By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She now spends much of her time in Asia and is currently working on a book about textile artisans.

Yesterday, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) announced that it had awarded $83 million to three whistleblowers– the highest payout to date under provisions authorized under the 2010 Dodd-Frank legislation. The SEC is required by statute to protect the confidentiality of whistleblowers and thus not to release information that may directly or indirectly out a whistleblower, and the SEC press release didn’t identify the company concerned.

Both the Financial Times and the Wall Street Journal reported that the information provided by these whistleblowers had helped the SEC achieve a $415 million settlement with Bank of America– citing as their source the lawyer for the whistleblowers. According to the Journal (which, for those interested in further details about what Bank of America did, provides a far fuller account):

That 2016 settlement was the SEC’s second-biggest against a Wall Street bank. As part of the agreement, Bank of America resolved accusations that it misused customer cash and securities to generate profits, putting billions of dollars of customer assets at risk over a roughly six-year period.

How Significant is the Award?

The amount of the whistleblower award might lead the unwary to conclude that the Dodd-Frank whistleblower provisions are a resounding success. Since issuing its first award in 2012 under these new provisions, the SEC has awarded more than $262 million to 53 whistleblowers. What struck me was how few of these awards have been made in the six years since the first award was made, and how little the total amount disbursed has been, given that whistleblower awards under the program can range from 10 percent to 30 percent of the money recovered from a company when monetary sanctions exceed $1 million.

I have written elsewhere about failings of this program (see here and here). So I won’t repeat that analysis here, except to point out that a unanimous 9-0 February Supreme Court decision narrowed the scope of anti-retaliatory whistleblower provisions under Dodd-Frank, requiring that potential whistleblowers must report to the SEC in order to be protected from retaliation and cannot rely on making an internal complaint alone to trigger anti-retaliatory protection. As I wrote in Supreme Court Narrows Dodd-Frank SEC Whistleblower Protections, this makes it more likely that potential whistleblowers will head straight to the SEC rather than first exhausting their internal complaints procedures– rather than relying on the tender mercies of company management not to shoot the messenger.

Now, I should mention here that both the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (2002) and Dodd-Frank (2010) have whistleblower provisions.The scope of anti-retaliatory protection is broader under Sarbanes-Oxley, but most whistleblowers would probably prefer to use the Dodd-Frank provisions, as by going that route, that can receive a bigger payout if the SEC both decides to pursue the matter that the whistleblower brought to their attention and recovers on the claim.

An article in today’s National Law Journal summarized some other concerns:

One of the considerations for a corporate whistleblower is whether to report internally or instead to a regulator and potentially qualify for a whistleblower award. Under some whistleblower reward programs, a whistleblower can report anonymously. But under the False Claims Act’s qui tam provision, a whistleblower’s identity will likely be revealed once the case is no longer under seal. And the type of work that a whistleblower performs at a company can affect the timing of external whistleblowing. While most corporate whistleblowers can disclose fraud to the SEC through the SEC whistleblower program immediately upon discovering the fraud, employees whose principal duties involve compliance or internal-audit responsibilities must report internally and wait 120 days before reporting to the SEC to qualify for a SEC whistleblower award.

How Worried Are Company Employees About the Possibility of Retaliation?

On Monday, the Ethics and Compliance Initiative (ECI) released a report, The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace that addressed this issue. In 2017, 47% of the more than 5,000 randomly selected US employees surveyed said they had personally witnessed conduct that violated either organisational standards or the law– down from 51% in 2013. That finding– that personally observed misconduct has apparently decreased– seems to represent a modest success.

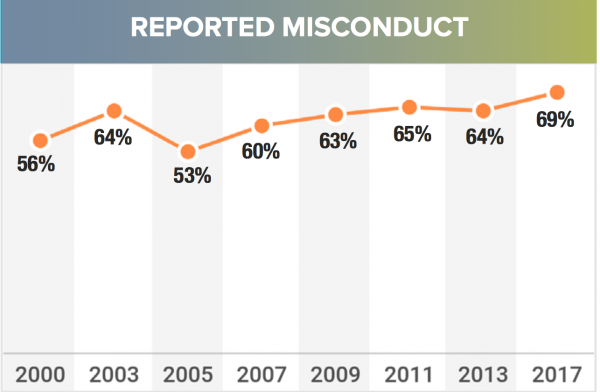

Figure 1.

Source: Ethics & Compliance Initiative, The State of Ethics &Compliance in the Workplace, p 6.

Sixty-nine percent of employees surveyed said they reported the misconduct they observed, up from 64% in 2013. This increase, also appears to represent a positive development. The leading types of misconduct reported in 2017 were: misuse of confidential information (79% of those surveyed); giving accepting bribes or kickbacks (76%); stealing (74%); failed specifications (73%); and sexual harassment (70%).

