Yves here. Despite Lambert’s daily fear v. greed index reading at super low levels, meaning fear is high, the super tight corporate spreads Wolf discusses below says that there is still a lot of complacency among the investing classes. And note that the pattern he is noticing is abnormal. Risky credit market assets usually sell off months before you see a stock market correction.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street

Market still blows off Fed, Treasury selloff, and volatility in stocks.

Leveraged loans,” extended to junk-rated and highly leveraged companies, are too risky for banks to keep on their books. Banks sell them to loan mutual funds, or they slice-and-dice them into structured Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) and sell them to institutional investors. This way, the banks get the rich fees but slough off the risk to investors, such as asset managers and pension funds.

This has turned into a booming market. Issuance has soared. And given the pandemic chase for yield, the risk premium that investors are demanding to buy the highest rated “tranches” of these CLOs has dropped to the lowest since the Financial Crisis.

Mass Mutual’s investment subsidiary, Barings, has packaged leveraged loans into a $517-million CLO that is sold in “tranches” of different risk levels. The least risky tranche is rated AAA. Barings is now selling the AAA-rated tranche to investors priced at a premium of just 99 basis points (0.99 percentage points) over Libor, according to S&P Capital, cited by the Financial Times.

Also this week, New York Life is selling the top-rated tranche of a CLO at a spread of less than 100 basis over Libor. And Palmer Square Asset Management sold a $510-million CLO at a similar premium over Libor.

In the secondary markets, where the CLOs are trading, red-hot demand has already pushed spreads below 100 basis points. These are the lowest risk premiums over Libor since the Financial Crisis.

These floating-rate CLOs are attractive to asset managers in an environment of rising interest rates. If rates rise further, Libor rises in tandem, and investors would be protected against rising rates by the Libor-plus feature of the yields.

Libor has surged in near-parallel with the US three-month Treasury yield and on Monday reached 1.83%. So the yield of Barings CLO was 2.82%. While the Libor-plus structure compensates investors for the risk of rising yields and inflation, it does not compensate investors for credit risk!

These low risk premiums over Libor are part of what constitutes the “financial conditions” that the Fed has been trying to tighten by raising its target range for the federal funds rate and by unwinding QE. It’s supposed to make borrowing a little harder and a little more costly in order to cool off the credit party.

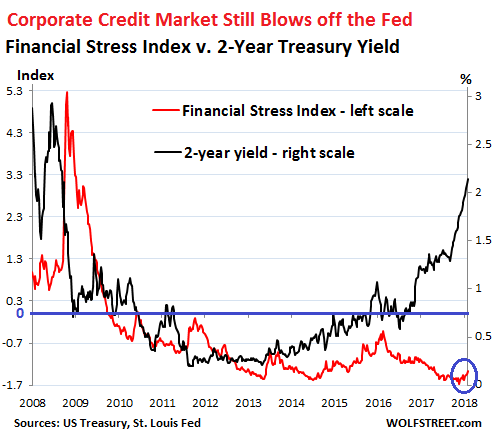

One of the measures that track whether “financial conditions” are getting “easier” or tighter is the weekly St. Louis Fed Financial Stress Index. In this index, zero represents “normal.” A negative number indicates that financial conditions are easier than “normal”; a positive number indicates that they’re tighter than “normal.”

The index, which is made up of 18 components – including six yield spreads, including one based on the 3-month Libor – had dropped to a historic low of -1.6 on November 3, 2017. Despite the Fed’s rate hikes and the accelerating QE Unwind, it has since ticked up only a smidgen and remains firmly in negative territory, at -1.35.

The Financial Stress Index and the two-year Treasury yield usually move roughly in parallel. But since July 2016, about the time the Fed stopped flip-flopping on rate hikes, the two-year yield began rising and more recently spiking, while the Financial Stress Index initially fell.

The chart below shows this disconnect between the St. Louis Fed’s Financial Stress Index (red, left scale) and the two-year Treasury yield (black, right scale). Note the tiny rise of the red line over the past few weeks (circled in blue):

The horizontal blue line marks zero of the Financial Stress Index (left scale). At or above zero is where I — after reading the tea leaves — think the Fed would like to see the index at this point. But the index is far from it. And the CLOs mentioned above are examples of just how ebullient corporate credit markets still are at every level. A similar ebullience is still visible in junk bonds as well.

The corporate credit markets are starting to take into account the risk of slightly higher inflation – hence the appetite for these floating-rate CLOs. But the risk premium over Libor and other risk premiums show that credit markets are still totally in denial about the bigger risk for junk-rated credits: the risk of default. And this risk of default surges when rates rise and financial conditions tighten as these companies have trouble refinancing their debts when they come due. But for now, investors are blithely ignoring that they’re in for a big reset.

The chorus for more rate hikes is getting louder. But no one will be ready for those mortgage rates. Read… Four Rate Hikes in 2018 as US National Debt Will Spike

No doubt correct but as in all things the key is WHEN the reset will occur. We shall see – if history is a guide, it may be a while.

With what I call crackpot fiscal stim headed north of 5 percent of GDP in FY2019, it would pretty tough for the economy to fall into recession absent a massive interest rate or oil price shock.

So junk connoisseurs are not necessarily wrong in accepting them skinny spreads.

Meanwhile the 10-year T-note yield has busted out to a four-year high of 2.90% on a bad (i.e. high) inflation print and trouble in DXY (the dollar index). It’s approaching the three-percent-even Blue Screen of Death line. Have you seen the chart?

Oh my, 3% on 10 year money!

The horror! The horror!

It hurts me too.

With today’s fresh slide, the AGG ETF — a proxy for the Bloomberg Aggregate index of investment grade bonds — has delivered a total return of only 0.86% over the past twelve months, as capital losses owing to rising rates bite hard. Chart [discretion advised; may upset some viewers]:

We’re not far away from the rare event of a bond bear market, defined as less than zero total return. In the past fifty calendar years, there were but four bond bear markets: 1969 (-0.63%); 1994 (-2.92%); 1999 (-0.82%); and 2013 (-2.02%).

When bonds ain’t happy, ain’t nobody happy. :-(

I thought I would add some perspective on the deteriorating underwriting standards in the direct lending space which is effectively a group of middle market lenders that have organized themselves as Business Development Corporations (a type of closed end fund). Reading my brokerage firm’s research analyst on this space, I understand that a group of perhaps a dozen lenders (subsidiaries of pe/ib household names) have been aggressively competing for this business since the middle of 2016 and are reducing both spreads and debt covenants in an effort to win deals. It is clearly a borrower’s market at this point. Also keep in mind that most of the borrowing is by entities that are part of private equity driven M&A transactions where entities are being floated at relatively aggressive debt levels.

Hmm…definitely some “sawtoothiness” to the credit risk line, which tends to get worse more quickly than it improves…

don’t they have to get maximum dopes in at low % and then bust interest rates upward to strip the marks?

or am I paranoid