Economists have not been as vocal in the climate change debate as one might expect. That seems surprising given their eagerness to weigh in on topics like marital relations, which was once seen as outside their purview. Whether the world needs to curb growth in order to mitigate climate change would seem to be a centrally important issue for economists to consider, yet it has gotten at best passing interest. As we’ll discuss today, a 2016 paper by Servaas Storm and Goher-Ur-Rehman Mir, which has not gotten the attention it warrants, suggests that complacency is ill-advised.

Both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the Conference of Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in Paris, commonly referred to as the Paris Agreement, focused on national targets that are ambitious: that of reducing carbon emissions by 50% by 2050. Many advanced economies have been patting themselves on the back for moderating their carbon emissions and relying more on “green” energy sources. However, these countries consider themselves to be responsible only for the carbon they produce, not the carbon they consume. As Storm and Mir explain, that difference is crucial.

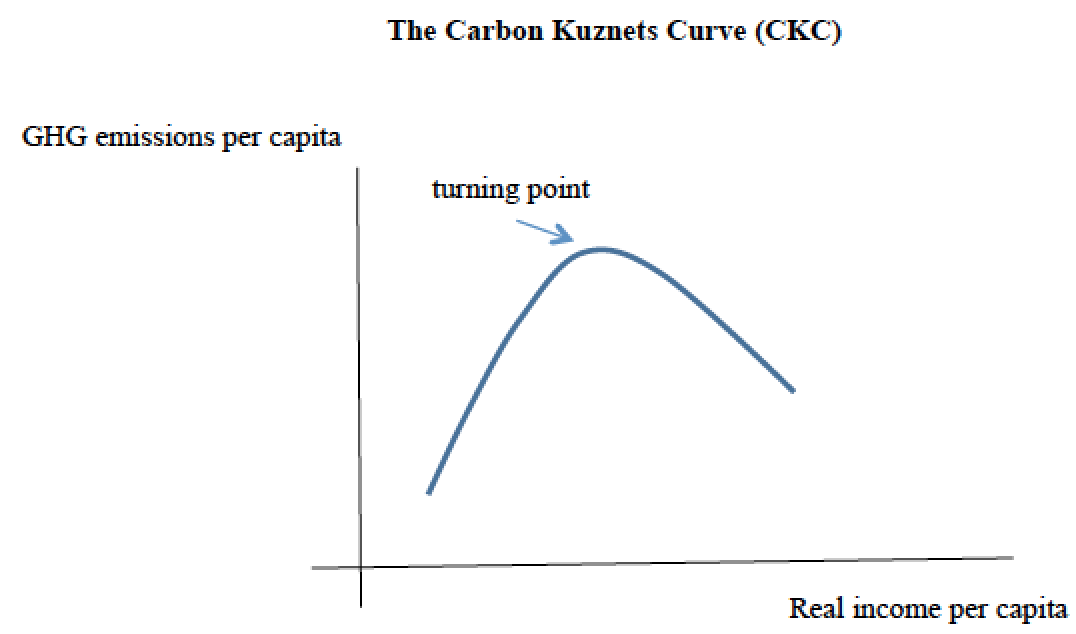

As we’ll discuss, economists’ faith in a model that has only weak empirical support (the Carbon Kuznets Curve), the choice not to hold countries responsible for trade in setting their emissions targets, and the reluctance of policymakers to admit that fighting climate change probably means accepting lower growth, have all supported making only modest responses to the threat of climate change even as temperatures are coming in at or just off record highs. The data in recent years are in line with the grimmer end of the range of climate change forecasts. And it’s hard not to notice the freakishly warm weather: I was just in Alabama, where it hit an unheard of 80 degrees in February, and the flowering trees are in bloom more than a month early.

When debate about climate change started to get serious, as a result of the release of the first set of reports from the International Panel on Climate Change in 2007, the fact that the devastating effects didn’t appear to kick in until late in the 21st century bizarrely allowed economists to ignore them.

As most readers know, financial economics is based on net present value models, where you take future benefits or costs and discount them back to the present by an assumed interest rate. Anyone who has run financial models will tell you that results beyond 30 years (in more normal interest rate environments, more like 15 years) have pretty much no impact.

Nicolas Stern, who wrote the Stern Review, argued for urgent action on climate change, had to assume a discount rate of 0.5% in order to make the damage done by climate change roughly 100 years out to matter in economic terms. The use of what was deemed at the time to be a ridiculously low discount rate allowed many to dismiss Stern as having had to cook the numbers in a big way to make his case for Doing Something Now. Mind you, Stern was not calling for hairshirt remedies. He estimated that the investment needed to lower the amount of carbon emissions as 1% of global GDP per annum, but action needed to be taken soon, particularly regarding investments made by power generation players.

