Yves here. One issue with supply-side restrictions is that they are designed to limit use by making fossil fuels more costly and/or scarce. The costs of that will fall most heavily on the poor in the absence of mitigating policies. But then again, so too will the damaging effects of climate change.

By Gaius Publius, a professional writer living on the West Coast of the United States and frequent contributor to DownWithTyranny, digby, Truthout, and Naked Capitalism. Follow him on Twitter @Gaius_Publius, Tumblr and Facebook. GP article archive here. Originally published at DownWithTyranny

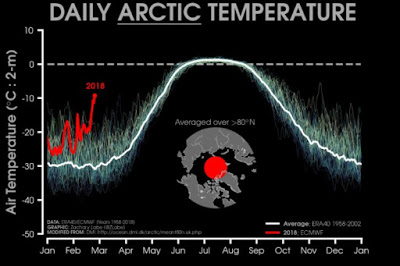

Daily average Arctic surface temperature since 1958. The red line is now — 2018 year-to-date (source: Bill McKibben).

Climate policy recommendations, to date, cluster around a very small number of recommendations, all designed to discourage demand for fossil fuels and encourage demand for renewable energy sources. Few policy recommendations address the plentiful, cheap and growing supply of fossil fuels.

This is a major mistake. It may even prove fatal to the great task ahead. And only the climate activist and policy community can fix this error.

Consider the following six points.

The Argument for Restricting the Supply of Fossil Fuels

1. Note the graph above. If it’s not already clear that global warming has not just reached truly dangerous proportions, but is accelerating, what’s shown in graphs like that should dispel all doubt.

Here’s another, from the same series of tweets by climate writer Bill McKibben:

Hmm, something seems a little different this year when it comes to ice in the Bering Sea pic.twitter.com/RwCayhinmt

— Bill McKibben (@billmckibben) February 25, 2018

The Chukchi Sea is the region of the Arctic north of the Bering Strait. As you can see, the extent of sea ice is declining precipitously. (See also here and here.) All those tiny lines are measurements from the most recent previous years.

(Both of these graphs come from the website of climate scientist and student Zachary Labe, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Earth System Science at UC Irvine. The site is rich in graphs like these. For more Arctic sea ice figures, see here and also the links at the bottom of the page.)

If this isn’t an emergency, what is? The World War II analogy would be: Germany has been arming for war for years and has now massed troops on the Polish border. There’s no time to waste in preparing the Polish people for the onslaught.

2. If there’s no time to waste in addressing the climate crisis, it’s necessary not just to restrict the demand for fossil fuels — for example, via carbon taxes and mandatory emissions standards — but also the supply.

This means, in turn, putting the squeeze on the economy to force a conversion to renewable energy supply, rather than simply put pressure on the economy via more gentle restrictions and encouragements that allow the economy to adjust, if it wishes, in a way that’s “comfortable.”

Examples of “comfortable” demand restrictions include carbon taxes and mandatory cap-and-trade systems. “Comfortable” demand encouragements include subsidies for renewable energy infrastructure.

Supply restrictions, in contrast, tend to be uncomfortable — for consumers because supply is restricted in advance of changes in buying behavior or availability of alternatives; for suppliers because the flow of profit is artificially constrained; and for segments of the economy as a whole because money is forced out of fully operating sectors (fossil fuel production, delivery and use) and into alternative, less-developed areas.

The purpose of supply restrictions, in fact, is to use that discomfort to force changes in behavior, to force the development of alternatives — and not to settle for waiting until the market or consumers decide to make these changes on their own.

The World War II analogy would be the transfer of money from the consumer part of the U.S. economy via rationing into the war-making part of the economy, in order to force the production of ships, tanks, guns and other materiel needed by the military. The constricting factor, the reason the U.S. couldn’t support both parts of the economy at full capacity, is manufacturing capacity. No developed nation can double manufacturing capacity in a year, even with all the money in the world to do it. Capacity to make cars, for example, had to be converted to make tanks. In the same way, overall spending had to be diverted, since a nation’s ability to expand government spending, while large, isn’t infinite.

3. Restrictions on supply, when coupled with constrictions on demand, work very well in other areas where public policy intervention is needed to create a positive social change. Consider the attempt to limit tobacco use in Australia, from a recent academic study (“Cutting with both arms of the scissors: the economic and political case for restrictive supply-side climate policies” by Fergus Green & Richard Denniss) that looks at the utility of supply-side restriction in the battle to mitigate climate change (emphasis added):

Significantly, many countries rely on complicated and evolving combinations of these measures, wherein restrictive supply-side policies play an important role complementing demand-side policies.

