Yves here. This study on the long-term effects of the Roman road network is clever and has some factoids (abandonment of the wheel!) that were new to me.

By Carl-Johan Dalgaard, Professor, Department of Economics, University of Copenhagen, Nicolai Kaarsen, Economist, Danish Economic Councils, Ola Olsson, Professor of Economics at University of Gothenburg, and Pablo Selaya, Associate Professor of Development Economics, University of Copenhagen. Originally published at VoxEU

Although spatial differences in economic development tend to be highly persistent over time, this is not always the case. This column combines novel data on Roman Empire road networks with data on night-time light intensity to explore the persistence and non-persistence of a key proximate source of growth – public goods provision. Several empirical strategies all point to the Roman road network as playing an important role in the persistence of subsequent development.

Spatial differences in economic development tend to be highly persistent over time. Comin et al. (2010) document, for example, that countries that were closer to the technological frontier as early as 1500 CE are comparatively richer and more technologically sophisticated today, while Maloney and Valencia (2016) document persistence in population density across half a millennium, comparing regions at the sub-national level within the New World. Findings such as these have led to a large literature that tries to identify fundamental sources of comparative development in initial conditions, and historical processes from the distant past. Spolaore and Wacziarg (2013), Nunn (2014), and Ashraf and Galor (2018) present recent surveys. At the same time, differences in comparative development are not always persistent. For example, Acemoglu et al. (2002) document a reversal of fortune across former colonies during the last 500 years.

These findings raise questions about which proximate factors generate the observed persistence in comparative development, and why the persistence sometimes breaks down. In this regard, we know much less. A deeper understanding of the channels through which persistence in comparative development emerges may leave clues about which fundamentals are important, and how to support development in situations where these fundamentals are lacking.

In a recent study, we explore the persistence and non-persistence of a key proximate source of growth – public goods provision (Dalgaard et al. 2018). The specific form of public good in focus is roads, and we take the roads built during the Roman Empire as our point of departure. In particular, we examine the persistence in road density across time, and its role in generating persistence in economic development across regions that were part of the Roman Empire at the beginning of the 2nd century.

The Data

Throughout the analysis, our unit of observation is a pixel of 1×1 degrees of latitude by longitude. In order to measure road density, we build a buffer of 5 km on each side of all roads and measure the buffer area relative to the total pixel area. The data on Roman roads derive from Talbert (2000). We repeat that exercise for the network of modern main roads, with data from the Seamless Digital Chart of the World Base Map (v. 3.01).

We measure economic activity during antiquity using the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire by Åhlfeldt (2017), which provides data on Roman settlements circa 500 CE. For the contemporary era, we use two independent measures of economic activity: population density and the intensity of lights at night, following Henderson et al. (2012).

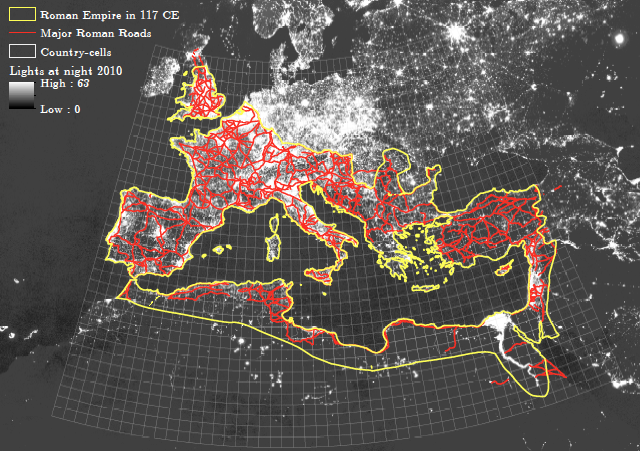

Figure 1 Major roads of the Roman Empire

Notes: The map shows major Roman roads (red lines) within the boundaries of the Roman Empire (yellow lines) in 117 CE, and nightlights intensity in 2010 in the background (white color).

Figure 1 gives a visual impression of the road network within the Roman Empire in 117 CE. At its zenith, the system involved an impressive 80,000km of roads. The map also shows contemporary economic activity measured by nightlights. From a bird’s-eye view, there does seem to be a (reduced-form) link between the location of ancient roads, and economic activity today. To understand that link better, we turn to regression analysis.