I don’t recall anyone pointing out subsequently that the move in the decade following to super-low interest rates, and for one quarter of the advanced economies, negative policy rates, made Stern’s discount rate seem not crazy, particularly since the early years in any financial model have disproportionate impact on results. Separately, the bigger issue is that the use of a NPV model was wrongheaded. That presupposes that climate change should be treated in “return on investment” terms: we spend now, in terms of incurring costs to lower our carbon footprint, in order to have the payoff later of less climate change-related damage.

But in fact the more appropriate model is insurance: we would be paying now to ward off bad outcomes in the future. Insurance is always priced at more than it is “worth” in NPV terms, because the cost of the bad outcomes (the over $1 million bills for cancer treatments, replacing your house and everything in it) is catastrophic, and it therefore makes sense to overpay. Even though the odds statistically may seem low, you cannot afford to be in that position.

And that’s before you get to the fact that the odds of bad climate change outcomes are way more likely than having your house burn down.

Economists based their hope of not having to give up much in growth in order to address climate change on an idea they call decoupling, which is that it is possible to generate more growth while using less energy and/or cleaner sources of energy. Economists had even posited that this sort of thing would happen on its own as countries became more prosperous. The Carbon-Kunzets-Curve hypothesis contends that as countries industrialize, they generate more greenhouse gasses per capita, but eventually hit a threshold level of income where citizens start demanding cleaner output. Think of how smog in Los Angeles in the 1960s helped propel the adoption of the Clean Air Act and its considerable expansion in 1970.

Storm and Mir used the CKC hypothesis as the focus of their inquiry, but I suspect most readers will find their findings on what they call production based versus consumption based greenhouse gas measures much more important.

Storm and Mir start by noting that the empirical evidence for CKC isn’t overwhelming:

It is fair to conclude, finally, that there is no unambiguous and robust evidence in support of the CKC—notwithstanding the fact that eleven out of 20 studies report findings (partly) in support of the CKC.

Their study focuses on the fact that the way greenhouse gas emissions are measured on a national level, both for the purpose of agreements like the Kyoto and Paris accords, as well as in past CKC studies, is to look at production based emissions.

That means these measures omit the carbon these countries consume via importing. In effect, advanced economies1 have outsourced their greenhouse gas emissions, just as they have often outsourced pollution-heavy types of manufacturing to emerging economies. On top of that, trade, and in particular the sort of extended supply chains that have become a staple of modern commerce, are an additional source of carbon emissions that aren’t captured in these national computations.

The authors used a comprehensive source, the World Input Output database, which includes carbon output from international air travel, fishing ships and even marine bunkers. They looked at 1995 to 2008; the collapse in trade and growth right after the crisis and the widely differing emergency responses made it hard to interpret the data reliably in those years.

Not surprisingly, Storm and Mir found that by leaving out trade, national governments were airbrushing out a big part of the climate change picture. Trade accounted for 26% of global CO2 emissions in 2008. Net carbon imports have also been rising strongly relative to domestic production of carbon: doubling from 11% to 22% in the EU-27 from 1995 to 2007, and in the US, rising from 6% to 16.3% over the same period. In other words, these economies were outsourcing more of their greenhouse gas generation over time.

