite) but German (vs Czech). Autocratic control and political conservatism was the order of the day in such repressive conditions. My ancestors (wheat farmers) left Bohemia because of the military draft, because of the Catholic church tithe and because my great-grandfather was told by the Emperor’s men, that since there was a shortage of bakers in Bohemia, he had to be a baker, not a farmer. A rather paternalistic system, not unlike the Czar’s POV in neighboring Russia.

I’m a Bohemian’s Bohemian also, and the Catholicism was so despised, that upon nationhood status a century ago, most Czechs decided that dogma & others won’t hunt. Perhaps the least religious country in the world.

To what extent, if any, was 18th century Bohemia involved in external grain trade? It’s been argued that the growth in Eastern European grain exports during the early modern period provided an additional incentive for landlords to tighten controls over the rural labor force.

Very little. The main exports (by value) in 18th century Bohemia were linen and crystal glass IIRC. Bohemia is not really a country to raise grain in..

I put a comment here but it looks like it dissapeared, but I have some issues with the study – but I’m not going to redo my post.

Thanks for the nuance. I really get into stuff like that.

Unless it’s the comment that begins “Err,” it’s nowhere to be found. Sorry. Skynet moves in mysterious ways.

“Coercion technologies”?

Translating into English: in thinly populated rural areas the landlords owned the land and the peasants became serfs or starved. In urban areas there were more options for the poor to survive. In the Reconstruction south many blacks became sharecropper serfs due to the lack of land. But they also had the option of moving to northern cities and many did. Perhaps the “coercion” relates to freedom of movement as well as class mobility. In any event isn’t the above article just stating the obvious?

I’m not familiar with Bohemian serfdom and how it operated, but in Brandenburg/Prussia and Russia the key “coercion technology” (terrible term, BTW) was the beginning of state assistance in hunting down runaway serfs and returning them to their lords. In the case of Brandenburg the date most frequently cited for this policy is 1653. In the case of Russia, it’s 1649. These “Fugitive Serf Laws” were part of what made the system work. The nobility got its government-guaranteed forced labor, while the rulers gained the nobles’ acquiescence in the building of royal absolutism.

> the beginning of state assistance in hunting down runaway serfs and returning them to their lords.

I wonder if they had a Second Amendment-equivalent

The “Err” posts captures the gist of it, so I won’t mind :)

Yeah, funny how economists can spend all this time researching what should be abundantly clear. This question cracked me up –

How about a guy with a gun who wants to be in charge of said institution so they can lord it over everybody else?

“Freedom of movement” by farm laborers was actively suppressed in the American South. The usual way to do this was through debt-peonage, with the workers paid in plantation scrip — useless for purchases off the plantation. While organizing the Poor People’s Campaign and March on Washington in 1967 Martin Luther King found workers in Coahoma County Mississippi, who had never seen cash money, only scrip.

After the great flood of 1927 the black population of Greenville, Mississippi, including the college-educated professional classes, was kept on the levees at gunpoint for months as forced labor to re-build the levees, while the white population was allowed to leave in paddle boats (some with the band playing “Bye-bye, Blackbird.”)

The Chicago Defender, a black-owned newspaper which urged agricultural workers to come to Chicago, was forbidden, or had to be read aloud in back rooms at night, in secret. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How it Changed America, by John M Barry (2007) tells this story in great detail and is a fantastic book, if you don’t know it already.

The need to keep black workers “on the farm” lessened considerably beginning in the 1940s with the mechanization of cotton farming, giving rise to what was arguably greatest internal migration in history as five million workers fled the farms. The fact that virtually no money was spent by the Federal Government in helping these millions of impoverished refugees is a big factor in the the racial problems we have been having since them. The Promised Land: The Great Black Migration and How It Changed America (1991) by Nicholas Lemann tells this story. I won’t even mention the huge and very profitable (to the states) deep South system of prison (David M. Oshinsky, Worse Than Slavery Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice, 1997 http://www.historyisaweapon.com/defcon1/oshinsky.html).

And yet quite a few African Americans did make it to the north. My point was not meant to apply to all blacks. Obviously the definition of “serf” is that you are in some kind of bondage.

Those are really great sources. There’s so much good scholarship going on it’s hard to keep track of it. Same with science. Bright beacons in the fog and gloom!

The Southern white elites also used guns, in cases actual artillery, and hangings, to terrorize, kill, the population, and sometimes drive away any leaders. This included not only the black population but also fair size white one as well that supported them. It also included armed coups in some cities and states if the anti-segregationists won.

Often it was straight up gun battles, in which the anti segregationists sometimes won, but they lost the war. This continued into the 20th century. If you want to see some egregious examples of terrorism ostensibly for white supremacy, but really had economic reasons also, you can look the then race riots, especially of Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1921. One of the wealthiest black communities in the country was obliterated (including the first bombing by air in the the country!) hundreds kill, probable mass graves, and a coverup. Further support for segregation was partially economic not racial was the fact that when the Great Migration began, many Southern plantation and business owners tried to stop. They went so far as to send people to train and bus stations to stop blacks from leaving. Reminiscent of the Antebellum South.

