Yves here. Some sightings: Trump is signaling that he might exempt Canada and Mexico from his tariffs. The EU has already developed a list of US products against which it would levy retaliatory tariffs, and the value reported is very close to the one Bown says is allowable, confirming his analysis.

By Chad Bown, Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics; CEPR Research Fellow. Originally published at VoxEU

President Trump’s announced intention to impose import tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium touched off a wave of retaliation threats and trade policy responses from trading partners, including the EU. This column examines the scope for retaliation against the Trump administration’s proposed tariffs under WTO dispute settlement. It estimates that if the sources of all US steel and aluminium imports were part of this dispute, trading partners would be permitted to retaliate by a collective amount of $14.2 billion per year.

President Trump’s announced intention to impose import tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium touched off a wave of retaliation threats and trade policy responses from trading partners, including the EU. Countries are reportedly already lining up their product lists of US exports over which to impose tariffs of their own. But what are we to make of these threats?

President Trump had kept under wraps the steel and aluminium products being investigated under Section 232 of the 1962 trade law that he is relying on to curb imports. Only after the investigation’s reports were finally made public on 16 February did it become clear that the tariffs – which his administration claims are necessary to protect national security – will cover $46 billion dollars of imports (US Department of Commerce 2018a,b). However, only 6% of those imports derive from the country the administration has labelled as the main culprit in flooding the world with steel and aluminium – China (Bown 2018).

Rules established by WTO dispute settlement permit a country to retaliate against an action such as the one Trump plans to take if there is a legal finding that the national security rationale is baseless. The compensation – or retaliation – limit has historically been set at the value of an exporting country’s lost trade.

However, it could take years for retaliation under the process of formal WTO dispute settlement to unfold. As a result, countries may take other steps to circumvent that process, while at the same time claiming that they are relying on basic WTO rules to guide their retaliation response.

Using information reported from the Trump administration’s own models, I estimate that Trump’s steel and aluminium tariffs would impose trade losses on partners equal to $14.2 billion per year, an amount establishing the collective permissible retaliation. The countries hit the hardest by Trump’s tariffs are Canada ($3.2 billion), the EU ($2.6 billion), South Korea ($1.1 billion), and Mexico ($1.0 billion).

Importantly, China would only suffer $689 million in estimated trade losses and thus only be authorised that much in retaliation. The US currently imports relatively less steel and aluminium from China because previously imposed antidumping and countervailing duties have already severely limited US imports from China of those products (Bown 2017a).

The WTO Dispute Settlement Approach

Here is how the WTO would approach the issue. Given the completed investigations under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, assume that Trump proceeds with tariffs of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium. WTO member countries would then challenge his claim that the tariffs are justifiable under the GATT Article XXI “national security” exception. Further assume a WTO Panel and the Appellate Body reject Trump’s defence and find the tariffs inconsistent with US obligations.1 In that event, suppose the Trump administration nevertheless refuses to amend the tariffs. Complaining countries can then request compensation and the WTO can establish authorised retaliation.2 Cases like these are rare – the WTO has established the retaliation limit in fewer than 15 disputes since 1995, and in even fewer instances have countries implemented the retaliation.

WTO retaliation is not punitive. Under the principle of reciprocity, the WTO would limit the amount “equivalent to the level of nullification and impairment” that resulted from Trump’s policies. In practice, establishing the limit requires that WTO arbitrators follow a two-step process: (1) decide on a mathematical formula, and (2) decide on key parameter values so as to apply that formula to the context at hand.

In disputes involving WTO-inconsistent import restrictions – e.g. tariffs, quotas, and non-tariff measures that limit imports – arbitrators have settled on use of the ‘trade effects’ formula. Historically, the formula has been defined as the difference between imports under the WTO-inconsistent policy and a ‘counterfactual’ level of imports that would have arisen but for the policy. That is the formula applied here.

