By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and previously an Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Originally published at Bruegel

Economists have been discussing the implications of the rise of the intangible economy in relation to the secular stagnation hypothesis, and looking more generally into the policy implications it has for taxation. We review some recent contributions.

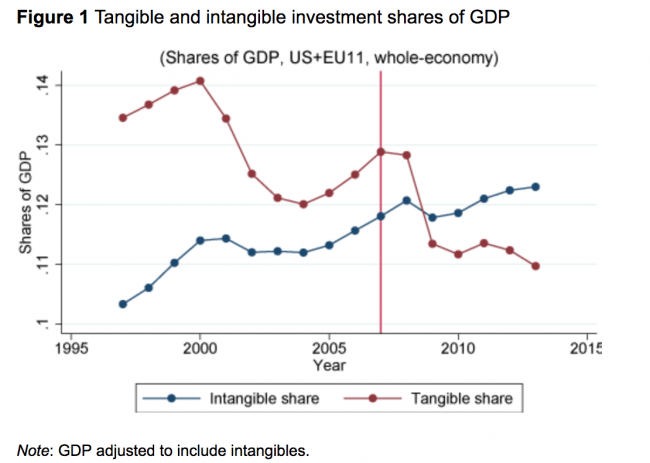

Haskel and Westlake argue that the recent rise of the intangible economy could play an important role in explaining secular stagnation. Over the past 20 years, there has been a steady rise in the importance of intangible investments relative to tangible investments: by 2013, for every £1 investment in tangible assets, the major developed countries spent £1.10 on intangible assets (Figure below). From a measurement standpoint, intangibles can be classified into three broad categories: computer related, innovative properties, and company competencies. Intangibles share four economic features: scalability, sunkenness, spillovers, and synergies. Haskel and Westlake argue that – taken together – these measurements and economic properties might help us understand secular stagnation.

The first link between intangible investment and secular stagnation is,according to Haskel and Westlake, mismeasurement. If we mismeasure investment, then measured investment, GDP, and its growth might be too low. Secondly, since intangibles tend to generate more spillovers, a slowdown in intangible capital services growth would manifest itself in the data as a slowdown in total-factor productivity (TFP) growth. Thirdly, intangible-rich firms are scaling up dramatically, contributing to the widening gap between leading and lagging firms. Fourthly, TFP growth could be slower because intangibles are somehow generating fewer spillovers than they used to.

Similar arguments have been proposed before. Caggese and Pérez-Orive argued that low interest rates can hurt capital reallocation in addition to reduce aggregate productivity and output in economies that rely strongly on intangible capital. They use a model in which productive credit-constrained firms can only borrow against the collateral value of their tangible assets and there is substantial dispersion in productivity. In a tangibles-intense economy with highly leveraged firms, low rates enable more borrowing and faster debt repayment while also reducing misallocation and increasing aggregate output. Conversely, an increase in the share of intangible capital in production reduces the borrowing capacity and increases the cash holdings of the corporate sector, which then switches from being a net borrower to a net saver. In this intangibles-intense economy, the ability of firms to purchase intangible capital using retained earnings is impaired by low interest rates because they increase the price of capital and slow down the accumulation of corporate savings. As a result, the emergence of intangible technologies, even when they replace less productive tangible ones, may be contractionary.

Kiyotaki and Zhang examine how aggregate output and income distribution interact with accumulation of intangible capital over time and across generations.. In this overlapping generation economy, the managers’ skills (intangible capital), alongside their labour, are essential for production. Furthermore, managerial skills are acquired by young workers when they are trained by old managers on the job. As training is costly, it becomes an investment in intangible capital. They show that, when young trainees face financing constraints, a small difference in initial endowment of young workers leads to a large inequality in the assignment and accumulation of intangibles. A negative shock to endowment can generate a persistent stagnation and a rise in inequality.

Doettling and Perotti argue that technological progress enhancing the productivity of skills and intangible capital can account for the long term financial trends since 1980. As creating intangibles requires a commitment to human capital rather than physical investments, firms need less external finance. As intangible capital become more productive, innovators gain a rising income share. The general equilibrium effect is a falling credit demand, consistent with falling trends in both tangible investment and interest rates. Another effect is a boost to asset valuation and rising credit demand to fund house purchases. The combination of rising house prices and increasing inequality raises household leverage and default risk. While demographics, capital flows and trade also contribute to a savings glut and changes in factor productivity, the authors believe that only a strong technological shift towards intangibles can account for all major trends, including income polarization and a reallocation of credit from productive to asset financing.

