By Shivali Pandya, a research intern at Bruegel, and Simone Tagliapietra, a Research Fellow at Bruegel, Adjunct Professor of Global Energy at the Johns Hopkins University SAIS Europe and Senior Researcher at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. Originally published at Bruegel

The EU is currently working on a new framework for screening foreign direct investments (FDI). Maritime ports represent the cornerstone of the EU trade infrastructure, as 70% of goods crossing European borders travel by sea. This blog post seeks to inform this debate by looking at recent Chinese involvement in EU ports.

In September 2017 Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, proposed a new EU framework for screening foreign direct investments (FDI), arguing that ‘if a foreign, state-owned, company wants to purchase a European harbour, part of our energy infrastructure or a defence technology firm, this should only happen in transparency, with scrutiny and debate’.

This proposal sparked a large debate in Europe over whether the EU should have the power to vet FDI and how this would work in practice.

Earlier this year, European leaders called on the Council and the European Parliament to make further progress on this topic. The Council accordingly agreed on June 13th 2018 to start negotiations with the European Parliament, in the hope of reaching an agreement before the next elections.

In light of these events, we seek to inform this debate by looking at the figures of China’s involvement in EU maritime ports.

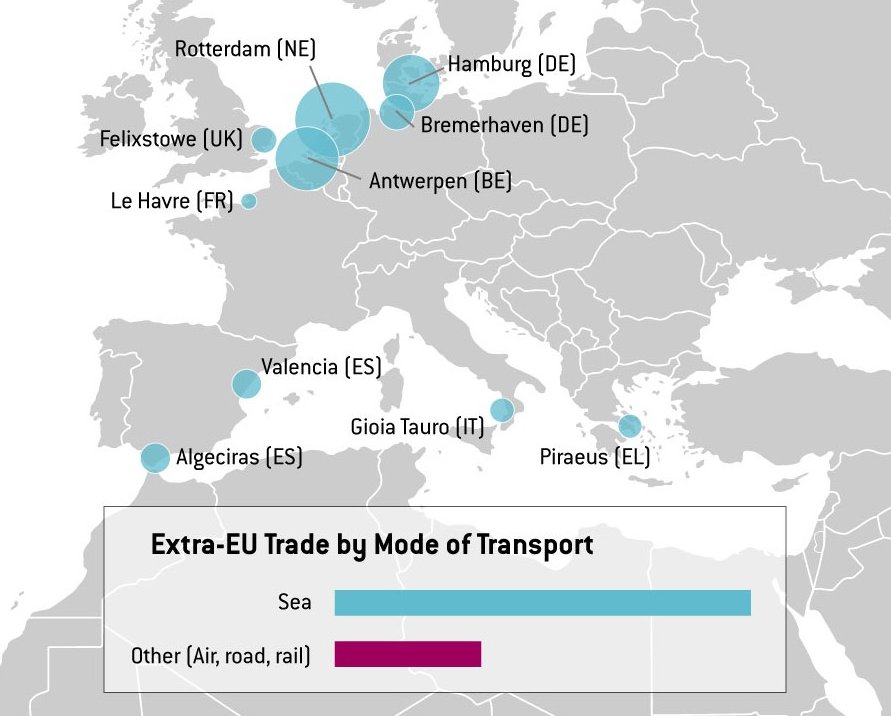

Maritime ports are a vital asset for the competitiveness of the European economy. With over 70% of goods crossing European borders travelling by sea, ports are indeed the gateway to the EU. European ports employ 1.5 million people and currently handle €1,700 billion-worth of goods (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Top ten European ports by container volume, 2016

Source: Bruegel.