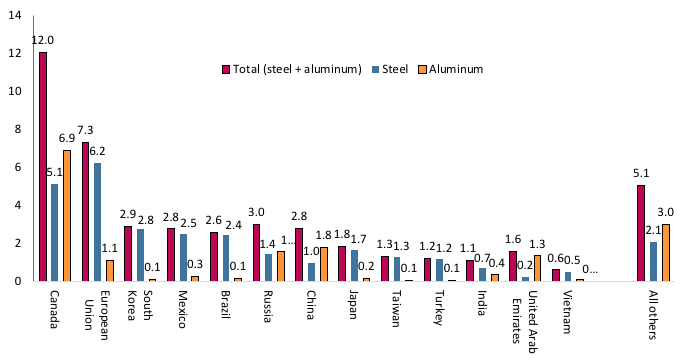

The second step involves deciding on the monetary values to be assessed. First, for the counterfactual values for trade flows in the absence of Trump’s tariffs, I use the 2017 levels of US imports of the investigated products and subject to the tariffs. Overall, these were $29 billion for steel and $17 billion for aluminium.3 Figure 1 illustrates the foreign source of 2017 US imports by product and by partner. Top foreign sources for both products combined include Canada ($12 billion), the EU ($7.3 billion), Russia ($3 billion), South Korea ($2.9 billion), and Mexico ($2.8 billion).

Notably, China exported only $976 million of steel and $1.8 billion of aluminium products to the US, or just 6% of the $46 billion of US steel and aluminium imports over which Trump is imposing tariffs.

Figure 1 US imports of steel and aluminium in 2017, be selected trading partner (billions of US dollars)

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on matching the Harmonized Tariff Schedule product codes in the two Section 232 reports (US Department of Commerce 2018a, b) to 2017 import values from the United States International Trade Commission Dataweb (aluminium) and Commerce Department’s Import Monitor (steel).

Second, I rely on the Commerce Department’s own estimates from the Section 232 reports (US Department of Commerce 2018a,b) to establish estimates of the levels of trade that would result from Trump’s tariffs. For steel, the report alludes to an economic model that claims a 24% tariff is equivalent to an import volume reduction of 37%. For aluminium, the claim is that a 7.7% tariff is equivalent to an import volume reduction of 13.3%. As I do not have access to their underlying models, I assume a linear relationship between each product’s tariff and its trade volume reduction. Under this assumption, Trump’s proposed 25% tariff on steel would lead to a 38.5% cut in steel imports, and a 10% tariff on aluminium would lead to a 17.3% cut in aluminium imports.4 I apply these cuts to bilateral US imports of steel and aluminium in 2017.

Who Would be Authorised to Retaliate and by How Much?

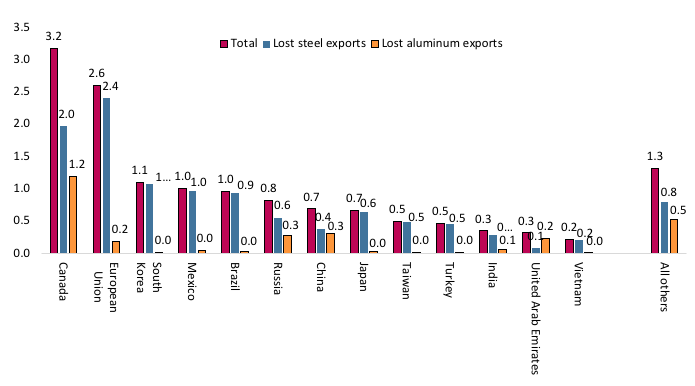

Figure 2 illustrates the total amount of each country’s retaliation, as well as whether the lost trade derives from lost steel or aluminium exports. Because Trump’s proposed tariffs would be applied to imports from all partners equally, trade losses will be largest for countries that are the largest sources of US imports of steel and aluminium.