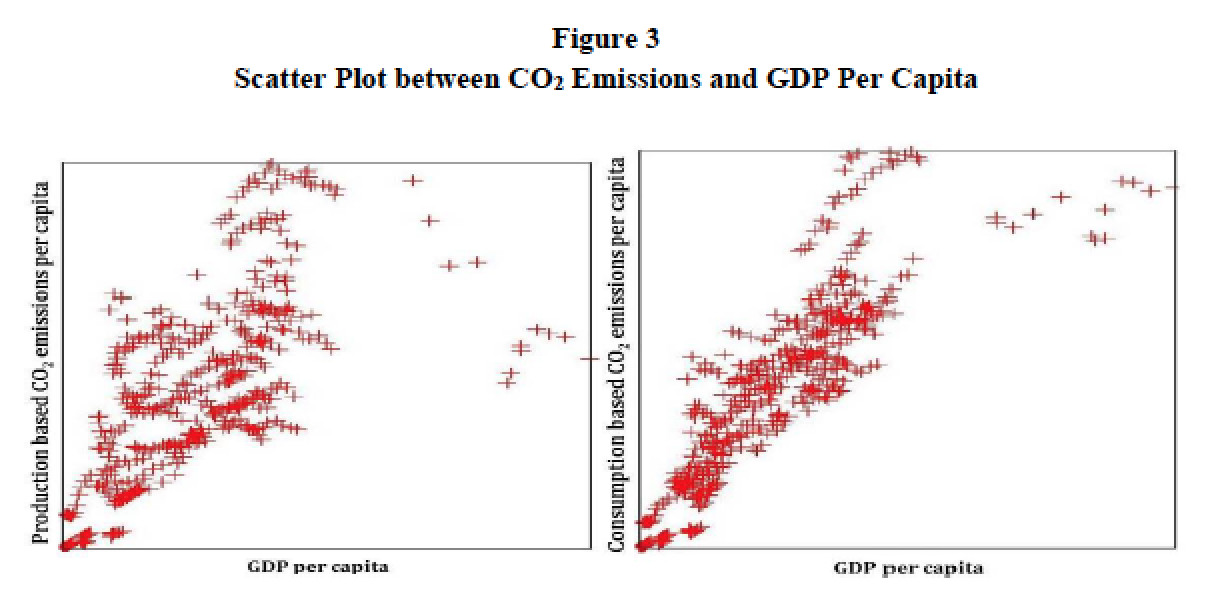

Here is where the econowonkery gets interesting. Using production-based data, Storm and Mir find support for the Carbon Kuznets Curve, as you can see from the left-hand plot below. The paper describes how they had tested several models and settled on one, and using it, determined that the threshold level of income at which greenhouse gas emissions begin to decouple from growth is at a per capita income level of roughly $36,000.

However, the right-hand chart, which is based on consumption-based carbon output v. per capita income, presents a much less cheery picture. It shows what looks an awful lot like a linear relationship: more income leads to more carbon consumption. As the authors drily note:

We cannot therefore reject the hypothesis that there is a monotonically increasing relationship between per capita income and per person consumption-based carbon emissions.

They then try plugging the data into the model they had used to determine the inflection point for the production-based carbon emissions. The result isn’t much more reassuring. It shows that there is a tipping point, but at such a high level of income so as to be useless in terms of climate change mitigation:

When we calculate the threshold level of per capita income (using equation (2)), we obtain a high level of real income per person of $113,709. This level of income is outside the per capita income range of the whole sample (as maximum GDP per capita in the sample is $96,246; see Table 3).

The implications are grim:

Our CO2 emissions data include emissions embodied in international trade and along internationally fragmented commodity chains—and hence represent the most comprehensive accounting of both production- and consumption-based GHG emissions to date. While there is econometric evidence in support of a CKC pattern for production-based CO2 emissions, the estimated percapita income turning point implies a level of annual global GHG emissions of 70.3GtCO2e, which is 40% higher than the 2012 level and not compatible with the COP21 [Paris Accord] emissions reduction pathway consistent with keeping global warming below 2oC. The production-based inverted Ushaped CKC is, in other words, not a relevant framework for climate change mitigation. In addition, we do not find any support for a decoupling between living standards and per capita consumption levels on the one hand and GHG emissions per person on the other hand….The generally used production-based GHG emissions data ignore the highly fragmented nature of global production chains (and networks) and are unable to reveal the ultimate driver of increasing CO2 emissions: consumption growth (or “affluenza”) in the rich economies. What appears (at first sight) to be the result of structural change in the economy is in reality just a relocation of carbon-intensive production to other regions—or carbon

leakage….These results should be sobering as they strongly indicate that there is no such thing as an automatic decoupling between economic growth and GHG emissions. It means we have to give up on the notion of the CKC (see also Storm 2009; Lohmann 2009). To keep warming below 2oC de-carbonization has to be drastic and it has to be organized by deliberate (policy) interventions and conscious change in consumption and production patterns…. The rich Annex-I countries which are in the forefront of technological innovation, are in the position to take the lead and also encourage the developing non-Annex-I countries to participate by investing heavily in the development of new energy technologies that are clean, efficient, and are also affordable for the developing countries. Without such change, the business-as-usual scenario looks bleak, as GHG emissions will continue to increase with economic growth and world population growth (Figure 5) and there is hardly any time or global carbon budget left. Recent projections, based on new modeling using long-term average projections of economic growth, population growth and energy use per person, by Wagner, Ross, Foster and Hankamer (2016), point to a 2oC rise in global mean temperatures already by 2030. Their results suggest that we may be much closer than we realized to breaching the 2oC limit and have already used up all of our room for maneuver (see Pfeiffer et al. 2016 for a similar warning). This carries considerable risk, as warming becomes self-reinforcing and dangerous beyond the 2oC limit, and it is the precise outcome COP21 wishes to avoid—but quite in line with our findings.

The truly disconcerting bit about reading this analysis is that this sort of comprehensive look should have been the basis for policy formulation. Instead, the officialdom has adopted the unduly flattering metrics of national production, which has the convenient effect of leaving trade-related carbon emissions out of the picture entirely. Yet if you’ve had even casual contact with data about transportation, you know that shipping is hugely costly in carbon emission terms. Only now have efforts begun to address the big carbon footprint of container ships. Cruise ships, which are even more wasteful than travel by air, have been under pressure longer to get greener, but even there, the successes seem to be limited to routes where the operators can be brought to heel, like Alaska and the US West Coast.

