Yves here. This article describes how the complexity of tasks and level of workforce skills has been falling in US “entrepreneurial” manufacturing companies.

I am sure readers can point to causes. One is that engineering (ex perhaps petroleum engineering) has become less attractive. When I went to business school, about 40% of my classmates had engineering undergraduate degrees and has worked for manufacturing companies. Recent engineering graduates have said in comments that pay levels for college graduates aren’t high enough to justify the cost of the degree; they generally need to get graduate training, like a law degree, to earn an adequate income (and that of course also means working only incidentally as an engineer). Another obvious drain is that mathematicians and physicists have been hoovered up by Wall Street firms and hedge funds since the mid-late 1980s, and more recently, by surveillance state players like Google.

But another factor is the way outsourcing has destroyed skilled blue-collar jobs. One example I’ve mentioned from time to time is furniture. It makes little sense to ship wood from the US or Canada to China for furniture manufacture to have finished or ready-to-assemble goods sent back, yet that is overwhelmingly how we do it. I know an executive from a major you’d-recognize-the-name furniture maker who outsourced their production to China. She said the case was weak, and that for all but the lowest-end furniture manufacturers, you would have done better by investing in just-in-time manufacturing techniques instead. But Wall Street would boost the stock price of companies that announced outsourcing plans, so they went that way instead.

By Meghana Ayyagari, Associate Professor at the School of Business and Elliott School of International Affairs, George Washington University and Vojislav Maksimovic, William A. Longbrake Chair in Finance and Professor of Finance, University of Maryland; Research Affiliate, Snider Center for Entrepreneurship. Originally published at VoxEU

Recent press reports have highlighted the decline of US entrepreneurship. Using data on workers in 800+ occupations in over 1.2 million establishments, this column shows that there has been a decline not only in the number of new businesses in US manufacturing, but also in their size and quality. The proportion of cognitively demanding tasks at new firms has been declining substantially over time, pointing to a process of technological polarisation as incumbents upgrade human capital while entrants focus on low-skilled niches.

Is the US giving up on manufacturing entrepreneurship? Recent business press reports highlight the decline of US entrepreneurship with ominous headlines such as “US economy: Decline of the start-up nation” (Fleming 2016), “Why America stopped being a start-up nation” (Smith 2016), and “A start-up slump is a drag on the economy” (Casselman 2017). Academic research has shown that, indeed, firm start-up rates declined from around 13% in the early 1980s to 10% before the Great Recession and eventually 8% by 2012 (Pugsley and Sahin 2015). This is worrying since young firms are considered to be the engines of growth and job creation in an economy (Adelino et al. 2017, Haltiwanger et al. 2013). Adding insult to injury, the US has long been considered a nation of entrepreneurs, boasting the best financial institutions for young firms to flourish (e.g. Lerner 2002, Kerr and Nanda 2009).

Largely missing from the discussion is an evaluation of whether the decline in entrepreneurship rates is accompanied by a change in the skill type of entrepreneurs, and whether this has long-term consequences. Moreover, a related concern has been the effects of globalisation and foreign competition on US businesses, particular those in manufacturing. In recent contributions, Autor et al. (2013), Pierce and Schott (2016), and Acemoglu et al. (2016) among others, have shown that the effect of foreign competition has been more severe than previously believed. Are these effects particularly severe of new firms?

In a recent paper, we focus specifically on the skillsets of entrepreneurial firms with five or more employees, and how they have changed through time (Ayyagari and Maksimovic 2017). Using over 3 million establishment-occupation-level observations, we seek to answer the following questions:

- How have entry rates and the quality of entrepreneurship changed in manufacturing? Has there been a decline in high-skilled versus low-skilled entrepreneurs, or are entrepreneurship levels declining across all skill types?

- Are there long-term consequences of initial skill at entry – both in the growth rates of entrants and in their subsequent intellectual capital?

- How do entrants’ human capital and growth change in response to competitive trade shocks? How do entrants and incumbents compare in their response?

