By Giorgio Barba Navaretti, Professor of Economics at the University of Milan, Giacomo Calzolari, Professor of Economics, Bologna University and Alberto Pozzolo, Professor of Economics at the University of Molise. Originally published at VoxEU

Financial technology companies have spurred innovation in financial services while fostering competition amongst incumbent players. This column argues that although incumbents face rising competitive pressure, they are unlikely to be fully replaced by FinTechs in many of their key functions. Traditional banks will adapt to technological innovations, and the scope for regulatory arbitrage will decline.

FinTech hype abounds. In the news, financial technology is described as “disruptive”, “revolutionary”, and armed with “digital weapons” that will “tear down” barriers and traditional financial institutions (World Economic Forum 2017).

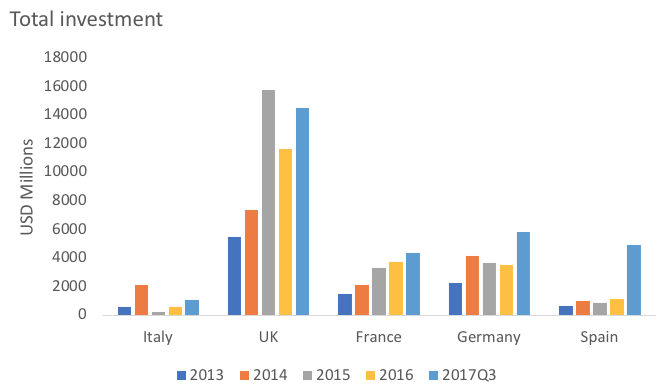

Although investments in FinTech have been expanding very rapidly in financial markets (see Figure 1), their potential impact on banks and financial institutions is still far from clear. The tension between stability and competition underlies the entire debate over FinTech and how to regulate it. The crucial questions are whether and to what degree FinTech companies are replacing banks and other incumbent financial institutions, and whether, in doing so, they will induce a healthy competitive process, enhancing efficiency in a market with high entry barriers, or rather cause disruption and financial instability. Our editorial in the new issue of European Economy deals especially with the relationship between FinTech and banks (Navaretti et al. 2017).

Figure 1 Investment in FinTech companies is increasing in all major European countries although there is much cross-country heterogeneity

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on data from CBInsights. Value of total investment in FinTech companies in each year; data for 2017 refer to the first three quarters only.

We argue that FinTech companies enhance competition in financial markets, provide services that traditional financial institutions do (albeit more efficiently), and widen the pool of users of such services. In most cases, FinTech companies provide a more efficient way to do the same old things that banks did for centuries. But it is unlikely that FinTech will fully replace traditional financial intermediaries in most of their key functions, because banks are also well placed to adopt technological innovations and themselves perform old functions in new ways.

FinTech companies mostly provide the same services as banks, but in a different and unbundled way. For example, like banks, crowdfunding platforms transform savings into loans and investments. But unlike banks, the information they use is based on big data rather than on long-term relationships; access to services is decentralised through internet platforms; risk and maturity transformation is not carried out as lenders and borrowers (or investors and investment opportunities) are matched directly. There is disintermediation in these cases. However, such pure FinTech unbundled activities have limited scope. For example, it is difficult for platforms to offer clients diversified investment opportunities without keeping part of the risk on their books or otherwise securitising loan portfolios. And it is impossible for them to benefit from maturity and liquidity transformation, as banks do.

Other functions carried out by FinTech companies, such as payment systems (e.g. Apple Pay instead of credit cards), are still supported by banks. Banks lose part of their margins but keep the final interface with their clients, and because of the efficiency of these new systems, they may well expand their range of activities. In such cases, there may be strong complementarities between banks and FinTech companies.

In general, the value chain of banks includes many bundled services and activities. FinTech companies generally focus on one or a few of these activities in an unbundled way. Nonetheless, bundling provides powerful economies of scope. The economics of banking is precisely based on the ability of banks to bundle services like deposits, payments, lending, etc. For this reason, FinTechs will also have to bundle several services if they wish to expand their activities (e.g. for the crowdfunding example above) or integrate their services with those of banks (e.g. for the payment systems described above).

