By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently working on a book about textile artisans.

While snorkelling a couple of years ago near the Indonesian island of Flores, I was ensorcelled by a magnificent coral reef. Just under the water loomed another magical world teeming with vividly-coloured sea creatures.

Although being underwater had always terrified me, that world was so captivating that over the next year, I learned to scuba dive, so that I could explore it further.

Recently, global warming has severely stressed many of the world’s coral reefs– via a phenomenon known as coral bleaching. When sea temperatures rise, corals expel the symbiotic algae– zooxanthellae– that live in their tissues, and the coral itself turns a ghostly white. During the last two years, the Great Barrier Reef has been worst affected, according to the Guardian, with more than two-thirds of it now damaged. Recent forecasts suggest that the southern part of the reef is also now at risk, according to another Guardian report, making the prospects of recovery of this natural wonder of the world unlikely.

At a larger level, the health of the world’s coral reefs is another indicator of the state of planet, and that is bleak.

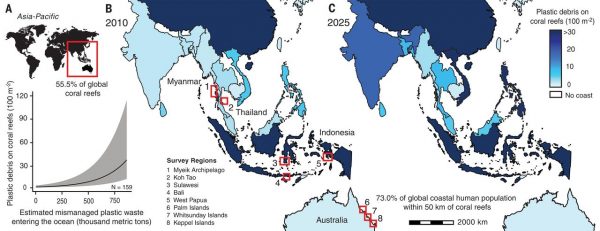

But bleaching is only one threat that coral reefs face. A study reported this week in Science, Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs, chronicles another rising threat to reefs: plastics. Dr. Joleah Lamb and ten other researches– herein after Lamb et al.– surveyed 159 coral reefs in the Asia-Pacific region and found that billions of plastic items were entangled in the reefs. Damage was worst in those reefs with spikey coral species, as their spikes were more likely to snag plastic. Once a reef was draped in plastic, disease likelihood increased 20-fold. The scientists noted that plastic debris stresses coral by depriving it of light, allowing the release of toxins, and thus providing pathogens with a foothold for invasion.

Figure 1: Estimated Plastic Debris Levels on Coral Reefs

Source: Lamb et al., Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs.

The Study

Reefs are not only worth preserving for their beauty alone. The Lamb study notes that they provide US $375 million in goods and services annually through fisheries, tourism, and coastal protection. These benefits and the reefs themselves are threatened by the estimated 4.8 million to 12.7 million metric tons of plastic waste enter the ocean in a single year. The resulting influence on disease susceptibility in the marine environment was before this study unknown.

Lamb et al.:

surveyed 159 coral reefs spanning eight latitudinal regions from four countries in the Asia-Pacific for plastic waste and evaluated the influence of plastic on diseases that affect keystone reef-building corals ((benthic area = 12,840 m2) (Fig. 1). The Asia-Pacific region contains 55.5% of global coral reefs and encompasses 73.0% of the global human population residing within 50 km of a coast. Overall, we documented benthic plastic waste (defined as an item with a diameter >50 mm) on one-third of the coral reefs surveyed, amounting to 2.0 to 10.9 plastic items per 100 m2 of reef area [95% confidence interval (CI), n = 8 survey regions]. The number of plastic items observed on each reef varied markedly among countries, from maxima in Indonesia [25.6 items per 100 ± 12.2 m2 (here and elsewhere, the number after the ± symbol denotes SEM)] to minima in Australia (0.4 items per 100 ± 0.3 m2) [citations and some figures omitted].

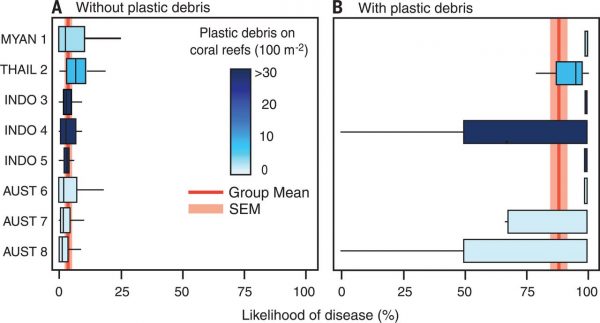

Although terrestrially derived pollutants have previously been implicated in several disease outbreaks in the world’s oceans, the researches noted that no studies have yet examined the influence of plastic waste on disease risk in a marine organism. In this study, they visually examined 124,884 reef-building corals for signs of tissue loss characteristic of active disease lesions and found “found plastic debris on 17 genera from eight families of reef-forming corals.”

Figure 2: Plastic waste influences disease susceptibility of reef-building corals

Source: Lamb et al., Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs.

I will spare readers here the intervening steps in which Lamb et build their argument— although the work is accessible, and the key points summarized in five paragraphs in the article linked to above. Some of these look rather dense, and I didn’t want to bury readers in detail and risk that some wouldn’t persevere to the conclusions.

While I encourage interested readers to read the full account, for those others who prefer to jump straight to the point in what is, after all, a weekend read, here’s the conclusion:

Our study shows that plastic debris increases the susceptibility of reef-building corals to disease. Plastics are a previously unreported correlate of disease in the marine environment. Although the mechanisms remain to be investigated, the influence of plastic debris on disease development may differ among the three main global diseases that we observed. For example, plastic debris can cause physical injury and abrasion to coral tissues by facilitating invasion of pathogens or by exhausting resources for immune system function during wound-healing processes . Experimental studies show that artificially inflicted wounds to corals are followed by the establishment of the ciliated protozoan Halofolliculina corallasia, the causative agent of skeletal eroding band disease. Plastic debris could also directly introduce resident and foreign pathogens or may indirectly alter beneficial microbial symbionts. Cross-ocean bacterial colonization of polyvinylchloride (PVC) is dominated by Rhodobacterales, a group of potentially opportunistic pathogens associated with outbreaks of several coral diseases (. Additionally, recent studies have shown that experimental shading and low-light microenvironments can lead to anoxic conditions favoring the formation of polymicrobial mats characteristic of black band disease

By disproportionately reducing the composition or abundance of structurally complex reef-building coral species through disease, widespread distribution of plastic waste may have negative consequences for biodiversity and people. For example, on coral reefs, the loss of structural habitat availability for reef organisms has been shown to reduce fishery productivity by a factor of 3. [citations omitted.]

