By Lambert Strether of Corrente.

I had thought this post would turn out to be a review of the literature, but I can’t deliver on that, exactly, as I am about to demonstrate. When I read that a coyote referred to the migrant he was smuggling as a “package,” I was immediately reminded of the Atlantic slave trade, with its human “cargo.” It has always seemed reasonable to me to conceptualize the Atlantic Slave Trade — the triangular trade — as a supply chain, perhaps because I write about shipping and supply chains a lot. And so it seemed reasonable to conceptualize the structure behind our current “migrant justice” discourse in the same way: A human supply chain. This would have the advantage, by focusing on the international working class as a whole, of avoiding siloed victimology narratives[2] like “forced labor” — what, exactly, is not forced about the global norm of wage labor? — perhaps opening the door to less tendentious discussions of migration policy. As it turns out, that approach has problems. To begin with, the categories on labor migration are bad, meaning that the numbers are bad. From the UN International Organization for Migration’s (IOM) data portal:

There is no internationally accepted statistical definition of labour migration. However, the main actors in labour migration are migrant workers, which the International Labour Organization (ILO) defines as:

“… all international migrants who are currently employed or unemployed and seeking employment in their present country of residence.” (ILO, 2015).

The United Nations Statistics Division (UN SD) also provides a statistical definition of a foreign migrant worker:

“Foreigners admitted by the receiving State for the specific purpose of exercising an economic activity remunerated from within the receiving country. Their length of stay is usually restricted as is the type of employment they can hold. Their dependents, if admitted, are also included in this category.” (UN SD, 2017).

While migrant workers are often also international migrants, not all are… It is important to note the difference between the definition of a foreign migrant worker and an international migrant. An international migrant is defined as:

“any person who changes his or her country of usual residence” (UN DESA, 1998).

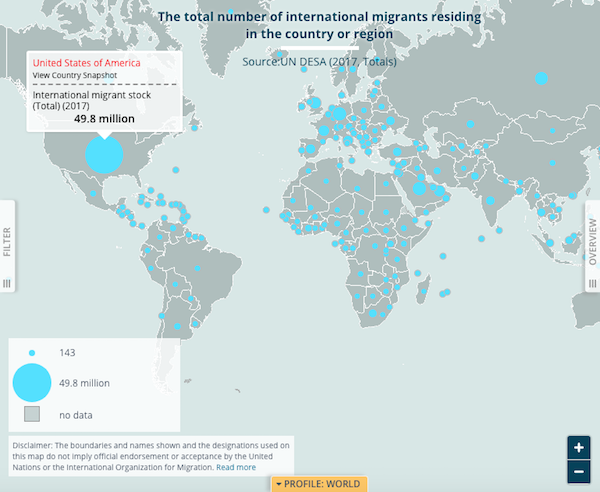

We can, however, get the big picture of the scale of migration globally. Again from the IOM:

So it turns out that globally the United States is, er, exceptional — assuming the numbers aren’t so bad as to completely distort our role — for reasons I won’t speculate on today. Rounding freely, we have 50 million migrants[3] in the United States in toto, abstracting away all the categories like legal, illegal, asylum seeker, economic migrant, and so on.

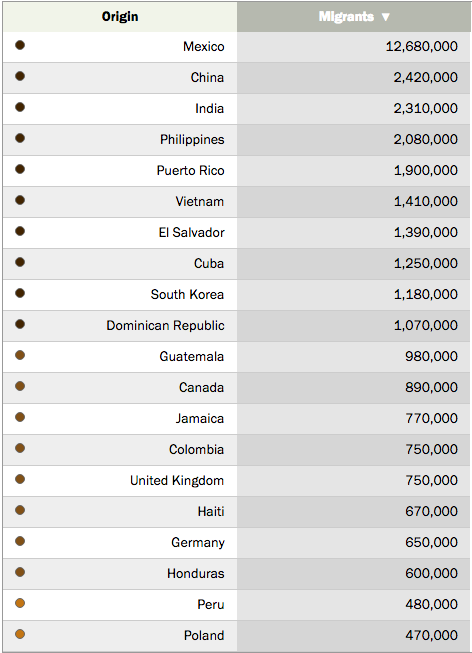

And here are the countries our migrants come from, as of 2017. From Pew Research:

(This is our stock, as it were; flows differ year-to-year. The 1800 families in the current “family separation” controversy are from Central America, not Mexico.)

