By Pirmin Fessler, Senior Economist, Austrian Central Bank and Martin Schürz, Head of Monetary Unit, Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Economic Analysis Division. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

As early as 1900, German sociologist Georg Simmel identified a central feature of wealth in his seminal work The Philosophy of Money. Simmel writes about the superadditum of wealth for the rich, namely that a great fortune is encircled by innumerable possibilities of use, as though by an astral body.

n 1926 Scott Fitzgerald published the short story “The Rich Boy.” The story begins with the sentences “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” Ten years later, Ernest Hemingway — a friend of Fitzgerald — wrote in “The snow of Kilimanjaro”: “He remembered poor Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of (the rich) and how he had started a story once that began ‘The rich are different from you and me. And how someone had said to Scott, yes they have more money.’”

The most popular contemporary form of analysis of wealth inequality takes this Fitzgeraldian view. It analyses wealth in a one-dimensional way: it separates a group of the rich from the rest, defined by having more wealth than the others. The “rich” are typically considered to be the group of the wealthiest top 10%, top 5%, or top 1%. The share of this group in total wealth is estimated and compared across countries and time.

This one-dimensional approach to analyzing wealth inequality follows a pure counting logic of more versus less. The simple counting approach is agnostic with regard to the fact that differences in quantities might imply qualitative changes with regard to the prospects that come with wealth. Further, the approach ignores the fact that the meaning of wealth levels and wealth shares also depend on the context in society at a certain point in time. In particular, pension systems and other institutions of welfare states are different over time and across countries.

The agnostic stance stands in contrast to normative interpretations of the statistical results. Interpretations are often based on implicitly assumed links to power and production relations; the OECD argues that higher inequality drags down economic growth and harms opportunities, and specifically that high wealth inequality limits investment opportunities and therefore growth (OECD 2015). Piketty (2013) argues for a tax on wealth to be implemented to slow down the process of wealth concentration for the sake of democracy. However, the share of a percentile itself does not allow normative interpretations, neither positive nor negative.

Piketty himself is aware of these problems and argued several times for a broader approach including social and economic relations between different groups in society. He has made strong claims (2013,2017) in favor of a relational and multidimensional approach to the analysis of wealth inequality.

A multidimensional approach does not focus only on overall wealth (Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission, 2009), but takes into account other related variables, such as income from wealth. A relational approach does not focus only on the rich or the poor, but instead on the whole society and the relations of different groups within society.

As early as 1900, German sociologist Georg Simmel identified a central feature of wealth in his seminal work The Philosophy of Money. Simmel writes about the superadditum of wealth for the rich, namely that a great fortune is encircled by innumerable possibilities of use, as though by an astral body.

In the spirit of Georg Simmel’s remarks on the huge possibilities that come with high wealth, we are currently engaged in developing such an approach to analyse wealth inequality. We introduce different functions of wealth right from the beginning into a class based analysis of wealth inequality (see our preliminary paper “The Functions of Wealth: Renters, Owners and Capitalists across Europe” presented at the WID conference in December 2017: http://wid.world/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/084-Functions_of_wealth-Fessler.pdf). This allows us to base the analysis of wealth inequality in a setting which is both relational and multidimensional. We use household survey data, since register-based data — which are often used to estimate top shares — hardly allow for such an endeavor.

The work most closely related to ours – we are aware of – is a recently published book authored by the French sociologists Cédric Hugrée, Étienne Penissat, and Alexis Spire. Both approaches share the European-wide perspective on social classes (Hugrée et al 2017).

Towards the Functions of Wealth

Looking at the wealth distribution alone provides an incomplete picture of the social implications of wealth inequality. Additional insight can be gained by classifying households based on decisive functions of their wealth holdings. A focus on functions of wealth allows a coherent organization of the data justified by social stratification right from the outset. In other words, it makes implicit judgments explicit.