Intangibles raise questions on the policy side too. Reviewing Haskel and Westalke’s book, Martin Wolf, refering to the four features of intangible assets that the authors identify argues that, taken together, they subvert the familiar functioning of a competitive market economy, most importantly because intangible assets are mobile and thus hard to tax. This transformation of the economy demands, according to Wolf, a retxamination of public policy around five challenges: First, frameworks for protection of intellectual property are more important, but intellectual property monopolies can be costly. Second, since synergies are so important, policymakers need to consider how to encourage them. Third, financing intangibles is hard, so the financial system will need to change. Fourth, the difficulty of appropriating gains from investment in intangibles might create chronic under-investment in a market economy, and government will have to play an important role in sharing the risks. Finally, governments must also consider how to tackle the inequalities created by intangibles, one of which is the rise of super-dominant companies.

The problem is certainly relevant for Europe. Guntram Wolff has a chart showing that Germany is under-performing in intangible investments compared to its peers in France and the US and is on par with those of Italy. In a separate post, he also discusses how this relates to the mechanics of German current account surplus.

Reviewing the same book, marxist economist Michael Roberts argue that the title (“Capitalism without capital”) is inappropriate to describe the intangible economy. For Marxist theory, what matters is the exploitive relation between the owners of the means of production (whether tangible or intangible) and the producers of value ( whether manual or ‘mental’ workers). From this perspective, knowledge is produced by mental labour but this is not ultimately different from manual labour. The point according to Roberts is that discoveries, generally now made by teams of mental workers, are appropriated by capital and controlled by patents, intellectual property or similar means. Production of knowledge is then directed towards profit. Under capitalism, the rise of intangible investment is thus leading to increased inequality between capitalists, and the control of intangibles by a small number of mega companies could well be weakening the ability to find new ideas and develop them. Therefore, we have the position where the new leading sectors are increasingly investing in intangibles while investment overall falls along with productivity and profitability. This, according to Roberts, should suggest that Marx’s law of profitability is not modified but intensified.

Roger Farmer thinks that intangible investments influence company profitability. If technology companies’ profits are continually reinvested as intangibles, earnings may never appear as output in GDP statistics, but they will affect the company’s market value. For government leaders concerned with providing goods and services during a period of slow growth, getting a handle on this unmeasured GDP is essential. He thinks that we must reevaluate how tax revenue is raised. If all income were taxed at the same rate, intangible investments made by companies would still generate revenue in the form of taxes paid by the companies’ wealthy owners. The alternative – to maintain the status quo – will only ensure that as growth in the intangible economy intensifies, current revenue gaps will eventually become gaping holes.

Zia Qureshi argues that in today’s increasingly knowledge-intensive economy, policies should aim to democratize innovation, thereby boosting the creation and dissemination of new ideas. This implies overhauling an intellectual-property regime that is moving in the opposite direction. Some argue that the patent system should simply be dismantled, however, that would be too radical an approach. What is really needed is a top-to-bottom reexamination of the system, with an eye to changing excessively broad or stringent protections, aligning the rules with current realities, and enabling competition to drive innovation and technological diffusion. One set of reforms to consider would focus on improving institutional processes, such as ensuring that the litigation system does not favor patent holders excessively. Other reforms concern the patents themselves and include shortening patent terms, introducing use-it-or lose-it provisions, and instituting stricter criteria that limit patents to truly meaningful inventions. The key to success may lie in replacing the “one-size-fits-all” approach of the current patent regime with a differentiated approach that may be better suited to today’s economy.

Thinking from an environmental perspective, perhaps rise of intangible economy is good. However recovery of value on the tangible side seems likely in the, possibly near, future. Due to a growing scarcity and demand for things like food, clean water, shelter.

If knowledge is locked up behind a paywall, that includes knowledge about environmental limits and methods of staying within them. I have a hard time imagining how this could be good for the environment in the long run.

jobs being created on the margin are min wage jobs. THis is obviously because the investment opportunities being filled are low ROI ones (pizza stores etc).

So, new entrants to the job market, or the ones who lose their high paying ones, are facing a difficult situation, as the jobs in excess are basically that dont’t and can’t, pay well.

