We pointed out in an earlier post on the growing concerns about trade that “free trade” has worked out well for those on the top of the food chain and not well at all for those at the bottom. In other words, when the press depicts less educated workers as stupid for favoring tariffs, they are conveniently ignoring the fact that “free trade” has been a big weapon used successfully against them in a class war.

We’ve repeatedly pointed out that in a lot of industries, offshoring and outsourcing did not lower total production cost, particularly when you factor in the risk of a more rigid production system and the lost of critical manufacturing know-how. However, it was quite effective in transferring income from direct factor labor to the managerial classes.

That does not mean that tariffs, or more accurately, tariff brinksmanship to pressure China to make concession, will help them. But they are correct to recognize that the changes of the last two decades haven’t helped them and to want something different.

And it is also not crazy to recognize admitting China to the WTO despite it not meeting the entrance criteria was a big accelerant to the decline of manufacturing jobs. Key sections from a 2017 Wall Street Journal article, How the China Shock, Deep and Swift, Spurred the Rise of Trump:

What happened with Chinese imports is an example of how much of the conventional wisdomabout economics that held sway in the late 1990s, including the role of trade, technology and central banking, has since slowly unraveled….

Both presidential candidates aimed much of their criticism at 1994’s North American Free Trade Agreement, which boosted imports from Mexico. Even then, though, the real culprit was China, economists now say.

Many U.S. factories that moved to Mexico did so to match prices from China. Some of the new Mexican factories helped support U.S. jobs. For example, fabrics made in the U.S. are turned into clothing in Mexico for sale globally by U.S. companies….

A group of economists that includes Messrs. Hanson and Autor estimates that Chinese competition was responsible for 2.4 million jobs lost in the U.S. between 1999 and 2011. Total U.S. employment rose 2.1 million to 132.9 million in the same period.

Note that this recap neglects to factor in population growth. The jobs to population ratio was 46.9% in 1999 versus 42.7% in 2011. Adding back those jobs lost to China wouldn’t have brought employment back to 1999 levels. relative to the population, but remember we also had the crisis, plus the earlier Boomers were starting to retire, so that would reduce somewhat the size of the pool interested in working.

And in an Institute of New Economic Thinking panel last October, Berkeley economics professor Brad DeLong explained how the Ricardian fairy tale that is drummed into those who have some contact is unrealistic and a more accurate view of liberalized trade shows it favors the rich:

In that case, we cannot escape the conclusion that comparative advantage is the ideology of a market system that works for the interest of the wealthy. For comparative advantage is the market economy on the international scale, and the market economy is, via the Negishi weights that it assigns to the social welfare function that it actually maximizes, is a collective human device for satisfying the wants of the well off, and the well off are those who control the scarce resources that are useful for producing things for which the rich of the world have a serious jones.

Pia Malaney is Co-Founder and Director of The Center for Innovation, Growth and Society (CIGS) and Senior Economist at the Institute for New Economic Thinking, pointed out that Serious Economists understood the costs of more open trade even though they pretended not to:

Specifically, as most of you probably know, the Samuelson-Stopler theorem would give you good reason to expect that less educated workers in the US would take a hit with more open trade. As Harvard economics professor Dani Rodrik wrote in 2008:

The Stolper-Samuelson theorem is a remarkable theorem: it says that in a world with two goods and two factors of production, where specialization remains incomplete (plus a few more technical assumptions), one of the two factors–the one that is “scarce”–must end up worse off as a result of opening up to international trade. Not in relative terms, but in absolute terms. But the theorem is also quite limited in its applicability. It applies only to a case with two goods and two factors, and so its real world relevance is always in question.

But there is a version of the theorem that is remarkably general and powerful. It says that regardless of the number of goods and factors, at least one factor of production must experience a decline in real income from trade as long as trade induces the relative price of some domestically produced good(s) to fall (and as long as the productivity benefits from trade are restricted to the traditional, inter-sectoral allocative efficiency improvements, about which more later). All that this result requires is a very mild assumption, namely that goods be produced with varying factor intensities (i.e., use different combination of factors). The stark implication is that someone will lose, even if the nation as a whole becomes richer…

The theorem does not identify who exactly will lose out. The loser in question could be the wealthiest group in the land. But if the good in question is highly intensive in unskilled labor, there is a strong presumption that it is unskilled workers who will be worse off. And before you curse economic theory, note that this is really accounting–not economics at all.

Rodrik goes on to argue that this might not be as absolute as it seems, since if manufacturers could increase total factor productivity in response to import competition, they could afford to preserve or even increase worker wages even if the prices for their products fell. But Rodrik pointed out that analysis of firm-level efficiency was pretty dodgy, and you could see the same results by the virtue of the least efficient firms going out of business, which would still hurt overall employment. Moreover, as we pointed out back then, companies were crimping on worker pay even before the crisis. The early 2000s recovery saw labor get a markedly lower share of total income growth than in any post-WWII expansion. And the proportion going to profits versus compensation got even worse after the crisis.