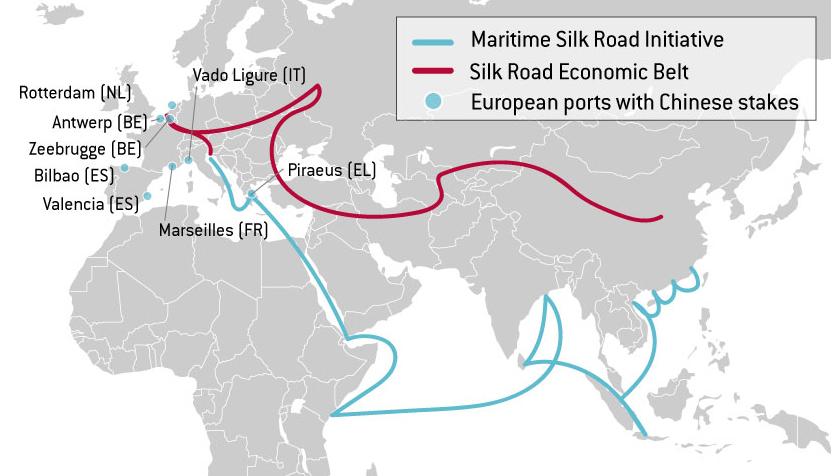

EU ports have recently caught the attention of various Chinese corporations, as China undertakes infrastructure projects around the world as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The BRI is an international infrastructure and trade development project led by the Chinese government in an effort to pursue greater cooperation and deeper integration of China into the world economy. It is, in the simplest sense, a vision to carry on the ‘Silk Road spirit’ – “communication and cooperation between the East and the West”.

The “Belt” includes overland transportation routes spanning Eurasia that connect China, Europe, Russia, and the Middle East. The “Road” refers to maritime routes starting in China that go on to Sri Lanka, Pakistan, the Middle East, eastern African states and eventually end in the Mediterranean Sea and northern European countries.

In 2016, the China Development Bank provided $12.6 billion in funding to BRI projects. China also set up the Silk Road Fund solely to invest in BRI ventures.

In this context, over the last decade, private and state-owned Chinese firms have acquired stakes in eight maritime ports in Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – The Belt and Road Initiative and Chinese stakes in top European ports

Source: Bruegel.

As the only multi-billion dollar port investment in the EU, the acquisition of a 35-year lease of Greece’s Piraeus Port by the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), certainly represents China’s flagship project in this field.

In 2008, COSCO signed a deal with the Piraeus Port Authority to operate two of the port’s three terminals. In subsequent deals COSCO has since become a majority stakeholder in the Piraeus Port Authority, which operates the port’s third terminal.

Since its acquisition by COSCO, the port has experienced unprecedented growth due to new technology and infrastructure upgrades. In six years, port traffic grew by over 300%. Under new management and with millions of euros spent to expand port capacity, COSCO aims to have Piraeus rank as one of the busiest ports in Europe.

This major investment reflects the fact that China considers the southern and eastern European regions as strategic. The Piraeus investment indeed extends beyond the maritime port itself, as China also plans to build the Land-Sea Express Route – a network of railroad connections from the port to the western Balkans and northern Europe.

In 2013 the Piraeus port was connected to the Greek railway system, but the current railway connections in the region have fewer tracts, low travel speeds, and cannot accommodate larger trains. China’s project to establish new railway lines connecting the Piraeus with the western Balkans and northern Europe could revolutionise EU trade routes. Compared to existing shipping routes, which go around the Strait of Gibraltar, the Land-Sea Express Route could indeed decrease shipping time between China and the EU by 8-12 days.

These plans to increase rail connectivity have already attracted large companies to the Piraeus. Hewlett Packard (HP), Hyundai, and Sony have all decided to open logistics centres in the Piraeus and use the port as their primary distribution centre for shipments to eastern and central Europe, as well as to northern Africa.

HP’s decision to shift operations from the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands to the Piraeus indicates that, with expanded rail and freight connections, Piraeus could represent a cheaper and more viable option compared to northern European ports.

Though the port of Rotterdam will likely maintain its primacy as the busiest port in Europe, the Piraeus port is set to continue to see an uptick in business upon the completion of more BRI projects.