In addition, the national production frame pits advanced economies, that have already achieved high income levels, against emerging economies, who argue that they have a right to pollute to get richer. Shifting to a consumption framework would put the onus on rich country denizens to cut back on purchases from developing countries in general, and in particular of goods with a lot of embedded carbon. That focus would in turn put pressure on the developing countries to adopt cleaner energy sources and production methods.

Sadly, the fact that information as basic as is contained in this paper came to light only in 2016 and has not gotten the play it deserves indicates that the policy die is already cast. Or to switch to a more apt metaphor, our collective goose is already cooked.

_____

1 Canada is an exception and is a greenhouse gas exporter.

“our collective goose is already cooked.”

It most likely is. I know people want to wear rose-colored glasses, but there isn’t much that can be done now that the oceans are too hot, and becoming ever-more acidic. Check out Kevin Pluck on twitter, he has some excellent images for this kind of thing.

Turning off industry would increase the temperature by up to 1C according to Guy McPherson, due to the particles emitted from factories.

Eat, drink, and be merry, because we don’t have much time left.

I guess “Greed” wasn’t so “Good”…

Globalization is a disaster, no matter where one cares to look.

Except that in order to help mitigate the worldwide problems that we have created, it will take a global effort.

No it won’t. In fact, pursuit of a “global effort” is what prevents effective action from being taken.

If America, all on its own, abrogated every Free Trade treaty and agreement it is currently involved in, America could ban all possible imports and force their substitution with domestically produced, trade-uncontaminated equivalents. The carbon no longer dumped to no longer import things would be a significant carbon reduction right there. And the carbon no longer dumped to no longer export things to countries which banned American exports in retaliation would be another further carbon output reduction right there.

Since America could no longer be price dumped or carbon dumped upon, America would be in a position to decarbonize its own production and consumption economy without fear of being undercut by high carbon output import competition. Once America had rebuilt its low carbon national social survival economy, America would be able to ban all traces of economic or interpersonal contact with other countries which dump more carbon per capita than America would be dumping.

And that is how acting as a single separate nation on its own, America could defeat the global effort to prevent decarbonization under cover of virtue signalling excercises like the Paris Accords. A National America acting against the Global Free Trade Conspiracy, could force the pace of decarbonization in the teeth of global obstruction against decarbonization.

Such an accumulation of tidings — dead oceans wiped clean of maritime life and transformed into a soup of plastic trash, sudden mass dying-off of animals, accelerated rate of extinctions, unremittingly increasing emissions of greenhouse gases, relentless deforestation, great lakes drying up, systematic ransacking of the biosphere with greedy looters readying themselves to swoop on the remaining bits of somewhat preserved environment (such as the Arctic) — with everybody oblivious to the situation (most people), ferociously fighting off (corporations) or eschewing (governments) every meaningful attempt at addressing the predicament…

As other people succinctly said at other times and in other places: What is to be done?

Had I that “fin de race” philosophical resignation, I would enjoy the dusk of our world as far as possible and then wait for, or hurry ahead on death. But I find the situation way too demoralizing even for that.

Thank you for the in-depth article. I am still learning how many ways climate policy barely tries to discourage increasing consumption or emissions.

If you also look at it on an individual basis, carbon footprints are a strongly positive function of wealth. Figure 1 in this Oxfam report is the best example of this. Chancel and Piketty digs into the data more. As a caveat, the carbon footprint in the Oxfam report is “individual consumption,” emissions, which are 64% of global emissions. The other 36% are classified as government level and international transport emissions which I would say the benefits of are tilted much more in favor of the wealthy.

From Chancel and Piketty 2015: “top 1% richest Americans, Luxemburgers, Singaporeans, and Saudi Arabians are the highest individual emitters in the world, with annual per capita emissions above 200tCO2e. At the other end of the pyramid of emitters, lie the lowest income groups of Honduras, Mozambique, Rwanda and Malawi, with emissions two thousand times lower, at around 0.1tCO2e per person and per year. “

Here’s another question…

How would that comparison stack up against the emissions from the US military and defense contractors? Do the global 1% or the US military and defense contractors have the biggest impact? And not to forget that the 1% is contractor associated in many ways.

This has been the closest thing I have found, but I don’t know enough about emission numbers to know if there is a primary source somewhere.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/dec/14/pentagon-to-lose-emissions-exemption-under-paris-climate-deal

“The US military is widely thought to be the world’s biggest institutional consumer of crude oil, but its emissions reporting exemptions mean it is hard to be sure.

