Yves here. I am sure readers will have insightful comments, but let me offer three thoughts. The first is that the article offers “uneven access to technology” as an explanation for the wage gap and therefore difference in general prosperity between coastal cities and rural areas in the US. It then offers a variant of the “let them eat training” remedy.

This seems like looking at a symptom and treating it as a root cause. We’ve had at least 40 years of erosion in the caliber of primary education in the US, measured among other things in the falling standing of US students in international comparisons and the recalibration of the SAT in 1994 as a result of falling test scores. Recall that, as Elizabeth Warren pointed out in her 2003 book, The Two Income Trap, that a, arguably the, driver of rising home prices was increased competition for homes in “better” school districts. That was a reflection of rising inequality and the deterioration of the perceived and probably actual teaching in “lesser” schools.

Another factor has been the erosion of funding (and let us not forget adminisphere bloat) and resulting rising costs of public universities. It used to be that bright kids who had gone to not-so-hot primary schools could if they applied themselves, make up for what they had missed in their freshman year in college, and an inexpensive public college was worth the wager. That’s not such a sound bet now.

Let us put it another way: how do you think someone from the boonies, who was a self taught computer genius, would fare if they tried making their way in a coastal city now? I know someone who fit that profile (no college degree on top of that, but he was doing internet stuff so early that he “owned” a block of class B IP addresses) and by the early 1990s was in a very well paid Wall Street IT job at one of the cutting-edge firms. That sort of transition would seem unthinkable now due to the much greater emphasis on credentials, which institutionalizes class differences.

A second factor that gets nary a mention is inadequate government spending in the post crisis era and undue attention to the state of asset prices, as opposed to worker wages. Goosing asset prices to salvage the banks, as opposed to making them clean up their balance sheets and using fiscal spending to offset the impact of the deleveraging, would have resulted in a less unequal distribution of wages and growth, which most economists are willing to concede is slowing down growth. A less finance/asset price centric recovery is likely to have resulted in more moderate increases in urban housing prices, which also somewhat lower the barrier for people from outside to try to relocate there.

Finally, I suggest readers contrast this post with the one we ran earlier today from VoxEU, which has a real sense of urgency about places left behind which is remarkably absent here. This isn’t the fault of the Bruegel author but of the underlying pieces that she has summarized.

By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and previously an Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Originally published at Bruegel

Both in Europe and the US, economists are starting to notice how the economies of cities have been sometimes diverging from the economies of states. While some areas thrive, others may be permanently left behind. Maybe it is time to adopt a more clearly sub-national perspective. We review recent contributions on this issue.

In this week’s Free Lunch, Martin Sandbu makes the very interesting claim that “all economics is local”, and that sustainability of economic strategies depend on their local effects. Many studies show that intensifying economic vulnerability at the local or regional level is closely associated with anti-establishment votes for political disruption or for extremist or populist parties. The deindustrialisation that rich countries have undergone at the hands of technological change (and to a lesser extent globalisation) has created a class of people who are economically left behind, rebelling against the liberal economic and political order.

It matters that change has not just disadvantaged particular socio-economic groups, but that it also affects different places in very different ways. A shift in economic structure from labour-intensive manufacturing to services has different distributive consequences not only across sectors, but also geographically. In particular, it is bad for places traditionally hosting manufacturing — mid-sized factory towns — and good for knowledge-intensive places such as the big cosmopolitan cities. What makes structural change so hard to manage is precisely how it tends to hit the same group with several blows: those already hurt by working moribund jobs are doubly hurt because they live in places particularly concentrated in those jobs. Sandbu offers three principles to approach this change in perspective.