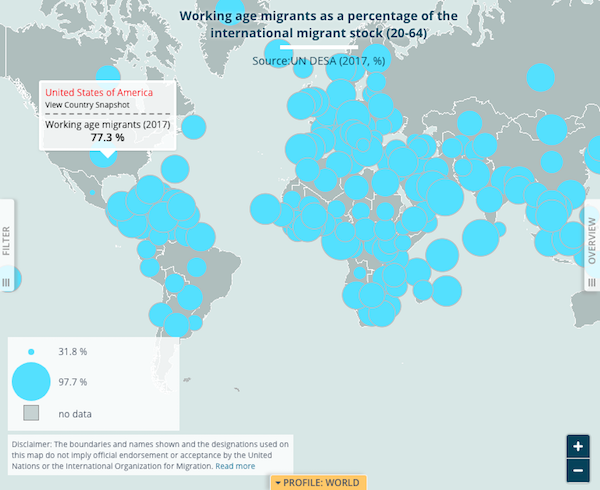

Still at the same level of abstraction, if we use “working age” as a proxy for “working class,” we can guess as the scale of labor migration into the United States:

(Note from the caption that the the blue bubbles are percentages, not absolute numbers. Globally, most migrants are working age. It’s just that in the United States we have many, many more of them.) 75% of 50 million is ~37 million working class migrants.[4] Again, we can think of all the categories (legal, illegal) as different aspects of the same supply chain, in the same way that different cargoes have different materials handling and paperwork requirements. These would be impressive numbers, even if we were talking about retail goods moved in shipping containers.

With all this as background, I was excited to review the literature on labor migration as a human supply chain. So I started, and came up with material like this, from Logistics Management:

LMS: Optimizing the human supply chain

It’s no secret that labor costs eat up a big part of any company’s bottom line. And unlike some other major expenses—the cost of raw materials, overhead and utilities—human productivity can be extremely difficult to gauge, control and optimize. Without the right tools in place, warehouse managers choose to fly by the seat of their pants when it comes to “human supply chain” management, hoping that their tactics pay off in the long run.

Now for the good news: Technology has put effective labor management within reach for companies of all sizes and across all industries.

No. A “human supply chain” for managing workers within the firm is not what I want; in fact, perspectives from within or between firms seems to be a common element shared by most people using the term. Take this, from Verité:

Bottom of the Supply Chain: The Tipping Point for Migrant Worker Policies

Have we reached a tipping point in promoting ethical recruitment in global supply chains?

I think it’s pretty safe to say that we have not—but there has been a lot of good work recently among global companies and the private sector on the subject, most of it focused on the recruitment fees charged to workers.

The recent migrant worker policy adopted by Patagonia, the US outdoor clothing company, is a case in point. It explicitly prohibits suppliers from charging fees, expenses or deposits to workers for recruitment or employment services, echoing similar policies adopted by Apple and HP in the electronics industry late last year… After so many years on the margins, unethical recruitment practices and related issues of debt bondage and forced labor are now taking center stage in supply chains, and industry and multi-stakeholder initiatives involving business.

No. Verité escapes the victimology trap by focusing on recruitment as such, by firms, which applies to all workers across the board, but they consider the workers as inputs to the global supply chain of manufactured goods, and do not consider the supply of those human inputs (“cargo,” “packages”) as constituting a supply chain in and of itself. Hence they can only think in contractual, and not class terms. (It’s a bit like trying to dope out the supply chain for the iPhone by examining bills of lading.)

Or this, from HR Today:

The Human Supply Chain

In Talent on Demand, [Wharton management Professor Peter Capelli] espouses a strategy of asking questions about human capital requirements that borrows from the questions supply chain managers typically ask, such as “Do we have the right parts in stock?” or, “Do we know where to get these parts when we need them?” and, “Does it cost a lot of money to carry inventory?”