According to Department of Defence figures, the US army emitted more than 70m tonnes of CO2 equivalent per year in 2014. But the figure omits facilities including hundreds of military bases overseas, as well as equipment and vehicles.

Activities including intelligence work, law enforcement, emergency response, tactical fleets and areas classified as national security interests are also exempted from reporting obligations.”

At the other end of the pyramid of emitters, lie the lowest income groups of Honduras, Mozambique, Rwanda and Malawi, with emissions two thousand times lower, at around 0.1tCO2e per person and per year. “

All countries with little reason for heat other than cooking. Mozambique is nice, the beaches wonderful, the cities not so nice. We drove from Mutare to Maputo via the Gorongosa and Beria many years ago.

I hate to tell you, but I’ve read OxFam’s analyses on inequality before and they are terribly analytically. Their conclusion is obvious: rich people use more carbon. They fly more on airplanes and more often in first or business class, often for work as well as personally. The 0.1% flies on private jets, even more wasteful. They live in bigger houses and may have second homes. Most (but not all) eat more meat. They will pretty much never use public transportation. They consume more generally.

The problem is the information they put together to try to reach quantitative conclusions to support cases you can make perfectly well on a qualitative basis is lousy. The aren’t careful about data sources or the models they use. It’s “any stick to beat a dog”. I can never quote Oxfam because their work is so shoddy.

Thank you for the response. That is disappointing. I definitely had a case of confirmation bias when I have talked about that report in the past and did not do my due diligence (especially since it is a nonprofit’s research..). I have seen a few academic papers on wealth + individual carbon emissions that I will have to look at again.

A nice and interesting summary. I guess it should come as no surprise that economists and policymakers are using dubious assumptions and false accounting to describe the effects of climate change on economies. However what I didn’t really appreciate is the extent to which policymakers are getting climate change advice from economists, and how mis-leading that advice might turn out to be. Thus although Storm and Mir’s paper is in some ways stating the obvious in a form that economists can understand, at least it attempts some empirical analysis and might be useful if it impacts on policymakers. The scientific literature points to precise mechanisms by which future impacts will occur, positive and negative. These are frequently so extreme that you don’t need a calculator to realise that we need to do something radical. The idea that the decision about whether and what we do should be somehow dependent on global interest rates is quite frankly bafflingly insane.

On the other hand it is good to know that what all climate scientists have believed for at least a decade, that impacts are likely to be much worse than people in general believe, is slowly creeping out into the mainstream. When scientists first started suggesting that we are on course for high levels of warming, sea level rise, crop failures, droughts etc they usually were discouraged from saying these things in the media and even in papers because it was ‘too alarmist’. I would be surprised if you could find a reputable climate scientist who believes we could limit warming to 2C. Instead we should be working hard to prevent 4C.

Until we collectively recognize climate change as the exitential threat that it clearly is we will be ensuring our demise. Theclimate mobilization.org has a plan for a WW2 scale mobilization to decarbonize in a decade. Take a look at it. In my county Montgomery Co Md we got the council to commit to 80% decarbonizaion in. 10 years.

Decarbonization of what? The beltway? Shady Grove Road? 355? Or just downtown Rockville?

I’ve been saying this for years. It does little good to reduce our carbon dioxide production by simply importing rather than producing CO2 intensive products like Steel and Aluminum. Tearing down steel foundries in the US and building them in China does nothing to help global warming. But it is good to have actual data and analysis to back up my gut feeling.

Trump’s impending decision to impose “national security” tariffs or quotas on steel and aluminum imports is environmentally significant for that reason, and for another as well. Hardly any country has ever invoked the “national security” or “emergency in international relations” exception to the WTO agreements, because it’s such a big loophole that doing so could easily lead to a trade war. (As, in fact, Trump might.) But if the US can impose tariffs in the name of “national security” on steel imports, other countries can certainly do so to prevent global warming. All sorts of interesting trade barriers directed at alleviating global warming might be possible.

And if they are not possible under current Free Trade Agreement rules, it might lead to public upsurges in favor of abrogating those rules and cancelling membership in those agreements on the part of every national government country which wants to forcibly decarbonize, including by excluding economic invasion by carbon dumpers from outside their own borders.

Well, that post was like a 2 by 4 upside the head.

Makes perfect sense, though.

http://www.drawdown.org/

Anyone had a chance to review/read through this book? Seems like they’ve outlined a pretty comprehensive set of strategies to reduce carbon emissions and sequester carbon back into the soil.

I was thinking of picking up a copy, but would be curious to hear what nakedcap community has to say.

I still am not entirely sure what to think about this list.