Canada would be granted the largest retaliation at $3.2 billion (for $2 billion of lost steel exports and $1.2 billion of lost aluminium exports). The EU would be granted $2.6 billion ($2.4 billion for steel, $0.2 billion for aluminium), followed by South Korea ($1.1 billion), Mexico ($1 billion), Brazil ($965 million) and Russia ($823 million). Others with sizable losses include Japan, Taiwan, Turkey, India, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam.

Figure 2 Estimated lost exports and retaliation limits if Trump imposes tariffs (billions of US dollars)

Note: Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

Source: Author’s calculations as explained in the text under the assumption that President Trump imposes an import tariff of 25% on steel and 10% on aluminium.

China would only be authorised to retaliate by $689 million ($376 million for lost steel exports and $313 for lost aluminium exports).

If the sources of all US steel and aluminium imports were part of this dispute, trading partners would be permitted to retaliate by a collective amount of $14.2 billion per year. The largest authorised WTO retaliation to date is the $4 billion that the EU was authorized to retaliate at the conclusion of the United States—Foreign Sales Corporation dispute in 2002. The second largest was the US—Country of Origin Labeling dispute in which Canada was authorised to retaliate by $1.1 billion in 2015.

How Might Countries Implement the Retaliation?

Countries frequently implement WTO retaliation by imposing 100% tariffs on a list of imported goods from the defendant that add up to less than the authorised limit. The logic is that the 100% tariff may be prohibitive; this would thus eliminate no more than that WTO-authorised limit.

The next decision for the retaliating country is to identify which products to put on its list. In the case against Trump, the EU has reportedly indicated its product list will include jeans, bourbon from Kentucky, cranberries and dairy products from Wisconsin, Harley-Davidson motorcycles, US steel products, and agricultural products like rice, maize, and orange juice (Donnan and Wigglesworth 2018).

The complaining country typically has discretion to determine which products to target. It may select products based on political motives – for example, inflicting economic costs on key Congressional leaders in the hope that they will effectively persuade Trump to implement policies that conform with international rules.

Finally, it is also worth noting that authorisation of retaliation arising from a WTO dispute can take many years to play out.6 For that reason, trading partners may also impose more immediate import restrictions – perhaps also guided by these ‘compensation’ (retaliation) limits set out here. They may argue that Trump’s original tariffs should be viewed not as a justified national security exception but as a safeguard, in which case partners can request a more immediate remedy, for example, if there was not an absolute surge in the imports being protected.7

Author’s note: I thank Junie Joseph for outstanding research assistance and Olivier Blanchard, Monica de Bolle, Mary Lovely, Jacob Kirkegaard, Ted Truman, and Steve Weisman for helpful discussions and comments.

Endnotes

1. For a discussion of GATT Article XXI see Yoo and Ahn (2016). In this column I will not comment on the legal question of the WTO-consistency of Trump imposing tariffs under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. I assume they are WTO-inconsistent for the purpose of establishing one aspect of the potential costs – in the form of authorisable trading partner retaliation against US exports – of such tariffs.

2. This is discussed more formally in Bown and Ruta (2010) for disputes prior to 2008, in Bown and Brewster (2017) for the US – Country of Origin Labeling dispute involving Canada and Mexico, and in Bown (2017b) in light of a potential dispute involving the proposed border adjustment tax.

3. Computed as described in the note under Figure 1. These data were not included in the Section 232 reports but had to be constructed independently based on information provided therein.

4. This implicitly assumes that the exporter-received price for steel and aluminum will not fall because of the tariffs, a dubious assumption given the size of the United States as an importer and its likely market power. As discussed in Bown and Brewster (2017, 382) what results is retaliation limits that should be treated as the lower bound. If exporter-received prices fall considerably because of the tariffs, authorized retaliation could be even larger.

5. Horn, Johannesson, and Mavroidis (2011, table 22) show the average length of time that disputes taking place spent at each phase of the WTO’s full dispute resolution process between 1995 and 2010.

