By Simone Tagliapietra, Research Fellow at Bruegel, Adjunct Professor of Global Energy at the Johns Hopkins University SAIS Europe and Senior Researcher at the Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei. Originally published at Breugel.

Since 2015, Nord Stream 2 has been at the centre of all European discussions concerning the EU-Russia relations. But as endless political discussions in Europe are being held on this pipeline project, the pipes of another similar Russian pipeline project – Turk Stream – are already being laid by Gazprom at the bottom of the Black Sea. This piece looks at these developments, analysing their strategic impacts on Europe.

For Europe, thinking about energy security means thinking about Russia. First in January 2006 and then in January 2009, gas pricing dispute between Russia and Ukraine led to the halt of Russian gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine – its primary transit route. This generated economic damages for Europe, notably in South-Eastern European countries heavily dependent on Russian gas for both electricity generation and residential heating.

Europe responded to these gas crises by adopting an energy security strategy mainly focused on reducing its dependency on Russian gas supply. The high priority given to Russian gas supplies arose because: (1) gas represents about one quarter of the European energy mix; (2) about one third of this gas is imported from Russia; and (3) in contrast to oil or coal, it is not possible to bring large amounts of gas to where it is needed if the corresponding infrastructure is not in place.

In the midst of the 2014 Ukraine crisis, concerns about a potential politically motivated disruption of all European gas supplies from Russia lifted again energy issues to the top of the European agenda and led to the creation of the EU Energy Union.

While Europe developed its energy security strategy, Russia also developed its own strategy, primarily aimed at maintaining its share in the European gas market in the future. To do this, Russia primarily intends to secure its supplies by diverting all its gas transit to Europe away from Ukraine by 2020.

In view of achieving this target, in 2015 Gazprom signed an agreement with major European energy companies to construct Nord Stream 2, a pipeline aimed at diverting away from Ukraine 55 billion cubic metres per year (Bcm/y) of gas transit, by expanding the existing direct link – Nord Stream 1 – between Russia and Germany.

Since 2015, Nord Stream 2 has been at the centre of all European discussions concerning the EU-Russia relations in general, and the European energy security in particular. But as endless political discussions in Europe are being held on this pipeline project, the pipes of another similar Russian pipeline project – Turk Stream – are already being laid by Gazprom at the bottom of the Black Sea.

Launched by Russia president Vladimir Putin in December 2014 during a state visit to Turkey, Turk Stream is a pipeline projected to deliver 31.5 Bcm/y of gas to Turkey and Europe. As in the case of Nord Stream 2, also this project is not aimed at carrying additional volumes of gas, but just to partially replace flows that currently reach Turkey and Europe through Ukraine.

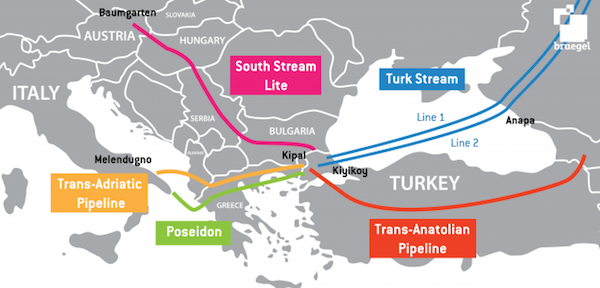

Turk Stream comprises two lines, each with a capacity of 15.75 Bcm/y. Line 1 is designed solely to supply Turkey, while Line 2 is intended to deliver gas to Europe.

After a year of works, construction of the offshore part of Line 1 was completed on April 30th 2018; the onshore parts remain under works. With the construction of Line 2 also progressing, both lines of Turk Stream are expected to be finalised by the end of 2019.

However, due to EU anti-monopoly rules Gazprom, as a supplier, is prohibited from operating gas pipelines inside the EU. The Russian company is thus currently exploring potential alternative options with European gas grid operators for bringing the 15.75 Bcm/y capacity of Turk Stream’s Line 2 to European markets.

The first option would be to link Turkey and Austria with a pipeline running through Bulgaria, Serbia and Hungary. This pipeline has been dubbed ‘South Stream Lite’, as it would roughly follow the path of the proposed South Stream pipeline, which was scrapped by Russia in 2014 following opposition from the European Commission.

Not by coincidence, elements of the original South Stream project are recently being revived by Bulgaria and Serbia. Bulgarian gas grid operator Bulgartransgaz recently acquired a series of assets with the aim of creating a Balkan gas trading and transport hub. Bulgartransgaz and Serbia’s Gastrans have also started to explore gas companies’ interest in utilising potential pipelines connecting Bulgaria to Hungary. From Hungary, pipes could run to Austria via planned or existing routes.