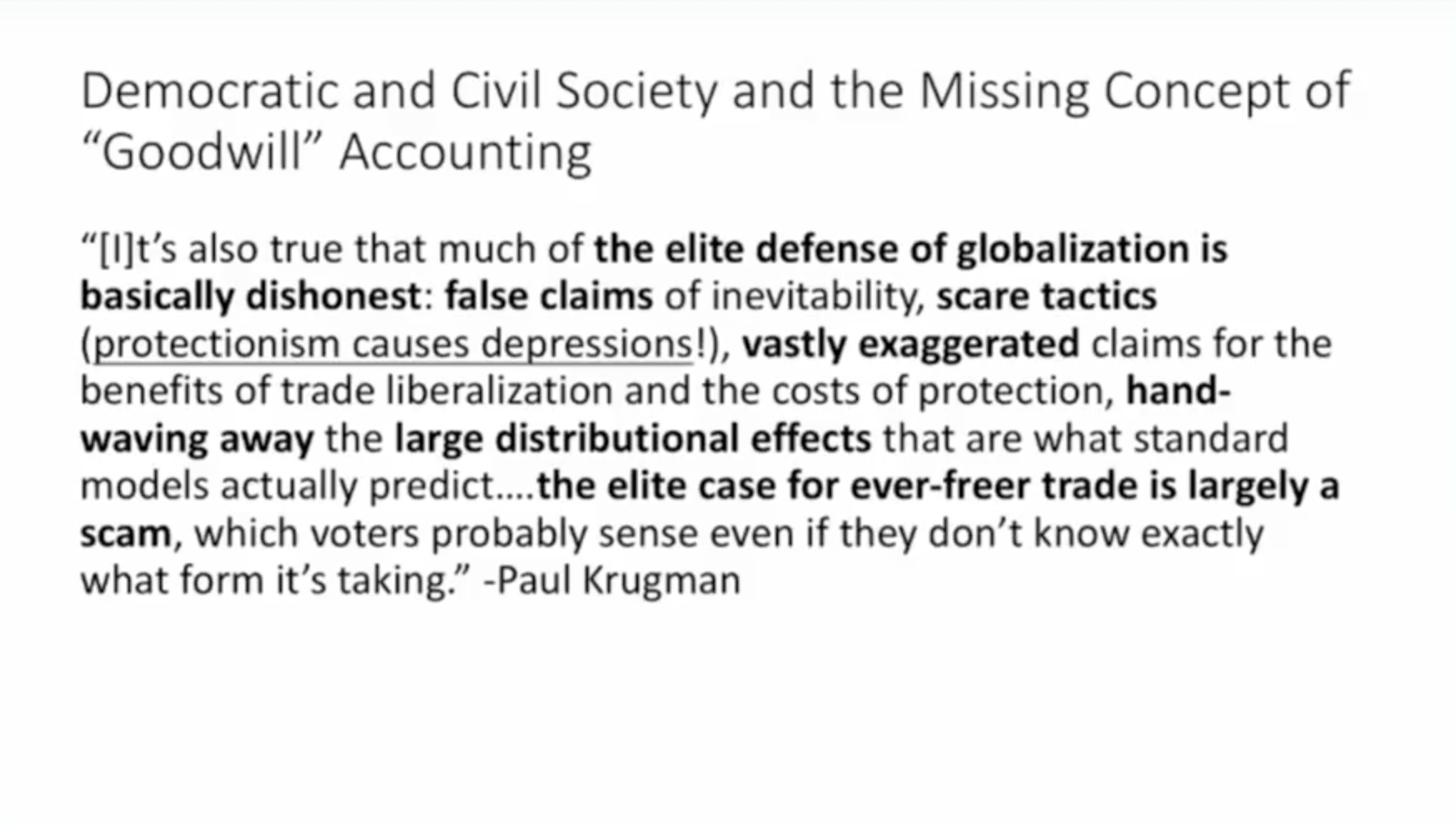

So the bigger point is economists had very good reason to anticipate that more open trade would hurt the US working classes, but they either pointed chose to ignore that or rationalized it in various ways. At worst, they’d take a short-term hit and would get a new job and might have to acquire some skills….as if that were all that easy if you are supporting a family, and/or older, and employers won’t give you credit for training in later life.

Another example of “economists should have known better” is the Lipsey-Lancaster theorem. From ECONNED:

Already, in 1956, R. G. Lipsey and Kelvin Lancaster published “The General Theory of the Second Best,” also known as the Lipsey-Lancaster theorem.

Recall that the situations that economists stipulate in theoretical models are idealized, usually highly so. Consumers are rational and have access to perfect information. There are no transaction costs. Goods of a particular type are identical. Capital moves freely across borders. Using these assumptions, or similar ones, the model is then shown to produce a global optimum. This highly abstract result is then used to argue for making the world correspond as closely to the model as possible, by lowering transaction costs (such as taxes and regulatory costs) and reducing barriers to movements of goods and capital.