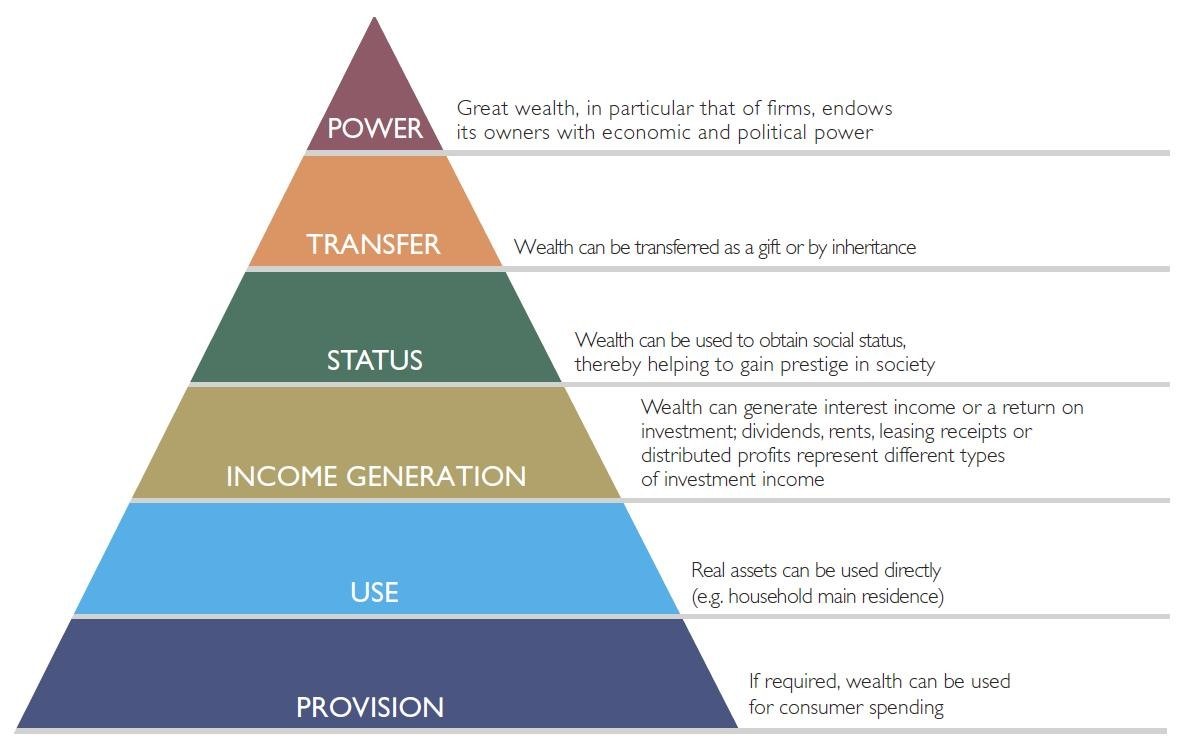

Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of functions of wealth across the wealth distribution. The more wealth one holds, the more functions are potentially available to them.

Figure 1: Functions of wealth

At the very bottom, households save for all kinds of precautionary reasons, such as the necessary replacement of a washing machine, but also for unexpected unemployment, sickness, or for education. The necessity of this precautionary wealth accumulation depends heavily on existing welfare state policies and the degree to which these policies insure these contingencies of life in an organized way (Fessler & Schürz, 2015). With increasing wealth, the function of use becomes more prevalent. The main item in household wealth, home ownership, is used and therefore provides non-cash income. More wealth in real or financial wealth might allow households to generate substantial cash income. A subgroup of such households at the very top, households with very high wealth of a certain form might be able to exercise power. Recent research shows that especially at the very top of the distribution, the power to directly influence democratic outcomes is rather important (Ferguson et al 2016).

We start from those households whose wealth can fulfill all three main functions: they have resources for precaution, own their home to generate non-cash income, and have self-employed business and/or rent out further real estate to generate cash income. Because these households generate cash and non-cash income from their wealth holdings, we call this group the capitalists. A second group owns their main residence in addition to precautionary savings. They have non-cash income in the form of imputed rents from owning their home, but do not have substantial cash income. These we call the owners. Third, some people only have savings for precautionary reasons and have to pay rent to the capitalists who own their homes. For this third group, wealth mainly has a precautionary function. These are the renters.