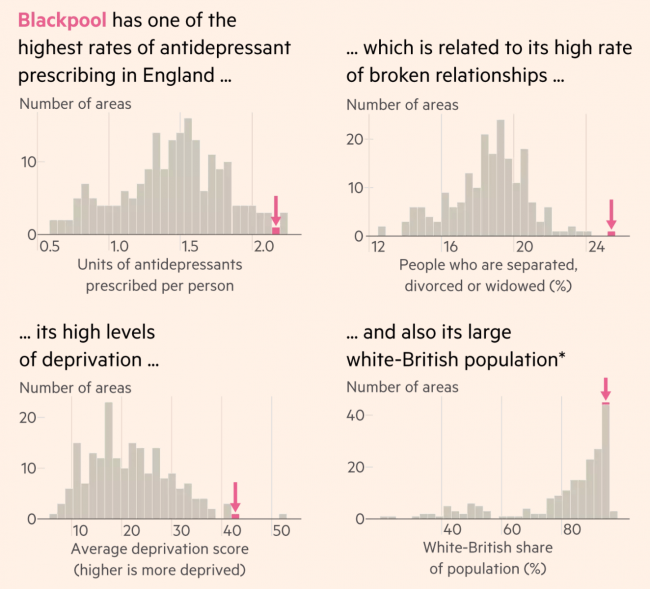

Other authors in the FT have looked at this issue before. Sarah O’Connorfor example had a long must-read report on the city of Blackpool in the UK, arguing that the city embodies much of what is going wrong on the fringes of Britain and wondering whether there is a way to save the towns that the economy has forgotten. Economists in the US often contrast the dynamism of America’s coasts with the malaise of its heartlands. But in Britain, it is increasingly the reverse, with seaside towns like Blackpool exporting healthy skilled people and importing the unskilled, the unemployed and the unwell.

More than a tenth of the town’s working-age inhabitants live on state benefits paid to those deemed too sick to work, antidepressant prescription rates are among the highest in the country and life expectancy, already the lowest in England, has recently started to fall. To some extent, Blackpool shares some of the traits of desperation that we discussed in a previous blog review regarding the US opioid epidemics (Figure 1 below). O’Connor argues that the story of Blackpool is a story about the failure of national policies to support places on the edge, but it is also a story about how, in the face of necessity, people are trying new ideas to turn things around and break the local vicious circle.

Source: FT

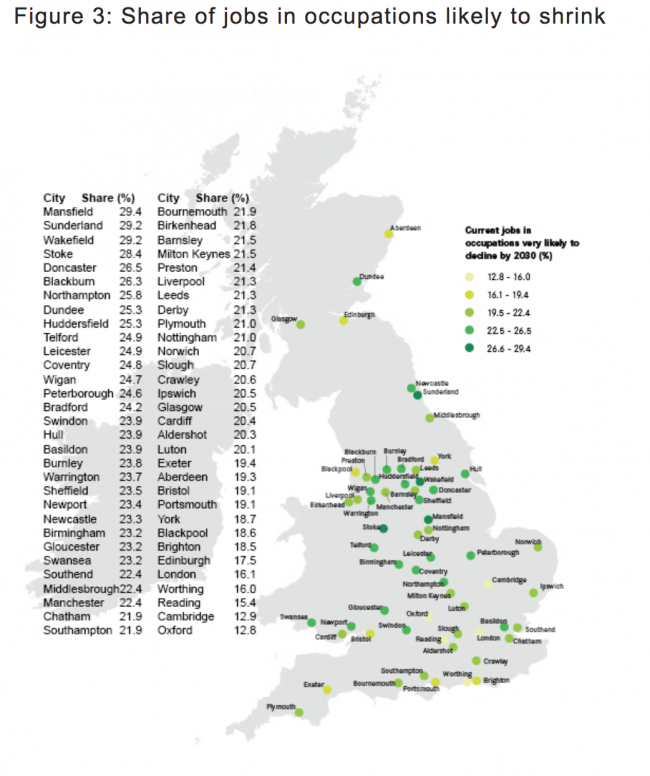

The Centre for Cities released its 2018 report looking at the impact of increasing automation on 63 of the UK’s cities, which gives a clear picture of the differences at the sub-national level. Overall, the report finds that one in five jobs in cities across Great Britain is in an occupation that is very likely to shrink. This amounts to approximately 3.6 million jobs, or 20.2% of the current workforce in cities. In places like Mansfield, Sunderland, Wakefield and Stoke almost 30% of the current workforce is in an occupation very likely to shrink by 2030 (Figure below). This contrasts with cities such as Cambridge and Oxford, with less than 15% of jobs at risk.