The second option would be to link Turkey and Italy with a pipeline running through Greece. The feasibility study for such a pipeline was conducted in 2003 by Greece’s public gas supply company DEPA and Italy’s energy company Edison. The development of the project – named Poseidon – was then covered by an intergovernmental agreement signed in 2005 between Greece and Italy.

When, in 2013, the group of companies operating Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz II gas field – which constitutes the main source of the Southern Gas Corridor – chose the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) to link the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) to Italy, the Poseidon project was eclipsed. It has only recently been revived, based on the potential opportunities of linking Turk Stream to Italy, as well as a potential pipeline running from Israel to Greece – the East Mediterranean pipeline – to Italy.

The third option would be to make use of the spare capacity of the TAP. The 800km-long pipeline – currently under construction – will serve to deliver 10 Bcm/y of Azeri gas to Italy, starting in 2020. However, the TAP’s capacity can be expanded to 20 Bcm/y with the addition of new compressing stations. The pipeline also has a physical reverse-flow feature, allowing gas from Italy to be diverted to South East Europe if energy supplies are disrupted or more pipeline capacity is required to bring additional gas into the region.

This flexibility could make the TAP a very attractive option for Turk Stream. However, considering that Turk Stream’s Line 2 is not intended to deliver an additional supply to Europe, but just to divert part of the existing supply that currently enters Europe via Ukraine, existing contracts between Gazprom and European partners – such as Italy – should also be taken into account.

In this regard, South Stream Lite could offer the most viable option for Gazprom, as it would not require the change of existing contracts with European partners, on which the delivery point for contracted supplies is set at Austria’s Baumgarten. Gazprom will certainly announce a decision on the preferred route very soon, as it targets first gas flows to Europe via Turk Stream as soon as early-2020.

The speed of these developments should not surprise anyone. Russia seeks to cut its current 90 Bcm/y of gas transit via Ukraine down to 10-15 Bcm/y after 2019. With Nord Stream 2 under fire from European policy makers, Turk Stream clearly becomes an essential bargaining chip for Russia in the ‘great-game’ of Ukrainian gas transit.

Didn’t Germany kill that project? If I remember well they threatened and pushed Bulgaria and Romania to abandon it and they bribed Italy by letting them participate in Nord Stream 2.

The original South Stream pipeline project was killed indeed, but by politics. Economics still require that pipeline, hence the ongoing ‘replacement’ discussion as described above.

Gas transit through the Ukraine always was a dodgy process and it has happened that the Ukraine simply swiped what it wanted for its own needs and stiffed those customers in Europe who had actually paid for the gas. Of course they put the blame on Russia for the missing gas. When Europe created the EU Energy Union it made things even more difficult for Russia as the Energy Union was trying to abrogate the right to have contracts already written and in use retrospectively fulfill new requirements to align with their new policies.

After the Ukrainian putsch, the US thought that it had its hand on the gas pump as all lines went through the Ukraine and they controlled the Ukraine. The Russians are now bypassing that unhappy country. Nord Stream 2 will probably be finished as Germany needs this gas for its energy supply and are not about to cripple themselves to satisfy the latest whim from Washington. It is the Turk Stream which is the interesting one to watch. Turkey is already defying the US and the EU about building this line as there are far more upsides than downsides. For a start there will be the transit fees that they will receive that will help fill Turkish coffers which will be appreciated as they are experiencing economic difficulties at the moment.

Having Russian gas transit also helps Turkey’s position in southern Europe politically as all those countries know where that gas has to pass through. Northern Europe did not want this project to go through in spite of pushing for Nord Stream 2 which exasperated a lot of countries like Austria and Greece. They were originally going to get their gas via Bulgaria but the US and the EU threatened them until they backed out of the project. Bulgaria must be very unhappy now as instead of earning hard cash with transit fees, they will only get transit fees for the South Stream Lite pipe line.

Turkey may be able to get the countries in southern Europe to support its policies more as the northern Europeans have always made clear that there is no place for them in the EU after some thirty years negotiating with them about entry. Greece may find themselves in an uncomfortable position as they have been receiving gas from Turkey since 2007 but they have had a lot of trouble about islands disputed by Turkey for years now. In fact, I am wondering if you can say that political alliances are to be found downstream of gas supply lines.

Yes. The major people who seem to be against Nord Stream are Ukraine, Poland, USA (neo cons like McCain and friends) and now Trump representing America’s LNG interests. Ukraine and Poland are complaining that their national security is threatened by Nord Stream . What? Seems that Germany has no problem with being dependent on Russian gas, but Ukraine, Poland, and USA are so concerned about poor poor Germany’s energy security and national well being that the Germans should continue to route their Russian gas through Ukraine. Then, Russian gas becomes OK.