Relational Approach Aligns Well With the Wealth Distribution

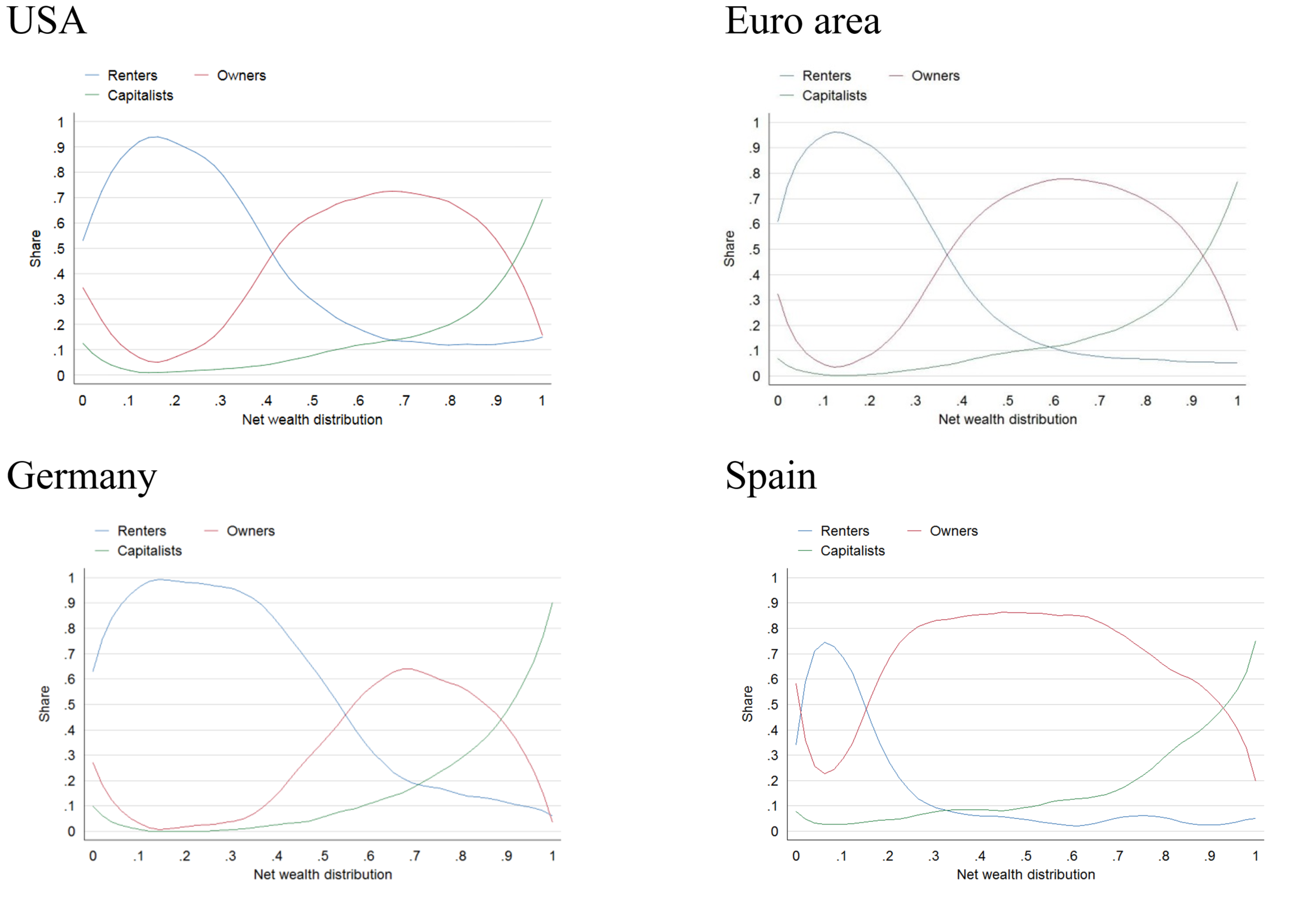

Bringing these definitions to the data, we find renters in the bottom, owners in the middle, and capitalists at the top of the wealth distribution. Theoretically, households should be indifferent between renting or owning a house under the standard assumptions in economic theory (strict life cycle preferences, no bequest motives, no credit constraints, rational behaviour etc.). In practice, however, all of the conditions of the standard model are violated. Households care about bequests (both as recipients and as givers), they face borrowing constraints (like downpayment requirements), they show less-than-fully-rational behaviour and in addition the tax system often favours ownership vis-a-vis renting. Figure 2 shows the resulting estimates for renters, owners, and capitalists in the US and the Euro area. Note that the figure for the US cannot be found in the paper presented at the WID but will be included in an extended version or the paper we are working on currently. The lines can be interpreted as the probability that a household at a certain point of the wealth distribution with a certain level of wealth is a renter, owner, or capitalist.