To examine these questions, we use administrative establishment-level data from the Occupational Employment Statistics by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, which provides employment and wage data on workers in 800+ occupations in over 1.2 million establishments triennially over the period 2005-2013. The Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages further allows us to track the employment outcomes of these firms over time. To measure the firm’s skill-level, we use the Department of Labor’s Occupational Information Network database to order the occupations from low to high levels along the following six dimensions: complex problem solving, non-routine cognitive analytical, routine manual, interacting with computers, offshoring, and probability of computerisation. These six measures capture both the abilities of workers and the nature of tasks in different occupations. We observe each firm’s occupational profile, and are thus able to estimate the firm’s stock of human capital at various points in time along these six dimensions

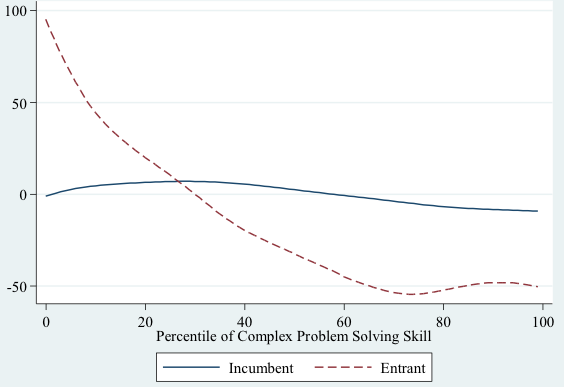

We show that over the 2005-2013 period, there was a decline not only in the number of new businesses in US manufacturing, but also in their size and quality, measured by the tasks which their workforce performs. On the horizontal axis in Figure 1, we plot the average complex problem-solving skills of employees of surveyed establishments, estimated on the basis of their job descriptions (by the Bureau of Labor Statistics) at the beginning of our sample period. On the vertical axis we plot the growth rate of the number of establishments over the period 2005-2013, with separate curves for entrants and incumbent firms. The figure clearly shows that the number of highly skilled entrants fell dramatically over this period, whereas the number of low skilled entrants grew, also dramatically. Changes in the skills of incumbent establishments are much less pronounced.

Figure 1 Changes in number of manufacturing establishments, 2005–2013

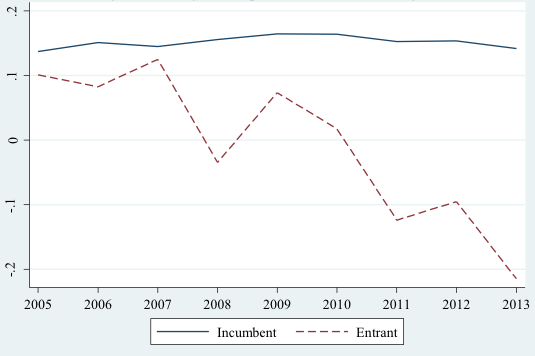

Figure 2 shows that entrants are, on average, performing a higher proportion of routine manual tasks and a lower proportion of tasks that require high cognitive skills, such as complex problem solving. As is evident, incumbent firms do not show the same decline in average skills. We obtain similar differences with locational and industry controls in our preferred regression models. The figure also shows that the differences between incumbents and entrants are growing over time. This has significant long-term consequences – we show that the founding stock of human capital in entrants is predictive of their future human capital as well as growth rates over the early life cycle.

Figure 2 Average complex problem-solving skills

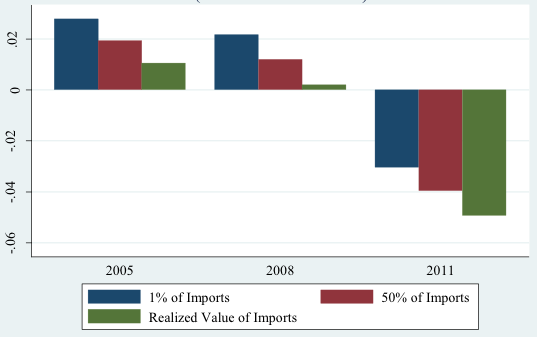

Figure 3 Complex problem-solving skill differences (entrants-incumbents)

The contrast between entrants and incumbents is most stark in their reactions to a competitive threat from Chinese imports. While incumbent firms upgrade their human capital in response to increased competition, the quality of the entrants is minimally affected. As the level of imports increases, more skilled incumbents grow faster than incumbents with lower skills. While these competitive effects on skills are economically significant, the skill differential between entrants and incumbents would exist even with a total cessation in imports, as seen in Figure 3. Thus, the decline in entrepreneurial quality in US manufacturing is only partially responsive to the level of Chinese imports into the country.