So I have no problem believing armed suppression, or enserfment, especially as in the then South, the economy was a poor agrarian economy and which share-cropping effectively is, and under which many whites too were enserfed.

The economics encouraged it but the system was created and enforced by violence.

We forget that freedmen comprised approximately 10% of the Union Army after Emancipation; that implies not only experience with weapons, but an officer class accustomed to command. No doubt it was a principal object of the formerly slave-owning class to decapitate them, which they apparently did. I need to understand “Reconstruction” a lot better than I do.

Just about every major war up to Vietnam had blacks fight to join, have most whites say they would do badly, and then most people would say that they did great especially the ones who fought with them. From the American Revolution to Korea. Every. Single. Time. I think it’s efforts like the Dunning School that erases that history. Also of poor whites, Indians, Mexicans(Who had lived for centuries in the Southwest). It’s all been white washed and sanitized with the Approved Story so please do not blame yourself for any lack of knowledge.

IIRC, only less than 100 blacks were commissioned officers by the end of war, highest one being a lieutenant colonel I believe (non-combat troops though, he was a head of hospital). There was a good number of the non-coms. Tthe usual organization had (after a while) commissioned white officers, and black non-coms. I can’t remember off the top of my head whether there was any black officer who would have white soldiers serving below him, but I don’t think so.

I’m not sure whether the 10% in the wikipedia are really all combat troops, as a very large number of blacks were employed in what would be euphemistically called “support troops” (cooks, labourers etc.). It is sort of funny (not), that the racism displayed by most North troops to arm freedmen was overcome only when some officers pointed to them that a black soldier will stop a bullet just as well as a white one will, and it thus means that “many a good white boy will make it back home”.

Even sadder though is the treatment the Confederates gave to the captured black soldiers. The wikipedia article linked mentions it briefly, but doesn’t really give it justice. For one, the PoW exchange breakdown, when Confederation refused to exchange black soldiers (and Union consequently refused to exchange anyone if blacks were excluded) was the reason behind the massive PoW deaths on both sides (the prisoner camps weren’t set as long-term facilities), especially in Confederacy which had problems feeding its troops, not to mention PoWs. The atrocities on black soldiers would now be war crimes of first order. (mind, you, there were atrocities on slaves by Union soldiers that were quietly ignored and don’t tend to make it to the history books).

And yes, Reconstruction is a fascinating subject.. As a random tidbit, I keep saying “well, if you want to raise a monument to a heroic Confederate general, why not Longstreet?”* – and the answer is, because he turned anti-slavery and Republican post war (of conviction).

*) well, he has, small ones, but not nearly as prominent as the other “proper” Confederates.

To this reader, the concept and practice of serfdom are disturbing. I would be interested in recommended reading to find out more about the points of view of the lords, i.e., those who controlled serfs in whatever manner. Is there some literature that touches on such themes?

What introspection was there, how did they rationalize any lordliness with whatever religious or spiritual considerations may have influenced them, and so on?

How did one decide to be a lord, besides being born into the position or fighting one’s way in?

I only have a slight understanding of European serfdom, especially the re-enserfment, but I can bloviate on America and more modern times. A common theme in supporting American slavery, and latter Jim Crow, was the inherent, almost bestial nation of blacks, and to a lesser degree of poor whites. Giving “those people” anything like equal rights would destroy society, threaten the women, and so on. Some supporters of slavery even claimed it was a positive good as it allowed a refined educated leisure class that could peruse the finer things in life like philosophy.

When slavery was abolished it was recreated using share cropping, and prison labor, using not only the recently free blacks, but also the “white trash.” So, it was supposedly criminality, not slavery that was causing their enslavement. Victim blaming. Blacks have always gotten the worse treatment in American history especially as they were generally legally property, not even human, but right next to them are Indians, and a large white underclass. (Vomitous isn’t?)

You see similar feelings, and thoughts, just not as well articulated or openly spoken, on the poorer American classes today. I think what ever the original ideology was supposed to be, Neo-liberalism, including the belief in the Anglo-American version of Meritocracy, has been changed into a modern version of Social Darwinism; along with added elements of Francis Galton’s eugenics, and the Europeans’ inherent (created maybe, certainly enabled) racism that was used to support 19th and early 20th century Free Market Capitalist colonialism, the new improved version of neo-liberalism supports late 20th and current 21st neo-colonialism that now is world wide including America.

As we see from the life expectancy figures differentiated by income, neoliberalism has created an environment where theft, fraud, extortion, and exploitation are literally adaptive behavior. Social Darwinism at its finest.