The same pattern emerges in all countries of the Euro area. In figure 2, we show Germany and Spain as rather extreme cases to illustrate how the general pattern holds while the points and the degree to which a certain class dominates a certain area of the wealth distribution can differ substantially.

Figure 2: Renters, owners and capitalists in US and the Euro area

The country patterns likely differ due to institutional settings, tax law, history, the welfare state, and many other conditions. As an example, different policies for owner-occupiers target different groups in different countries. The bottom 50 shares of wealth in one country can consist mostly of renters’ precautionary wealth while it can comprise mainly of the homes of owners in another country.

This demonstrates that percentile and top share analyses and comparisons might be misleading, as the functions of wealth and corresponding relations between social groups are different across the wealth distribution in different countries.

A Multidimensional View of Inequality

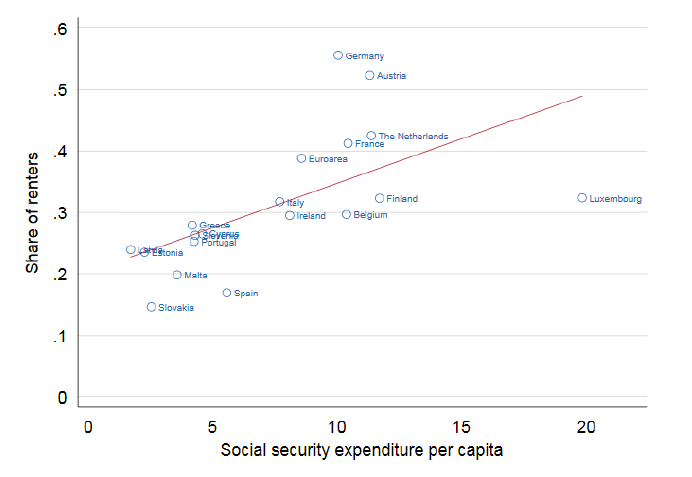

The welfare state strongly shapes the meaning of asset ownership for renters and owners. Figure 3 shows how the share of renters is positively correlated with social security expenditures across countries. In countries with higher social security expenditures, there are typically also larger degrees of state-organized pension systems, housing subsidies, social housing, and regulated rental markets. In turn, a larger share of renters often goes along with smaller household sizes, as it is easier for younger people to form their own households and easier for the elderly to sustain their households for a longer time.

Figure 3: Share of renters and social security expenditure

The form of income plays a major role in the definition of our typology. Capitalists use their capital via businesses to generate capital income. In addition, or alternatively, they use their real estate wealth to get rental income. Renters pay their rent from their labor income, whereas owners use their homes to live in, generating an imputed rent (which is not included in our definition of gross income). Income — and not wealth — is the decisive economic variable for renters. Thus, analyzing the wealth distribution has to be done in a multi-dimensional way. Instead of comparing capital-to-income ratios across countries and over time, it might be worthwhile to zoom in and find the common patterns inside contemporary societies.

Regardless of large country differences in the share of renters, renters’ median yearly gross income is (mostly substantially) larger than their median net wealth. In most cases, yearly income is about 2-5 times larger than net wealth, which translates to capital/income ratios of 0.2 to 0.5. For owners, that relationship is turned around. Capital-to-income ratios based on medians for owners are well above 5 — and they go up to 13 for capitalists.

Justification of Wealth Inequality

In economics, there seems to be a kind of consensus that an increase in wealth inequality might be bad. The OECD claims that it is bad for growth and (investment) opportunities; Piketty argues that it harms democracy.