Asking such questions leads to simulations or scenarios that provide a more compelling way to assess uncertainty than the traditional static forecasting model. For example, take the question about inventory. With talent management, organizations will often say they have a “deep bench.” Yet a deep bench in a supply chain is a costly way of preparing for demand. “The same applies to traditional succession management—you’re paying people to essentially ‘sit on the shelf,’ ” says Capelli.

Instead of targeting a specific person for a particular job five years down the line, Cappelli recommends creating a diversified pool of talent. He borrows this concept from portfolio management theories, an approach whereby the risks of certain investments falling in value are, ideally, offset by different investments that will rise in value.

No. Executive “talent management” by the firm is not my use case. (This is a bit like trying to dope out the supply chain for the iPhone by an org chart.)

And then there’s this, from Information Week:

Optimizing the Human Supply Chain

In its “workforce optimization” initiative, IBM is taking a supply chain management approach to solving these problems, cataloging skill sets as human inventory and applying the same supply chain technology used for the company’s hardware to respond quickly to short-term needs and plan for long-term demands. This approach makes sense, says Bruce Richardson, chief research officer at AMR Research. “As happens in a supply chain, you can find you have too much of one ‘product’ and not enough of another in the labor chain,” he says.

When IBM started the project in 2004, the company saw that the first barrier to development of a common “skills-supply” database was a lack of common language to define skills and job roles — a “manager” in one division might be a “leader” in another, for instance. IBM developed a skills taxonomy structured on a hierarchy of 500 job roles and skill sets. In the short term, it planned to use that taxonomy and ETL tools to translate skill data into a common language when loading the new database. In the long term, the taxonomy would drive standardization in job descriptions. All 320,000 IBM employees will be identified by mid-2006 and, once subcontractors and suppliers are added, IBM expects to have one million individuals represented in the database.

No. Professional “skill data” by the firm is not my use case. (This is a bit like trying to dope out the supply chain for the iPhone without looking for the suicide nets.)

And then there’s this, from Jeremy Prepscius of BSR, a sustainability consultancy, in GreenBiz:

Transnational migration is a market, of course: labor supply (made up of migrants) fills the labor demand of employers. In a functioning marketplace, demand and supply meet and reach an agreement on price (in this case, wages, benefits and working conditions) within the guidelines of the law and other contexts, such as collective bargaining agreements.

However, this labor-migration market is failing because the basics of a market relationship are not happening. This failure has serious consequences, which can involve human trafficking, forced and bonded labor [victimology], and human rights violations.

Why is this market failing? The key to any market correctly operating is information — both buyer and seller, or employer and employee, need to understand the bargain they are striking. In this case, however, migrants all too often lack the information necessary to make informed decisions, raising the risk of exploitation.

Employers are often in the same boat, lacking information about their new hires and the recruitment processes that bring them to the employer. Information arbitrage, where the middleman exploits these gaps in knowledge, exists at many steps in the recruitment process and is often connected to graft, corruption and exploitation of the migrant.

As this market crosses borders and regulators, local actors often put their interests above broader market needs. Consequently, a well regulated, functioning market is very difficult. When this market fails, the weakest actor — the individual migrant — suffers most, as he or she bears the vast majority of the costs, in the form of debt, deportation or other consequences.

Businesses can overcome these market failings, but this requires investments that are neither easy nor free. However, leading companies are taking these steps, including instituting due diligence on and monitoring recruitment agents, conducting interviews with migrants, shifting migration costs from migrant to employer and repaying debts incurred by migrants.

These steps help avoid bonded labor, ensure successful migration experiences and protect the rights of migrants. And these steps can create significant business value, such as reputational enhancement with customers, risk mitigation and workforce retention.

No, though this is about as good — and as neoliberal — as it gets (even though the phrase “human supply chain” is not used). I don’t agree that “The key to any market correctly operating is information.” For one thing, “correctly” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. For another, the key to the way markets operate is not information, but power. I mean, does Prepscius really believe that “reputational enhancement…, risk mitigation[,] and workforce retention” pose “significant business value” when put beside profit?