Empirical Approach and Baseline Findings

A key challenge in identifying the effects of ancient infrastructure is filtering out the effect of underlying (geographic) factors that may have influenced both Roman road density and modern-day outcomes. Another concern is how to separate the effect of ancient infrastructure on economic development from the potential broader influence of the Empire (e.g. via institutional or cultural channels).

We address these issues in several ways. First, we focus exclusively on observations (i) within the boundaries of the Roman Empire, and (ii) that were ‘treated’ by at least one road. By focusing on areas connected to the network, we reduce the risk of omitted variables bias, and the risk that our results convolute the impact from the legacy of Roman rule more broadly (e.g. Landes 1998). To further partial out a potential Roman legacy on contemporary outcomes, we control for country fixed effects as well as language fixed effects, which help us to deal with institutional and within-country cultural variation (e.g. Andersen et al. 2016). Second, based on the literature on Roman road construction and our own formal tests thereof, we control extensively for potential geographic confounders throughout the entire analysis. Third, we exploit a natural experiment to which we return below.

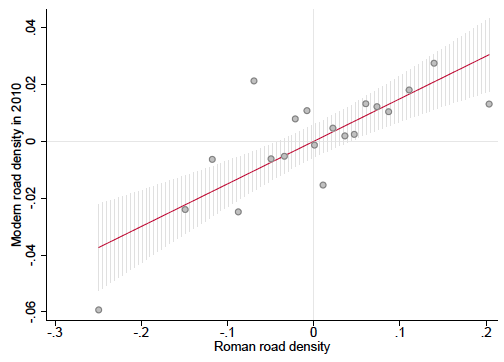

Our baseline findings indicate a clear tendency for persistence in road density within the areas covered by the empire by 117 CE. Figure 2 illustrates this result – areas that featured relatively high road density in antiquity on average also feature relatively high road density today.

Figure 2 Modern and Roman road density

Notes: The figure shows the conditional residual binned scatter plot of the relationship between Modern road density (in logs) and Roman road density (in logs) within the Roman Empire in 117 CE. The binned scatter plot groups the x-axis variable into equal-sized bins, computes the mean of the x-axis and y-axis variables within each bin, and shows a scatterplot of these data points. Also imposed is a 95% CI.

The footmarks of Roman roads are visible elsewhere. By the end of antiquity, areas with greater density of Roman roads featured greater settlement density, and for the contemporary era we also find greater population density as well as greater nightlights density. These findings suggest that, on average, early infrastructure investments tended to persist over time, and attracted – or possibly generated – economic activity. Overall, our baseline results indicate that public goods provision likely plays an important role in generating persistence in comparative development.

Persistence and Non-Persistence in Roads and Comparative Development

Despite our best efforts, our baseline findings may still suffer from omitted variable bias. To gauge the likelihood that this is the case, we turn to a third identification strategy, namely, using the abandonment of the wheel as a natural experiment.

A remarkable fact of world history is that wheeled transport disappeared in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) during the second half of the first millennium CE – which is perhaps especially surprising in that wheeled transport had a very long history in that region before its abandonment.

Bulliet (1990 [1975]) argues that the key proximate reason for the abandonment of wheeled carriages in MENA was the emergence of the camel caravan (“the ship of the desert”) as a more cost-effective mode of transporting goods. While this seems like a reasonable explanation, it immediately prompts the question of why the ox-drawn carriage then continued to dominate land-based transport until the first half of the first millennium CE. After all, the domestication of the camel on the Arabian Peninsula pre-dates the Roman era by millennia. Bulliet’s core argument is that a series of developments had to take place before the camel could emerge as the dominant mode of inland transport in MENA. In particular, the emergence of a new type of camel saddle by 100 BCE made it possible for camel herding tribesmen to utilise new types of effective weapons, which allowed them to gradually gain control of the trade routes and, therefore, gain political power as well. Accordingly, the camel caravan could not enter the scene in a major way until these events had unfolded.

From the point of view of the present study, the abandonment of the wheel experiment in MENA opens the door to an interesting set of tests. Naturally, within a region where wheeled transport disappears, one would expect to see less maintenance of (Roman) roads. Moreover, when wheeled vehicles reappear in the late modern period, the principles underlying road construction surely differed from those during Roman times. Consequently, in the MENA region, Roman roads should be a weak predictor of contemporary roads density and, by extension, Roman roads should also be a weak predictor of contemporary comparative development. In contrast, within the European region where wheeled carriages were in use throughout the period, one would expect more maintenance and therefore more persistence in road density and, by extension, Roman roads should be a stronger predictor of contemporaneous comparative development.