Policies to control tobacco smoking in Australia provide an instructive example. The policy mix includes prohibitions on producing tobacco without a license, selling tobacco without a license, selling tobacco to children, tobacco advertising, tobacco sponsorship, and smoking cigarettes in confined public spaces. It also includes heavy taxation of tobacco consumption, hard-hitting public information campaigns, “plain packaging” laws, mandatory health warnings on cigarette packages, and the subsidisation of certain substitutes for cigarettes such as nicotine patches.

None of these anti-“free market” measures is considered out of bounds by the public in the war on tobacco use:

Far from being derided as an inefficient mire of “red tape”, Australia’s tobacco regulatory environment is lauded as a global model of effective public health policy, with the country seen as an early mover in innovative regulation in the sector (Chapman and Wakefield 2001). The combination of a wide range of policies, rather than an ‘optimal’ policy, is, moreover, endorsed in the World Health Organisation Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, which states that “‘tobacco control’ means a range of supply, demand and harm reduction strategies that aim to improve the health of a population by eliminating or reducing their consumption of tobacco products and their exposure to tobacco smoke…” (article 1(d)).

As the authors also note, supply-side restrictions “have also played an important role in efforts to reduce negative environmental pollution externalities, including chlorofluorocarbons (Haas 1992), asbestos (Kameda et al. 2014), and lead in petroleum products (Needleman 2000).”

4. Restrictions on demand for fossil fuels alone aren’t doing the job, certainly not fast enough. The march to a far less human-friendly climate — what I’ve been calling the Next New Stone Age — is relentless and accelerating. Again, we are now seeing zero degree Celsius days in February in the Arctic. In plain English, that means this: air, warm enough to melt ice, in the Arctic, in winter.

Restrictions on supply are therefore critically needed. Yet restrictions on supply create discomfort, both for producers and consumers. Can counter-arguments that point to “discomfort” as a reason not to address climate change via fossil fuel supply restrictions be overcome?

5. The surprising answer is yes, those arguments can be overcome. The paper cited above notes both economic and political benefits of restricting the supply of fossil fuels, and shows that, controlling for other factors, those arguments can be popular and effective. To my knowledge, it’s the first paper to do so.

It points out that the economic benefits of supply-side restrictions include low administrative and transaction costs, higher certainty of abatement outcomes, positive price and efficiency effects, the avoidance of infrastructure “lock in,” and others.

On the political side, the authors assert that “supply-side policies are generally likely to attract higher public support than demand-side policies, all else equal.”

Scholars have identified various reasons, related to these factors [perceived benefits, distributional fairness, and so on], why people tend to prefer certain kinds of climate policy instrumentsover others (e.g. command and control regulation over market-based instruments) (Jenkins 2014; Karplus 2011; Rabe 2010) and, within a given class of policy instrument, certain design features(e.g. explicit earmarking of revenue from market-based instruments) (Drews and van den Bergh 2015, 863; Rabe and Borick 2012). What has not been analysed is the effect on public support resulting from whether the instrument targets the supply side or the demand side (controlling for instrument type and relevant design features such as, where applicable, revenue allocation).

The point of the study is to support that point by “controlling for instrument type and relevant design features such as, where applicable, revenue allocation”.

For example, on the “perceived benefits” of demand-side vs. supply-side climate policies, the authors state:

A common conclusion from climate-related public opinion research is that climate science is poorly understood and concern about the problem, though widespread, is shallow, i.e. it tends to be a low-salience, low-priority concern and individuals have a low “willingness to pay” for solutions (Ansolabehere and Konisky 2014; Guber 2003; Jenkins 2014, 470–72; van der Linden et al. 2015). This is unsurprising: the climate benefits of mitigation policies are diffused widely across time and space; they disproportionately accrue (and are perceived accrue) to future generations and people in other countries; and their magnitude is uncertain, meaning they are likely to be strongly discounted by voters (van der Linden et al. 2015).