7. This may be what is motivating the EU’s potential response reported in Shawn Donnan and Wigglesworth (2018).

See original post for references

This is so bizarre.

I don’t see how you can say, in a world continually at war – and I wish as much as anybody that it wasn’t, how f’ing stupid – that internal steel and alumninum capacity aren’t necessary for national security.

And the numbers are comically small in relation to even Canada’s pathetic GDP (sorry mates, just joshing you a bit), let alone when you add up all the countries affected. 14.2 billion? For everybody? Couch change.

What a nothingburger. Beyond being, that is, a chance for Serious People, especially mainstream economicists, to flounce around and act butthurt because democracy.

So, if I understand you correctly, Trump and the US are entitled to ignore treaties and international obligations because the amounts involved are peanuts? As an analogy, if I steal only, say, $500 from you would you ignore it because it is peanuts?

As for democracy, which you seem to invoke as some magical incantation to justify any arbitrary act by a sovereign, how is a unilateral refutation of international agreements the act of a democratic leader? Given Trump’s level of support and the general negative view of his stance on tariffs, this seems like anything but democracy.

As for national security, the US has managed to wage countless wars and invade a record number of countries, slaughter hundreds of thousands of foreigners (mainly Arabs) and transfer trillions of dollars to the Military-Industrial complex over the past fifty years without having adequate domestic production of steel and aluminium. Why now? Other than Trump’s twisted view of what makes a country great (hint: whatever he thinks makes HIM look great).

Boy you know how to reach a guy. Did you read a single word I said?

First paragraph: where did the word “entitled” or “ignore(d)” show up in my response?

Second paragraph: “how is a unilateral refutation of international agreements the act of a democratic leader?” Don’t know where you pulled that out of my post, but I’ll answer: Because a “democratic leader” is elected to represent the will of his people, right or wrong.

Third paragraph: Yeah, I know we suck. That doesn’t obviate the more generic question. Can you tell somebody that they can’t do things to protect themself? Try murdering a guy on death row and see how the law regards you.

Anti-Trump rants have gotten us nowhere, but I hope yours made you feel better. How about the Democrats didn’t make a world where Obama was (and Clinton expected to be) basically the dictator that you seem to have confused with “democratic leader”. Maybe Trump couldn’t pull the (family blog) that he does?

You are right $14 billion is chump change. Trump with his delusions of grandeur thinks he is doing something big, no biggly.

But with the list of retaliation targets Wisconsin will bear the brunt of it. Cranberries, dairy and motorcycles.

Cranberries? The only time they hire is in fall for harvest. Dairy? Wisconsin CAFO’s are notorious for their illegal employees and manure wages, that and polluting the states groundwater. Harley? Even Harley has turned into a shit job because the union threw the younger new hires under the bus with a separate wage scale for temps which all the new employees are. For a new hire working for Harley isn’t any better than WalMart or burger flipping. So, really the only adverse impact will be on capital.

The whole thing is a Trump nothing burger except for Wisconsin’s capitalists.

“that internal steel and alumninum capacity aren’t necessary for national security”

Well they aren’t, the very basis of your argument is broken. 2/3 of steel used in the U.S. is already manufactured here and with the largest military on the planet by a stunning margin along with the realization that there will never be a land, sea and air campaign requiring masses of steel again, that 2/3rds is more than enough to keep us perfectly safe.

Now, the resulting impacts of stupid tariffs on international trade agreements and the downstream effects on the U.S. and world economy will be anything but peanuts.

New frontiers in unilateralism:

America’s last constitutionally-declared war began in 1941. Now “wartime” has degenerated into a solipsistic state of mind that we can declare as casually as a bad hair day.

What’s clear is that the US, which designed itself as the mighty sun at the center of the post-WW II monetary and trade solar system, has slunk ignominiously out the back door. Now it’s a penny-ante carper and caviler, scheming to swipe nickels from the other players … which is no way compatible with its self-appointed privilege of issuing the global reserve currency. :-0

I don’t think it is correct to say that the incidence doesn’t fall on China because the US isn’t buying directly from China.