But these changes will not produce the fantasy world of the model. Doing business always involves costs, such as negotiating, invoicing, and shipping. Capital never moves without restriction. Buyers and sellers are never all knowing, and products are differentiated. Despite the pretense of science, it is a logical error to assume that steps that realize any of the idealized assumptions individually move the system closer to an optimum state. The Lipsey-Lancaster theorem examines this thinking and proves it to be false.

The article shows, first in narrative form, then with the required formulas, that if all the conditions for the ideal state cannot be met, trying to meet anything less than all of them will not necessarily produce an optimum. Partial fulfillment of equilibrium conditions may be positively harmful, forcing the economy to a less desirable state than it was in before. Thus simple-minded attempts to make the world resemble hypothetical optimizing models could well make matters worse.

In general, outcomes at least as good as any “second-best” reality can result from a wide variety of different policy choices. So, while abusing rarified economic models to grope toward a unique hypothetical ideal can be harmful, many different messy policy choices can lead to improvements over any current, imperfect state. There is no one, true road to economic perfection. Trudging naively along the apparent path set forth by textbook utopians may lead followers badly astray, despite the compelling simplicity of the stories they tell.

Consider an example: one area where economists are in near universal agreement is that more open trade is ever and always a good thing; those who question this thesis are dismissed as Luddites. Since economists believe that open trade is better, it follows that they favor reducing tariffs and other barriers (note: they are willing to make some exceptions for developing economies).

Yet in the early 1990s, concern in the United States rose as more and more manufacturing jobs went overseas. Indeed, the tendency has gone ever further, as entry-level jobs in some white-collar professions like the law have now gone abroad. Indeed, in software, some experts have worried that there are so few yeoman positions left in the United States that we will wind up ceding our expertise

in computer programming to India due to the inability to train a new generation of professionals here.How did economists react? The typical responses took two forms. One was that there would be job losses, but based on the model, the effect would not be significant. The other was that since the net effect would be positive, the winners could subsidize the losers. Since mechanisms to do so (more progressive taxes to fund job retraining, assistance to move to regions with better job prospects) have not been implemented on a meaningful scale, this is cold comfort to those who were on the wrong side of this deal. And as we will see, the naive stance of the United States in trade policy against countries, like China and Japan, that pursue mercantilist policies designed to maintain trade surpluses, led to persistent U.S. trade deficits.

In other words, even though economists will often point out that the debates in advanced courses and colloquia acknowledge the problems with the models taught in undergraduate programs, that is no defense. Mainstream economics, which serves as the foundation for policy-making, is if anything more simplified than that. The fact is that the version of economics bandied about in the political sphere isn’t grounded in scholarship. It’s propaganda that’s treated with more respect than it should be because its purveyors toss out equations when challenged.

Astute, clever remark. I would add that this attitude is not very different from that of PropOrNot and the likes who depict whoever critisizes the TINA crowd as “useful idiots”. The liberal press plays the straw man fallacy so massively against those many grouped as “populists”…

it reminds me of the way luddites have been characterized by official histories.

Regarding this issues on trade I have always been puzzled that we focus the analysis mainly in the effects of trade and productivity between countries and less frequently on rural vs urban areas or touristic vs manufacturing regions, connected vs isolated regions. In the EU it is recognized that certain regions have suffered the most during economic integration and some programs have been implemented to reduce this inequality. Of course the competitive advantage crowd dislike it. I intuitively think that a wage earner, or a producer, in rural areas, regardless these are in Iowa, Salamanca or Limousin will almost certainly loose when trade is further liberalised. This is widely recognised and that’s why rural producers have ended relying in subsidies at both sides of the pond. But then we critisize those subsidies as an anti free-trade sin that harms producers in developing countries. I think these models mentioned in the article do not give a damn on regional issues.

>then we critisize those subsidies as an anti free-trade sin

Hmmm, I never made that connection – those subsidies are precisely the “winners subsidizing the losers” but The Economics Profession won’t admit it.

on farm subsidies:

here’s a cool database, searchable by county, and including everyone who obtains a check for farming/ranching.

https://farm.ewg.org/top_recips.php?fips=48319&progcode=livestock®ionname=MasonCounty,Texas

in a small place like this(pop:4500), I know, or am at least acquainted with, every one of these folks(one is the property tax ass.,at least 5 don’t live here, and none are what I would call “in dire straits”.)

observations derived from this: the folks who yell the loudest about “welfare” are at the top end of that list.

i’d say 80% of their employees are immigrants of varying status(and they also yell the loudest about the border)

the peanut and mohair subsidies went away in the late 90’s, to be replaced with cattle on the large, old family ranches…and with hunting(still below 9-11-2001 levels)…and then with wine grapes(which seems to be a “rich man’s” endeavor…and which don’t qualify for the ag exemption for some reason, and enjoy no subsidies, as yet)

out of the thousands of cows that come through the 3 stockyards/auctions in a given week, none of them are eaten here.

unemployment here(last i looked) was still around 14%, and a lot of that employment is convenience stores and waitressing and other such low-paid things. the 3 largest employers are, in order, the school, the (one) city and the county…all heavily subsidized/shored up with grants.

a handful of rich cattlemen(not a few of which are absentee and in it for the write-off) might suffer some with the “trade war”.