While big cities are relatively less exposed to occupations likely to shrink, they are nevertheless likely to see a great deal of disruption. For example, London and Worthing have a similar share of jobs likely to see a decrease in demand (16.1% in London, 16.0% in Worthing), but this translates to around 908,000 jobs in London – 25% of all jobs at risk in cities across Great Britain – and only 8,400 jobs in Worthing, which is just 0.2% of all jobs at risk in cities. All cities are likely to see jobs growth by 2030 and around half of this will be in publicly funded occupations. Yet, looking at the private sector, there is more variation – some cities (mainly in the South) will see many more high-skilled private sector jobs growth, whereas others (mainly outside of the South) will see a growth in lower-skilled private-sector work. Significantly, the report also finds that it is the same cities which are most at risk that also voted to leave the EU and are more dependent on welfare.

Source: Centre for Cities report 2018

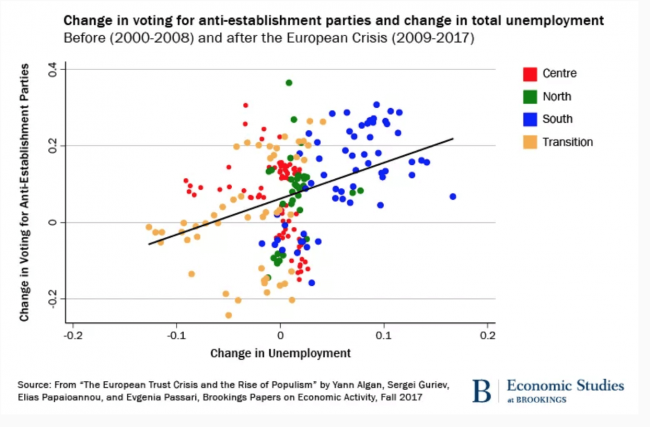

In a recent paper, Algan, Guriev, Papaioannou and Passari look at Europe more broadly. They investigate the European “trust crisis” and the rise of populism taking a sub-national perspective, and looking at the evolution of unemployment, attitudes and voting from 2000 to 2017 in more than 200 regions throughout 26 European countries. They find a strong relationship between increases in unemployment and voting for non-mainstream, especially populist parties, as well as a correlation between the increases in unemployment and a decline in trust in national and European political institutions. The correlation between unemployment and attitudes towards immigrants is muted, especially for their cultural impact.

The authors also extract the component of increases in unemployment stemming from the pre-crisis structure of the economy, and in particular construction share in regional value added which is strongly related both to the build-up and the burst of the crisis. Crisis-driven economic insecurity is found to be a substantial driver of populism and political distrust. An important policy implication from the European economic crisis is that national governments and the EU should focus not only on structural reforms, but also on protecting the trust of their citizens from the corrosive effect of economic insecurity.

Source: Brookings

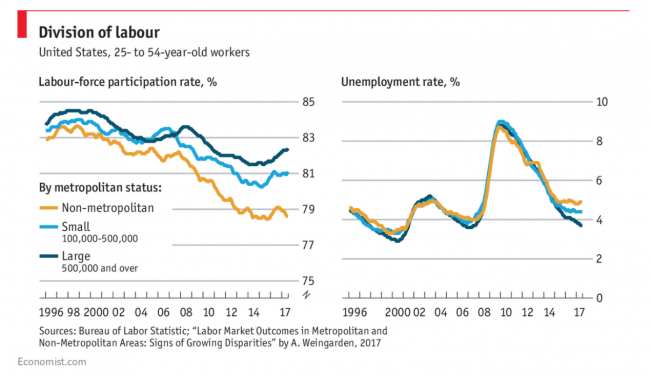

As for the US, The Economist has a striking chart (see below) showing how the economies of States and cities are diverging. The chart is based on a recent paper by Alison Weingarden of the Federal Reserve Board, who estimates that since 2007 the gap between the labour-force participation rate of “prime-age” workers aged 25 to 54 in big cities and similar workers in rural areas has grown from 1 to 3.8 percentage points. Since 2015, the difference between the unemployment rate of prime age city-dwellers and their rural counterparts has increased from 0.3 to 1.2 percentage points.