Hungary, Serbia, and China already signed a trilateral plan to build a new railway line between Budapest and Belgrade, financed with loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. Construction has already begun in Serbia but remains stalled in Hungary due to an investigation by the European Commission, since Hungary did not open the project up to public tender until recently.

New cargo routes will require new storage and shipment centres and will bring more business to south-eastern Europe. The Land-Sea Express Route, in conjunction with other BRI projects, is thus set to enhance the role of southern and eastern European countries in the continental trade routes.

Notwithstanding these major developments, the EU remains divided over its response to the BRI. To date, only 11 EU Member States have officially joined the BRI project. Though most recognise the increasingly important political and economic relationship between the EU and China, there are still reservations over China’s motives behind the BRI and the impact it would have on domestic markets.

For instance, despite stating his support for increased EU-China cooperation, France’s president Emmanuel Macron expressed his hesitations by stating that the new “roads cannot be those of a new hegemony” and “cannot be one-way”. Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel has taken a similar stance, pushing for reciprocity and stating her worry that economic relations will be linked with political questions.

Unlike France and Germany, Greece has warmly welcomed Chinese investment, with its prime minister Alexis Tsipras affirming Greece’s desire to “serve as China’s gateway into Europe.” In 2017 Greece blocked an EU statement on Chinese human-rights violations, further feeding into the fear that the BRI could be used by China to exercise political leverage over involved countries.

China maintains close ties in its 16+1 framework of cooperation with 16 central and eastern European countries, all of which are either EU Member States or official EU candidate countries. The 16+1 setup has been perceived by several EU leaders as a Chinese effort to undermine EU unity.

Maritime activities are already an important component of China’s economy, and the country seeks to expand its international naval presence and operations by creating partnerships with ports in which it has stakes. China also aims to ensure access to critical infrastructure and resources it will need to drive economic growth.

Given their strategic relevance, we consider that the Council and the European Parliament cannot avoid taking maritime activities into consideration during their discussions on the EU framework for screening foreign direct investments.

business is always any nation’s or alliance’s achilles heel. blind with greed, with few or no other concerns than amassing and acquiring, businesses sell out every time. china is making itself indispensable on one continent after another.

the well deserved irony here is that greece, kicked to the curb by the EU, its supposedly natural allies, has every reason to regain some financial health by these deals, and little reason to care what the rest of the “union” thinks, fears or wants.

Varoufakis, the ex-Greek finance minister states in his book that China was warned off from making investments during the Greek debt crisis that could have helped support the Greek government against the Troika. The Greeks have no reason to see the EU as their “friends”.

If the EU is seen not as Greeks’ friends, is Greece asking to be seen by the EU as an enemy?

Is it belligerent to ask if the Belt and Road Initiative should be considered as an offensive project? It’s unusual for a country trying to re-balance her economy to invest in railway lines, roads and ports?

Take, for example, commerce between the US and Japan. Does the US own any ports or roads in Japan?

They don’t need to. They own massive military bases and still hold massive sway over their foreign policy. Their aircraft carriers can dock in Japan’s ports whenever they wish. They don’t need to “own” any of Japan’s ports.

the 5-10,000 mile supply chain, whether in goods or LNG, whether EU-East Asia, EU-US, US-East Asia, etc. is going to make slowing greenhouse emissions impossible for the near term. barring the regulatory hammer coming down on freight emissions,or Star Trek levels of tech breakthrough.

where’s Michael Moore or Al Gore on this? guess it’s easier to rouse up the people on something about Trump.

These long supply lines are definitely a concern for efforts to reduce greenhouse emissions but the problem is the long delay before experiencing their impacts. I believe the long supply lines build a dangerous fragility into our economies. I fear what could happen when Saudi oil starts to run out. The long supply lines reflect the fragmentation and geographic spread of production. Most products represent a complex assembly of parts and processes spread around the globe. In many cases the want of a single part can shut down production — and inventories are kept ‘lean’ and ‘agile’ and so could run out quickly. Similarly the warehouses of goods, some of them needs not wants are remote from their points of consumption where again the inventories are kept ‘lean’ and ‘agile’. I think the major cities would be most vulnerable and most dangerous as jobs leave and food runs out.