I wonder if any one else will even notice…

Wine grapes require an enormous capital investment, and don’t yield anything worthwhile for at least 5 years, in the meantime requiring intensive management. I’ve worked in a vineyard, pruning in the winter, just a small part of the cycle.

There can also be a big payoff, but even that isn’t sure, especially in a new wine-growing area. So, “rich man’s endeavor.” It’s a place to park money, since the payoff is so far in the future.

Yup.

I’ve been trying to put in a couple of acres for 2 years(mom sits upon the money, and has gotten scattered and cross,lol)

growing wine here was my idea(unacknowledged) from 23 years ago, when all the legacy ag was still “the way we do things”.

same with olives(at the time, one couldn’t get the more cold tolerant varieties without APHIS quarantines, etc)

Initial expenditure is my problem…getting water to the back pasture, mainly.

so now I’m collecting the pipe, incrementally, so she doesn’t notice.

The big issue beyond infrastructure is labour.

I can prolly manage the pruning in the winter for 2-3 acres,along with maybe a crew of goats(see:”tragedy”=gr.”goat song”=goats pruned in ancient times) but harvest(sans the big machine) is a daunting prospect.

there’s a sort of mini-movement out here for small growers/boutique wine that’s encouraging. There’s really no reason to favor the big boys.

so far, the regs(brand new) are conducive to both styles.

I’ve been pushing for some thought to be given to all the ancillary activities that go with a mature wine industry….grappa/cognac/brandy, vinegar, growing oak to mollify the oak gods, etc.

so far, the regs make distilling on a small scale…or even making vinegar from not-up-to-par wine, impossible.

Dear Yves Smith,

The problem is quite simple: the theory of comparative advantage is wrong. It was originally developed based on a misinterpretation of the original purpose, content and implications of David Ricardo’s famous numerical example in the Principles. This is why you won’t find any explicit or implicit reference to such a theory in Ricardo’s book.

You can find the detailed explanation for the above affirmation here: Overcoming Absolute and Comparative Advantage: A Reappraisal of the Relative Cheapness of Foreign Commodities As the Basis of International Trade

One does not have to rely on the Stolper-Samuelson theorem to realise that workers and capital owners in certain industries might indeed get hurt by foreign competitors. This recognition is already present in Smith and Ricardo. From this fact alone one cannot deduce, however, that protection is a better policy than free trade, since it is also known that protection hurts almost everybody instead of specific groups.

Thank you.

Britain had a strong incentive to discourage countries like Portugal from becoming competitors to her textile industry. Britain had no chance to compete with wine production so the whole comparative advantage thing was a nonsense to begin with. Portugal ignored Ricardo and today she has a textile industry employing 100,000. Other wine producing countries such as Italy and Germany developed textile industries that are today the world’s third and fourth largest respectively.

A clear lesson for countries that want to develop economically is to ignore what mainstream economists say about free trade, and to develop their own industries.

Britain deliberately destroyed the textile and manufacturing industries in India; that region’s cloth, gun manufacturing, and general production was the equal of anyone at the time of its conquest. A century later it had no much manufacturing and just some cottage level textiles making; it was a very valuable source of raw materials like cotton and a important market for clothing and other finish goods.

Do you have any evidence that proves that Britain tried to discourage the textile industry of Portugal? As far as I know, there were internal factors and forces which impeded the flourishment of the Portuguese textile industry.

Mainstream economists are indeed making a dismal case for free trade these days. This does not mean, though, that protection is superior to free trade. The latter in fact encourages the spread of industrials methods of production more effectively than any protectionist policy.

Firstly you have to define free trade.

Free trade can be defined as the trade policy recommendation that national governments should abstain from intervening in the voluntary exchange of commodities and services across political borders between the residents of their respective countries. Under a free-trade regime, national governments do not impose artificial barriers — such as tariffs, quotas, subsidies or non-tariff barriers — with the purpose of hampering the importation of specific commodities and services in order to secure their production within national borders.

In short, free trade can be described as a policy of non-discrimination with respect to foreign-made commodities and services.

In reply have you acquainted yourself with the view of De Soto.

I am not a fan of namedropping. Instead, I try to make up my own ideas about topics.

Sorry I did not know attribution on a pivotal aspect of academic opinion – introspection was akin to name dropping.

So I take it that all your thoughts are original.

If I may help markets are things of law as such your views are abstract and not really helpful.

Protection is undoubtedly superior when a country is trying to develop its own industries. All major economies have protected their industries in their growth stages.

I am sure that there are advantages to free trade between mature economies playing on a level playing field. There will always be winners and losers; unfortunately the losers tend to be the workers.

Correlation is not causation, as you might know. Protection has been widely used by almost every country, but this fact does not prove that it can stimulate the use of industrial methods of production or industrialisation more effectively than free trade.