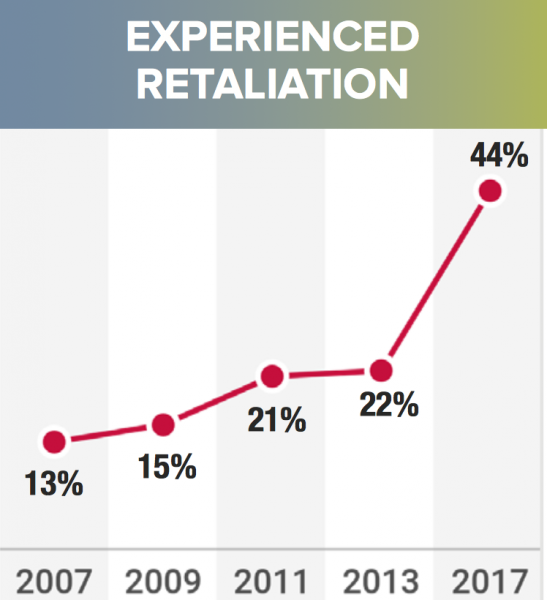

Figure 2.

Source: Ethics & Compliance Initiative, The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace, p 7.

Retaliation Skyrockets

The most significant– and worrying to my mind– negative result the ECI reported was on retaliation. The rate of retaliation against employees for reporting wrongdoing doubled since 2013, rising from 22% in 2013 to 44% in 2017.

While in past years of this research, ECI revealed that reporting and retaliation rise and fall together, what is most concerning is that in 2017, retaliation rose significantly higher than reporting – a 100% increase as opposed to a 7% increase in reporting (report, p. 9).

The report itself didn’t delve into the disconnect that emerged between the increase in reporting and the leap in retaliation. the Wall Street Journal’s reporting on the ECI study, The Morning Risk Report: Whistleblower Retaliation Rising, examines this issue further:

Normally there is close correlation between the rise in reporting and any increases in retaliation so the greater increase in retribution is unusual, said Pat Harned, chief executive of ECI.

“It’s hard to say exactly why. It could be the kind of misconduct people are reporting is more serious or may involve their own supervisor,” circumstances where retaliation is more likely to occur, said Ms. Harned.

“Anyway you look at it, it’s a troubling thing,” she said. “When workers have high rates of retaliation they are far less likely to report things in the future.”

This rise in reporting and retaliation cuts across all companies but is more pronounced in publicly traded businesses than those privately held, said Ms. Harned. For example, 75% of respondents at publicly traded companies said they reported misconduct, with 55% also experiencing retaliation. Among privately held entities, 66% of respondents reported misconduct; 39% said they suffered retaliation.

Another point suggested by the findings but which the Journal didn’t pursue further is that — assuming that these survey results are indicative of a more complete picture– too many of those retaliating do not seem unduly worried about suffering any consequences. That suggests that there is a lack of concern that retaliation– if brought to the attention of regulators– suggests the claims of misconduct might have merit.

There also seems to be little hesitation about retaliating: perhaps it’s too widely considered to be a low-cost response. For when the corporate hammer strikes, it strikes quickly, with 40% reporting retaliation occurred within one week; 32%, within one to three weeks; 18%, within three weeks to six months; and a mere 9%, at six months or more. That means that nearly three-quarters of retaliation occurred within three weeks of the whistleblower first raising the issue.

Sure looks to me like a classic crapification scenario– particularly where retaliation is concerned, and despite the nominal steps that have been taken– such as the Dodd-Frank SEC provisions– to facilitate whistleblowing. Despite the changes, whistleblower protections remain pitifully inadequate. Otherwise, the incidence of retaliation should have dropped, not doubled.

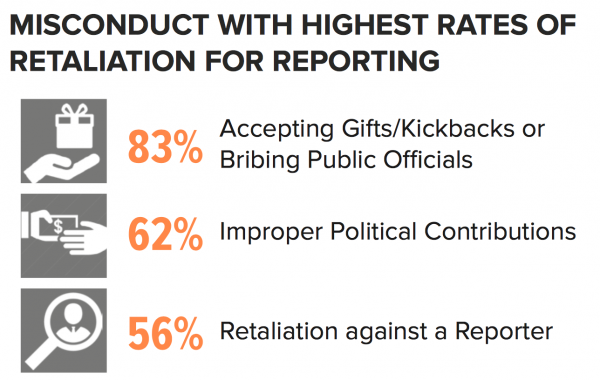

Figure 3.

Source: Ethics & Compliance Initiative, The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace, p 9.

The types of complaints that attracted the highest incidence of retaliation were not trivial either, with 83% being allegations of accepting bribes or kickbacks or bribing public officials, and 62% being instances of political contributions.