Supply-side policies suffer none of these disadvantages:

By contrast, supply-side instruments typically target fossil fuels per se. Survey evidence suggests that people more readily link co-costs/co-benefits (environmental, health, security, social, economic) to specific energy sources than to the more abstract concepts of “carbon”/“climate” (e.g., Ansolabehere and Konisky 2014); and fossil fuels are well-understood commodities that many people more readily associate with a range of higher-priority, more localised and more immediate negative (non-climate) impacts, resulting in negative attitudes toward fossil fuels, especially coal (see Green 2018, section 3.1.1 and references there cited). These features give supply-side policies considerable advantages in attracting public support for climate policy. Relatively high public support for fossil fuel severance (resource extraction) taxes, even in climate-ambivalent, tax-averse north-American states and provinces (Rabe and Borick 2012, 377–79), provides circumstantial empirical support for these arguments.

The paper studied similar support for supply-side policies based on perceptions of distributional fairness and lower costs.

6. The bottom line is: This is the first study that controls for other factors in determining support for supply-side climate policies vs. demand-side policies by themselves, and finds much to be encouraged about.

The authors conclude:

In our experience, the climate policy community has for too long been excessively narrow in its preference for certain kinds of policy instruments (carbon taxes, cap-and trade), largely ignoring the characteristics of such instruments that affect their political feasibility and feedback effects. At the very least, then, we hope we have shown that supply-side policies should be in the toolkit, ready to be wielded when circumstances favour.

Better, we think, to cut with both arms of the scissors.

Cutting with “both arms of the scissors” means using both supply-side policies and demand-side policies in addressing the looming climate crisis. It’s clearly ineffective to use just one.

Only the Climate Policy Community Can Lead in Making This Change

Note the addressee of the authors’ conclusion — the “climate policy community.” This recommendation is not addressed primarily to politicians, who in the West are natively “free market” apologists, which means, natively Big Money enablers.

And it’s not addressed to the public at large, who fear — and are led to fear — the “discomfort” of supply restrictions. Recent American Petroleum Institute ads, for example, say this in effect to consumers: “Do you like that big-screen, smart-phone lifestyle of yours? Be sure to keep carbon in the energy mix, or you’ll lose it.” Yet the reality is, if Mr. and Ms. Consumer truly hope to keep their smart-phone lifestyle intact, they better start now to arrest the devolution to Stone Age life that constantly burning carbon will cause — just the opposite of what the API is telling them to do.

It makes sense then, does it not, that a message that clearly explain the benefits of reduction — and destruction — of fossil fuel supply can only be carried at first by leading climate activists and the broader policy community?

I see no one else to offer it. And considering both the existential nature of the coming emergency and its near-suffocational timeline, that leadership needs to start … well, now.

A common proxy for the credibility of a proposal is the strength of belief of the proposer. A radical expert position is naturally doubted by non-experts when the expert proposes on the face insufficient solutions and they tend to suspect demagoguery in service of a hidden agenda.

If an apocalypse is approaching, the naive observer would expect radical responses. It’s a version of the Overton window. If progressives want conservatives to take them seriously, they have to propose serious solution and not Obama style weak sauce compromises that disappear into the social noise.

like:

all buses subsidized with federal dollars will be hybridized or replaced with such by 2020

all transportation program vehicles funded with federal dollars will be electrified or replaced by 2021

all government buildings will be fitted with energy gathering devices next week or asap

all electric vehicles must include a solar array starting now

requiring climate curriculum be included in every science course k-12

enacting a US moratorium on any pipeline construction for 6 months until a US Energy Outline can be agreed upon

requiring all major oil companies to outline how they are going to transition out of oil in order to not be nationalized and their holdings liquidated to compensate pension fund investors in lease money spent

banning plastic bags by 2019–

requiring point of purchase recycling to maintain a business license

require Peter Pan to take back his used pretty washed clean jars instead of leaving it all to me

more, and details, to follow

350.org advocates the same approach as this article–the operational imperative is right now

by each one of us

If Climate Repair activists want to be taken seriously by the public they hope to persuade, those Climate Repair activists will have to adopt voluntarily in open view the low-carbon lifestyle for themselves which would be extended to everybody under the concept of supply restriction.

If the Climate Repair activists all adopt an openly visible low carbon lifestyle in line with what they hope to produce for everyone, they will be respected and given a respectful hearing. If they continue living an abundant-carbon lifestyle their own selves even as they preach supply restriction for society in general, they will be dismissed as virtue-signalling moral-superiority stuff-strutters; thereby guaranteeing the rejection of what they are recommending.