Protection stimulates a specific industry at the expense of other industries.

Sorry but predominately that is not the case, financialization precedes events, see Hudson et al.

Excellent article Yves! Do you (and other NC staff) think there’s a legal case for prosecuting these economists on the grounds of false scholarship, wasted public money on their employment and tenure and the huge harm that they caused by being dishonest?

It worked in the Soviet Union, didn’t it?

“We don’t need no Kondratiev winter,” as Uncle Joe used to mutter.about the “kulak-professor.”

Is it possible that the only thing that they* might be accused of is failing to admit who their employer is?

*they being those Minsky called “court economists”

Posting a performance or completion bond, or using some other mechanism to get economist and policy maker skin into the game could help. Otherwise, they are quite literally playing with house money; yours, mine and every other disposable citizen’s.

While that approach may escape implementation, the notion of post-action review should not. Call out the miscreants for their follies, name names, insist on specifics, details, commitments and accountability. Now, how to get that on the agenda at the next meetings of the Fed, AEA, Davos et al.

But then who does the post action review? There needs to be a very serious backlash against the profession that targets their tenures and reputations. Otherwise it’s not going to stop the likes of Harvard from employing them. Look at Rogoff! The man still has tenure!! What provisions are there in the American legal system that could help with this? Class action lawsuit?

For me ‘the comparative advantage’ and ‘the optimal currency area’ are two sides of the same coin.

Btw, where are the articles about how the areas in the US with trade surplus to the rest of the dollar zone (the rest of the US) should reduce their surplus or fund the trade-deficit areas by fiscal-transfers?

They do. Look at welfare payments.

Would you say the fiscal transfers are sufficient according to the optimal currency area theory?

If not, how much more would need to be transferred?

If yes, why is the flyover country in the state it is?

Transfer payments have been systematically cut back since, about, Carter, and certainly Reagan. It’s a political issue – and the economic argument isn’t being made enough.

That said, transfer payments are a lot like petro-socialism: they don’t build an alternative economic foundation for when the good times fail – witness Venezuela. And flyover country. An industrial policy is necessary; even better would be economic democracy, facilitating worker ownership and providing worker-based enterprises with necessary capital (MMT).

ASSUMPTIONS OF COMPARATIVE ADVANTAGE

The following are the assumptions of the Ricardian doctrine of comparative advantage:

There are only two countries, assume A and B.

Both of them produce the same two commodities, X and Y.

Labour is the only factor of production.

The supply of labour is unchanged.

All labour units are homogeneous.

Tastes are similar in both countries.

The labour cost determines the price of the two commodities

The production of commodities is done under the law of constant costs or returns.

The two countries trade on the barter system.

Technological knowledge is unchanged.

Factors of production are perfectly mobile within each country. However, they are immobile between the two countries.

Free trade is undertaken between the two countries. Trade barriers and restrictions in the movement of commodities are absent.

Transport costs are not incurred in carrying trade between the two countries.

Factors of production are fully employed in both the countries.

The exchange ratio for the two commodities is the same.

As you can see, comparative advantage is a nonsense that relies on absurd assumptions that almost never hold true in the real world.

Yes, but one has to distinguish between the textbook notion of comparative advantage and what Ricardo actually wrote. The term Ricardian trade model or Ricardian theory of comparative advantage is a misnomer, as it is explained in the paper “Ricardo’s Numerical Example Versus Ricardian Trade Model: A Comparison of Two Distinct Notions of Comparative Advantage“.

Moreover, Ricardo did not make any of the assumptions you have listed.

From the title of this piece, I had hoped that the content would involve discussing how trade policy is NOT being informed by economics. I didn’t see much of that, apart from Stopher-Samuelson. How could anyone look at the model described above (clearly a toy) and be convinced that policymakers are doing free-trade negotiations because of its influence? Surely the power of economists is being vastly overrated here?

Another excellent trade article, summarizing points this blog has made for years. Particularly relevant these days is how trade works alongside financialization and automation to give capital another tool for repressing wages. Although I suspect Trump’s new tariffs will do short-term economic damage, if they make every company with a long global supply chain nervous, they could help stop wage-repressive tactics in the long run. Unless, that is, the next Democrat in office returns to the Clinton era orthodoxy. Have to keep an eye on that.

I have come to agree with this position only recently (not being very economically literate) and I have to ask why medicine is the only “profession” with malpractice codes. It seems as if we would all benefit were economics to have such a thing. I say this because it is clear to me that some (not all, but some) economics seem to be politically motivated, providing cover for any party willing to subsidize their efforts.

I think there are some valid basics, but economics, as practiced, is political ideology, not science. “Malpractice” might be beside the point. They’re doing what they’re supposed to do; it just isn’t what we want or need.

“Comparative advantage” is an idea that very few seem to grasp. In economic theory, it has the great virtue of being “robust”. What “robust” means is that pretty much regardless of what other factors or circumstances you assume, “comparative advantage” explains why people would specialize and trade. It explains why a tailor hires an accountant and vice versa.