Steel is largely fungible and China produces literally half the planet’s steel. Any slackening in international demand for steel will be felt indirectly by China, because reduced US purchases of Canadian steel and EU steel will reduce the international price of steel overall.

This is also precisely the reason that bilateral trade penalties against China for steel dumping will be and have been ineffective.

Better to have sat down and negotiated with the allies that produce the types of steel that China produces to set a joint set of focused tariffs. But that would require a) thinking; b) allies; and c) negotiating, none of which are Trump’s fortes.

I still think this is about the SW Penn house district and Trump very well could just drop the whole tariff thing and move onto something else after that special election. that would fit his normal time frame for attention span.

Yes, if you want to build your steel industry, then build your steel industry. Don’t use it to play favorites. The best trade policy is like the stuff that brought the (quite arguably better) Japanese auto manufacturers to our soil. Doesn’t mean even that path can’t go bad, like the Wisconsion Foxconn screw over. In fact, it will. Everything degrades.

It’s hard work to get this right, it needs to be attended to every day, it need a solid set of principles, and it needs said set of principles to be continually under review. “Getting it right” is always temporary, too. But can’t grandstand on TV with that, can we?

Everybody wants an eternal set of precepts. Too bad, world doesn’t and won’t ever work that way.

Interesting analysis. For what it’s worth, though I haven’t read Yoo and Ahn yet, I think the US legal case is pretty strong. The national security exception was intended to let the member countries have broad latitude to define their own national security interests in a war or emergency, and courts don’t usually like to second-guess decisions about national security. If the government of China thinks that suppressing dissent is essential to its security and bans imports of books, WTO officials just aren’t going to be happy saying no. Also, whatever may be said about the rest of the Trump administration, its trade officials know what they’re doing. Lighthizer has spent his entire career working on tariff law, and so have many of the lower officials.

Also, I think the EU case for considering this a safeguard measure is weak, and its case for immediate retaliation weaker still (assuming Trump officials are smart enough to make sure they impose tariffs on products that have been increasing in import volume).

All that said, the WTO has a strong bias toward free trade, regardless of the language of the agreements. If the US can impose tariffs in this case, other countries will surely follow its lead, and WTO rulings will lose relevance. So it’s probable the US will ultimately lose in the WTO appeal process. So will the EU if it imposes immediate tariffs.

At that point, what usually happens is both sides declare victory and withdraw their tariffs. Trade officials give a sigh of relief, US steel manufacturers pocket a couple of years’ extra profits, and unions maybe get a few crumbs, or at least a couple years’ reprieve from layoffs. But with Trump, anything can happen.

The US could just declare that for industrial products it is a “developing country”. The South Koreans have done this for agriculture, allowing them to have ultra high tariffs on agricultural imports. The US is the side with an $800 billion trade deficit – that’s $8 trillion over a decade in lost aggregate demand. The rest of the world could absorb an $800 billion trade surplus from the US much easier than the US can, and if the US had a trade surplus of 3% you would be paving the streets with marble and gold. Economics is not rocket science! Follow the East Asian Model, it’s not difficult!

the trade deficit is a function of the dollar’s global reserve currency status. the US would not have an empire without it. you cannot have the global reserve currency and a trade surplus at the same time.

that said, it certainly is true that most people (in the US and the world) would be better off if the US gave up its empire and started having trade surpluses. the average briton was probably the biggest beneficiary of the fall of the british empire.

I keep waiting in vain for someone to bring up the word “ore” (i.e., iron and/or aluminum). e.g., the US is the 8th ranked iron ore miner, producing 1/20th the annual amount of #1 Australia (moreover, across the past century, the relative “usability quality” of US ore has declined dramatically). Is Trump proposing that we’re gonna put these US miners “back to work” also, in addition to the mill hands? 100% “US steel” implies that it was made from US ore.