Our results are consistent across the measures we use – entrants score lower on skillsets that load heavily on cognitive skills such as complex problem solving and non-routine cognitive analytical, and higher on skillsets such as routine manual, which are more likely to be made obsolete with continuing automation. It is also notable that tasks performed by entrants load heavily on our offshoring measure, in contrast to the incumbents. Only in high-tech manufacturing industries are these effects muted.

At first glance, one might be tempted to view the drop in perceived quality of entrants as a consequence of new technologies adopted by entrants optimally requiring a less-skilled workforce. While we cannot rule this out, it is unlikely to be the case given that new establishments created by incumbent firms, which are likely to be better funded and able to acquire new technologies, do not show similar deskilling.

Our findings are consistent with technological polarisation, whereby incumbent firms upgrade their human capital, and entrepreneurial firms are finding investment opportunities in niches employing less skilled labour. There is some evidence in our paper to suggest that incumbents are becoming less engaged in routine manual tasks, which are being taken up in greater numbers by entrants. This polarisation is particularly stark in industries facing import competition where incumbents are upgrading their human capital most, both in their legacy plants and in the new plants they construct. One ray of sunshine is that the polarisation is much less evident in high tech industries.

See original post for references

Another aspect – I don’t know whether this has been studied in the US – has been identified by the development economist Ha Joon Chang. He has noted that as manufacturing jobs become less certain there is a measurable tendency for parents to steer their more talented children to ‘safe’ professions like medicine or law rather than engineering. He did a few studies in Asia – South Korea in particular – where this was observable when labour markets became more deregulated from the 1980’s onward and traditional ‘jobs for life’ type corporations faded away. The result is an economy with an excess of highly intelligent lawyers and doctors and mediocre engineers (something observable in many developing countries). In contrast, countries like Germany and Switzerland encourage their best and brightest into engineering, mostly by the simple expedient of ensuring a healthy supply of secure well paid engineering work.

I think there is also a class aspect to it – I recall many years ago reading a series of articles by a British engineer who’d worked around the world. He said one crucial thing he noticed was that in the English world there was a social tendency to look down on the skilled technician as ‘just’ a factory worker, whereas in successful engineering countries like Germany it was seen as a respectable profession. I think someone expressed it here by the joke that when in England or the US someone introduces themselves as an engineer, people say ‘hey, my fridge is broken, can you look at it?’ In Germany they say ‘hey, have you met my daughter?’

Interesting point.

When I worked in high tech manufacturing in the early 90’s, (in the US) we had two tech’s that were highly skilled in soldering tight tolerance RF components. The production work was always backlogged because the engineers constantly had a flow of prototype work that they wouldn’t trust themselves to do. The solder flow had to be perfect because the amount of solder would effect the overall tolerance of the product, and the expensive (and hard to get) components were highly susceptible to heat damage. And every year the floor lead for that area had to fight for wage increases as it was one of the lowest paid areas in the shop. Techs that basically sat in front of screens testing software all day would make 30-40% more.

His biggest advocates were often the Engineering leads, who carried a lot of clout.

When there is no appreciation for quality work, you’re not likely to get much of it.

Yes, I agree that in the Anglo world, especially in the US and the UK, manufacturing is seen as low class, for lack of a better term.

Things are different in some areas, most notably the Midwest.

However, as a whole you can see this attitude, particularly in the wealthy coastal cities. Note the dismissive attitude of the Clinton base towards manufacturing for example during the 2016 election.

In truth, manufacturing is very much a knowledge profession and certainly more productive than say, the current financial sector.

I think that in the coming decades, when the extent of the US decline becomes apparent, it will be clear to the world that the US is as ideologically attached to capitalism as the USSR was to its ideology. Like the Soviets, America’s biggest problem will be its extractive elites.

Parts of the Midwest were heavily settled by German immigrants. Could that pro-engineering attitude in the Midwest be in part a legacy German attitude?

The best engineering in the world won’t help your startup unless you can find a skilled machine shop, and they are disappearing quickly as the machinists retire and their children stare into their phones. It doesn’t help that trades aren’t learned in high school (actually discouraged) and a nice 5 figure sum is needed to get the training to use a 5-axis milling machine for which a starting wage is $15/hour.