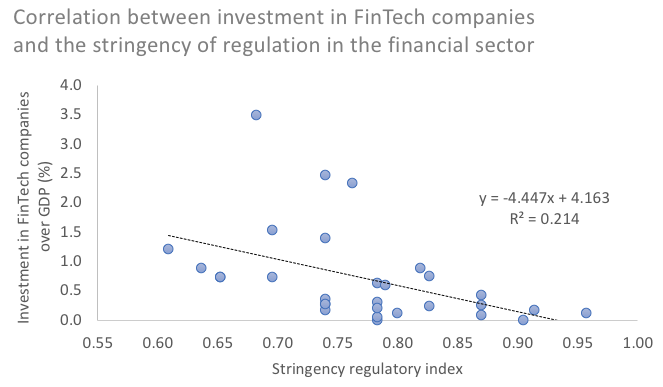

The business model of FinTech companies, therefore, is very likely to gradually converge towards that of banks. As this happens, it is no longer clear that FinTech companies have a neat competitive advantage over banks, apart from the legacy costs that banks face in reorganising their business. Moreover, as FinTech companies expand their range of activities, the scope for regulatory arbitrage – which the much lighter regulation of their activities has granted them so far – will surely decline. Figure 2 shows a negative correlation between the stringency of regulation and the size of investment in FinTech companies. We argue that a case by case regulatory approach should be implemented, essentially applying existing regulations on FinTech companies, based on the services they perform. Regulation should be applied when services are offered (of course with an element of proportionality), independently of which institution is carrying them out.

For example, if we consider again loan-based crowdfunding, different regulatory frameworks could be relevant, depending on what these platforms actually do. Banking regulation could be unnecessary if the platforms do not have the opaqueness of banks in transforming risks and maturities, and do not keep such risks on their balance sheets – for example by collecting deposits and lending outside a peer-to-peer framework. But it should be enforced if platforms carry out such activities. In general, we need to avoid a situation where FinTech companies becoming the new shadow banks of the next financial crisis.

Figure 2 Investment in FinTech companies in European countries declines with the stringency of financial regulation

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on data from CBInsights and the World Bank’s Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey. Funding FinTech over GDP (%) is the share of outstanding amounts of investment in venture capital, corporate venture capital, private equity, angel investment, and other investment over GDP. The stringency regulatory index is constructed using 18 indicators from the World Bank’s Bank Regulation and Supervision Survey.

Once regulatory arbitrage is ruled out and the same regulatory framework is imposed on all institutions based on the functions they perform, the playing field is levelled. Then the only competitive advantage is the one granted by technology and the organisation of activities. The framework becomes one of pure competition with technological innovation.

Convergence is not new in digital industries. Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and even Microsoft all started in different types of businesses (retail, computers and phones, social network, search, and software), but they are now converging to a similar set of activities that mix all the initial areas of specialisation. Interestingly, most of these conglomerates have already experimented with entry into the financial services sector, although without great success to date. However, we may expect more of this in the future. These large firms have cash, they have huge volumes of personal data, and their business models are largely based on matching consumers to their needs and network externalities that tend to generate winner-take-all outcomes.

Digital innovators have been hugely disruptive in many sectors. Netflix caused the ‘bust’ of Blockbuster, and Amazon had a similar effect on many retailers and booksellers. Skype took 40% of the international call market in less than ten years. For incumbents, the deadly mix that these newcomers presented consisted of lower-costs and higher efficiency, plus better or new products and services, combined with the incumbents’ own inability to swiftly adapt to the changing landscape.

But although evocative, these examples don’t precisely fit the financial industry, because banking is a multiproduct business with largely heterogeneous customers, and it is intrinsically plagued by asymmetric information and heavy regulations.

Competition will enhance efficiency and bring in new players, but it will also strengthen the resilient incumbents, those capable of taking on new challenges and playing the new game. Intermediation will partly be carried out in a different way than today— more internet and internet platforms, plus more processing of hard information through big data. But intermediation will remain a crucial function of financial markets. Banks will not disappear. If some do, they will be replaced by other, more efficient ones. The real casualties will not be banking activities, but inefficient (and possibly smaller) banks and banking jobs.

See original post for references

Just a few random observations about how FinTech may work out though I am not up on it at all. I am guessing that the first thing would be the loss of millions of bank employee’s jobs but as those people aren’t really important then there is no loss here as far as Silicon Valley is concerned. The denizens of that place will be even more in demand because of FinTech so, no problem. This is called disruption but not for those living in Silicon Valley.

I would guess that block-chain would be a key underpinning technology for it but has anybody done any back-of-the-envelope calculations on how many server farms would be needed, how much bandwidth required, and last but not least – how much power that this would be all requiring? It would have to be a colossal amount by my guesstimate so they may want to start working on zero point modules right now.