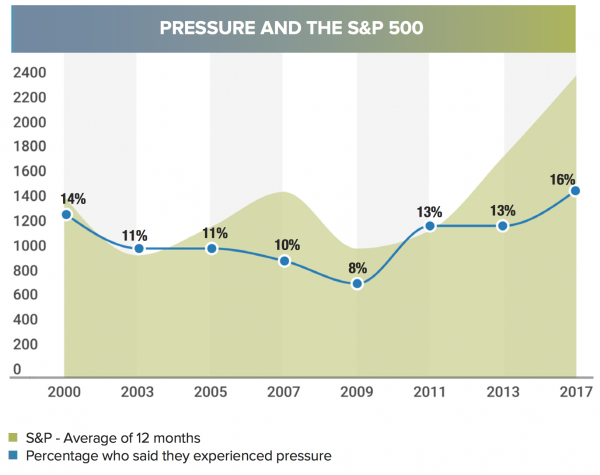

Figure 4.

Source: Ethics & Compliance Initiative, The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace, p 9.

What to Expect Next?

The ECI study closes on a sobering note. First, the report notes:

Historic [ECI Global Business Ethics Survey] studies indicate workplace conduct tends to change with market conditions. This trend continues in 2017. In study periods when the market experienced a downturn, our research showed fewer employees felt pressure to compromise standards. Results of this up- date show that as the market improves, the pressure to compromise increases.

So does that mean that in order for business ethics to improve, we must all pray for a market downturn? Sheesh.

Figure 5.

Source: Ethics & Compliance Initiative, The State of Ethics & Compliance in the Workplace, p 11.

What does the ECI suggest happens next? There, too, prospects are depressing:

These findings are troubling, because increases in pressure have shown to precede a weakening of ethical cultures. As that happens, as already shown in this report, conduct worsens. After nearly a quarter of a century studying employee perspectives of ethics in the workplace, ECI has shown that companies can curb the negative impact of external forces, such as the economy, by taking steps to strengthen their cultures. Yet, this report indicates the state of ethical cultures across the country remain unchanged. Unless organizations take action, it is our view that trouble may be ahead.

I do want to address one hidden elephant in the room, and that is, the ECI report was funded by The Boeing Company, Center for Audit Quality, Deloitte Foundation, Walmart, Louis Berger, Edison International, Lockheed Martin and BP. That alone didn’t deter me from reading it and taking it seriously, especially as some of the results constitute what a litigator might call a declaration against interest: the results don’t seem to be distorted in a way that one might expect a reliance on corporate funding might distort them. In fact, the statement “the state of ethical cultures across the country remains unchanged”– is yet more evidence that self-regulation has failed. And that larger conclusion to me is more powerful precisely because it’s emerged from data collected for a corporate-funded report.

In the last section of the study, the ECI throws the ball back to corporations, either to create an ethics and compliance program if none existed, or to strengthen existing programs.

But reliance on self-regulation isn’t cutting it when one focuses on the rate of increase in retaliation– especially as related to the rate of reported misconduct. That suggests there’s obviously much more that needs to be done at the regulatory level– and by that I don’t mean the SEC taking another undeserved victory lap when it announces the occasional whistleblower’s award. I know, I know, the inadequate state of regulation is a feature, not a bug. Such regulatory action isn’t going to occur anytime soon, and certainly not in the current political climate. But that doesn’t mean one should stop observing, and pointing out the obvious.

Excellent work there, Jerri-Lynn. Your summary appears to be spot on and is troublesome with regard to how that “self-regulation” thingy is workin’ out for us.

Beautiful writing. On a very important topic.

Thanks so much for being on top of this.

I find that all quite sad. Whistleblowing is about getting yours not about correcting deviant behavior. The inference is that people will not do it without reward; they don’t really care about the morality of their employers, just the money. Isn’t that a sad commentary on the collapse of society in America?

This is uncharitable. Less pessimistically (about whistleblowing individuals), the high payouts are probably necessary for employees to be willing to take the risk of immolating their careers by whistleblowing.

This of course is still pessimistic (realistic) in the sense that it is the employers (and management employees) and broader society which are morally deficient.

Whistleblowing is about doing the right thing when everyone else is doing something awful (or is too afraid not to do that thing).

I would like to see the suicide rate of whistleblowers compared to the average. My guess is that it’s an order of magnitude higher.

No…Whisleblowing is not about getting cash for ones self…… not even close.

It’s about stopping activities that do great harm to others, anotherwords, stoping fraudulent, criminal and civil wrongs.

If you can’t conduct a clean business then you ought to look at mirror for the problem, but then those who participate in the corruption find it impossible to be employable otherwise.