All of which brings me to the single, solitary on-point source I was able to find: Fordham’s Jennifer Gordon’s “Regulating the Human Supply Chain,” 446 Iowa Law Review, Vol. 102:445-503 (pdf)[5]. I highly recommend that anybody who has read this far give Gordon a look. From the abstract:

In 2015, the number of migrant workers entering the United States on visas was nearly double that of undocumented arrivals—almost the inverse of just 10 years earlier. Yet notice of this dramatic shift, and examination of its implications for U.S. law and the regulation of employment in particular, has been absent from legal scholarship.

This Article fills that gap, arguing that employers’ recruitment of would-be migrants from other countries, unlike their use of undocumented workers already in the United States, creates a transnational network of labor intermediaries—the “human supply chain”—whose operation undermines the rule of law in the workplace, benefitting U.S. companies by reducing labor costs while creating distributional harms for U.S. workers, and placing temporary migrant workers in situations of severe subordination. It identifies the human supply chain as a key structure of the global economy, a close analog to the more familiar product supply chains through which U.S. companies manufacture products abroad. The Article highlights a stark governance deficit with regard to human supply chains, analyzing the causes and harmful effects of an effectively unregulated world market for human labor.

That’s the stuff to give the troops! And here is a worked example, from page 472 et seq. I apologize for the length, but it’s lovely because all of the links in the chain are displayed:

B. WHERE HUMAN AND PRODUCT SUPPLY CHAINS MEET: AN EXAMPLE

B. WHERE HUMAN AND PRODUCT SUPPLY CHAINS MEET: AN EXAMPLE

Apple Fresh is a (fictitious) apple cider maker in Washington State…. Like all employers, Apple Fresh is responsible for ensuring that its employees’ wages, benefits, and working conditions comport with legal and contractual minimums. It must also pay social-security premiums on its employees’ behalf and cover their unemployment and workers’ compensation insurance. … As part of its effort to meet those demands, Apple Fresh decides to outsource its apple pressing to one of several food processors in the market, Presser Inc., which can produce the cider more cheaply and efficiently. Once it signs a contract with Presser, Apple Fresh is released from responsibility for the social insurance and many of the working conditions of the workers who press its apples, because it is no longer their employer. Presser now bears those obligations. …

In year two of the contract, Presser decides to try to decrease turnover and increase its profit margin by using temporary migrant workers to staff its plant. Its owner had been contacted not long before by the U.S. agent of a labor-recruitment firm in Mexico City…

Oooh, lookie. Rent-seeking intermediaries!

… to discuss the advantages of contracting the firm to hire H-2B migrants, including lower costs and a steady supply of uncomplaining workers. Presser’s human-resources department calls the agent and asks him to begin the recruitment process. The agent in turn contacts the firm in Mexico City, which has sub-agents in a Mexican state capital, who work with brokers in rural areas to sign up would-be migrants. As the migrants travel up this chain, each of the agents demands a side payment from them, on top of the cost of the visa and travel expenses. By the time the workers arrive at Presser’s plant, they owe high-interest lenders over three months’ salary to pay back the loans they took out to cover the charges. These fees are all in violation of Mexican law, but none of Presser’s recruiters has been penalized, both because the law is rarely enforced, and because the principal recruitment firm blames “unauthorized individuals” for the violations.

The migrants are well aware that to make good on their loans and begin to earn the money that their families back home are expecting they must not displease their supervisors at Presser. If the migrant workers do complain, and are fired, they are immediately subject to deportation, because their visas are valid exclusively to work for Presser. In that sense, Presser can rely on U.S. government enforcement of immigration law as an additional mechanism of control over its labor force, whether it or the recruiter makes the call to the government….

When the law releases Presser from liability for the actions of labor recruiters that provide it with indebted workers, liability that Presser would have borne if it recruited the workers directly, it allows Presser—and Apple Fresh and the retailers that purchase its cider—to shed costs and (potentially) increase profits without paying the price for the means through which these benefits come to them. Their lack of responsibility is a legal fiction. In fact, both Presser and Apple Fresh have actively chosen to subcontract aspects of their business because the combination of private contracting arrangements and public laws about immigration control and liability for the treatment of migrants and workers allows them to benefit from the decision to outsource a firm function without bearing the true cost. Neither, however, is likely to benefit much from this decision, beyond the ability to stay in business…. The degree to which Presser and other actors profit depends on how much cost pressure there is from above them in the supply chain. If the top firm in the supply chain is demanding much lower prices from them, the move to using temporary migrant labor may just allow them to stay afloat.

