Bill Mitchell has a short (for him), deadly post on what a bust QE has been in Japan.

We’ve pointed out that the Fed’s retreat from QE appears to be due at least in part to the fact that the central bank recognizes belatedly that it didn’t achieve its intended aim of stimulating the real economy. On one level, the Fed sorta knew that, since monetary stimulus does not lead to more demand in the economy. Only more fiscal spending, aka deficits, will do that.

What QE can do is provide a wealth effect, which will lead consumers to spend more. But the wealth effect works to a degree with housing wealth, and not much with financial assets. Moreover, the people who will spend more are people who already by definition have assets. They already have a weaker propensity to marginal spending than less well off people, so the wealth effect is at best an inefficient way to try to induce more expenditures. And those rich people could engage in spending that does little or nothing in the way of adding to GNP, like going on vacation abroad or buying collectables (as in pushing other asset prices up).

And on top of that, by lowering long-term bond yields, QE reduced income to savers such as retirees, since as their older bonds matured, they could replace them only with lower-income-producing assets. Ed Kane of Boston University estimated the cost of super low interest rate policies (which admittedly consists of more than just QE) lowered income to savers in the US by $300 billion a year. So even though goosing housing prices via lowering mortgage interest spreads (an explicit aim of QE in the US, and there was probably also more net spending as a result of mortgage refinancings lowering costs homeowners) may indeed have produced more spending, it was offset by the reduction in interest income for all savers.

Even worse, economists who ought to know better, particularly monetary economists like Ben Bernanke, believe in the loanable funds theory. In layperson terms, that’s the notion that banks lend from pre-exisitng savings. Keynes and then later Nicholas Kaldor disproved it; there’s also plenty of empirical work that show that lending precedes savings, and the MMT proof of that is to work through T accounts and show how loans create deposits. The Bank of England has not only confirmed the view, but thought it important enough to put out a primer for the general public as well as a video.

However, if you believe that loanable funds bollock, you believe related silly ideas, namely, that if you put money on sale, businesses will borrow and run out and expand. Any prudent businessman will tell you that they add to their overheads (which is what “expanding” amounts to) only if they see enough potential profit to justify taking on the additional risk. The cost of money can constrain going into new markets, but making money cheap won’t lead entrepreneurs to launch a thousand new ventures. The exception? In businesses where the cost of money is the one of the biggest cost of the product or service….such as for leveraged speculators.

Mitchell works through how Japan, which engaged in QE in a more spectacular manner than anywhere else, demonstrated that it doesn’t work. As an aside, Mitchell also dismisses the scaremongering over QE, that it will bankrupt the central bank (which is not possible in this scenario; a central bank can always pay any obligation in its own currency) or that terrible things will happen when the central bank undoes QE (which Mitchell points out is nonsensical; the central bank does not have to do anything; it can let the bonds it bought mature or continue buying bonds to keep its balance sheet at the same size if it so chooses).

In Japan, the central bank pursued QE to increase inflationary expectations, with the hope that that would then induce Japanese citizens, who are remarkable savers, to start spending more. Frankly, having lived through the later 1970s, when inflation actually was high enough to induce people to spend sooner if they had spare cash, the idea that lowering interest rates could be thought of as creating inflationary expectations was bonkers. That’s sending a loud and clear deflationary signal. What is the smart stance in deflation? Hold cash, cash equivalents, and high quality bonds. You hold back on spending because things may/will be cheaper later.

I suggest you read Mitchell’s post in full. Key bits:

On April 20, 1018, the IMF presented its – Asia and Pacfic Department Press Briefing – in conjunction with the release of the April 2018 World Economic Outlook and the upcoming (May 9, 2018) release of its Asia and Pacific Regional Economy Outlook. The Deputy Director of the Asia and Pacific Department, one Odd Per Brekk, told the audience that Japan should continue its Quantitative Easing (QE) program and maintain transparency in its purchase volumes so as to ensure the strategy to accelerate the inflation rate up to the 2 per cent target is achieved….

In other words, the IMF was urging the Bank of Japan to continue to maintain its huge “monetary stimulus” in order to increase the inflation rate, which is languishing at around half the Bank’s stated target…

n the December-quarter 2017, total assets stood at 94.5 per cent of GDP (and JGB holdings were 80.2 per cent of GDP).

Why this particular statistic matters is beyond me but apparently the “critics” think it matters.

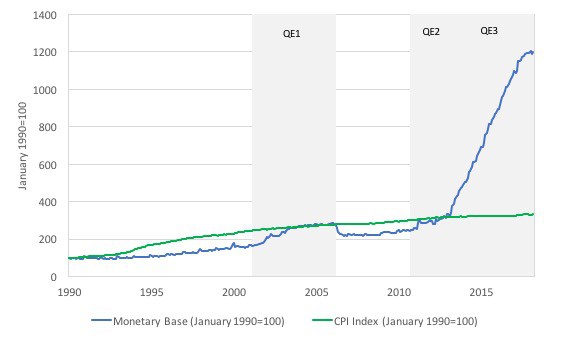

The point of this blog post is to emphasise that it doesn’t matter one iota and that it rapid acceleration since the Bank of Japan started buying JGBs in large volumes in order to increase the inflation rate demonstrates how ineffective monetary policy is in influencing the path of the inflation rate, despite the massive increase in central bank assets…

The overwhelming conclusion is that there is no relationship between the evolution of the monetary base (driven by the Bank’s purchases of JGBS in large volumes) and the evolution of the inflation rate.