I have heard that these mobs want to use an artificial intelligence interface to increase automation but truth be told, AI is nowhere near capable of being deployed in the real world. It won’t stop them from doing it but it is still not ready nonetheless. Then there is the factor of all this data which will be capable of being monetized, privacy be damned. Do you trust Silicon Valley with all the info of your financial transactions? I thought not. Certainly the world’s security services would be plugged into all these transactions.

Finally there is one factor that I believe may be at the heart of FinTech and that is why. Yves, I believe, has said that whoever writes the contract gets to control the negotiation. This thought has led me to believe that eventually there will be a propriety set of software applications and technologies to make this FinTech possible (Apple Pay as an example) and Silicon Valley wants to have a throttle-hold on this and thus gets to shape future modern finance. They will be the ultimate gate-keepers of modern finance if not robber barons. They would be the ultimate rentiers.

There aren’t millions of jobs at issue here. Payment processing is already plenty automated, and “FinTech” is playing pretty much entirely there. This is more about squeezing margins in certain spots by having new players come in and take a cut. Banks will push back and regain some (often a lot) of ground by introducing their own apps. They will be particularly motivated because fees plus they want to own the customer as much as possible.

I hope Clive will pipe up and elaborate and qualify to the extent that needs to happen.

You are right that Silicon Valley WANTS to be the gate-keepers, but owning the back end and having licenses and controlling the payment systems plumbing, which these other players really cannot circumvent, is a big check. PayPal has made inroads, and look at what is happening to them. First, they are subject to more and more banking reg requirement. Second, their biggest customer, eBay, is abandoning them, presumably over their fees (as bad as Mastercard/Visa) and not bothering to upgrade their services much/at all. As readers know, NC uses PayPal reluctantly only because it offers payment processing without the nasty monthly minimum requirement of getting bank merchant accounts. That is PayPal’s big hook. Some other companies have offered similar services (we used WePay) but went by the wayside when they started asking for monthly minimum transactions volumes well over what we were getting from readers.

My kids use Venmo in their circles, and there appears to be a business component, too. Is that an option for your business?

Btw, more money on the way to you. Thank you and your team for all that you do.

Venmo is owned by PayPal.

Should have made my comment clearer when I posted last night. My assumption here was that FinTech would seek to get rid of as many brick-and-mortar branches branches as possible and have it nearly all done via mobiles, tablets, etc. Add up the number of bank branche employees worldwide and that would have to run into perhaps a million or two.

When eBay officially splits from PayPal in 2020 they will be using some mob called Adven which apparently is an Netherlands based financial processing company. Will that be a possible option for NC as well?

Brilliant description of the issue.

And I’m, willing to bet that any transaction which needs such system will not incur a transaction fee of $0.01.

Sic Transit Gloria.

Lambert has already posted a tweetstorm by a highly regarded tech guy that I have to dig up again. He says there are zero indications that blockchain is going anywhere as a tech. No people in companies doing secret projects with funds and staffing carved out of other budgets. No techies developing ideas in a serious way for VCs (hype is another matter). I’ll see if I can get him to give me the link. It was recent and very damning

Hi thanks, I think the article assembles a lot of useful ideas in one place. I’d like to quote an important stepping stone in the article,

and say that there seems to have been a trend in IT-is-innovatory-and-efficient service delivery rational that misses that IT is also backed by large continuous investment & high stock prices. We should understand more about what the actual ‘innovations’ and ‘efficiencies’ I.e. actual change that is brought about by IT, and now that we’ve experienced Uber, Netflix, Amazon, Google, Microsoft etc, understand how their practices have made simple before and after comparison questionable without comprehensive economic, social & political analysis. A small point might be that an article appeared recently that argued that the electronic health record was not more efficient, which strikes at the truth of one of the most persistent long term claims (shibboleths?) made by the IT industry, business & academia over the last 20 at least years.

It’s time to review and ask what (amongst the share buy backs, tax breaks, oligopolies, capital/ponzi-appearing profit accounting) what the machinery of IT actually gives us. Yes—for financial serves too. In some instances the tech is merely a database and web forms mixed with maps and other people’s resources like cars and drivers as in Uber (—did Yves make this point recently? Certainly this website has been tracking all of these companies and their products and includes discussion of their claims to innovation & aspect of their wider social significance I feel. How about collateral damage?).