“[T]he top firm in the supply chain….” Hell-o-o-o-o, Walmart! Hell-o-o-o-o, Amazon!

Quod erat demonstrandum, labor migration as a human supply chain. Gordon has policy recommendations[6], as well, and perhaps we’ll look at them at a later date.

NOTES

[1] In the famous Zong massacre, the “cargo” was thrown overboard for the insurance money (back in London or Liverpool, because yes, there is always a financial angle). Note the fetters in J. M. W. Turner’s The Slave Ship:

I wonder if “packages” are insured as well. A topic for further research!

[2] Of course, human trafficking is bad, and 20.9 million people (estimated) should not be subjected to it. Ditto “family separation.” But to focus only on “victims” is a lot like focusing on how to save “poster child animals” like the polar bear, synecdoche that erases the presence and action of the larger, changing climate system of which the polar bears are only a part. And that system needs to be changed, whether the polar bears are saved or not! Sure, sometimes the poster animals (or babies) are useful for fundraising, but when the institutions supported are siloed and they too erase the larger system, they can be actively destructive.

[3] This is close to the Migration Policy Institute’s estimate of 44 million.

[4] Certainly a lowball estimate. A fraction of those of working age will be professionals, a tiny fraction will be wealthy individuals investing in real estate, etc. Outweighing them will be the families of working class workers, who are themselves working class, whether they work or not.

[5] Fordham, University of Iowa Law Review… It is not uncommon for the real work to be done outside the confines of Yale and Harvard; one thinks immediately of the University of Missouri at Kansas City, the epicenter for MMT. But do look at Gordon’s CV; it’s impressive.

[6] I bet a lot of those migrants at Apple Fresh have babies as well. What do you think?

A bit OT, but it strikes me as odd that “Puerto Rico” is listed in the Pew Research table as a separate country where migrants originate from. So Puerto Rico is definitely not part of the US.

I should have said “country or region.”

At some point, I need to get to the political side of Gordon’s model, because the discourse is just totally messed up on all sides, including the AbolishICE side. Hoo boy.

Fascinating read. I would appreciate even more detail on one of your notes re the assumption that 75% of 50 million are working class? Why 75%? Hope you’ll continue expounding on the “labor-migration-as-human-supply-chain” topic soon.

“And here are the countries our migrants come from, as of 2017. From Pew Research:”

5th on that list is Puerto Rico. Perhaps I’m misinformed (wouldn’t be the 1st time) but I thought Puerto Ricans were U.S. citizens.

How does the human supply chain described in the fictional case not qualify as indenture servitude?

err.. that’s indentured servitude.

(No edit function today?)

It so does seem to be an obvious mistake.

But then again this new counting method will allow us here in AZ to count all of those Californians and Texans showing up here for work as immigrants and throw them out. Or we could return AZ to Mexico – another of my favorite topics.

My real point in giving that table was to point out the Mexican stock vs. the Central American flow, the occasion of the current “migrant justice” moral panic.

If the importing of migrant labor (H1-B Visa and H1-A) was made illegal in the US then wouldn’t that solve the stagnant wage issue that we have at the bottom of society? That would certainly create a labor shortage in that market and wages would inevitably increase dramatically for that work. If the wages increase dramatically then that would the people that work in that market would increase demand by purchasing more products and services and in turn that creates more jobs in other industries. Didn’t something similar happen in the 30’s-50’s when immigration was dramatically reduced and this helped contribute to a labor shortage?

I don’t think so. Gordon points out that the middlemen are arranging for visas.

Maybe those visas should be severely reduced? No country has all the required specialized help needed, but it seems that most of those visas are being used to replace Americans already doing the work. Reduce the visas and reduce the unemployment.