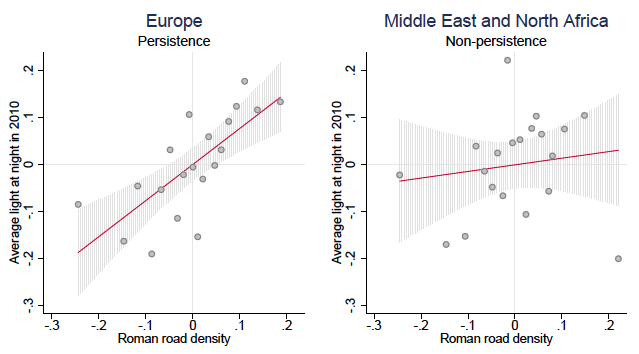

When we split the data and estimate our baseline model on the MENA and the European samples separately, this differentiated influence from Roman roads indeed emerges. Roman road density is not a statistically strong predictor of current road density nor economic activity within MENA, despite the fact that Roman roads do predict comparative economic activity prior to the abandonment of the wheel. Within the European region, Roman roads not only predict current infrastructure, but also ancient and current economic activity.

Figure 3 provides a visual illustration of the differentiated link between Roman roads and comparative development within MENA and Europe, respectively.

Figure 3 Nightlight intensity and Roman road density

Notes: The figure shows the conditional residual binned scatter plot of the relationship between nightlight intensity (in logs) in 2010 and Roman road density (in logs) within the European and MENA regions of the Roman Empire in 117 CE. The binned scatter plots group the x-axis variable into equal-sized bins, compute the mean of the x-axis and y-axis variables within each bin, and show a scatterplot of these data points. Also illustrated is a 95% CI.

Conclusion

In some ways, the emergence of the Roman road network is almost a natural experiment – in light of the military purpose of the roads, the preferred straightness of their construction, and their construction in newly conquered and often undeveloped regions. This type of public good seems to have had a persistent influence on subsequent public good allocations and comparative development. At the same time, the abandonment of the wheel shock in MENA appears to have been powerful enough to cause that degree of persistence to break down. Overall, our analysis suggests that public good provision is a powerful channel through which persistence in comparative development comes about.

See original post for references

An interesting analysis. Perhaps.

But couldn’t it also be possible that the Ancient Romans built roads in the most naturally advantageous locations for future development? The Romans were not, after all, a stupid people. Maybe these locations simply offer advantages in terms of grade, locations relative to rivers, natural obstacles, etc., and those factors still rule.

I mean, even today, most big cities are located on harbors or navigable rivers. The good location came before the development of the cities, not the other way around.

The Roman roads certainly don’t account for the real bright spot on the light map: Germany.

The Romans would have built roads there too but the Germans gave them the boot. My guess is there were probably still roads in the area at the time, just not ones the Romans controlled.

In the first century of the Roman Empire, the German region was far, far behind Rome in technology, social organization, and population density. Yes, they did have the big win in Teutonburg[sp?} Forest, but the leaders for the German side in that battle were hunted down and eliminated within a few years.

Rome stayed out of what is now Germany not because they couldn’t have conquered it. Their extensive raids every generation or so showed that they could have. They stayed out because there wasn’t enough they to plunder or seize control of that could pay for the costs of the conquest and domination.

The relationship of the German region with the Roman Empire was like that of the hill tribes of Southeast Asia with the lowland slave states such as Thailand, Burma, and Cambodia.

During the course of the Roman Empire, the German region developed and closed the gap with Rome. Something like China over the past decades only at about 1/10 the speed.

One can see a process of diffusion of material and cultural technology from the Mediterranean coast into the Celtic regions (which were developed enough to pay for their conquest, thus Gaul and Britain), then the German regions, then the Slavic regions.

Many of their roads were built over nasty conditions. Materials were expensive and difficult to move, so they would often go in relatively straight lines to cut down on total materials needed as well as making travel faster. Railroads in the 1800s and early 1900s were built similarly to Roman roads.