First, a technical point. This list uses “CO2 equivalent” which is the amount a greenhouse gas warms the atmosphere compared to an equal amount of CO2 over a fixed timespan! That fixed timespan is usually 100 years, but some of our CO2 stays in the atmosphere for over 100,000 years. This is a great article about it. Similar to the economic discount rate in Yves’ article, if you decide to care about the distant future (say 300-500 years or more) the only two greenhouse gases that really matter are CO2 and HFCs/CFCs (stuff from refrigerants). The technical choice of this timespan of comparing CO2 to other greenhouse gases strikes me as a huge hidden ethical choice. If you value the Earth in 500 years as much as you value the Earth in 100 years, the Drawdown list looks very different.

Second, I feel like the list glosses over a root cause of many environmental issues and climate change: unchecked consumption. I like the framing of Univ. of Manchester Professor Kevin Anderson that if the 10% richest people in the world lived like the average European (a person better off than most in the world!), global carbon emissions would drop by a 1/3. So much of the problem is how we live, I worry that the Drawdown list is a deliberate attempt to avoid pushing for political and societal change.

Lastly, I really liked this interview with Kim Stanley Robinson on capitalism’s inability to care about the future.

Thank you for the link to the Kim Stanley Robinson interview. I greatly enjoyed his Mars trilogy and found a new respect for him reading this interview. I particularly resonate with his views on the importance of art. But I’m much more pessimistic about our chances of casting off the Neoliberal yoke before a serious crisis forces change. I also disagree with his dichotomy between adaptation and mitigation. I don’t view adaptation solely in terms of its being a shrug to Neoliberalism. Climate Disruption has reached a point where both adaptation and mitigation are critically necessary and adaptation cannot be viewed as a capitulation to the way things are as much as a necessary response to the ways things are until they can be changed. I was also intrigued by the “After the End” exhibition the Robinson interview was part of. Thanks!

The Kevin Anderson lecture is quite good.

I don’t think he’s trying to, but his description of carbon capture and storage makes the idea seem middle-school-kid-ranting level of ridiculous.

I can’t believe we’re seriously relying on these ideas to save us…..especially when there’s no real funding to develop them.

“Living more like Europeans” is more possible in big cities and the suburbs around them than in isolated small cities and towns in the midst of vast thinly populated landscapes. So the big cities and their metro areas is where “living more like Europeans” will have to start. Is there a way for Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas to do that without being obstructed by the States and FedGov under which they live?

As to people living beyond the big SMSAs, they will have to do what conservation lifestyling they can on their own in their anti-efficiency-infrastructure circumstances.

And if you can stand it:

http://cassandralegacy.blogspot.it/2018/02/our-only-hope-for-long-term-survival.html

Recalling an older Chomsky, that “human intelligence” may be an oxymoron.

I recently had a short tour of a Marine lab.

The tour guide claimed 90% of the kelp was gone off the California coast, and that is a problem for much marine life.

The optimists suggest human engenuity will allow substitutions and work arounds to compensate for climate change effects on humans.

Other life forms are already seeing the climate change effects and they have less ability to compensate.

>Economists have not been as vocal in the climate change debate as one might expect.

I would not expect economists to be vocal at all as they have pitched more GDP = unalloyed good thing for many years.

The economics profession is a petrochemical based profession as its promotion of unlimited growth message depends on the availability of inexpensive energy.

Some small guidance for the economics profession is in a recent editorial, in the Feb 25, 2018 LA Times, by a Financial Times editor

Search for “The Growth Delusion by David Pilling — why GDP is misleading”

Most of the economists work for the Globalist Free Trade Conspiracy one way or another. So why would they ever look at the GFTC’s contributions to global warming?

I believe the 2 degrees Centigrade target was chosen for political not scientific reasons. We know the global temperature is increasing, and the rate of increase seems to be accelerating. We know the present levels of CO2 were last reached eons ago when the Earth’s climate was very different. I doubt any scientist would claim to predict how the global climate will evolve from the present conditions. How could anyone say a 2 degrees Centigrade increase is a ‘safe’ temperature increase? I doubt anyone can predict where the global temperature might end up given our present CO2 levels. There are too many unknown factors in the Earth’s climate systems and of course what is unknown cannot be represented in complex climate models. I think the 2 degrees Centigrade number succeeded in suggesting we know more than we do and that we can somehow fashion budgets to safely allow further additions to the CO2 in the atmosphere. The budgets also support political posturing and blame casting and provide theater to give the appearance of action. What increasingly appears as a truly existential threat can be morphed into political theater supporting cosmetic tweaks to support business as usual. Is it really surprising that economists who were complicit in crashing the global economy would assume a similar role in dealing with Climate Disruption?