Great article. I’m interested in the “trade” in highly skilled professional workers which might be a bit off topic, but here goes. Developing nation to developed nation professional migration and what drives it. Our late and not so great BC “Liberal” government, really a very right wing party, had a few years ago estimated that there would be a 30 some % shortfall in skilled therapists in the future to deal with the aging population and population increases. Yet they were at the same time cutting funded therapy seats at BC universities. Gotta balance that budget and the BC Libs were otherwise awful on education. So, where would the needed therapists come from? The understanding was, well, immigration and migration from less desirable Canadian provinces. Also, therapists and other health care professionals from many developing countries are very well trained and often seen as more “compassionate” than North Americans with a high work ethic. So there you go, a neo liberal government, in order to balance the budget, cuts education spending and combs the world for skilled migrant labour, including say, Atlantic Canada. This is a big economic drain for developing countries when you count up all the financial plus social resources you must invest in educating a child from birth through post grad degree. Skilled labour migration is fine, but I have to question the use of it to facilitate budget cutting. Question: you read that 20 plus % of NHS workers in Britain are foreign born. Why so high? Aren’t native born children being educated in the professions? Too much Tony Blair and the Tories for too long? I’m just wondering out loud. Lastly on this, the joke has been made that Trump will be good for Canada’s educated migrant supply chain, I mean, think of all those American nurses who might be willing to come north to occupy positions in “hard to fill” areas which is most of BC outside the Vancouver area in order to get away from Trump. Like the plains Indians of the 19th Century, escaping to the Land of the Grandmother. But you have to be careful about what you say here. Canadians generally don’t understand sarcastic humour and are uncomfortable in reacting to it. It’s a cultural thing or something.

On a further note, I guess the economic demand for educated professionals by developed countries at the expense of underdeveloped countries is an old one. Read recently that the main motive for the Vikings to raid monasteries was to capture literate young men and boys and then sell them off for a large profit to the Byzantines and Islamic countries because that’s were the money was and educated slaves were in high demand. Literate people were the professionals of the age. Can you imagine the resources it took to educate someone in a monestary in 950 CE compared to available wealth? The Byzantines and the Islamic countries certainly had the wealth to educate their own slaves and they did so, but I suppose it was cheaper just to pay off the Vikings for an equally good but cheaper product. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Of course the view of labor as a commodity is hardly something new that can be blamed solely on neoliberals. As the above points out Southerners did it with slaves and non Southerners did it with the Chinese building the trans continental railway, the middle Europeans working the meat packing plants in Sinclair’s The Jungle, the Irish in the Pennsylvania coal mines etc. Historically this big empty (except for those pesky native Americans) continent was always considered to have a labor shortage. Some would claim that it still does or at least a shortage of those willing to work the worst jobs like poultry plants. It’s hard to draw the line between actual need and exploitation….probably it’s always some of both.

If one really wants to bring back the working class then what is obviously required is a return of skilled labor jobs and not the unskilled variety represented by Walmart. Some of these skilled jobs–construction–are going to immigrants but mostly they have probably been off shored. Saving the deplorables will take more than just building a wall.

Excellent analysis. I use to commiserate with my fellow wage slaves on our fates sometimes, but we were not in situations of truly “severe subordination.” Many (all) could have told the management off or complained to the right state agency and easily gotten work elsewhere until the Great Recession.

The triangle trade was unregulated and the merchandise was considered less than truly human by Europeans. Initially most of the slaves in the sugar plantations were worked to death which meant more had to imported. The United States was unusual in that the birth rate always exceeded the death rate. Thinking of the large numbers who died in the Middle Passage reminds me of the large numbers who die every year in the deserts and mountains between Mexico and the United States, or before on the buses and roads after they get off the Death Train.

Working people to death while ignoring what laws they can’t change and importing when possible cheap and effectively enslaved workers. That’s how American businesses are increasing their already huge profits. Crapification of everything just makes everything crap. But then the management can sell the dried excrement as fertilizer and fuel! For more profit.

Supply chain?

So I guess businesses can now have a Human Commodities Department

instead of a Human Resources Department?

Great Topic, thanks.

I particularly liked the phrase

“Transnational migration is a market, of course”

It could become one of those meme templates (snow-somethings?) for exposing and mocking virtually any neoliberal position:

e.g.