A hypothetical I’ve been mulling — suppose the long supply lines for goods and services in the U.S. shut down. Would the U.S. be able to reassemble the many industries that have been fragmented? If transportation costs went up significantly how might that affect the location of various industries? I suspect economies of scale would scale very differently.

Thank you, informative article.

Noting the difference with ‘only 11′ v ’16+1’, China only needs to increase European membership in the BRI by about a third to avoid losing a qualified majority vote in the EU.

China only needs to increase European membership (16 currently?) in the BRI by about a third (5 or 6 more?) to avoid losing (losing? Does China have a quality majority now and what does it mean to say China has a qualified majority vote in the EU) a qualified majority vote in the EU?

What is European membership? Is that different from EU membership?

> China considers the southern and eastern European regions as strategic…. China also plans to build the Land-Sea Express Route – a network of railroad connections from the port to the western Balkans and northern Europe.

“Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World-Island controls the world.” –Halford Mackinder

Now, I’m not sure I believe this; it certainly didn’t work out that way for the USSR. And it’s not working out for NATO, now. But Xi and company might believe it.

Recalling the claim by the South China Morning Post a few months that the trade war between China and America was over a while back, and the US lost, reading this post, it seems like Europeans are acting as if they are at (trade) war with China. (Is it only their imagining? Has this or Russia, Russia, Russia, in the homeland here, been the reason UFO sightings have been down for a while now???)

Perhaps they don”t want to be like America and only find out (from SCMP) after they have been defeated.

@MyLessThanPrimeBeef [3:02 pm] “(Is it only their imagining? Has this or Russia, Russia, Russia, in the homeland here, been the reason UFO sightings have been down for a while now???)”

Are you making an oblique reference to Jung’s theories about UFOs or some variant of those theories? I don’t understand the connection between Russia, Russia, Russia and a decline in UFO sightings.

Maybe (I’m not certain about Jung’s theory about UFO’s, though I remember vaguely that it had something to do with our own projections maybe…).

If I’m reading my map correctly, the Chinese have to go through Greece, then Macedonia, then Serbia, then Hungary to get to the German speaking lands and Western Europe. So does Russian gas via Turkey. Think how vital Macedonia is then in the West’s efforts to block the Chinese and their very best friends, the Russians. America had already put the thumb on Bulgaria as far as a Black Sea gas pipeline goes, but they now seem to be trying to squirm out of that. It’s important for the ”West” to block pretty much all infrastructure projects in Eurasia: German Russian gas pipelines, Iranian Indian pipelines, trans Eurasian railroads, seaports etc. Watch what happens when the Russians propose building pipelines from Russia into N Korea then S Korea and then under the ocean to Japan. Hell hath no fury then an aging Hegemon scorned, or something like that. Sort of echos the so called pre WW1 Berlin to Baghdad-Basra Railway project generally opposed by the British: as per Wikipedia in a “light” article: “…the existence of the railway would have created a threat to British dominance over German trade, as it would have given German industry access to oil, and a port in the Persian Gulf.” All as per the Mackinder and now Brzezinski theory. When was the last time America proposed a grand infrastructure project tying in a north to south South American transportation project along with a trillion dollar high speed rail project in North America? Maritime powers try to prevent Continental powers from developing and connecting – at least according to some theories. I remember reading that in the last 12 years, China built 16,000 km of high speed rail. Why can’t Trump and Trudeau get together and build just one? Instead, they squabble about cheese – and not very good cheese at that.

Thanks for reminding me of this, puts the recent agreement between Greece and the “former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” on the name of “Northern Macedonia” in a new light of joint economic interest plus perhaps a bit of outside pressure.