Source: The Economist

A longer Economist article wonders what can be done to help marginalised regions in the rich world. Across a wide range of industries the share of output generated by America’s top four metropolitan areas for each industry has risen, often substantially. In the financial industry their share of output rose from 18% to 29%, and in retail, wholesale and logistics from 15% to 21% between 2002 and 2014. The Economist offers several reasons why the poorer regions of rich economies did not adjust as well to the winners-take-more geography of globalisation. One is that technology seems to be moving from place to place less easily than it used to: globally competitive firms have got better at mastering complex new technologies, but diffusion of technology from top firms in one country to laggard firms in the same country has slowed down. A second aspect is that labour mobility – even in America – has become lower. On one hand, high housing costs in the successful cities makes relocation difficult. On the other hand, the push to leave failing places has weakened and the growth of the welfare state limits the chances that declining cities will disappear.

Rather than attempting to seed clusters – the Economist argues – governments could instead focus on spreading know-how in order to increase the attractiveness of laggard regions to productive firms. Improving the investment climate in struggling areas could help, as would improving educational opportunities. Ronald Brownstein at The Atlantic has a very interesting account of how mayors at the local level are trying to channel economic growth to neglected places.

Nitpick:

I think you have got your counterfactuals mixed up in paragraph 5 of your commentary, in the sentence starting “Goosing asset prices…would have resulted in…”.

In relation to the points on labour mobility in the article itself, high housing costs have been an objective of policymakers in Britain since the Thatcher government – it’s not an unintended consequence of uneven patterns of development, but an intentional political strategy.

Can you please explain why they want high housing costs? I get “the landlords make more money”, but apart from that?

The wealth effect is supposed to compensate for the lack of actual earnings increases — which themselves would require corporations really to pay better wages overall (which the Conservatives and the 3rd way Labour neither planned nor viewed as realistic).

In a broader sense of course Tory members and their voters are invariably property owners, so rising property values makes them richer. Its really that simple. Its one reason why selling Council houses was such a political masterstroke by Thatcher.

“how do you think someone from the boonies, who was a self taught computer genius, would fare if they tried making their way in a coastal city now?”

Well, if they were the top math student out of 50 million applicants to the Indian Institute of Technology, were young and up on the latest software, they’d do great and probably be lured to Silicon Valley.

Sarcasm off.

“Boondocks”, Daniel Boone’s waterside outpost on the wild frontier of the Ohio River.

When I made the mistake of spending a year studying computer science (I learned that I am terrible at writing code and really dislike doing so:-) one of my classmates was a young man from a Vietnamese family who was only there because he needed to get the degree. He already knew what was being taught. We had a a couple of team projects in classes we shared and the only contribution I could make of any value was writing the papers and presentations. He could design, code, test and finalize the programs we worked on in a matter of a few hours, was fluent in an amazing number of languages, knew SQL etc. etc. and was only 20 but was at an impasse in his career because he didn’t have that piece of paper. At least with the low tuition at our Vancouver suburbs located University he wouldn’t have a ludicrous amount of debt by the time he graduated but the whole situation seemed ridiculous.

I think UK seaside resorts like Blackpool (birthplace, incidentally, of that great actor John Mahony, who died yesterday) are to an extent a unique case. They grew up in the 19th Century to give respite to holidaying working class (and occasionally wealthier people) from the big industrial cities. Cheap holidays to Spain killed them stone dead. One reason they are now so deprived is that the surplus of cheap accommodation makes it too tempting for public authorities to use them as a cheap way to house the poor. This has set up a negative spiral whereby nobody really wants to holiday in them because of the social problems. The only holiday towns which have held their own are those within easy reach of prospering cities, such as Brighton, which has become a kind of refugee centre for London hipsters.