One could argue that the reversal of QE1 revealed a lack of commitment by the BOJ to really drive the inflation rate up. My assessment is that QE doesn’t work whether it is extended for lengthy periods or not.

The reversal that followed the introduction of QE2 just reduced the monetary base (and the total assets held by the BOJ).

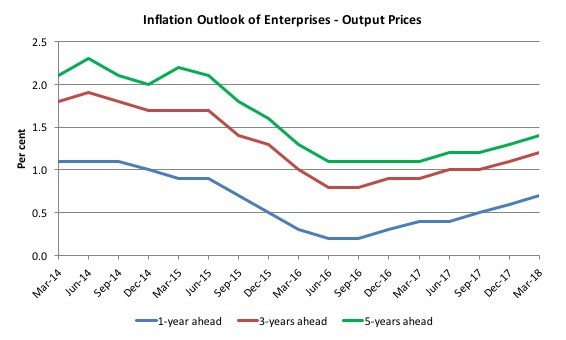

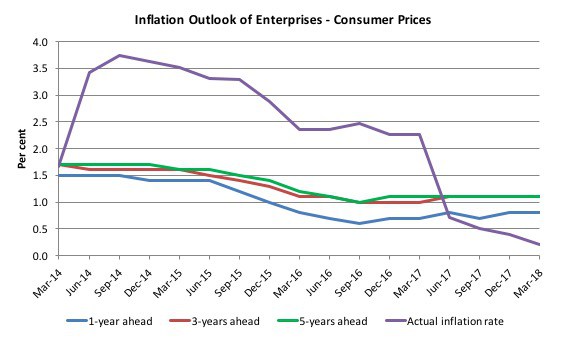

The latest data on inflation expectations is also indicative that the QE policies are not having the desired effect…..

The following graph is taken from the – Tankan Summary of “Inflation Outlook of Enterprises – the latest data being released on April 2, 2018, covering expectations up to March 2018.

Firms are asked to assess the future price movements in output prices and consumer prices.

The first graph shows the outlook for output prices – 1-year ahead, 3-years ahead and 5-years ahead.

While the expectations have risen in recent months, that is more the result of increased output growth. In the early periods of QE3, the expected inflation rate for output prices fell sharply.

The second graph shows the outlook for consumer prices – 1-year ahead, 3-years ahead and 5-years ahead. It also includes the actual inflation rate (Purple line).

Again it is hard to see any substantial movement in consumer price expectations.

Bill Mitchell should pat himself on the back and conclude, “QED.”

If the central banks had loved their regulatory power as much as their power to conduct QE, I suspect we would be in a more stable and saner place.

Let’s rent out the helicopters, and start dropping cash out of them.

Giving money to people, rather than banks, and the money will be spent.

What is the problem with the economics they used for globalisation?

The 1920s roared with debt based consumption and speculation until it all tipped over into the debt deflation of the Great Depression. No one realised the problems that were building up in the economy as they used an economics that doesn’t look at private debt, neoclassical economics.

That’s it, it had the same problem it’s always had; it doesn’t look at debt.

The problems come from debt and the solutions require an understanding of debt, banks and the money supply.

Houston, we have a problem.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

The “black swan” was obvious all along and it was pretty much the same as 1929.

1929 – Inflating US stock prices with debt (margin lending)

2008 – Inflating US real estate prices with debt (mortgage lending)

What’s the difference?

We still have a huge debt overhang and the repayments on that debt will keep dragging the economy down just like it did in Japan after its 1980s real estate boom.

Richard Koo explains (he has had decades to study it and knew what would happen after 2008 in the West).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Kuroda became head of the BoJ, but had no central banking experience and embarked on QE to infinity (17 – 19 mins. in video). William White (BIS, OECD), Richard Koo and Shirakawa (previous head of the BoJ) don’t know what Kuroda is doing.

To understand Richard Koo you need to understand where the money supply comes from.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

When banks issue loans they create money, when you make repayments on bank loans this destroys money.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

As far as I know there is only one book in existence that covers it “Where does money come from?”

https://larspsyll.wordpress.com/2018/04/24/the-loanable-funds-fallacy-3/

The values for CPI in the graph seem to imply a much higher rate of inflation than that discussed.

Prices doubled from 1990 to about 1997 and went up 50% (of the 1997 level; 100% of the 1990 level) from 1997 to about 2013.

2% inflation gives about a 15% rise over 7 years and 29% over 13 years.

So the graph seems to show far higher inflation than the sub-2% I have been reading about for decades now.