There is a long tradition in philosophy starting with Plato and Aristotle of normative substance that deals with wealth explicitly. In Plato’s “Republic”,wealth is judged in moral terms. Plato claims that large levels of wealth have negative consequences for individuals and for \ society and that only moderate wealth enables a moral life. Otherwise, he explains, two parallel cities exist, “the city of the poor and the city of the rich”in one place.

In his later work “Laws,” Plato stresses that wealthy citizens feel that their wealth is more valuable than their virtue. Thus, they believe that they do not need to follow the laws that would create social harmony. Plato´s prescription is to cap wealth for the richest citizens at four times the wealth of the poorest ones.

In contemporary society, moral qualifications in support of and against entrepreneurs exist. Either their economic success is proof of being talented, risk-oriented, or innovative, or it is a sign of their greed and selfishness. Further, evaluations such as the concepts of earned and unearned wealth and the subsequent moral differentiation between self-made millionaires (working rich) and inheritors (trust-fund babies) point towards issues of justification.

Coherent justifications of wealth inequality need a focus on different wealth functions. The functions of precaution, use and power have to be distinguished. It is obvious that meritocratic justifications of the wealth of the rich has to be questioned. Statistical analyses show that there is even a privileged position of capitalists in the inheritance process (see our preliminary paper presented at the WID: http://wid.world/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/084-Functions_of_wealth-Fessler.pdf).

Capital Versus Wealth Debate

A relational and multidimensional approach to wealth inequality contributes to recent theoretical debates on the roles of capital and wealth.

Already during the famous Cambridge (US vs. UK) capital controversy in the 1960s, the main question was one of aggregation. Joan Robinson, Piero Sraffa and others (Cambridge UK) basically argued that the jump from micro to macro, as done by capital aggregation in mainstream theory, ignores more complex economic structures based on power relations and class structures necessary to understand the production process at the level of the society (see Taylor 2015 and Garbellini 2018).

Our approach allows us to distinguish between private wealth as a substitute for public wealth (precautionary wealth), private wealth as a source for non-cash income (housing wealth used), and private wealth as a mean of production generating profit (business wealth and rental income from housing wealth beyond the home). These different forms of private wealth are tied to different classes and accompanying power relations.

As Lance Taylor recently discussed, inequality is driven by the power of capital in relation to workers and how this relationship was transformed over the past four decades (Taylor 2017a and Taylor 2015b). Private wealth must be interpreted in relation to different volumes of public wealth and different institutional settings over time and between countries. These are relevant factors and drivers of the power relations between renters, owners and capitalists. This conceptualization is easily overlooked when just analyzing top shares of private wealth. Today, the role of top incomes in this context is especially difficult to assess because of the role stock buy-backs play in raising executive compensations (see Lazonick and Hopkins 2016). How wealth is used to exercise political power at the very top of the distribution can also be studied by analyzing industry contributions to political campaigns. Ferguson et al. 2018 recently employed such data to analyze this process for the 2016 Presidential Campaign.

Conclusions

Wealth analyses often hide their normative considerations behind statistical presentations of percentiles and top shares. Those who focus on the wealth share of the rich will overlook the rest, missing society as a whole and what it means to be at the top of the wealth distribution.

The heterogeneity of wealth inequality cannot be reflected by a one-dimensional focus on net wealth. We should look instead at structured wealth inequality through the lens of social classes. Such a structure needs to link wealth to its functions, right from the start of the statistical analysis, and base the groups on social relations instead of arbitrary levels of wealth itself. The social structure concerning wealth can be characterized by roughly three classes which align well with the wealth distribution. This alignment holds even if one controls for socioeconomic characteristics used in class analysis such as education and occupation or main determinants of wealth accumulation such as age. A class-based approach has advantages with regard to the measurement and analysis of wealth. However, the main advantage is that implicitly assumed links to power and production relations – which are the foundation of contemporary interpretation of top shares (see OECD 2015 and Piketty 2013) – are made explicit. On top of that, such an approach can be directly linked to questions of justification of wealth inequality and allows us to distinguish between wealth as a means of capitalist production and other forms of wealth.