So, the article asks the question- Is there a correlation between the rise of intangibles and secular stagnation?

First step is to clearly define both terms

Secular Stagnation (SS)…ehhh …hmm…ok so precisely defining this term is beyond my pay grade. At best, it seems using this term is about as precise as saying the Pacific Ocean is big. Actually, might be quantitatively easier to measure the volume of the Pacific Ocean (assuming everyone can agree where one ocean ends and the next one begins) than defining SS in a quantitative fashion.

Second term – intangibles… while it may be easier to define individual types of intangibles, assigning a fair value to them at any moment in time is difficult. (And I believe their actual value probably even changes from each moment to the next).

Two of the economists cited in the article classify intangibles “…into three broad categories- computer related, innovative properties and company competencies….”. I’d argue that could be reduced to just two- company competencies (e.g. goodwill, trade secrets, customer relationships, brand recognition, etc.) and protective monopolistic rights (e.g. patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain names, non-competes, broadcast rights, etc.). Others might see more categories.

Next how does one measure the value of intangibles (cost vs fair value)? Well, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) takes two separate perspectives

1. Internally generated intangibles- these costs, with some minor exceptions, and which may sometimes be difficult to identify, are expensed as incurred. So, they do not get carried on the balance sheet.

2. Intangibles acquired from third parties- these costs can be identified and capitalized (carried on the balance sheet) as an asset. Note the asset value being carried relates to the cost. Then this value is subject to periodic downward revaluations.

How is it possible to deduce the value of economy-wide intangibles in a reliable fashion, when a good portion of their values are not being reported anywhere? And how they should be defined?(I love how two of the economists cited in the article were able to plot precise numbers for this on the graph that was presented)

So, with all this as a backdrop, how does one resolve quantitatively, whether there is a correlation between SS and intangibles. I don’t think it’s possible while both variables remain unknowns.

However, qualitatively, I don’t disagree that there is a correlation.

From a micro perspective, I’ve seen companies buy other companies, and have been able to compute the costs associated with goodwill in a precise fashion using GAAP.

But from my own experience, one can’t possibly tell if the ACTUAL value of the goodwill is equal to or higher than what has been booked. My own homegrown definition of goodwill value is… that it should be equal to the present value of the cumulative future incremental benefits that will be realized solely as a result of the acquisition. Heh…so truth be told you need a working crystal ball to truly validate that one. The way it works in the real world, goodwill is periodically reevaluated and should be adjusted downward only if there is evidence of impairment. This involves subjectivity and judgment on an ongoing basis.

Many times, history has shown that goodwill has to be written down. Why? Easy answer…turns out the company usually overpaid for the acquisition. Same as when investors grossly overpaid for many tech stocks in the mid 1990’s. What is the consequence of this? Generally, the company is more leveraged than otherwise would have been the case, or at the very least, shareholder resources available to it have been greatly reduced (if it’s closely held) due to the overpayment. Consequently, there is less capital available to be invested in people, research, whatever. Not an economist, but from an anecdotal perspective, it can be seen how this could result in a negative effect on the economy as a whole.

So, I agree with the opening correlation in the article. But to me, it would be clearer to restate the proposition as something much simpler that companies should follow … Don’t overpay for the assets you acquire. (Note to self: why again did I bother to go to all this trouble to state the obvious?)

Remember when Eastman Kodak attempted to monetize some of their intangibles?

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/20/business/kodak-to-sell-patents-for-525-million.html

A quote: “On Wednesday, the sale was finally announced, but instead of bringing as much as $2.6 billion as Kodak once predicted, the selling price was far short of that amount, at about $525 million. The buyer was a consortium that includes many of the world’s biggest technology firms, among them Apple, Google, Facebook and Samsung Electronics.”

Perhaps one should also factor in “negative intangibles” such as when knowledge is quietly transferred to a foreign country in order to build a US/European based company’s products.

This can represent a “train your company’s competition to better compete against your company in the future” scenario.

But it may not show up for several quarters/years.

Good point…wonder how our econoworld friends capture that data

Valuing Intangibles: This is behind the current push to patent more and more things (looks-and-feels, shapes, colors, algorithms, processes, user interfaces, application-program interfaces), and to extend copyright terms. You can value an intangible asset by the present value of the cash flow you anticipate getting from owning it.