And, if we don’t also slap tariffs on foreign steel/alum-containing finished products, doesn’t that spur more foreign manufacturing incentive? So much for “creating and protecting US jobs.”

Maybe Secretary Zinke can sell off the entire National Park system so we can strip-mine them for remaining domestic ores (which can then be shipped overseas, ‘eh).

The amount of money is small as noted here. However, they have been strategically targeted. One counter-tariff is for Harley-Davidson motorcycles which I found odd until I found out that they were located in the heart of the seat of a major political figure and so were the others. This makes for a lot of sad faces in Washington.

The tariffs were supposed to be all about China but they are about number 11 on the list of steel-importers with only about 2-3% total. The other countries are nearly all allies such as Canada (16%), Brazil (13%), South Korea (10%), Mexico (9%), etc. and will not be happy. Apart from any official counter-tariffs, they might decide on asymmetrical pressure point on the US regime.

Canada might announce that it cannot now afford all those F-35s they were going to buy. Mexico might call back every single Mexican in the US and let the yanquis do all their menial work. Brazil might say that that US oil exploration outfit has now missed out on the running for that new oil field. South Korea might say that they have no longer have time to take part in the next exercises practicing the invasion of North Korea.

Add it all up. A billion here, a billion there – pretty soon you are talking about serious money here.

The article notes “However, only 6% of those imports derive from the country the administration has labelled as the main culprit in flooding the world with steel and aluminium – China”, without further comment on what appears to be a curious and explanation-demanding disparity.

As reader JCC reminds us over in the nextdoor reprint of Marshall Auerback’s Alternet piece, back in 2016 St. Obama imposed a massive 266% duty on imports of Chinese cold-rolled steel, with a much more muted response from the globalization shills populating the MSFM. Might said tariffs have to do with the relatively tiny impact of the new ones proposed by Trump? (I couldn’t find a reference as to whether they are still in force.)

i still don’t get something. trump can unilaterally impose tariffs without fear of breaching WTO rules but the EU and others have to follow WTO rules? why can’t the EU just as unilaterally impose a tariff of 20% on all US tech products and cars, even though this would vastly exceed their WTO-approved 2.9b?

(ignoring the fact that the US would re-retaliate and raise more tariffs on EU wine and fashion)

anyway, f*** the US. it’s a rogue state and the world would do well to embargo it. indeed, to have any teeth, the climate accord should impose mandatory tariffs on any country that doesn’t sign on.

It’s not “without fear of”, as was detailed in this other NC piece yesterday:

Trump's Steel and Aluminum Tariffs: How WTO Retaliation Typically Works

The crux of the issue is whether, based on precedents, there is a reasonable expectation of getting a waiver under the national-security ‘out’. (And Trump, being a consummate American-exceptionalist blowhard, may not care about that, either.)

sure, but what i don’t understand is if the EU ultimately feels that the US would re-retaliate if they exceeded WTO limits, what’s to stop Trump from re-retaliating anyway even if the EU stick to WTO limits? i mean, that’s Trump’s entire negotiating schtick. he can threaten any country or block of countries with more tariffs if they so much as think about retaliating. who’s to stop him?

Ok, I’ll admit to being completely ignorant when it comes to economics and trade policy. But couldn’t these “trade wars” be a good thing? One of the things I read in This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein was how attempts at clean energy and ending fossil fuels was frequently undermined by trade deals. Trump’s careless swinging of a sledgehammer at the billionaire’s precious neoliberal economic model, while intended to create a libertarians wet dream, could actually create an opportunity to finally bring down neoliberalism once and for all. Progressives just need to push…and push hard…to replace it with a progressive system once the neoliberal system comes toppling down.

That’s how I see it at least. I’m just an engineer though so maybe those of you who understand economics and trade can prove me wrong?