See original post for references

Conversations about wealth inequality should veer away from graphs and charts; they’re less appropriate to understanding what is going on than e.g. Plato’s moral calculus.

The primary questions are fundamentally moral: the basis of wealth accumulation is its justification based on notions of merit. The rich have “earned” their wealth – to “earn” money is a deeply moral claim about deserts, justice, and the fundamental rights of individuals with respect to each other.

What is interesting to me about wealth is that it relates directly to moral worth – not in a graded way as suggested above, but proportionately. The slightly-wealthy are more morally worthy than the poor, and less than the extremely-wealthy. We can see this clearly along race lines, where whites are able to pass on the inherited wealth of previous generations than blacks or hispanics, thus elevating them in moral terms.

Also, wealth as moral worth is fungible. J.K. Rowling earns her wealth writing books, but is not accorded power merely over further book-writing; her wealth empowers her to buy mansions, fund charities, secure political power, etc. Clooney brags about using his wealth (earned pretending to be various characters in films and television) to surveil Sudanese warlords. The wealthy are accorded blanket power by their wealth which they may exercise in any domain of their choosing – they are *simply* more worthy.

Finally, wealth is, in moral terms, relative, because the command of wealth gives, in simplest terms, the ability to direct productive output. The implication is that the wealthy deserve to be able to direct the effort of others to their own ends, while the poor do not even have the right to determine their own actions.

These moral tenets seem to flow directly from our notions of wealth, but they seem fundamentally at odds with other moral constructions, such as the Enlightenment-era conception of basic human rights and the equality of all human beings. These concepts are enshrined mostly in the guarantee of democratic politics, public education, etc., but the realization of this moral construction was always incomplete, and is eroding rapidly in favor of the moral inequality of wealth.

Personally I feel the moral constructions of wealth are weak fictions that no one really accepts, although we live with them. Few people really believe that any human being is a billion times better than another, despite the fact that the world is constructed to support this kind of deification of the rich.

“should veer away from graphs and charts”

Respectfully disagree.

To understand how completely out of whack both income and wealth distribution are,

it’s essential to convey it with charts and graphs, and they need to be constructed in ways that show

how insane the spikes at the top end are.

Otherwise, many people just don’t believe you or their eyes glaze over.

Only after understanding the reality can one move on to an informed discussion of what to do about it.

My eyes glaze over when I see too many charts. Charts aid in understanding, and they obfuscate understanding. Just a tool. We need to be guided by something else.

As saurabh said above, “The wealthy are accorded blanket power by their wealth which they may exercise in any domain of their choosing”

— this is a delusion that is very strong and deep in society that needs to be counteracted by other values.

Charts and graphs can lie, just as words can.

But their usefulness in aiding understanding might be linked to how a person learns. I am a ‘visual’ person and find that a graph or chart will make more of an impact on me than whole paragraphs of words.

One’s like or dislike of using charts to process information has more to with how one thinks, the kind of analysis that is more innate to some and not to others. I don’t want to use the Left Brain/Right Brain analogy since it has been debunked, but that in a general way is what I mean.

Personally, charts help me process information in that it gives me a visual way to approach it, thus it helps me retain information better, though as the years go on retention seems at times problematic.

Relative wealth comparisons aren’t about who “is better”.

They are about who “has more”. And by “how much”.

I find graphs and charts very useful in thinking about such things. I also just like graphs and charts.

Without real data, however presented, you are just offering an opinion. The poor man’s rigorously argued, logical and rational opinion is easily outbid by the rich man’s self-serving bullshit.

I don’t accept your epistemological prejudices. The presentation of information in charts does not give claims validity; “data” is an ontological imposition on the world, a statement about belief, an opinion. Furthermore the notion that we can understand human society empirically is belied by very simple, elemental human desires like the love between parent and child, or the conviction that hurting others is wrong. These are not empirically verified or verifiable notions, but they are central to much of our lives. Similarly, belief about wealth and who deserves it is not something to be settled empirically, and the longer we seek answers exclusively in graphs and charts the more time we waste not having useful insights on the matter.

There’s a weak assertion here that few would disagree with (that graphs and charts are not the only legitimate way to discuss this subject), but you appear to be making a much stronger assertion (that empirical reasoning has no part to play in understanding wealth).