And no, 3D printing is not the answer. It still takes a skilled machinist to clean up a laser-sintered metal part.

Machine shops pay crap money. There is no market signal. The signal is distorted by international trade cos there is no shortage of Chinese technicians.

Ding! A young friend of mine, young enough to be my grandson, really bright and personable young man, went back to a highly-regarded tech school to be a machinist, CNC and all that. After two years in school he got hired right away but at minimum wage, which he is still making a year later, and he has a two-hour commute twice a day.

This sort of thing cannot end well.

About 15 years ago while working for a consulting firm, I worked on a project for a local organization that was made up of small and medium sized manufacturing firms. The organization was trying to increase the local talent pool of engineers to support the employment needs of these small and medium sized manufacturing firms. The core of the problem was that these manufacturers were running so lean that they couldn’t hire entry level engineers (or so they believed). They needed engineers with at least a few years of real job experience. In years past there were lots of manufacturing facilities in town owned by large corporate manufacturers that hired engineers out of college by the droves. Some would stick around and work for them for decades while others were leave for these smaller firms after a few years. Once all of those large manufacturing plants were closed they lost their source of job-trained engineers. I can imagine as more and more plants across the nation closed this problem spread. Add on top of it ever increasing amounts of fear over jobs and family finances, even in towns with large corporate manufacturing facilities, who would want to go to work for a start-up that might not be there in 5 years. And if you stay with the large corporate manufacturer, as an engineer you probably would be offer the opportunity to transfer if the existing plant was closed.

bingo! that’s a huge one.

Another related one is US industrial firms’ relationship to skilled labor and professional tech staff- that is, complete fear of a possible outcome where the labor and tech staff, and the management become dependent on each other for financial security.

As a result, operations and design/build flow are structured to move skilled work outside the firm. Typically embodied in purchased modules (which is a trend anyway, but encouraged by the labor dynamic). In manufacturing itself, most of the skilled labor is embodied in imported automation tooling and specialty machines and subsystems. And in the past decade, also fabrication of in-house designed electronics and in-house designed mechanical components too. The notable exceptions I think are software and moldmaking.

Within manufacturing, the domestic tech work is increasingly routine layout type work and interconnection of complex purchased modules, which are moving to the “black-box” style. In domestic manufacturing (in contrast to design), more of what remains is 2-year tech school work, while highly specialized value added becomes embodied in the imported subsystems.

I got a kick out being called “stawk of human capital”. It’s so personal.

Hmmm. I wonder if economists would choose their field to work in if all of a sudden their competition didn’t come from across town, but from a place far away charging one fortieth of the normal going rate?

Lots of people wonder about that. Dean Baker is always pointing out how our professionals such as doctors and lawyers have their incomes protected by legal restrictions on competition while ordinary people have to sink or swim in a highly competitive, high unemployment environment. Since Wall Street seems to be controlling the country’s economic policy perhaps we should just move the capital from DC to NY and be done with it.

Where I live there is an effort to train more skilled blue collar workers to service the work of engineers who live elsewhere. The region was once covered up with textile mills (owned by tycoons from up North) but they are almost all gone and our county now sports BMW’s largest assembly plant instead. Not only are the engineers in far away Germany but I believe the engines–the highest value added part of the cars–all come from there as well. For awhile my father worked for a company that supplied machinery to those textile mills. Now the building where he worked is an empty shell like the mills themselves.

Yea! Let’s hear it for comparative advantage!

As a teenager (18) I found a job road testing BSA motorcycles then a year later moved to Norton,s. British bikes ruled the world back then, except for BMW in the sidecar class. The designer were up to date with 4 valve heads and overhead cams back in the 40’s. The management sat on it as the push rod twins were still in demand, tweaking the line year after year. for the 1071 year the Triumph designers came up with oil in the frame (who cares) but ignored the fact that seat height increased to the point that the average rider could not put both feet on the ground. the product crashed costing the company hundreds of thousands of pounds, which added to an already heavy debt was the start of the end. Even the Duke of Edinburgh laid the blame on management for the demise of the industry.

Working in the automotive industry, you are correct. The highest value parts come from their home nations.

The manufacturing of manufacturing tools like Stamping presses, robots, and other key capital goods comes from the home nation. So too do the designs of the vehicles. So too is the most important R&D work.

America is becoming a branch office economy.

