CalPERS seems determined to embarrass itself in public.

At its summer retreat next week, the CalPERS Board will receive a presentation called Digital & Innovation in Engineering and Construction“Rethinking the Core Economy”(sic). It is part of a a panel on “Rethinking the Core Economy” and will be presented by a McKinsey Associate Partner, James Nowicke. We’ve embedded the document at the end of this post.1

The fact that the title doesn’t make sense and comes off a typo is par for the shoddy quality of this piece, which nevertheless is an official McKinsey work product.

We solicited the input of readers who have extensive experience in the construction industry or are academics with construction as a focus of their research. We received an overwhelming response.2 All fourteen experts gave critical assessments, with most being derisive, particularly in light of McKinsey’s aggressive opening claim, “We believe that a 20-45% reduction in the cost of major development projects is possible through emerging innovations.”

All you need to know to judge the reasonableness of this claim is that 40-50% of building project cost is labor. Raw materials are typically 40-50% of the total (some sources allowed for contractor profit margins in their estimates, others didn’t).

So McKinsey is suggesting you can not only eliminate most if not all labor costs, but that those savings would not be eaten up by greater managerial overheads (really, a transfer from one source of labor to another) or the costs of the newfangled technologies (licenses, hiring new types of consultants, and/or paying up for newfangled materials). Not only was this 25-45% assertion never substantiated, yet by page 8 had been inflated to “up to ~45%”!

And to the extent that there is anything that could be depicted as supporting that claim, it’s a slide on page 4 which has a grotesque computation error as well as being invalid in other respects. As reader DJ pointed out:

Slide 4: each productivity bar must be multiplied by fraction of project total – e.g. 10% Design and Engineering but D and E might be 10% of total project cost so for total impact 10% of 10% is 1% of total. Similar for all bars!!!! So total way over estimates total impact.

Some reactions, all from people with decades of experience in construction in managerial roles, such as an architect turned consultant specializing in lean technology:

I was expecting a document from the famed McKinsey would actually have at least a whiff of substance, but these slides can only be called a nothing-burger. Except, that would be an insult to nothing-burgers.

Pretty typical from what I’ve seen from consultants, a lot of coded anti-labor language mixed with degrees from schools that are impressive but not really contributors to the fields of… like, building things.

This McKinsey ‘presentation’ is such a Target Rich Environment that there was a ‘wealth of poverties’ to choose from. If CalPERS falls for this, they are either terminally corrupt or intellectually incompetent, or both.

This is a dream-in colour paper, a basic sketch of hopes and possibles but yet improbable due to various countervailing constraints against technology pressure.

We’ll give a detailed critique of the presentation later, but our experts repeatedly criticized it for:

Depicting specific technologies as on the verge of adoption when most were old hat and widely used

Depicting other technologies as having great potential when they’d either been relegated to limited use and/or were unlikely to reach the performance standard indicated any time soon, if ever3

Touting figures that were unverifiable and wildly outside what seasoned professionals saw as credible

But first we’ll turn to what this document reveals about CalPERS.

What This Technology Handwave Masquerading as Insight Says About CalPERS

The fact that CalPERS, which has both an infrastructure and a real estate investing unit, would allow this document to be served up to the board reflects poorly on either their technical competence or their integrity.

But even more bizarre, the fact that staff served up this presentation as part of a “core economy” presentation, an area that CalPERS has targeted as part of its private equity outsourcing scheme, when it undermines the idea of investing in that area, makes the staff yet again look like the gang that can’t shoot straight.

Let’s start with the most glaring problem with this McKinsey palaver:

Even if this presentation were accurate, it is irrelevant to the board. Why is staff so openly disrespectful of how precious board meeting time is? CalPERS only meets 11 times a year for two and a half days each session, with nine days over the course of a year dedicated to the oversight of the health insurance program. This presentation does not purport to assist CalPERS in any way in making better investment decisions. So what is is supposed to do? Is it entertainment? To flatter board member egos by having a McKinsey partner give a “wonders of technology” talk?