This latter assertion is dubious. The manner in which currency and prices operate is that they convert more “elemental” judgments of value into precisely quantified data. The best construction I can give to your argument is that overindulgence in empirical reasoning risks valorizing this conflation (of “actual” value with currency-denominated value). If so, point taken, but it doesn’t follow that the only solution is to refuse entirely to think about the sort of quantitative logic that is reinforced by money – what would instead make sense is a study of the interplay between this kind of logic and other moral claims.

> Furthermore the notion that we can understand human society empirically is belied by very simple, elemental human desires like the love between parent and child,

“I refute it thus” [kicks baby].

Also, in that last sentence, isn’t “exclusively” doing rather a lot of work?

slogan attributed to the Medici, in paraphrase: “wealth to attain power, power to protect wealth”.

As long as there is this kind of disparity in incomes, (see https://www.themaven.net/mishtalk/economics/walmart-ceo-makes-1-888-times-median-worker-take-home-pay-anyone-see-a-problem-rZ8-ACgJ40Cx0iQjR0zDsA/), how will there not be wealth inequality. There should be a semblance of a relationship between the incomes along the hierarchy and the top. As long as the top management is NOT WILLING to do this, there will never be an end to wealth inequality.

I’d say that the Clintons are proof-positive that first you get power and then the money will come in…. Macchiavelli knew that, power comes first and money comes second.

Anyone analysing it the other way around might want to explain who’ll end up with all: a robber with a gun (power) or the rich unarmed person with money? Will the rich buy the gun for some of the money? Will the robber get all the money and keep the gun? Or will the rich person buy the gun and take back the paid money using the power of the gun?

Any politician who claims that money gets you power is simply stating that he/she is for sale and anyone giving that particular politician power will see the power being sold.

I respectfully disagree. Money brings power, but it’s not the only source of power. The Clintons had (have?) political power, they used it to get money because they rightly understood that it would bring them the economic power that comes with it. More power, and power all-year-round as political power fades.

But yes, politicians stating, like Mick Mulvaney just did that money is power is indeed asking for bribes.

Maybe a working definition of power is the ability to reward friends who will support you and to punish your enemies.

I see no justification for giving primacy to either wealth or power. Wealth may be transformed into power, but is not always. And power may be transformed into wealth, but is not always. These are two different, but related things. There is nothing readily discernible in them that requires the transformation to be one way. Some people seek power. Some people seek wealth. And some people seek both and perhaps find a certain synergy in doing so.

I think people with very much of either are aware that they can trade one for the other and so satisfy their individual cravings for both in a balance that has more to do with personal psychology than anything else. That some people took the path of power to achieve wealth does not “prove” in any way that other people do not take the path of wealth to achieve power.

Plato saw the identity link between the desires for power and for wealth as lying in their shared elements of “competitiveness and ambition” – this he called “pleonexia.”

In the USA the wealthy elites also control the guns (the military as well as local law enforcement). The Clintons only acquired their power due to their wealthy backers. Money is power… it takes money to make war or to put someone in the white house.

> > Macchiavelli knew that, power comes first and money comes second.

> I respectfully disagree. Money brings power, but it’s not the only source of power.

Maybe it’s a yin and yang, systemic, cyclical M-C-M′-style of thing…

Please, do not let anyone, especially the NC commentariat fall prey to the urban legend that Hemingway said that to Fitzgerald.

A fuller discussion can be found at:

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Talk:F._Scott_Fitzgerald

In actual fact:

The UK aristocracy show how long you can stay at the top of society.

Some can trace their history at the top of society back to the Battle of Hastings and some back to Charlemagne.

Once acquired, a fortune can last a very long time.

The landed gentry’s interests were always directly opposed to those of the capitalist class.

“The interest of the landlords is always opposed to the interest of every other class in the community” Ricardo 1815

High housing costs have to be covered in wages raising costs to business and reducing profits.

Disposable income = wages – (taxes + the cost of living)

Employees want more disposable income (discretionary spending).

Employers want to pay lower wages for higher profits.

High housing costs are like a tax on the economy.