I do wonder if there is any solution for towns like this except managed decline – i.e. simply allow them to shrink in a reasonably natural manner.

One point of comparison by the way between places like Blackpool in the UK and somewhere like Atlantic City in the US that always puzzled me is why in the US so many houses were cleared and demolished, while in the UK they would just rot. I couldn’t believe it when I walked around the back of the Casino strip to see so many empty lots, with occasional buildings standing like random teeth in the mouth of an octogenarian. Apparently its down primarily to the differences in tax codes and mortgage rules. There is a much greater incentive in the US for local authorities to demolish unused buildings, in the UK its better for the owners to just let them sit there.

One possible explanation, wood frame houses with siding are easier to demolish. From My limited understanding of UK housing, you all use much more brick and stone (traditionally)

In the US banks penalize cities (mortgage-wise) with a high vacancy rate. See this cartoon by Ted Rall about the destruction of Dayton, his home town: http://rall.com/2015/01/28/the-gutting-of-dayton-why-my-city-is-gone Let us be thankful that benign neglect is more the norm over here.

Cities are centers of capital accumulation. There was a little problem of them continuing to harbor captive working class populations in the early period of deindustrialization, but they have been nicely hollowed out/made safe for the ruling class in much of this country now, and the accumulation/wealth polarization is accelerating.

The Economist magazine may very well be one of the last sources of information for economic advice any struggling community or state should be taking.

It literally was the magazine that pushed for so much of the neoliberalism that brought up this current crisis.

The issue is that there is very little effort to try to make amends for those who have been hurt the worst by the economy. It is only now that the rich are not getting their way 100 percent of the time that they are desperately trying to keep the disastrous status quo going.

I think that the issue is that we have reached a point where the media may try to beguile people, but the economy has reached a point where people who have suffered the worst are not buying it. The rich, whose greed was the root of these problems is desperately trying to keep the looting going. They may have reached the limits of propaganda here.

That said, it is totally not a surprise that there is a correlation between unemployment and other economic factors with the support of out of mainstream politics.

Interesting point. If one is interested in getting decent economic insight, what should one be reading, besides this site? Genuinely interested.

Two points RE: “uneven access to technology”

First of all, this could be translated as “uneven access to money”. The article states “technology seems to be moving from place to place less easily than it used to” with a complete lack of agency as if tech just moves on its own. More (or moar as the case may be) tech doesn’t do much good as a solution if you have no money to acquire it. Generally the East Podunks of the world have far less disposable income than major metropolitan areas and my guess would be that the initial installation/implementation costs for new systems are comparable in both small and large cities.

Secondly, the assumption seems to be that more tech will be automatically beneficial. While some new tech is clearly an improvement over older methods ( I prefer excel to an abacus for example), a lot of new tech these days is a result of planned obsolescence rather than as a response to a genuine need. I really hate the business model whereby tech companies stop servicing a perfectly good platform after a number of years, forcing you to buy the new version which may or may not work as well. This often comes with many unintended complications which all have their costs too. We don’t need to have every company or municipality constantly adopting moar tech just so tech companies can increase profits. I am not an IT person however I spend an inordinate amount of time every day testing software for my department because of the perceived need for constant upgrades.

“The deindustrialisation that rich countries have undergone at the hands of technological change (and to a lesser extent globalisation) has created a class of people who are economically left behind, rebelling against the liberal economic and political order.”

What’s ‘liberal’ about our current economic OR political order?

It’s a question that I always have when I hear about the rise of populism. Why, when you don’t like the way things are going for yourself and your family, do all these people start voting for politicians that are to the RIGHT of the politicians that made their situation WORSE in the first place?

I mean, I can see not trusting the current Democrats to help, but why go to the RIGHT of Republicans for answers when it’s just going to be a more extreme form of what you’ve been getting for 40 years? Why wouldn’t they go to the left of Democrats and look for LABOR representatives or some such?