So the Climate Repair activists have a personal life-style choice to make, and to be seen to be making.

Huge inequality + increasing poverty + not yet enough adoption of alternatives + not enough supply of alternatives + lack of will for government spending on adjustment or infrastructure + political polarisation + USA’s desperate dependence on fossil fuels for EVERYTHING = bad idea to implement a supply side restriction right now. If it can be done so that the burden is most on those who can afford it the most, then maybe.

If we had a job guarantee or BIG or something similar, or if we had a great public transportation system that was not fossil fuel dependent to get people to work, then you might be able to restrict supply without starting a Mad Max society.

Instead of advocating for beneficial policies like those, the powers that be are busy trying to put more traffic on the roads in the form of driverless cars. Having them run down the newly unemployed will take the place of the job guarantee.

I’d like to see something along the lines of a CCC for young people. Call it the Climate Corps or the Earth Force. Have ’em go through a boot camp like the military — to build an espirit de corps and to strengthen their bodies — and then turn them loose on big problems like climate change.

For us middle-aged and older folks, how ’bout something like a volunteer corps for weekends or service vacations? I know I’d be itchin’ to sign up!

They will remove (non-wealthy) humans from the road.

I see cars being priced out of reach for human drivers by insurance and the manufacturers.

They envision a future where there is ride “sharing” with an autonomous vehicle or what may be left of public transportaion. (unless you can afford otherwise)

Bans on oil and gas exploration are surprisingly popular with the public. France has passed a ban without much fuss, Ireland has banned fracking and may shortly ban all oil and gas exploration. The Irish example is perhaps more noteworthy as unlike France it has substantial onshore frackable gas reserves and conventional off-shore oil/gas deposits.

If there is a positive from the fracking boom in the US it has put major pressure worldwide on the fossil fuel majors in terms of public awareness of the impacts of production and the downward pressure on oil/gas prices has devastated the off-shore exploration industry.

iirc, after Al Gore’s Inconvenient Truth tour it came out he’d invested in a mechanism for profiting off of carbon tax credits. Nice gig… It didn’t get any play until it was a commodity to be traded.

The following is approximately right rather than exactly wrong: Europeans can afford the luxury of holding onto their supply for a later date because they have ready reserves from Russia and military protection from the U.S. Shortages in either of those would force them into a more competitive eco system and they’d have to cash out.

so? i dont know if this is true or not, but the science is clear that we need to get off fossil fuels as soon as possible. al gore didn’t invent the science. the price of a gallon of gas or a quantity of coal should reflect the future damage. the artificially low prices are very dangerous.

in other words, let’s create a insanely massive layer of bureaucracy with power over every single resident of this planet.

that will surely work to solve our carbon woes. see how well it worked with obamacare?

if you want people off of fossil fuels you have to provide an actual, functional alternative.

@Kimyo: tax ff production to death. Already IRS is an insanely massive layer of bureaucracy, right? Actual, functional alternatives will come out of hiding in university labs if there’s demand, I.e., money in it.

@lymanab: lots of problems with Gore, but the hockey stick image is a hugely powerful message about runaway increases in heat.

“if you want people off of fossil fuels, you have to provide an actual, functional alternative.”

That’s a cold, hard truth that Gaius Publius’ commentary fails to acknowledge. Comparing fossil fuels to tobacco is a deeply flawed analogy. After all, even if we cut tobacco production to ZERO, our lives and economy would continue to hum along, largely unchanged. [Well, there would be some ex-smokers who would be deeply annoyed, but they too would eventually cope.]

If we were to similarly cut petroleum, coal, and natural gas production to ZERO, over 99% of the vehicles on the road would stop running. And people living in colder climates, no longer able to reliably heat their homes, would starting freezing to death on cold winter nights. The economic damage and human suffering would be enormous. For examples of how supply-side restrictions actually play out in the real world, see these two examples from China. Note that both efforts were discontinued because they were too disruptive.

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-42266768

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/sep/19/china-blackouts-energy-efficiency

Even partial restrictions could result in 1970s-style gas rationing and sharp increases in energy prices. And America’s poor would bear the brunt of the pain. Without actual, functional alternatives, this will go nowhere.

yeah you have to provide a functional alternative and cut fossil fuels simulataneously, you don’t wait till you have a full alternate system in place. we need sharp increases in energy prices, and a rebate based on income.