If the staff were actually interested in educating the board, this is a lousy way to go about doing it. The board has asked for more training in private equity after CalPERS held a workshop in November 2015. Staff ignored their request. More generally, other pension systems, like the Dutch public pension fund, recognize that most of their board, which like CalPERS consists in large measure of union members and officials who have no investment background, need training and they provide it in an organized manner.

But CalPERS staff wants to keep the board ignorant, since non-finance-literate board members would presumably hesitate to ask even commonsensical questions or otherwise push back against staff out of fear of looking foolish in public. We saw how important it was for staff to keep the board cowed when former board member JJ Jelincic asked what ought to have been simple questions about CalPERS private equity investments. Staff members regularly stumbled over themselves, giving bad information, revealing their own ignorance, and/or resorting to lame brush-offs. More than once Henry Jones had to come to staff’s rescue by cutting off questions.

But even worse, this presentation reveals that staff holds the board in contempt:

If you believed this document, you would not invest in companies in this area of the “core economy”. The big message is “massive disruption is coming”! A 25% to 45% reduction in costs implies huge margin losses and lots of business failures.

If you were to try to make any plays related to the supposedly huge coming implementation of tech in construction, it would be in venture capital, another area CalPERS has rejected. CalPERS wants only to play in late stage venture capital, which we have pointed out will at best have risks and returns comparable to that of public companies and is really just a liquidity event for early investors who have made their money and are ready to move on.. As mature players, they would be subject to the risks of disruption by upstarts.

So does CalPERS staff assume that the board and press has so little in the way of cognitive ability and memory that they’ll try to assert in a few weeks that McKinsey supports the CalPERS “core economy” scheme, when this presentation in no way, shape or form addresses that, and as described above, actually undermines it?

Or does the staff regard these offsites as exercises in board baby siting rather than education, so as long as they can get credible-looking people?. After all, it really doesn’t matter what happens at these offsites, save upon those occasions when staff is pushing an agenda.

Why the “Technology Is Coming!” Presentation Is Fundamentally Off Base

I received so many insightful comments from readers on the McKinsey document that I could easily have written 10,000 words on it, so forgive me for having space constraints that prevent me from taking full advantage of all the material. And in fairness, some readers did identify parts of the presentation they flagged as valid.

Aside from the fact that a quick reading by many people who’ve actually been on construction sites led them universally to give it bad grades, other reference points confirm how superficial and misleading the McKinsey document is. One is a vastly more nuanced and informative article, America’s Political Economy: The Inefficiency of Construction and the Politics of Infrastructure, by Adam Tooze. A second is a paper presented at the Engineering Project Organization Conference earlier this year which looks at “Has building really changed organically, structurally and/or process-wise in North America over the last generation?” and examines in depth how forecasts for the evolution of the construction industry, and in particular, the use and impact of technology, panned out. We’ve embedded that paper at the end of the post.

There are significant conceptual and informational failings with McKinsey piece, starting with:

Lumping wildly disparate industries together and then making sweeping generalizations that are obviously incorrect. Just because industries move dirt and build things does not mean they can be thrown in the same bucket, any more than someone would do a study that combined payday lending and corporate bond issuance because they were both forms of credit issuance.

Specifically, as it makes clear on the first page, Nowicke asserts that magical cost reductions can be achieved “across asset classes, e.g., energy, infrastructure, real estate.”