It is ‘liberal’ in the sense that it is full-on for Capitalism. Freedom (from exploitation), generosity and tolerance are a different ‘liberal’ entirely.

People go RIGHT because they don’t understand what is going on, they are offered no other alternative, and LEFT has been demonised relentlessly for the last one hundred years or more.

If you go left you will be beaten in the streets

Imprisoned,

or killed.

If you go right you will beat the left

in the streets

and kill them.

I believe the analysis presented uses too much data aggregated to obscure what is happening to the economy. For example take the observation: “… the share of output generated by America’s top four metropolitan areas for each industry has risen, often substantially. In the financial industry their share of output rose from 18% to 29%, and in retail, wholesale and logistics from 15% to 21% between 2002 and 2014.” These poster-child industries citied for the growth of their output — the fianancial industry and the retail, wholesale and logistics industries — produce what exactly besides a growing share of output? Maybe I’m jaded — I imagine the railroads saw a growing share of the national output in America’s post Civil War era — but that growing output represented the ability of their regional monopolies to extract rent from the farmers who produced the meat and grain the railroads carried to market. The game may be changed in certain details but how are finance and re-selling different than the old-time railroad monopolies? And citing the “share of output generated” with an assumed relation between it and employment — what is that relation exactly?

The chart showing the share of occupations likely to shrink in a selection of cities in the U.K. hides more than it tells. What occupations are likely to shrink? Why? The worst case cities roughly double the percent of occupations likely to shrink in London but on-the-other-hand as the post indicates the total numbers of jobs disappearing from London dwarf the numbers for the worst case cities. The post concludes from these city statistics: “While big cities are relatively less exposed to occupations likely to shrink, they are nevertheless likely to see a great deal of disruption.” From this analysis the post returns to the theme of the title and initial paragraphs resuming discussion of states and cities. It compares “major” cities with the more rural cities to assess the State. But a State consists of cities and their surrounding areas. How well do the cities serve as proxies for the economic conditions of their surrounding areas and smaller towns? [A few other questions come to mind — do the city job statistics take BREXIT into account and if so how well? How is it that Cambridge and Oxford are so secure? (Maybe the U.K. needs to hire some University Presidents from the U.S. to help them get things right./s)]

Reading between the lines this post suggests but obscures what to me seem deep flaws in the structure of the U.S. economy and apparently also in the economy of the U.K. and other European countries. “Crisis-driven economic insecurity is found to be a substantial driver of populism and political distrust.” But those who rule, supported by the economists who serve them, are concerned but not concerned enough to do anything of substance.

. . . These poster-child industries citied for the growth of their output — the fianancial industry and the retail, wholesale and logistics industries — produce what exactly besides a growing share of output?

Whenever I hear or read about “fintech” my mind interprets it as “skimtech”. There is no production, only extraction, taking a cut of a transaction. As for the retail, wholesale and logistics industries, again there is no production, but somebody has to sell and ship Chinese made crapola.

Globalization is a disaster, wherever one cares to look.

Can’t speak to the UK, but a huge ignored factor is the failure to enforce antitrust and the resulting consolidation and barriers to entry for new companies. The idea that monopolies are ok so long as the average consumer benefits from lower prices is breathtakingly short-sighted and a killer for flyover country,which ends up reduced to providing resource extraction. That is exacerbated by the increasing regulatory and economic burdens that disproportionately affect small enterprises which, let’s face it, are the only kind that can make it outside population centers. I’ve lost count of the number of proposals to promote “value added”ag, etc, that foundered on the rocks of compliance issues compounded by trying to take on the big players.

We have actually seen a change that (might) push things in the right direction, namely the cap on real estate tax and mortgage deductions, incentivizing movement out of expensive places. Ask in ten years if it worked.

Yeah, things have changed re technology. Would Silicon Valley be interested anymore in hiring the type of people in this losing firm (http://static4.businessinsider.com/image/53ad82026bb3f7237a3347bf/where-are-they-now-what-happened-to-the-people-in-microsofts-iconic-1978-company-photo.jpg) anymore? Would they hire drop-outs like Gates, Zuckerberg and Jobs anymore?