We are headed toward an unhappy future but for the present I am most worried as I sense growing calls for action. There are actions we might take to mitigate those problems we can foresee and limit the damage we continue to do. Plant a tree, ride a bike, plant gardens. Now that the Market based CO2 budgets are showing their true nature we will hear more and louder urging to launch large scale efforts to geoengineer a better future world. The Climate Disruption we already face is very frightening but the potential results of geoengineering projects are truly horrifying. Unfortunately without some radical social and political change we no longer have any say in what ‘we’ should do about Climate Disruption. Mindless action on a global scale brought us to the present brink. Further mindless action to ‘repair’ a system we don’t adequately understand would be like handing a gorilla a heavy wrench to repair your computer.

The 2C limit is an arbitrary, easy-to-remember number. I think this article outlines it well.

Any amount of global warming is likely dangerous once we feel its full effects (1C, 1.5C, 2C) but policymakers decided to focus on 2C because it was thought to be achievable. It is already too late for 2C. A paper last year said we have a 10% chance of 2C warming by 2100. But that is also using the year 2100 as a benchmark! The warming will continue past the year 2100..

We are close to 2 dec C by 2030. The warming trend is a growth curve, not a straight line.

Growth curves have exponential parts.

The Carbon-Kunzets-Curve hypothesis contends that as countries industrialize, they generate more greenhouse gasses per capita, but eventually hit a threshold level of income where citizens start demanding cleaner output.

Individual country’s curves are irrelevant and a distraction. What’s material is the sum of all the county’s curves, or the whole planet’s curves. This coupled with discussion of how all countries become “developed” and a test or set of tests to determine each country’s success in becoming “developed”.

I call bullshit on this Carbon-Kunzets-Curve hypothesis as just another clever excuse by well paid economists (paid by whom one has to ask) for developed countries to avoid the obligation to the planet and its people.

Exactly! There is no plausible theory I can think of why when a population reaches a certain level of average prosperity it starts to use less energy per capita. The curves in the post, on both production and consumption sides, are pure artifacts–correlations without causation. On the other hand, we can see how institutions and culture can drive the “de-coupling” of energy consumption from economic growth and population in places like California, and not in other places like Texas or USA as a whole. https://www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/ca-success-story-FS.pdf I suspect the motive behind the CKC curve is to persuade us that economic growth and the invisible hand will solve the GHC problem and we should, therefore, do nothing institutionally.

There is ONE carbon dioxide neutral country, that is Bhutan.

from:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bhutan

” It currently has net zero greenhouse gas emissions because the small amount of pollution it creates is absorbed by the forests that cover most of the country. While the entire country collectively produces 2.2 million tons of carbon dioxide a year, the immense forest covering 72% of the country acts as a carbon sink, absorbing more than four million tons of carbon dioxide every year.”

With Bhutan’s 800k population and the world’s 7.3 billion population, this calculates to (800E3/7.3E9 )* 100% = only 0.011% of the world’s population is not adding to the world’s CO2 load.

Not much cause for optimism here.

But Bhutan can be used as an example of what a governed state can do to become a carbon neutral or net zero carbon participant. The trouble is the economy and ciluture of Bhutan is just about 180 degrees opposite from all other Westeren civilization countries that using Bhutan as a model is seen by most as laughable.

Yet, It is a model that might be emulated worldwide to stay further catastrophic consequences. Unfortunatly, no one is going to do that. The hope is we can have our cake and eat it too through advancements in technology. It’s a pipe dream but one that seems to be the majority consensus that allows us to pretend that we will avoid the extinction level calamities predicted. By any measure of economics, this solution is just pure folly and absolute 100% conjecture. And, that seems to be the course of action and preeminent thought in surviving this condundrum. It makes no sense.

At least one economist has been very vocal on this subject, for a long time now: Herman Daly; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herman_Daly.

From the entry, for the sake of brevity: ” an American ecological and Georgist economist[1] and emeritus professor at the School of Public Policy of University of Maryland, College Park.” I believe he also worked an UMKC with the other heterodox economists. He’s now quite old; he’s been pointing out that the economy happens within a “box” – the Earth – for quite a long time. One of the first economists to notice that the earth is round.

His legacy: http://www.steadystate.org/herman-daly/.

I’ve quoted him before. He was especially critical of “comparative advantage” theories, because the concept depends on capital and labor not being mobile; and opposed international capital transfers for that reason.

Herman Daly has tenure. He is somewhat free to pursue lines of thought which are not to the Globalists’ taste.

“Nicolas Stern, who wrote the Stern Review, argued for urgent action on climate change, had to assume a discount rate of 0.5% in order to make the damage done by climate change roughly 100 years out to matter in economic terms.”