Here is an example of them building a road using wood fascines over peat bogs in Yorkshire that survived 2,000 years until they ran into problems with modern heavy vehicles. The amusing part was they reconstructed sections using the exact same techniques the Romans used after trying more modern techniques (osier beds are plantings of a type of willow, Salix viminalis, that is often used for basket weaving etc).: https://books.google.com/books?id=dc_8gu02ycwC&pg=PA196&lpg=PA196&dq=yorkshire+roman+road+fascine&source=bl&ots=d_cwQKSSfd&sig=X62A2pA80Hvt0FEZSOJDdFBbMro&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiVyIrR_q_aAhUDkVQKHVk3C4wQ6AEIXTAK#v=onepage&q=yorkshire%20roman%20road%20fascine&f=false

They do say they adjusted their analysis to take account of this, but aren’t very clear on exactly how they did it.

While sometimes roads over history do follow logical routes for obvious physical geography reasons, it is striking that different waves of road building can provide very different patterns. Often toll roads in particular (such as 18th Century turnpikes) often took very different routes specifically to ensure people kept to the ‘official’ route.

And where roads were most useful then in connecting pop centers would logically be where you would most want a road today given the raison d’etre of the pop centers remain the same.

The Roman map is interesting.

Economic development was always at best a secondary consideration when it came to planning and building Roman roads. Starting with the Via Appia in southern Italy during late 4th century BC the primary concern was always strategic, moving the legions quickly to where they would be most needed.

You think “where the legions would be most needed” was unconnected to the economics of the empire? I mean, for any individual action that might be so, but at scale and over time, the two are surely highly correlated.

Rome wasn’t based on taxation. It was based on conquest and expropriation. And what was valuable then (slaves, agricultural produce you could transport like grains, spices) bears not that much resemblance to what would be valuable today.

I said nothing about taxation, merely “economics”, broadly defined. Most of history’s empires had economies based to a significant extent on colonization (whether the conquest was ‘hard’ or ‘soft varies) and resource/labor exploitation, in effect, looting of one form or another. Whether it was the Roman legions moving on Roman roads or the British Royal Navy keeping the high seas safe for the looters of the British East India Company, the military’s role has ever been intimately tied to the economics. The more brutal the economic exploitation, the more ruthless the militarism used to perpetuate and expand it.

Your point about the long-term durability of specific chattels and economic goods is of course true, but again, I said nothing about that, merely commented on the Roman legions and the economy of the associated time.

They based it on taxes as well, and more and more so as time progressed.

During the early expansion in the republican period the infamous Publicani stood for tax collections (where the senate auctioned off the provincial tax farming to the highest bidders). After the establishment of the Principate under Augustus more formalised wealth and income taxes were instituted. And as the empire expanded to its practical limits, and the flow of new slaves, produce, silver, gold and land for distribution was reduced, taxes and other levies became more prominent as a source of funding.

There was also a less formalised obligation for prominent, wealthy citizens to sponsor or fund public building works, be it theatres, temples, assembly buildings etc., as well as public feasts and entertainments.

Their analysis of the Middle Eastern roads effectively debunks your point. The roads were presumably built on the same philosophy there, but they proved not to correlate much with later development.

Ummm – there were darn few Roman roads in MENA, as the map shows, until you get to Morocco , then and still an important source of olive oil – wild forests there consist of olives.

Not at all an ideal test case.

Fascinating article that leads to expansion of the old reading list. The Roman road persistence and impact may have some rough analog in other parts of the world.

Here are two items somewhat in keeping with the topic: The Millau Viaduct in southern France for some amazing engineering (the Romans would probably have loved it), and a fun website guaranteed to engage the inquisitive, Map Porn.

[F]un website guaranteed to engage the inquisitive, Map Porn.

Don’t know whether to praise or damn you, EM. I went to the site, and I am now unable to concentrate on anything else.

Fascinating study – studying human geography consistently shows how persistent patterns of development can be, long after the original reason behind a settlement has gone. The waterways of Europe are still dotted with old trading towns, a century or more after their raison d’etre was supplanted by the roads and railways. Ancient military towns, such as French Bastides are still populated, and if not thriving, are still bustling places 800 years after the wars that led to their construction stopped. The key point seems to have been continuous settlement – once abandoned, even great cities like Angor Wat or the numerous metropolises of pre-Columbian South America often never recover.

But there can also be negative effects. There is plenty of evidence that railroads sucked away wealth from resource based economies such as Argentina or Ireland – when they were built for moving cattle to beef hungry cities they also allowed the penetration of manufactured goods, preventing weaker regions from developing local industries or crafts. In both countries, the rail networks have little relationship to population patterns (unless you are looking at populations of cows). 1950’s and 1960’s highway networks unintentionally altered travel patterns which undermined mid sized towns, turning them from commercial/retail centres to little more than commuter dormitories.