Education/Healthcare is a market, of course

or

Science is a market, of course

or even

A good pale ale is a market, of course

Clearly it may take a while for the usual suspects to realize they’re being mocked, rather than stumbling across a potential new disciple with incisive insights.

Incarceration is a market. Maybe also functioning as a supply depot for a prison labor market?

Similarly, maybe the detention “shelter market” for separated babies and young children, and unaccompanied minors will feed the adoption market, or the child labor market.

Or, marym, darker yet, the market for young organs, as yet untainted by drugs or alcohol. I have obviously been reading too many dystopian novel.

Obviously I’ve been reading too few, as I didn’t think of that.

Here’s another aspect of prisons as jobs creators; and dividing-and-conquering:

Because surely “this remote Texas town” has no need for government programs that would create jobs to provide better healthcare facilities, schools, roads, internet…

The one thing that cannot be allowed is a – Labour Market – in the Free Market [tm]….

One thing that won’t work … one world government. If you get rid of all boundaries, then all cross-boundary problems disappear like magic. Except that then you have converted all cross-border human trafficking to internal human trafficking. And we don’t have any of that, do we? Only 20,000 teen-age girls.

People are what people do. When people do evil, they are evil.

Thanks, Lambert, for your profoundly disturbing post. And for the link to the Gordon study. A worldwide human supply chain; interchangeable, disposable widget bodies being loaded, transported, shunted to work locations, fed into the machine, disposed of when their production levels fall .. like chickens with declining egg production. Combine this with our mass incarceration system … 2 million working age males (mostly) caged up … and you have … what … a draconian system of population control working in the semi-legal shadows. And a small group of predators making their fortunes off the trade. It’s just after 8 am, but I need a stiff drink.

As well as those caged men and women being used as slave labor in manufacturing

It is also happening with the immigrants as they “voluntarily” clean, cook, and do maintenance or they do solitary, beatings and transfers to more desolate prisons, or other punishments else deviously evil thoughts can think of. They are supposed to get paid also, but frequently are not or the pay is shorted. One would think the dollar a day is low enough but I guess not. Completely unconstitutional of course, but who cares about the law, or justice, money is the thing. Just profit.

For one thing the problem is Who is Labor Working for? What we wanted in America was a Free Country where if you didn’t have a job you could get one from your employer’s competitor, or go to another state.

“I was looking for a job when I found this one.” was the phrase of the roughnecks on the oil fields.

“My past is your future.” is what I said when asked what I thought of the Mexicans cleaning the seats in the Coliseum. I was working there not just because I had skills that were adaptable to the job, but because I had a Union Card.

The reality of how labor is to gain mobility has long been understood to be Unionization.

The agents who charge their labor too much for access to a position are essentially corrupt. An IATSE Local charged me 3 percent of my pay for its administrative work. Better deal then aye?

When the talent is rare as in the case of actors it is the Guild. SAG-AFTRA is amazing.

Show business is a mature business. Entertainment is desirable, necessary and happens just about everywhere. Entertainment and the Arts, I think that is even often one section of the paper, magazine.

Unionization in Show Business is more advanced than even unionization in aviation. Aviation is a younger industry. More often in Aviation it is only the pilots and the mechanics may be unionized whereas machinations have forestalled ground services aviation unionization.

If things are not done professionally in Aviation people can be killed.

If things are not done professionally on sets and stages people may well die. Deaths from theater fires are way down since the institution of the Fire Curtain. Even though limelights don’t set the place on fire, you still have curtains being set alight by hot lights or pyrotechnics from time to time. You are much less likely to be burned to death or crushed when the show is put together and run by IATSE than when put on by “Independents”.

I could go on with what I know from the trajectory of my life as labor with two primary “Careers”. I worked in Aviation Ground Services and Motion Pictures & television. My point is that within the seeds of how labor is organized in those two industries are solutions to the conflict between employing entities whose motives are more singular in benefits, and union labor that more often shares in the benefits of their contribution to the producer’s wealth.

At one point, when I was young and strong, I recognized that I was able to go almost anywhere in the country and get put on a job because I had my union card.

Sara Horowitiz, founder of the “Freelancers Union” is on the right track.

Sara Horowitiz is a MacArthur Grant winner.