Direct investment in EU maritime ports discussed here is one aspect of China’s trade with the EU, but direct investment in and shipments by rail are also growing rapidly. A Reuters article this week discussed the logistics bottlenecks of rail shipments of goods from China into Northern Europe via Belarus and Poland due to the rapid growth in trade volumes.

Please correct me if I am wrong.

I recall that Greece was forced to sell the port (or a large part of it) at Piraeus because the EU (i.e. German and French bankers) required austerity rather than some form of debt haircut.

And China was there as purchaser.

So the irony is that German/French bankers forced the sale of port to China by Greece. And now they realize that it will cost German/French shipping in the long run, probably a lot more money than debt haircut would have cost.

And of course, Greece lost its valuable asset.

Well, there’s nothing to stop them from nationalizing it back. I don’t think PRC could manage to send an expeditionary force to Greece.

That’s why I really don’t see anything all that threatening about what China’s doing. BRI is just run-of-the-mill capitalist globalism, not some sort of new empire.

Anyone who thinks the BRI is only about economics is being willfully blind. Economics is politics by other means. At best, these investments make Chinese goods more competitive in your home market, by reducing the logistics costs. At worst, they’re a means to gain sovereignty over a chunk of your nation. Witness what happened to Sri Lanka:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html

Lune, it might interest you to read this. Great example of how the NYT presented a very skewed view of the Sri Lankan deal.

http://www.moonofalabama.org/2018/06/chinas-port-in-sri-lankas-is-good-business-the-nyts-report-on-it-is-propaganda.html

Thanks for the link. It does seem that the port is getting more business than the NYT article would suggest. However, it remains true that Sri Lanka has essentially given up sovereignty over that port, in exchange for debt forgiveness. Regardless of whether it’s ultimately profitable or not, that’s the real issue. The caveat that China can’t use it for military purposes unless given “permission” by Sri Lanka is just a fig leaf: who believes the government would stand against China if it threatens retaliation if it doesn’t get that permission?

There are also other troubling aspects that the article you cite doesn’t refute. For example, the requirement for single source no-bid contracts which must go to a state-owned Chinese company, the bribes paid by China to keep their pliant choice for prime minister in power, and the high interest rates charged on such debt, much higher than the vast majority of development aid from other countries.

Focusing on the narrow issue of whether the port will ultimately be economically beneficial neglects the very real domestic and geopolitical problems that the port has already spawned.

China is gaining significant control of Australian ports as well. Particularly interesting is 100% control of Port of Darwin, an important naval base in the region.

Good summary from https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/au/pdf/2017/demystifying-chinese-investment-in-australia-may-2017.pdf

The sale of the Port of Newcastle for

AUD 1.75 billion in 2014 saw the China Merchants Group take 50 percent ownership

of the lease. The following year, the Port

of Darwin was sold for AUD 506 million to Landbridge Group, owned by Chinese billionaire Ye Cheng. These are crucial assets for Australian trade, with the Port of Darwin exporting

35 percent of Australian livestock and the

Port of Newcastle exporting 40 percent

of Australia’s Coal13.

2016 saw similar interest, with the Port of Melbourne sold for AUD 9.70 billion to a consortium that included a 20 percent holding by China Investment Corp (CIC), China’s

AUD 200 billion sovereign wealth fund. The sale has added signi cant value for the State and Federal Government and for the investors who are expected to tip AUD 6 billion into upgrading the facility over the life of the 50-year lease.

The Port of Melbourne is Australia’s largest container port, vital for incoming manufactured products as well as Victorian exports. It accounts for 13.3 percent of Australia’s AUD 3 billion a year Australian port industry and is expected to grow at an above-average 8.5 percent annually.

CIC’s investment in 20 percent of The Port of Melbourne lease attracted signi cantly less attention than the wholly Chinese-owned Landbridge Group when it bought 100 percent The Port of Darwin lease in 2015. This re ects the nature of the asset, which is less critical for the Australian Navy. It also re ects the virtue of a diversi ed ownership structure in a consortium that is only 40 percent Australian-owned.