So that’s why economists dismissed the alarm calls – from Daly, among others. Doesn’t it really mean that economics, as a discipline, simply doesn’t live in the real world? Global cooking doesn’t matter because of an interest rate – how could someone SAY that and not realize that it’s cuckoo? How could others HEAR it and not dismiss the speaker out of hand?

OK, I do know the answer to those questions: no one is so blind as one whose wealth depends on not seeing. Actually, Daly dealt with that one, too: he said that early on, economists sold themselves to the merchant class. That’s why they ignore the real limits represented by land, etc. It means the field is fundamentally corrupt – and this applies even to otherwise excellent economists like Dean Baker. It’s at the core of the “liberal” ideology.

The 2 big reasons a full-scale military mobilization will be the best way to tackle climate change dovetail: we need to stop with our unsustainable, profit driven, planet destroying capitalist free market insanity and replace it with a calculated use of all our resources which would otherwise have been frittered away doing free market stuff. No other approach takes care of the situation with the resources that were once used to create it. Karma. But it terrifies us all because it requires a complete turn-around of everything we have been doing. And to do this we have to be brutally honest about how serious the situation is. And that it will take decades to fix it. There’s no way in hell that we can keep capitalism humming along to make a profit to invest in this; no way we can tax capitalism as we go. That’s like two steps backward for one step forward.

I am not so sure of the assumption that economic growth necessarily takes a hit from aggressively reducing green house gas emissions. Probably traditional measures of growth get hit. But, jobs and happiness probably don’t need to take a hit.

Looking at the US there are plenty of people who are un(der)employed. Subsidize renewable energy and efficiency and maybe traditional growth measures go down but jobs likely go up. Build high speed electric rail that can run on renewables to replace significant chunk of air travel and decrease emissions with little loss of jobs or ability to enjoy travel experiences. Research and education are areas that can have a low carbon footprint and high happiness jobs, while providing needed help in zeroing out human carbon emissions. Consumption of stuff needs to go down. The conflation of stuff with happiness is part of the problem. Switching to experiences instead of stuff could reduce carbon, maintain employment, and probably make everyone happier in the end. It probably breaks traditional measures of growth, but I don’t expect any regular people would notice, other than the fact they have jobs and there are lots of things to do with the money from those jobs.

It is not free market. I see it as leveraging one of the central theses I see in MMT that the governments most powerful tool is that it print the money, and can therefore afford anything for which the real resources are available to supply. Were a government to spend in order to create the resources for which it needs (skilled workers, skilled researchers, plants to build wind turbines and solar, etc…) then supply is even less of a constraint. So, I see not as can climate change be solved, but do we have the will to solve it. Unfortunately, will seems to be something lacking.

With respect, the basis for this is absurd.

“Greenhouse gases per capita” – what? Nature doesn’t care about that. Just total greenhouse gases.

Under current fake-treaties, a nation that produces low per-capita greenhouse gases, but has zillions of people and massive total greenhouse gas emissions, is more virtuous than some sparsely populated nation with high per-capita gas production but very low total emissions. Which is absolutely the opposite of reality.

If we really want to save the world, we need to focus on the bottom line. What matters is the total greenhouse gas production of a nation, divided by its vegetative surface area. A nation may choose to have a modest population living in comfort, or a massive population living in misery. Let’s make that explicit, and give people a choice. Oh, but that would hurt the oligarchs whose profits depend on cheap labor…

By focusing only on per-capita emissions, we are NOT saving the world. We are making it easier for the elites to crush the entire global working class into a subsistence level standard of living.

Since it is people who would have to do the de-carbonizing, and people care about things like per capita fairness and per capita sharing of sacrifice, per capita emission of skycarbon will have to be thought about by people working to reduce that emission.

Since nature doesn’t care about “per capita” carbon skydumping, people will have to decide what per capita emission of carbon per person times all the people in the world will add up to not-too-much-for-nature-to-tolerate. And then achieve it and live, or fail to achieve it and die.

Since plants can be managed in such a way so as to keep and store in the soil the carbon they eat out of the air, massively improved plant growth systems can reduce skycarbon at the “suckdown” end even as we are reducing skycarbon at the emissions-end.

Already too late. 800 ppm and 6-8 degrees by 2100. Runaway train (see Tainter). This is simply ARGUING about how to rearrange the deck chairs on the Titanic.

Happened to start reading the late, great paleontologist/evolutionary-biologist Stephen Jay Gould’s 1992 collection of essays Bully for Brontosaurus over the weekend. In the prologue, seemingly struggling with the contradictory points of view induced by his deep-time studies from paleontology on the one hand and his own lover-of-civilization humanism on the other, he writes:

the Elite may migrate to another planet (their progeny can perhaps return following the next Ice Age), while those remaining here are *recycled* by whats coming….

Econometrical models tipically say “other things equal” and that includes climate, sea levels or ocean’s pH.