In the past, patents have mainly got their value from the value of physical goods that depend on them, but if softer and softer things get patented, that will change. See Techdirt’s Stupid Patent of the Week(or Month or whatever it is) for the latest progress down this road.

On the good side, we don’t exhaust as much/many of the earth’s resources by growing the market in looks-and-feels, etc. On the bad side, it’s now a land-grab, and lots of things we thought were ordinary parts of life are going to be alienated from us, until we pay to get them back.

What utter nonsense. The totally dominant form of “intangible capital” is “intellectual property,” i.e.., state-enforced monopolization of massive amounts of knowledge and technology. And all those “capital constrained” monopolist corporations “investing” in intangible capital, what are they really doing with their “incomes?” But you know already–they are spending hundreds of billions, nay trillions, on buying back their own stock.

Much of this intellectual property is taking from what would have previously been the intellectual commons, or even stealing it from the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples, or taking it for free from academics then charging monopoly prices for it in academic journals. Then the corporations make sure the patent/copyright timeframes get extended if they are in danger of expiring (aka the “Micky Mouse” rule of copyright extension).

It is an intellectual “land grab” as another commentator put it. It makes a few rich and the rest poorer – both having to pay the monopoly rents and having innovation held back as more and more knowledge is not freely available. It also directly hinders the development of the poorer countries as they are stopped from leapfrogging up the technology ladder by a wall of patents and TRIPS treaty restrictions.

Yes, when I have done online research within the last year, I notice a lot more papers are locked behind the ResearchGate paywall. I gather there was a lawsuit.

Problem is, there’s a 90%+ chance a given paper isn’t going to deliver anything relevant to my specific line of inquiry, so paying for it in advance of scanning the document is out of the question. So the intellectual commons that was opened up for 30+ years by the Internet is now shrinking again, fenced and deeded.

EFF cofounder John Perry Barlow warned of this in his seminal essay “The Economy of Ideas” (1994) https://www.wired.com/1994/03/economy-ideas/

starting with a fitting quote from Thomas Jefferson:

If Nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of everyone, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it.

Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me.

That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by Nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density at any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation.

Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.

Barlow: “Since we don’t have a solution to what is a profoundly new kind of challenge, and are apparently unable to delay the galloping digitization of everything not obstinately physical, we are sailing into the future on a sinking ship.”

Re: Martin Wolf’s 5 policy issues: yes, yes, yes, yes, and yes.

Policy is out of synch, I am increasingly convinced, because too few policy makers bring the kind of ‘intangibles’ experience that would enable them to think more clearly. Judges — whose income is premised on salaries, and whose basis for judgment tends to be ‘precedent’ — are the least well-prepared people to be making decisions about all of this. Attorneys are really going to have their hands full trying to help judges and policy makers grasp the fluid, somewhat ephemeral, nature of the core issues that Wolf lays out.

If we could view the existing economic thinking as Copernican, we need to shift to a quantum physics view including wormholes, dark matter, and a lot of shifting gravitational fields. That is intellectually more rigorous, and challenges financial media, blogs, economists, and policy makers to do more ‘heavy lifting’. But that seems to be the path toward greater shared prosperity.

This is amazinly funny. I clearly remember the UK news on TC (auntie BBC)m reporting on trade, which was always in deficit, and then state that the deficit was balanced by “intangible exports.”

I later discovered that “Intangible Exports” were, to a large extent tax evasion, by wealthy people outside the UK.

A simple definition of what tangible versus intangible assets are, at the beginning of the article, would make this less gobbledygook to the average reader.

Otherwise, it’s just another insider article for the financially versed elite.

Intangible Export = Money Returned to “Exporting Country,” for some service.

When Wachovia Bank laundered half a Billion or more of drug money, the fees from that work were an “Intangible Export.”

When I see the words “Intangible Export” I think tax evasion, or money derived from other crimes.

How about the intangible power of double entry book keeping to create some 97% of our money by rationing it to who, what, when, how much, ex-nihilo at interest. Oh that’s right, I forgot that’s not important enough to ask private for profit commercial banks to responsibly direct this social abstract for nominal gdp growth. Nor should this intangible be actually taught to students learning economics. Will just call that a legally misleading term like a deposit. NIA accountants will try hard to come up with some intangible mathematical formula to show that this process has added value magically.