I am on my phone, but Eamonn Fingleton, the Irish journalist has a solid record for predicting this type of thing and he noted that the most valuable parts of a car are coming from abroad.

Even our domestic manufacturers, the big 3 US automotive companies are dependent on other nations. Why? The US no longer leads in robotics and capital goods.

Economists are not paid what they are paid because they are in short supply or there is a lack of foreign competition. They are paid what they are paid because that gives credence to the whole story about “human capital” and “wages=productivity,” which anyone can see is complete nonsense if, but only if, they are able to cut through the noise of millions of economists proclaiming its validity.

I never understood why an acquaintance, who has a job with a large bank, was hired as an ‘economist’ when all he does is parrot what his upper management tells him. What he says in social situations about ‘the market’ and how to approach it is nearly always wrong for the average person. You’ve provided insight. He makes six figures so I’ll start thinking of his ‘expertise’ as merely flak. It simply never occurred to me what useful function he might have, because I otherwise couldn’t see one.

As Fernand Braudel pointed out, capitalists hate ‘the market’ and rely on the government to control it or squelch it. And, as we saw in the 2008 crash, bail them out with tax money. And they need ‘noise’ to distract. There never was competitive advantage moving manufacturing out of the country or overseas. It was all about profit, money that went to very upper echelon.

One of the ways the US won WWII was our huge manufacturing sector.

We are screwed on so many levels.

If we had a government who gave a dam, they would demand warranty periods of ten years for large appliances, since they used to last decades in the 60’s 70’s. Now its until you get it over the step at the front door. being a Luddite at heart, i still yearn for the days when we fixed things rather than throw stuff away because its old, often before it even gives trouble. Being working class in the UK within a few doors of where you lived, someone had a chimney brush, another had a last for boot repairs etc we borrowed and lent to keep costs down. Now 60 years later I rebuild old motorcycles for a hobby. . .

I just had to replace a SIX year old GE washing machine where the agitator mechanism had completely corroded. (About 1/4 of the large, cone-shaped piece attaching the agitator to the rest of the machine was completely gone.) Stupid me for thinking that because the tub was stainless, the major parts underneath it would also be corrosion resistant.

It’s getting harder and harder to justify buying domestic.

Are you sure your GE washing machine was domestic? I thought the GE name went along with some of the companies GE divested when they failed to meet Neutron Jack’s demands on returns.

GE sold its washing machine division to Haier but my machine was still manufactured (assembled?) in Louisville.

This looks like a result of bad design, which is domestic according to GE website. Incidentally, I had exactly the same failure of my GE washer about 10 years ago.

Correct me if I am wrong but would not the long term effect of this be to reduce the number of qualified American engineers? Trump talks about a huge infrastructure project but would there be enough qualified engineers to carry out all the required work? Would that not mean that as time goes by, America may not have the technical capability of building sophisticated projects and would have to bring in outside teams?

I seem to recall during the 2008 crash that at that stage, somebody said that America was turning out more software engineers than real engineers. Kinda weird as from my reading, if there was one thing that America was famous for it was its engineering ability. That meant everything from Hoover Dam through to the Moon landings. America even once produced a TV series about a man that had a great talent for engineering – MacGyver – and I could not see that series being made in any other country. OK, well maybe Germany!

> “She said the case was weak, and that for all but the lowest-end furniture manufacturers, you would have done better by investing in just-in-time manufacturing techniques instead. But Wall Street would boost the stock price of companies that announced outsourcing plans, so they went that way instead.”

IMO, this captures a seminal cause of “suckifying” quality. Disrupting the synergy between design and manufacturing by disrupting the funding, and disrupting the feedback.

…the neoliberal project has a seeming affinity for spouting words like “efficiency” but never compelled to clarify the context, eg, accumulation(concentration) v. distribution (seeding or feeding) etc…and conflating the real with the virtual, making any clarity, esoteric by ‘design’.

Skilled machinists make lots of money. That is the career I would recommend to any young person.

Second, is plumber. $100+ an hour around here.

Meanwhile, law school graduates with hundreds of thousands of dollars in student debt are working for $20 an hour and thanks to Joe Biden, are shackled to their debt for life.

Q: What do you call a 50 year old engineer?

A: Unemployed.

Engineering degrees supposedly command the highest starting salaries.