I’m wondering what Rupert Sheldrake would suggest. All it takes to change our ways is a fraction of us doing something different, and doing it successfully. Critical mass. Having some guaranteed “alternative” is a ticket for procrastination. Humans have evolved to adapt. If that’s not a redundant sentence… Just look at China when they killed off all the bees with pesticides and the government told the fruit growers to polinate their trees manually. They collected the polin and applied it with little feather dusters. And kept producing apples. I’m thinking how nice snow-days are. They let us sit back and take a deep breath. We can grab the shovel and dig ourselves out – and when we’re done it feels so good. That whole idea of snow-days is like immediate positive feedback for not doing things the usual way. Learning to be both efficient and self-sufficient is a welcome lesson. Recapturing lost lifestyles. It would help to award innovative ideas for alternatives to fossil fuel. The government can subsidize lifestyle changes. Just like they dismantled the railroads and promoted cars, they can phase out cars and promote other transportation. And etc.

As an old geezer who has to shovel the driveway and other areas, I’m starting to wish there weren’t quite so many wonderful opportunities to improve my health. They’re killing me. But I get your drift…

Thank you Susan, I wish more would wonder what Rupert Sheldrake would suggest.

From searching the archives I see he is no stranger to NC.

May I suggest a 1993 Dutch documentary I recently watched on YT:

A Glorious Accident (1 of 7) Oliver Sacks on migraine [ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BVkobRTbG8A ]

(2 of 7) Rupert Sheldrake: Revolution or wrong track?

(3 of 7) Daniel C. Dennett: The last resort of humanity

(4 of 7) Stephen Toulmin: Descartes, Descartes

(5 of 7) Freeman Dyson: In praise of diversity

(6 of 7) Stephen Jay Gould: The Unanswerable

(7 of 7) Coming together: We wonder, ever wonder why we found us here

Calm discussions, what a novelty! What a line up!

I thought what Hans Werner Sinn had to say about this in a recent lecture at the LSE Grantham Institute was interesting, see video

Hope this link works.

Not sure it is any more politically feasible than carbon reduction targets, but they sure are not working either.

Very interesting in the NC commentariat’s thoughts.

There’s a big difference between the public agreeing to a policy in a survey and actually seeing those results in the real world. In surveys, Americans agree to much more redistributive economic policies than the ones that actually exist in the US. But most lack awareness of public policy, making it easier for big business to dominate. And often when presented with two candidates, one very conservative on economic policy and the other extremely conservative, the public might support the latter one for whatever reason (maybe he is more charismatic, gets more donations, receives better media coverage, etc.). A lot of people aren’t even aware that there are alternatives such as the ones mentioned in this paper because our representatives never discuss them.

Nationalize the fossil fuel industry. Allocate $16 trillion to the development of alternatives. It’s the economy that must get off of carbon, just as individuals must get off of cigarettes. As Ape said in the first comment, a radical problem requires a radical solution.

I proposed that to James Hansen at a talk on one of his books and he scoffed.

If the arctic and antarctic are melting at 400 ppm carbon and 1 degree C,

have we reached a tipping point ? And, were humans to reach zero carbon, how do you get the melting tundra to do the same?

I see this as equating a bookkeeping entry ($16Trillion) to real resources (such as CO2-free energy production, plentiful food, or scarce metals).

I fear that Mother Nature is not behaving as a teacher who has given a problem (climate change) to humans that CAN be solved.

If one assumes human population continues to grow and people continue to demand a better lifestyle (as in more consumer goods, more meat, more interior comfort, less physical labor), the problem gets ever more difficult.

Perhaps if we were to view the environment from the eyes of other lifeforms, we can foretell the future.

For example, during a recent tour of a Northern California marine research center, the tour guide mentioned that 90% of the kelp beds have disappeared off the California Coast.

See https://www.kqed.org/science/1357320

See the status of the fisheries at http://www.oceanhealthindex.org/methodology/components/fisheries-status

The World Bank has that about 80% of the world’s energy comes from fossil fuels and has been around this percentage +/-2% since 1980 (37 years).

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.USE.COMM.FO.ZS?view=chart

I’m skeptical there is some technological miracle (cold fusion?, very inexpensive PV cells?, CO2 capture?) waiting in the wings that can scale up to make a long term difference.