Did the Romans first build roads, then build settlements to take adavantage of whatever useful the strategic element or natural resources that were in the area, or did the Romans first locate some useful resource or strategic elements in the area, then build roads so that they could take adavantage of them? Converesly, what happens to the road network when the local settlement loses the natural resources necessary to sustain the settlement or the purpose of the settlement?

Both. And that isn’t snark. At the center of the map, look for a perfectly straight line. That is the Via Emilia, and a number of towns arose along its length, notably Bologna, Parma, and Modena. The road more or less preexists these towns. (Not so strictly, as Bologna was probably founded by the Etruscans.) The region of Emilia-Romagna is stilll dominated by this road.

Yet the northern end of the Via Emilia is a kind of swirl, as the road system bumps up and then crosses the Alps. You have a couple of ancient cities here, Turin and Milan, both of which are created partially by their waterways and then the road network. Both cities are nearly as old as Rome itself, and Turin is one of the first cities below the Alps where it is possible to cross the Dora and the Po as well as navigate on the Dora and the Po. Add in some roads and you have a major city.

It occurred to me that the decline in wheeled traffic in the Middle East and North Africa between 500 and 1000 CE may have had to do with the conversion of those regions to Islam. The Arabs would have brought the camel, but the camel can’t be the only factor. Further, the Islamic world was connected by a highly developed network of ships. Who is our local expert in the history of North Africa?

Maybe the entire cultural gap and religious line is an ecological function of camels? Roman plus camel equals islam, roman without equals christianity? And all the deep thoughts and high culture are just epiphenomena?

I believe there is a truism where ‘history is 90% geography and 10% common sense. One of Rome’s greatest achievements was not it’s military might, but its absorption of multiple peoples and cultures of the Mediterranean into its sphere. Over time Almost the whole of the Mediterranean lands considered themselves Roman. Not only did they absorb the identities of three populations that existed before, but they also absorbed the trade/land trade routes as well. Even at the height of their power theyre military might was in their army as they were not much of a sea faring nation. Roman engineering improved upon the roads that were in all likelihood already there.

As for the Middle East/North Africa you must deal with the geography of the Sahara and adjacent Arabian deserts. Shifting sands and spring mud are not ideal grounds for either permanent roads large infantry armies or wheeled transport. This is one of the reasons the horse mounted Bedouin Arab raiders had such success in defeating the Eastern Romans and conquering Mesopotamia and the Levante.

I’d argue geography and the transition from coal to oil has more to do with the current state of affairs and circumstances of Europe compared to the MENA region than just Roman roads.

Maybe.

Or maybe a different population distribution would have changed the resource distribution.

Norway, Venezuela, the US and SA all have oil but transitioned very differently, some temporal, some spatial and some contingent.

Homo Economicus thinking penetrates everywhere:

A deeper understanding of the channels through which persistence in comparative development emerges may leave clues about which fundamentals are important, and how to support development in situations where these fundamentals are lacking.

And then a little later, of course, in comes the notion of “growth” as a public good, along with the notion, assumption really, that Roman roads with their military purpose (and paid for just how, again?) were “public goods.” I guess there are definitions that would apply. And the data are “useful” in figuring out, if one is a developer, what “public goods” paid for by others ought to be encouraged, so growth and development can continue, because both are ineluctably good, and apparently inevitable, until the asymptote is reached…

Allow me to provide the obligatory Monty Python reference:

Thanks for this post. It gives rise to many interesting thoughts about current world developments.

OK, I will put my two denaries in. I am going to say that there is a missing factor on the determination on just where those roads went and that is the subject of water. If you want to see an example of this at work, take a look at that satellite map and let your eyes wonder down to where Egypt is. You will see a thick cord of light and that is because the cities and towns are hugging the Nile river where nearly all the water is. Life may find a way but it is usually where the water is.

Back in Europe, when the Romans were planning a new town or settlement, question number one was just where the water was going to come from to make that town possible. I believe that they also calculated the maximum size of any towns by the amount of water available. If not enough was within reach, they would use huge engineering projects to bring in water from further afield. I once walked atop the Pont du Gard in southern France (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pont_du_Gard) which was designed to bring water to Nimes. It is a massive piece of sophisticate engineering but its purpose was to transport water. If they had not built it, then Nimes may have only ever been a village.