That was true when my father went into the chemical engineering field during the early 1950s. But Dad’s career hit a flat spot because he just plumb wasn’t the managerial type. He was a researcher, through and through.

Engineering degrees supposedly command the highest starting salaries:

1. The career longevity is only good if one transitions to management or consulting.

2. Over Doctors? Dentists? Finance?

Oh really!

To start a manufacturing firm you need a product that fills a special niche and a market for that product. Unless you can protect your product with a patent or through trade secrecy you can almost count on someone copying your product if you really have a market for it. Best to have a trade secret and remember the old pirate wisdom about keeping secrets. To identify the special niche and construct a product to fill it you need much more than an engineering degree. You need to know the problems your market needs solutions for — often you need an insider’s knowledge of the businesses. You need to know what competing products there are and what they cost. Ever been to a trade fair for production machinery? The numbers and sophistication of devices, techniques and mechanisms are legion, and prices are only available if you appear you might be an actual buyer. If you craft a product and identify a market for it you need to gain entry to that market. For retail markets you will probably find yourself paying for shelf placement, or trying to get an appointment with the buyer for a chain of retail outlets. For industrial sales you might have to buy space in one of the trade fairs and hope you get noticed. And what about the money required to support all these undertakings as you fight your way into the marketplace, and the management skills to organize people and execute plans? None of these things are taught in engineering schools and the people who are interested in engineering are often not too interested in management and finance and marketing and sales. The training an engineer receives in a bachelor’s program bears little relation with the kinds of real world problems that engineer might face as an entrepreneur. For that matter the university training of an engineer seldom touches on the practical problems which arise in actually building or manufacturing something. The undergraduate generalities are insufficient and the graduate school specializations too particular to be of use on their own in the real world. An important part of being an engineer is learned on the job with hands on real tools and materials. The firms which once provided this finishing training have closed their doors or left our shores long ago. To my thinking the wonder is not that we have few and fewer entrepreneurs in manufacturing — at any level of skill or sophistication — but rather that we have any at al

If one is going to be a small manufacture, manufacturer of parts or components, than one needs the bigger manufacturer/assemblers to be one’s customers.

As manufacturing moved out of the US, so did the smaller component suppliers, as did most of the supply chain.

Something about Ross Perot, the 1992 Presidential election, and “giant sucking sound” nudges my memory.

I don’t see this changing any time in the near future.

My view has always been that a developed nation without serious manufacturing won’t remain a developed nation for much longer.

The German Mittelstand is an example of what can be done.

http://www.bbc.com/news/business-40796571

It’s not just the big companies that make the difference – there need to be Anglo Mittelstands too. That won’t happen without a serious industrial policy, a weaker USD, and a cultural change – manufacturing has to be given the respect it deserves.

Given the neoliberals in charge, I’m not holding my breath.

Decline of manufacturing is tightly tied to the state of R&D and other serious, compounding, and not often discussed issues:

A major cause: Many companies laid off R&D to spend all their money artificially inflating their stock price by buying back their own stock. Next, they outsource manufacturing. Labor is only 11% of manufactured cost. The savings in outsourcing is short term, and is more in plant and equipment. This is reflected in the poor state of capital investment. The net result is that we have lost our supply chain, along with the whole ecosystem of business to business deals among parts suppliers,assemblers, and skilled staff.

Then, there is a nasty combination of contract law and litigation risk. It is easier to threaten to sue suppliers than pay what they are owned.

Finally, the most important root of productivity is invention. Inventors are an endangered species, because, due to the above lack of corporate R&D staff, they lack business to business deals to sell their ideas to, and, very importantly, exist at the risk of predatory litigation. This is no laughing matter, and, is in fact how business is done in America. Look at our president. The role of academia in innovation is also often very unhelpful. Academic publications of late rarely if at all cite patents. That is an entire, very cite-able literature. Failure to cite these wrongly sets up academia as the sole source of innovation, AND cuts them off from industry, AND, obscures what is most important; the true state of the art. Academics that sit on research boards therefore often do not know what they are doing. The Bayh Doyle act is what turned Universities into patent mills in competition with private inventors. Granting agencies require 50% matching funds from small business, but, not from Universities. That is not a good thing, because the know how often exists outside these institutions.

All the above has to do with ethics, fair dealing, and common sense, which appears to be lacking.