There is something I am missing here?

I am sure that our commentariat has the answer.

Good catch. Something is definitely wrong. Per the E-stat website that hosts Japan’s data, the CPI in January 1999 was 100.1. The CPI now is 101.

I think you are confusing inflation rate and price level. My interpretation of the chart is that inflation rose from 1% to ~3% over the whole period. So less than a doubling of prices.

This article points out the worst failing of what occurs when MMT is “vulgarized.” Its threefold division into government, domestic private and international sectors neglects to break the domestic sector into FIRE vs the rest of the economy.

QE people may “love” MMT to the extent that it enables them to bail out banks and inflate asset prices. But of course, the whole point of MMT is to revive the DOMESTIC economy (in a rather Keynesian way, to be sure).

The economic model that I have outlined in my books (and which Dirk Bessemer cited in his FT article on those of us who explained why the 2008 crisis had to occur when it did) does break down the private sector into finance (and FIRE as a whole) vs. the rest of the economy.

That is what is anathema to the vested interests.

Mister Hudson.

If I might, does it all square the functional finance vs sound finance quagmire. Additionally, when dealing with the payment system via MMT was it not the political systems responsibility to effect Keynes [nothing to do with Keynesian] policies.

Cheers.

Haven’t the Japanese learned anything from us? Just change the way they measure inflation so as to show a spike in the numbers where necessary. Just like we manipulate our unemployment figures /s

QE and negative real interest rates in Japan, as in the EU and the US, haven’t failed their policy makers. They have been a resounding success in terms of their real policy objectives, which was to facilitate a gigantic transfer of wealth to a few. How do you spell “Carry Trade”; “Foaming the Runway”; “Rising Financial Asset and Real Estate Prices”; “Speculative Debt Leverage” for corporate stock buybacks, CEO options maximization, private equity leveraged buyouts, and massive dividend payouts that have led to concentration of wealth, defunding the middle class politically, and extreme inequality? Perhaps a suggested title for another book might be “QE-conned”

In addition to the $300 billion per year lost under this policy by savers that Yves mentioned in her into to this post, the hidden costs in terms of declining productivity, lost purchasing power, reduced demand, and declining productivity have been enormous. As a graphic from Bianco Research back in mid-March on zombie companies communicates this development visually:

https://twitter.com/LizAnnSonders/status/975739797733068800

The Japan I knew back in the 80’s and early 90’s was an amazing place in that it was a ‘cash & carry’ country. It seemed the majority of transactions were done with do re mi. Haven’t been back so I couldn’t tell you how credit/debit cards wormed their way in, as they must’ve.

Don’t know much about how their QE was doled out, but certainly one thing in QE’s favor here was the idea that the general public never really saw way too much money out there chasing things to buy-aside from say housing bubble part deux, it was mostly on the down low, cyberinflation hidden away by the mouse clique.

Nope. Still a cash and carry country which is my type of country too. Was just there last year.

Is QE a failure in Japan? Maybe. What’s the goal? Just to have higher inflation or growth?

Let’s say that it’s indeed a failure based on some goal, does not mean Japan itself is a failed country. And I think it’s important to point that out because that country is just so amazing in so many ways compared to America or anywhere really. Superlative public transport, amazing food (Tokyo has the most number of Michelin stars of any cities in the world, with Kyoto second, and Osaka fourth) and not just Japanese food, great service culture, incredible cleanliness, etc, etc.

I have no doubt that someday their debt will cause the economy to tumble, but the Japanese will get through it better than most countries will. There will not be any great societal chaos or anything. Can’t say the same for America, Europe or even China.

Is Japan perfect? No, but I think people underestimate its resiliency.

In closing, I probably sound like a Japanophile, and I am, heck I am studying Japanese right now, but I’ve traveled all over the world, and it’s only Japan that would often make me think: why can’t we have that, and that, and that back home here in America? I live in San Francisco, the supposed tech capital of the world, and I work in tech, but darn, you don’t see any of that tech in public. Public transportation sucks, everything looks dirty (and they are), internet connection is sketchy (AT&T), people are rude, etc, etc. Darn, I need to get out of this place.

Can’t we just go back to the old days when savers were rewarded with interest rates higher than the inflation rate and speculators had to cough up hard collateral before being allowed to gamble with money? Getting a bit tired being punished for having some money that I am not willing to throw to the tender mercies of the stock and bonds markets.

On the other hand, the various central bank QEs probably did stop the deflation and Minsky moments that the Austrian economy believers thought were coming. They never imagined that the Central Banks would create 10s of trillions of dollars. Why do you think the Powers That Be picked Bernanke to become the head of the FED right before the Greater Financial Recession. I imagine this stopped the ice nine theory of Jim Rickards from happening (total liquidity lockup). So there are zombie companies kept alive and stock markets inflated along with other asset types giving the semblance of recovery – the real economy just sort of muddled through since nothing was fixed. I would imagine when the next whatever that triggers a major downturn happens that the economic situation will be a magnitude worse than 2006-8,