What you had to say about erosion in the caliber of primary education in the US I find even more interesting. This is not new by any standard but has been going on some 60 years or more – at least. Robert A. Heinlein wrote about this subject extensively in his 1980 book “Expanded Universe”. I wish that I could upload that chapter here. Heinlein kept his correspondence over 40 years by then and noted how by the mid-fifties handwriting and spelling had deteriorated noticeably.

By 1980 a letter from a high-schooler was sometimes illegible and such defects were showing up in college kids. What showed this up was that letters from the Commonwealth, Scandinavia, the UK and Japan were inevitably were “neat, legible, grammatical, correct in spelling, and polite.” By now I would say that the rest of the world would have caught up on this trend. He noticed the vast variety of subjects covered in his father’s textbooks, what he had learnt in school and what he saw was in the education system of 1980.

Of course this was all before neoliberalism turned its attention to schools to starve them of funds and to turn them into second-class profit centers. And it is these sorts of kids that have to cope with a changing world. I sometimes wonder if the kids in those depressed areas had what amounted to a 19th century education (college or university standard nowadays) whether they would have been better equipped to cope with these changes.

That Cambridge & Oxford do well conforms to 2008 predictions for University Towns as financially driven when there are no jobs & therefore more students going to school or staying in school.

It isn’t the banks that have all the money, or the most, it is the insurance industry. Where more is done there is more to insure.

Insurance for the people sitting at desks is lower, or laid entirely upon them as independent contractors.

That AIG had to be bailed out and the American Citizen became the reinsurer of the reinsurer meant a lot of people in finance, or insuring what was being done, didn’t do their jobs.

Before the Clinton administration people knew what their jobs were for Glass Steagall made it clear who was to do what.

Long as people used the telephone for business things still got done.

If there was one thing those teachers of the preceding civilization could & did teach, it was how to read and write. In Everything You Know Is Wrong, The Disinformation Guide to Secrets & Lies is the story of US education as written by John Taylor Gatto

“We are producing more and more people who will be dissatisfied because the artificially prolonged time of formal schooling will arouse in them hopes which society cannot fulfill.”

Which means to me you had better keep at your hobby.

Reading comprehension fell from the First World War to the Second World War as tests for recruits showed. Still in general there was the William Shirer era of a real regard for the Life of the Mind, now something to be left behind as soon as one gets a job and hobbies are given up for the television.

And I think to myself we have been living in only 10 years of the smart phone!

The state of things is Meyer Lansky Financial Engineering became the norm, and J. Edgar Hoover national policing themes hang on. The return of Marijuana Policing to the National level by Sessions is more of J. Edgar.

I puzzle at the title of this essay as State Economies Versus Cities unless it means more of the modern means more of the Medieval. Walls were built around Colleges for a reason. The small College, now University Town I came to maturity, adolescence at least was as beautiful as the College, whereas now all the beauty of the town has been sucked out and the University is a movie set image of the university architecture, within its walls.

Of educational systems that I have been in it is the Flight training methods, along with the rest of the learning experience requirements creating a competent certified pilot or mechanic. There is a lot of peer to peer learning that goes on in the cockpit. The culmination of the process for the pilot involves those checkrides. In a pilot’s career it is as they are giving their oral for their doctorate degree continuously. The test primers for all of this are just out there for all to see in question and answers, if you can pass the test you get the certification.

In my country pilot training would be free same as part of public schools & high school driving classes. The Bush Family of politicians was in my life founded by the WWII Navy pilot Bush and the other president the Younger, had been allowed to fly jets.

I am aware Betsy DeVois was involved in educating young students to be pilots. That was said impossible to scale up.

It is not impossible to scale up and a lot of what we see wrong with our world is that some people are jet setters and others, the rest of them aren’t.

I’d be building cheap strong & fast 3 D printed planes if I had any real treasury, like the US still has.

apologies for all the bold print to editor Yves, I had turned it on only for the Disinformation book and I couldn’t get it to go off.