An interesting for me question to end on is that of IT and productivity. In the book “The Rise and Fall of American Growth” the author I think makes the point that economists have been looking for evidence of long term increases in productivity due to IT, beyond about 7 years associated with a period of relatively intense deployment, but so far this has not been found. I’m going to drop into this response a pointer to Steve Keen’s recent work on production functions and energy—production functions also being part of Rise and Fall’s approach to productivity measurement—and say I’ve hit my limits tho I’m a very interested amateur. I think questions of ‘productivity’ must be one of the very broad discussion areas about the direction technology and economy are taking (particularly in finance, given the nature of money that’s hated by most mainstream economists) in our world of finite resources, energy efficiency without fossil, climate change, vested interests, and inequality.

Jim

Hi again

Sorry, I forgot to repeat the kind of point made by others elsewhere, that IT offers powerful functionality, tho may simply now be being used to ‘bomb’ the competition by means of the huge payload of financial resources that are used to back it.

Jim

Anyone can build IT systems.

The real barrier to entry is gaining customers. The “go to market” issue.

In a software business, 7-12% is engineering 55% GS&A, the remainder is profit.

Of the 55%, 5% is G and A, 50% S.

General

Administration

Sales – sales is expensive.

This post impresses me as remarkably glib. Just the usage of a construct like ‘FinTech’ makes me wary of the verbiage to follow.

“FinTech companies enhance competition” and the existing banking and finance regulations are fine and should be applied to FinTech on a case-by-case basis depending on the services they provide. Banks are becoming like FinTechs and FinTechs are becoming like banks and banks will still be around. But I guess “inefficient (and possibly smaller) banks and banking jobs” might be in trouble. But don’t worry everything is fine and just getting better — more competitive and more efficient.

This post presents a cheery view of the likes of “Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and even Microsoft” characterized as “digital innovators”, “hugely disruptive” bringing “lower-costs and higher efficiency, plus better or new products and services”. Who knows what wonders big data, more Internet and Internet platforms might bring to the financial industry which is “intrinsically plagued by asymmetric information and heavy regulations”? I don’t look forward to John Galt running the banks using AI to mine big data and married with big platforms and more aps. Call me a Luddite but I’d rather deal with George Bailey.

I don’t like being a heavy, but you seem not to have read the article, which is violation of our written site Policies. The authors were clear that tech cos are not going to replace banks.

They didn’t hammer on core point: no one is going to have large intra-day balances between players without having a central bank backstop. You don’t get that unless you are a bank and not just any bank at that, you have to submit to a ton of regulation and oversight. Tech cos won’t want to go there. They will be happy cherry-pikcing and extending their brand reach a bit.

I may have misunderstood this post but in fact I read it several times. Each quoted section of text in my comment is pulled from a section of the post. I view a company like Amazon as a new form of monopoly construct. Embedding a payment mechanism seems — to me — a natural extension of Amazon’s monopoly construct. Amazon is embracing warehousing, and delivery services, and it seems plausible to me that it might add a payments construct with or without some bank in the middle. Will that payments construct be classified and regulated as an element of banking — certainly not if Amazon has its way. I agree with you that Amazon and the other tech cos will not replace banks and have not shown any interest in replacing banks. But I think the post can easily be read as equivocal on that point.

The post indicates “Once regulatory arbitrage is ruled out and the same regulatory framework is imposed on all institutions based on the functions they perform, the playing field is leveled. Then the only competitive advantage is the one granted by technology and the organization of activities. The framework becomes one of pure competition with technological innovation.” At its tail this post states “But intermediation will remain a crucial function of financial markets. Banks will not disappear.” If a FinTech provides some services like a bank — when does it become a bank? If a bank adopts technologies like a FinTech to provide services — is it a bank or a FinTech? Could a bank buy some big data or aps from a FinTech or buy or control or cooperate with a FinTech to obtain its big data to intermediate the provision of banking services and link those with the FinTech’s marketing platform? FinTechs may never want to be banks but do banks regard FinTechs with similar disdain?

I think the post’s core point was that no further regulation of FinTech banking practices was necessary if the existing banking regulations were applied to FinTech services that are like banking services. I don’t agree with that position. And I don’t agree that the finance industry including banks is “plagued by … heavy regulation”. I believe finance regulations should be bolstered and constructs like Amazon and Google et al should be regulated to constrain their growing power in the economy. I am not comfortable that existing bank and anti-trust regulations are enforced or that if they were enforced that they would be adequate to prevent a FinTech and a bank from operating together in arrangements just shy of provable collusion. I believe such a construct could create a powerful form of vertical monopoly.

Hopefully there are antitrust prohibitions and business considerations that present insurmountable barriers to mergers and acquisitions between and by large fintech companies and large banks.

FinTech cos would never want to be banks. Lower earnings multiples, lower margins due to more regulation, more exposure to consumer litigation.