“Comparative advantage” is simply not adequate by itself to explain the patterns of long distance trade and financial investment. If an economist is bloviating with no reference to sunk-cost investment or economic rents, he’s best ignored.

That’s interesting. You are saying, in effect, that comparative advantage explains division of labor. That may be so in some ideal world. In the real world, division of labor is often enforced without regard to any natural advantage, so perhaps it is not so “robust” after all. Otherwise one could argue that those who fulfill the most menial or disagreeable tasks for society are naturally suited for their occupations. Thus “comparative advantage” simultaneously justifies the CEOs salary in the U.S. meritocracy and the caste system in India. This is a “robust” concept indeed!

Look back at David May’s list of the “assumptions” that underly the theory. (Thanks, David.) Economists use “assumption” in a misleading way, to mean “requirements.” Without the requirements, the theory is invalid, at least as applied to trade.

Yet another “Case of the Way-Smart Model”

In another life I did air quality modeling of intersections under development pressures. I worked with traffic engineers who studied these same intersections and produced traffic studies on how to deal with the increasing volumes of traffic. You have seen the results: a new left turn lane; another right turn lane; single lane collector streets become dual lane arterials. Traffic moves nicely. Everything is hunky-dory. The model is the genius that permits complexity.

Once, under intersection conditions that produced near gridlock, I had an epiphany. While you and I (i.e. the boneheads) sit in traffic while the signal cycles again and again, the model (being way-smart) sends us happily on our way to our destination by a round-about route that you and I (the boneheads) could never have possibly foreseen. Congestion mitigated…development approved…yea!!

Economists, as you all know, are way-smart.

Ha Joon Chang, a Cambridge Univ. econ. professor, has the ultimate take-down of comparative advantage. It’s the theory that an economist’s 4 year old child should immediately join the work force as a fruit picker, day laborer, lawn mower, etc. You can always show that Brad Delong Jr. at 4 would benefit from trading his labor to an adult factory owner, and be better off than if Brad Jr. were living alone in the forest in complete autarky. That this nonsense passes as high wisdom is a very bad sign. At the end of the day, what is the point of an American economist? Trump’s Tariffs are probably America’s last shot at reversing de-industrialization.

Ha Joon Chang is really good on protectionism.

Also, if we don’t make things, people don’t learn the skills they would learn making things.

Thank you.

Ha Joon Chang’s book, Bad Samaritans, is excellent and needs to be read by all NC readers.

“offshoring and outsourcing did not lower total production cost, particularly when you factor in the risk of a more rigid production system and the lost of critical manufacturing know-how.”

Yes, I know of an instance of a high tech component manufacturing where in one instance $100k of limited and hard to produce product was scrapped because the process was moved overseas and the engineer that supported the process was laid off. A savings of ~100k in salaries and benefits. OK, a wash then, well no, not so fast. It would have taken said engineer about 6-8 hours to have found and corrected the error, lets say a day’s salary and benefits, or about $400, a savings of $99,600. That assumes said engineer does nothing useful the rest of the year.

Great post. Not being an economist, this is first I’ve read about the Stolper-Samuelson theorem and the Lipsey-Lancaster theorem. Thanks.

An important consideration is the many of these neoliberal economists are on the payroll of the very rich.

The other reason is that they never sought to help ordinary citizens. Quite the opposite. Most of these trade deals were written by lobbyists for the purposes of weakening the bargaining power of labor. They wanted to break up the unions and to devastate the middle class.

The fact that it was built on unrealistic assumptions was never a deterrent. It was always meant to be intellectual cover for class warfare.

It might be falling apart now though. The reason why is because when you give people nothing to lose, that’s when the existing order loses its legitimacy.

My experience is people will attempt to outsource to cheaper places regardless of comparative advantage. So if coders are super cheap in India, managers will try to go to India, even when it ended up costing much more.

The lure of price per hour is just too strong for them to resist. Of course now that US companies have invested billions into India training the workers (something they won’t do for American workers) the Indian programmers are pretty good overall.

I should add they spent the billions not for some great love of Indian workers, but to save face as they made such a catastrophic decision to outsource all this stuff in the first place.

But despite all the evidence to the contrary, they will carry on with the delusions to feed their families…

The big bucks are often for the things you don’t say.

I think the way we got here is more complicated that what you present.

Around the middle of the last century, it was clear that careful economics was going to lead to a “there’s an argument for (almost) every side” outcome. Certain individuals viewed this as bad: they liked the old “economics tells us X” way of thinking. Paul Romer attributes this view to George Stigler and references Craig Freedman’s Chicago Fundamentalism (which I haven’t read): https://paulromer.net/what-went-wrong-in-macro-historical-details/

The key thing to understand is that careful economic analysis generated a backlash, which took the form of the development of a field called law and economics, that in its origins was designed to make sure that the economics that legal professionals were trained in was what I would call dark-age economics, and what its proponents would call “true” economics. See Steven Teles Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement for this (although Teles does not understand the degree to which the economics being promoted is far from state of the art). They still teach something called Kaldor-Hicks efficiency in law schools, even though it was debunked as a nonsensical concept that is not useful for economic analysis decades ago. Kaldor-Hicks favors policies that “expand the pie” without any consideration of who benefits — i.e precisely the kinds of policies criticized in the post.