What Must Be Done

By 2025, if present trends continue, the researchers note that the plastic waste entering the oceans from land is predicted to increase by one order of magnitude from present levels. This accelerating scourge will only further stress already-fragile coral reefs.

So, what must be done?

Climate-related disease outbreaks have already affected coral reefs globally and are projected to increase in frequency and severity as ocean temperatures rise. With more than 275 million people relying on coral reefs for food, coastal protection, tourism income, and cultural importance , moderating disease outbreak risks in the ocean will be vital for improving both human and ecosystem health. Our study indicates that decreasing the levels of plastic debris entering the ocean by improving waste management infrastructure is critical for reducing the amount of debris on coral reefs and the associated risk of disease and structural damage [citations omitted].

This BBC account, A third of coral reefs ‘entangled with plastic’, quotes the principal author of the study on necessary action:

“Plastic is one of the biggest threats in the ocean at the moment, I would say, apart from climate change,” said Dr Joleah Lamb of Cornell University in Ithaca, US.

“It’s sad how many pieces of plastic there are in the coral reefs …if we can start targeting those big polluters of plastic, hopefully we can start reducing the amount that is going on to these reefs.”

Last week, I posted on the EU’s much ballyhooed, long-awaited sadly-lacking European Strategy for Plastics in a Circular Economy, which, unfortunately, relies unduly on recycling rather than upfront elimination to reduce plastics waste and even within this narrow framework, endorsed all too feeble goals (see EU Makes Limited Move on Plastics: Too Little, Too Late?). The Lamb et al. study marshals concrete evidence as to the damage being wrought by plastics ion coral reefs– a further clarion for steps to be taken to confront this urgent global crisis.

Is anyone listening?

Maybe if we tweaked headlines and perspective/point of view on these articles- viz:

Human’s Plastic is sickening (fill in the blank).

Somehow we seem to perceive ourselves as not a part of the closed system that is the earth, whereas we are the prime actor, the source and cause of the manifold issues that threaten our very existence.

By properly framing things–not to be a source of despair– but to engage a bit of Free Willy and effect the change we need to effect. Realize the Potential.

Happy to share some sunday morning metaphydics mumbo jumbo…

Wonderful post. The maps makes sense given this: ” In a recent report, Ocean Conservancy claims that China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam are spewing out as much as 60 percent of the plastic waste that enters the world’s seas.” PRI’s report is excellent–and the horrific photos give a graphic sense of how big a problem garbage is in Asia.

https://www.pri.org/stories/2016-01-13/5-countries-dump-more-plastic-oceans-rest-world-combined

Yup, plastics in the oceans are a problem. I would like to know specifically how most ocean plastic ends up there. Is it people who throw it in the ocean? Is it plastic going overboard while we were shipping it to China for recycling? Does it magically escape en route to landfills? Since like I have said before there is no chance of banning plastic outright limiting plastic ocean exposure will depend largely on determining how it ends up there in the first place and what steps we can take to minimize that.

Note to self, read the other comments before you open your fat mouth. Hana M’s link answers my question. Setting up proper trash collection in Asia would practically eliminate this problem.

toss plastic in landfill. landfill floods. plastic floats to surface and runs downstream. stream flows to ocean. ocean fills up. throw more plastic in landfill and repeat.

All I have is speculation but I’d be shocked if that had anything more than the most trivial effect and could be solved with better landfill selection criteria. Most plastics do fine in landfills. https://fighttheplasticbagban.files.wordpress.com/2014/03/plastic-bags-in-landfill-not-a-problem.pdf

A significant amount goes overboard from ships, too, both in their trash and when containers break loose.

I lived on the beach in Oregon for 10 years; it’s quite astonishing what washes up. Once the entire beach was lined with light-bulb sized commercial flash bulbs. Plastic wasn’t a huge component, but that was 40 years ago.

Oregon was where all the bath toy ducks kept washing up for years and years after an accident at sea. This story from CNN quotes Curt Ebbesmeyer an oceanographer who’s been tracking them.

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/10/09/business/goods-lost-at-sea/index.html

Container shipping accidents definitely contribute, though likely not as much as the Asian garbage

Add to this the recent discovery of plastic contaminated table salt and one has to wonder when disease begins to appear in humans.

And not just through the consumption of table salt but from the fish we eat.

All ocean fish “breathe” this same plastic infused salt water.

I hope there are studies being done on this.

Is there anyway to remove plastic from the ocean. I know it’s better to not have it there but since it is…

You’d think some organism would adapt to eat plastics in the ocean; which probably will happen, since evolution hasn’t had long to work on the problem. Of course, if the organism gets into fresh water, big “grey goo”-type problem….

Another source of plastic pollution in China are sheets of polypropylene used as an agricultural mulch. It is particularly valued in arid regions because it prevent water evaporation.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-09-05/plastic-film-covering-12-of-china-s-farmland-contaminates-soil

The same Bloomberg article notes “Scientists in Spain may have an another answer: wax worms. Larvae of the wax moth Galleria mellonella are able to biodegrade polyethylene, researchers at the Institute of Biomedicine and Biotechnology of Cantabria showed in a study published in April.”