The point is that water availability decided the placing of towns which decided which way that the roads went. If the settlements persisted and thrived it may have been because the water was still there even if the Romans were not. When industrialization was getting underway, water was needed even more and if a town or city had a ready supply of water, it would be favoured. Don’t forget that Roman infrastructure persisted too and I have not only walked Roman roads but crossed Roman bridges in modern cities still in use. So when you have a water supply, roads and bridges you will always have a head start on your neighbours in terms of development.

You mean the Game of Thrones “fabulous citadel-city high on windswept hill with no visible source of water” thing doesn’t work in practice? Next thing you’ll be telling us that fire-breathing dragons carrying naked hotties are ahistoric fantasy tropes, too!

Personally I couldn’t even see where the city of Minas Tirith in “The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King” got its water from much less an economy that had enough superfluous resources to support such a large warrior-horsemen class. And as for those fire-breathing dragons that you mentioned, nothing that a heat-seeking, shoulder-launched manpad couldn’t take care of. The naked hottie would just be collateral damage unless she jumped.

The only source of water for Minas Tirith I can think of is perhaps meltwater from the mountains.

Any water supply from the Anduin would have been quickly identified and destroyed by the Mordor invaders. Gondor was attacked several times during the Third Age.

One of the most beautiful examples of ancient Roman infrastructure still in use.

Ponte Romano Verona

The lesson may very well be that investments in infrastructure, when they are spent correctly may pay for themselves many times over.

I wonder about the direction the US is going today.

– The rest of the Western world, and among the East Asian nations, China especially, have invested very heavily in the development of high speed rail. The state of American passenger rail (although the US is the leader in freight rail), is not in a good shape at all.

– The US is falling behind on other areas like Internet access. Rent seekers like Comcast must be blamed. The big issue is that there are likely consequences to underinvestment.

– It seems the US is struggling to provide the basics, as the lead water scandal of Flint shows. There are no doubt plenty more where that came from.

Overall it’s a good argument for favoring public goods over private property. It’s also a good argument against the neoliberal push to privatize all public services provided by government.

Why were there no Roman roads shown in Greece? Seems very strange.

Also, I wasn’t at all clear to me that they disproved the common-cause objection: that is, that the Romans built their roads where there was a resource base and economic activity to justify them. For instance, they built very little in the Sahara – except to a couple of famous oases. The resource base would be quite persistent, other than a few mines.

Greece is full of mountains, and presents very difficult road terrain for building and maintaining good paved roads. And the economically important areas of Greece were much more easily accessible by sea, and had well developed ports. But the Via Egnatia in the north, connecting Dyrrachium (of Civil War fame) with Byzantium was one of the more important roads in the Roman world.

Interesting, but I am not sure I buy it despite being interested in all things to do with Roman civil engineering. As jsn points out, Germany looks like quite an aberration. So does the home country of the researchers – Denmark – which the Romans never got to, but has road infrastructure slightly less dense than Germany today and has higher GDP per capita. Also, the map (but scale may not be detailed enough) shows what looks like similar density in Southern and Northern Italy (here I did not find any modern-day stats right away), while the economic difference between the two parts of Italy are obvious.

For a theory about the two parts of Italy:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w14278

A lot of it involves social capital and whether a town had a bishop in AD 1000. Their theory is that towns in southern Italy had the powerful Norse kingdom to protect them while northern towns had to roll their own defenses and developed the requisite councils and social organization to do so.

For an interesting take on this, consider a fantasy map generator:

https://mewo2.com/notes/terrain/

The idea is to generate maps that look like the maps in The Lord of the Rings and just about every fantasy novel produced since then. The approach is to generate the terrain and erode it with rivers flowing downhill and then place the cities based on water flow and distance to other cities. The cities then determine the borders. It’s kind of clever. You can imagine adding a step to produce a road system based on connecting cities that do not have good water connections.

My thought is that geography influences where people settle. There are issues of hydrology, defense, resources, transportation and the locations of other settlements. I’m guessing that most Roman roads followed older roads, but the Romans would also build roads that went straight from point A to point B even when traditional roads might have hugged the mountains or crossed the river at a ford. Settlements would then follow the road, and once the road bed was built it made sense to maintain it rather than build an alternate road.