In short, the reason economic policy is based on b.s. economics is because there was a movement to create this situation. Anti-trust is messed up for very much the same reasons.

Economists are often bewildered as to why they are being blamed when most economists don’t do this kind of b.s. level analysis, e.g. https://mainlymacro.blogspot.com/2018/01/because-adviceof-economists-is-so.html. The problem is that for political purposes the concept of “economics” has been co-opted to mean dark-age economics, and the actual practice of rigorous economic analysis when it comes to policy has been sidelined. (Of course, it’s possible to find exceptions where careful economic analysis is used for policy, but this is far more rare than it should be given that the revolution in economic analytic methods took place about 60 years ago.)

Population , employment and income dynamics, as noted, are insightful ways to look at trends and prepare for anticipated changes. In this comment, non-seasonally adjusted estimated labor force data (ages 16 and over) from the Merged Outgoing Rotation Groups (a subset of the Current Population Survey) available at the National Bureau of Economic Research for 1979 and 2017 are used. The resulting compiled dataset was for complete data by gender and race (black only, white only) . The data are summarized in TABLE 1. If the 1979 Employment-Population (16 & over) ratios (E/P – employees per 100 population) were applied to the 2017 population, 1) the labor force would have been 2,020,037 larger and 2) those reporting full- and part-time work with income would have been 2,584,614 larger. The discrepancy is attributed to changes in those not in the labor force, those unemployed and those not at work.

TABLE 1 Labor Force and Employment Status and 2017

Projections based on 1979 Employment-Popoulation (E/P)

Ratios

1979 2017 Labor Force & Employment

102,616,126 145,044,020 Labor Force 16 & Over

147,074,057 If 1979 E-P Ratio in 2017

85,509,975 119,972,043 FT* & PT** with Income

122,556,667 If 1979 E-P Ratio in 2017

*FT – Full Time

**PT – Part-Time

Computing race-gender E/P ratios for the labor force E/P ratios for 1979 and 2017 reveals (see TABLE 2) that male ratios declined, female ratios increased at far greater rates than the decline in the overall (Total) E-P ratio. This likely reflects differential effects of industrial changes in employment, likely ones in which globalization was more likely having impact on male employment and domestic changes having impact on male employment.

TABLE 2. Race-Gender Specific Employment-Population (E/P)

Ratios of Labor Force (16 and over) by Race & Gender

Year

WM – White male

WF – White female

BM – Black male

BF – Black female

Year WM WF BM BF Total

1979 78.6 50.5 71.4 53.1 63.6

2017 69.5 56.4 64.6 60.3 62.7

The differences over time are not as pronounced for those working full-and part-time reporting weekly earnings (see TABLE 3) .

TABLE 3. Race-Gender Specific Employment-Population (E/P)

Ratios of Full- and Part-Time Employed (16 and over)

With Income by Race & Gender

Year WM WF BM BF Total

1979 63.7 43.6 59.8 44.9 53.0

2017 56.5 47.4 53.0 51.7 51.9

When gender and employment status (full-time and part-time) controls are used to calculate specific E/P ratios, there are more dramatic differences, especially for men with large declines in full-time employment (see TABLE 4).

TABLE 4. Race-Gender E-P Ratios (16 and over)

Controlling for Employment Status of Those Reporting Income.

Year WM WF BM BF Total

1979 Part-Time 6.3 12.2 6.8 10.0 9.3

2017 Part-Time 9.4 14.5 9.8 13.1 11.9

1979 Full-Time 57.3 31.4 52.9 34.8 43.7

2017 Full Time 47.1 32.9 43.2 38.6 39.9

Meanwhile, there are notable changes in income. Median income data in constant (2017) dollars is reported below (see TABLE 5) rather than mean income because the MORG data have upper limits on income reporting which in addition are different for 1979 and 2017. The largest decline in median income was experienced by the white male subcategory, reflecting the significant decline in full-time employment. Female median income increased from 1979 to 2017, boosting the overall or total median income.

TABLE 5 Median Weekly Income in

Constant (2017) Dollars for Full- and Part-Time

Workers With Income by Race and Gender.

Year WM WF BM BF Total

1979 1200 500 672 493 667

2017 900 654 654 576 760

To address changes of within category (race-gender) income distributions Gini (inequality) measures using mid-point (10, 30, 50, 70, 90) quintile income figures. TABLE 6 that the overall Gini increased from .404 to .530. And this pattern was true for all race-gender subcategories except for black males whose Gini index figures decline from .451 to .382 indicating greater within category income equality.

Year WM WF BM BF Total

1979 0.508 0.387 0.451 0.270 0.404

2017 0.522 0.412 0.382 0.350 0.530

The next exercise will be to add age-specific subcategories to add detail to demographic structures and dynamics and their relationship to the labor force and income.