The minimum wage is set when disposable income equals zero.

The minimum wage = taxes + the cost of living

US businesses want a low minimum wage, but haven’t realised high housing costs are part of the problem.

The early neoclassical economists hid the problems of rentier activity in the economy by removing the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income and they conflated “land” with “capital”. They also took the focus off the cost of living, which had been so important in Classical Economics.

To get the full picture look at all three groups like Ricardo used to do.

From Ricardo.

The labourers had before 25

The landlords 25

And the capitalists 50

………..

100

Ricardo kept an eye on how the pie was divided between the capitalists, the rentiers and labour.

Joseph Stiglitz has recently done something similar in the US.

The share to labour is going down.

The share to capital is going down.

The share to rents is going up.

“Income inequality is not killing capitalism in the United States, but rent-seekers like the banking and the health-care sectors just might” Angus Deaton, Nobel Prize Winner

He should have been monitoring the situation like Ricardo before it got this bad.

This is what happens unseen with neoclassical economics and its happening across the West.

Showing us that sometimes the apocryphal story is more interesting than that factual one. ;-)

‘Once acquired, a fortune can last a very long time.’

Only, in the United States, it doesn’t. It is difficult to find a millionaire descended from a Robber Baron, or at least its hard to find one who didn’t make their own money. It’s different in Europe. There are still rich Fuggers.

https://www.researchaffiliates.com/en_us/publications/journal-papers/359_the_myth_of_dynastic_wealth_the_rich_get_poorer.html

I don’t buy this for a minute. First of all, concentrating on only the wealthiest 400 families leaves out an enormous and generally much more economically stable group of families who aren’t quite as rich.

Second, it ignores the effect of the ‘family business’, where younger generations stay in the same industry or even the same company and continue to preserve and increase their wealth.

Another factor conspicuous by its absence is that as income inequality has grown, those earning their fortunes more recently have made larger ones than those whose forebears did. The Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos of the modern world have certainly bumped other still plenty wealthy people off the list. Did they get poorer or did the bar to be on the list get raised?

Once the larger population of Tyler Mathisaen’s ‘Richistan’ is taken into account, the picture changes rather substantially.

Thank you Yves for this post. It is a very good contribution against neoliberal ideology. This has called my attention for further discussion:

Understanting this gives good comprehension on most political maladies these days: this explains way the neoliberal narrative (that ignores this) prevails, explains foreign interventionism, the push for those pesky “trade” treaties that further exacerbate the power of the powerful. Also explains part of the populist responses: “brexit” as a protest against the very powerful EU institutional machinery, independence movements in Catalonia, Scotland etc. I feel that in smaller states, with less complex institutional structures, it migth be easier to exert democratic control over the positions of the powerful and their relations.

“They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made…” (F. Scott Fitzgerald, ‘The Great Gatsby’, Penguin Modern Classics edition, p. 170)

Looking behind the corporate veil at the outstanding issues of our time, from climate change to endless wars to financial collapse to “Tale of Two Cities” social divisions to deteriorating infrastructure and public education to fraud and corruption to limited economic opportunity for young people, etc., it seems to me that “Tom and Daisy” really haven’t changed all that much in terms of their exercise of the power that comes with wealth. And the rest of us are left with the results of their massive policy failures; regardless whether they stem from myopic vision, raw greed, casual or willful negligence, or other psychological drivers.

I agree with Thomas Piketty’s observation cited in the article hat extreme wealth inequality harms democracy. We see it play out in every election cycle and subsequent policies. And it has become clear that harm to representative democracy has been deeply damaging from a very broad range of perspectives.

THIS. As long as wealth is not held accountable for the destruction it visits on the rest of society, democracy and society will suffer. Let it go on long enough and civilisation will, too.

There is no moral construction that adequately justifies the notion that greater wealth equates to greater morality. That’s just an age old excuse power uses to justify itself.

Will society need to collapse (lost wars, economic depression, civil disorder, etc) for us to learn this lesson again? The only ones who seem to be learning from history are those seeking to preserve their wealth and power from the forces that brought it down in the past, thereby making the underlying inequities more extreme and therefore more dangerous.