Yes, because “laissez faire” does that. It isn’t as if we didn’t already know that.

“Free trade” is just another word for the same thing. In reality, markets and trade cannot be “free,” because they depend on rules and law enforcement.

I have been wondering for decades just who will buy enough to sustain manufacturers outside the States, if everyone is poor, and just what does anyone think will happen when we Americans really have nothing left to lose? A 300+ million, still well educated, armed, unhappy, desperate, impoverished nation armed with nukes, and still a good central chunk of the Earth’s economy. This could cause everyone some problems. Just saying.

Yet, TPTB all seem to like Sargent Schultz in Hogan’s Heroes: I see nothing! I hear nothing! I know nothing! And then adding But I feel fine, so everything is great!!

I think modern “economics” and political ideologies are like opium for the Elites. When someone gets uneasy about the economy or politics, someone come running with the latest Friedman piece, WSJ economic “analysis” or throws an Econ text at them and the clear darkness of unreasoned faith cleanses them of any heretical reasoning.

Hi Yves,

Excellent article. It’s very interesting that Brad DeLong has come out with his admission given that he was a Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury under Robert Rubin. I’m still waiting for Paul Krugman to qualify his cheerleading for NAFTA and China’s accession to the WTO. BTW, Can you include the link to your earlier article?

Thanks!

P

This was foreseen (by non-economists, at that) in the 80’s in the Star Wars: Next Generation series.

Note the Ferengi. (This reference is not comedic in intention.)

“The Ferengi were originally meant to replace the Klingons on Star Trek: The Next Generation as the Federation’s arch-rival,[citation needed] but viewers could not see such comical-looking creatures as posing any kind of serious threat. Thus, Paramount repurposed them as a one-dimensional nuisance, and plots involving them were usually comedic ones.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferengi

Replace the Klingons as the Federation’s arch-rival. Instead, the Ferengi took over the Federation.

Given that we know manufacturing costs are made up of Labor, Overhead, and Materials in reverse order of magnitude of cost. It is kind of difficult to blame Labor Cost as the factor in the transition from the US to China. We are talking 10% or less in the cost of manufacturing for Labor. The difference in Labor cost is not great enough to shift manufacturing as you still have to pay for transportation and the cost of inventory by ocean, the stay in customs, and then land transportation. Gettelfinger in front of Congress made the same claim on the Labor cost going into a vehicle. He was right.

So that leaves Overhead and Materials. Materials will be approximately the same.

Here is an example of what actual Overhead in China would involve:

“Stopping between the cornfields and the primary school playground, the workers dumped buckets of bubbling white liquid onto the ground. Then they turned around and drove right back through the gates of their factory compound without a word. In March 2008 Li and other farmers in Gaolong, a village in the central plains of Henan Province near the Yellow River, told a Washington Post reporter that workers from the nearby Luoyang Zhonggui High-Technology Co. had been dumping this industrial waste in fields around their village every day for nine months. The liquid, silicon tetrachloride, was the byproduct of polysilicon production and it is a highly toxic substance. When exposed to humid air, silicone tetrachloride turns into acids and poisonous hydrogen chloride gas, which can make people dizzy and cause breathing difficulties. Ren Bingyan, a professor of Material Sciences at Hebei Industrial University, contacted by the Post, told the paper that ‘the land where you dump or bury it will be infertile. No grass or trees will grow in its place … It is … poisonous, it is polluting. Human beings can never touch it.’ When the dumping began, crops wilted from the white dust which sometimes rose in clouds several feet off the ground and spread over the fields as the liquid dried. Village farmers began to faint and became ill. And at night, villagers said ‘the factory’s chimneys released a loud whoosh of acrid air that stung their eyes and made it hard to breath.’ It’s poison air.’”

I have been in Shanghai on the worse air pollution day ever. Tianjin and Beijing suffer from similar quality of air. I could talk about Manila, Bangkok, Pitsanlok, Jakarta, and other places as well. The Overhead in these countries is far less than in the US or Europe for that matter. t is in Overhead the biggest difference lies.

Yes, as has been noted here before, the real incentive is not merely reducing labor costs so much as regulatory arbitrage that relaxes environmental as well as labor regulations

Comparative advantage is an equilibrium model – that should be enough said except 3 centuries of economist fail to distinguish between steady state and dynamic systems. They’d tell us a swing is a chair.

Brad Delong thinks that hysteresis is a problem to work around. That’s clever like trying to work around the problem that humans have functioning brains.

Economics is the study of corpses.

As currently practiced, yes, or like the old theological arguments in over how many angels could fit on a head of a pin. Fake studies. Economics as it use to be studied, and taught, and as modern political economy still is, was not. Adam Smith, John Mills, Karl Marx, and even John Rawls would have been considered part of economic studies. Current mainstream economic studies are stripped out, overly simplified, and distorted, remains of what use to be and fits the desired views of current elites.