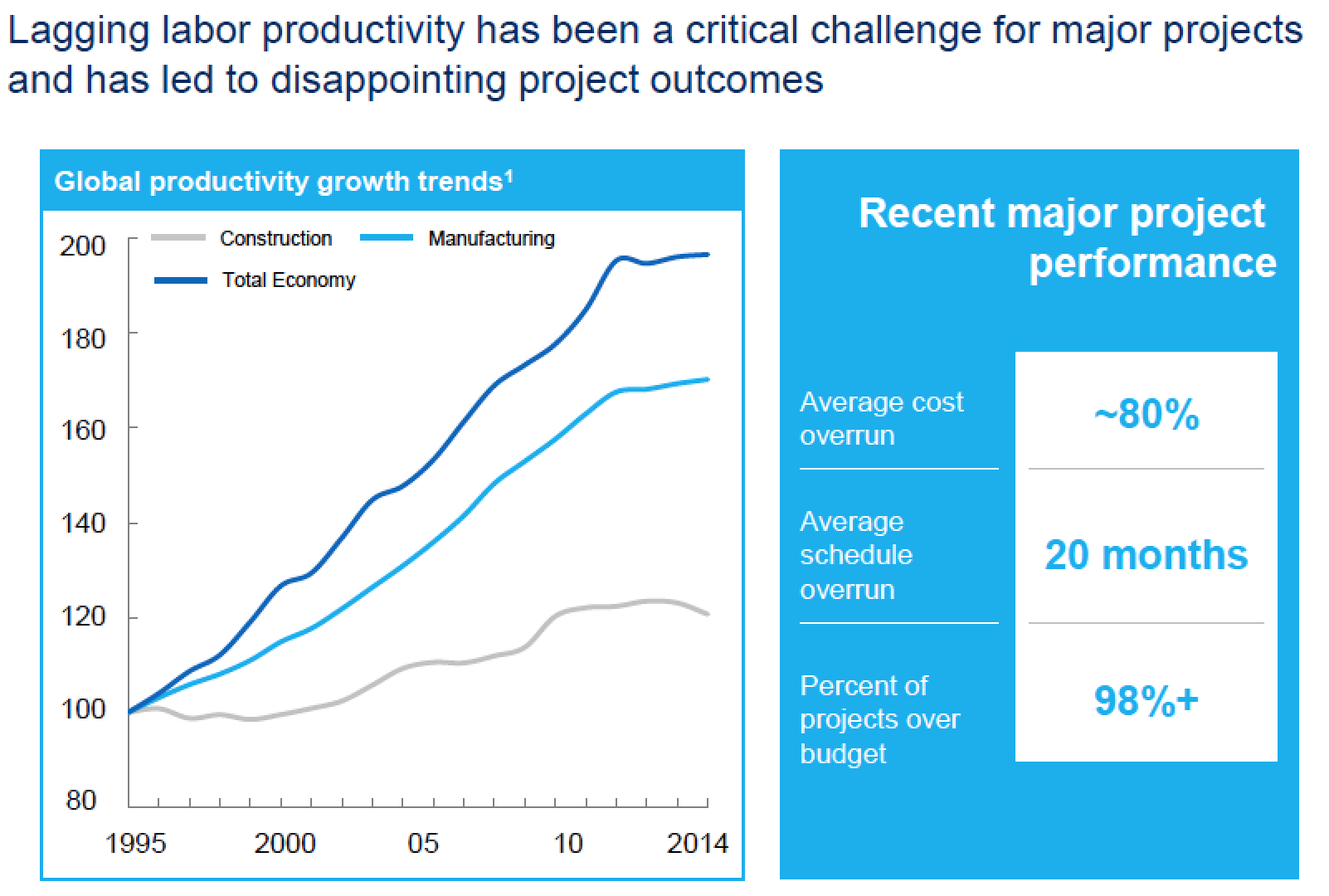

In fact, real estate development, including projects led by governments, such as public buildings, are far and away the largest segment in terms of total dollars. On the second page of his document, Nowicke presents a factoid that is bogus:

Notice that nowhere in the document does McKinsey deign to define what a “major project” amounts to. Nor does it indicate what proportion of total activity in all of its various “asset classes” those “major projects” represent.

Notice how the chart on the left has a footnote and sources, and the right half has none? In my day, we called that sort of thing “McKinsey intuition”.4

And that intuition is wrong. Readers piled on that page. In commercial real estate development, a builder who comes in as little as 5% over budget won’t get business from that client again, ever. Do it regularly and you are out of business.

And as far as Nowicke’s assertion that massively late projects are the norm, reader JH points out, ” Most construction contracts have monetary penalties that the general contractor must pay if the project is not finished on time.” The prospect of execution at dawn wonderfully focuses the mind…..

Failure to acknowledge that construction is non-standard and the standardizable elements have been and are being tackled, typically off the construction site. The misleading focus on productivity is a blatant effort to blame workmen in what is a working class industry for supposedly flagging productivity. But there have been great increased in productivity, but most of them do not showe up at the construction site. As JN put it:

This author’s thinking completely misses the massive automation that goes on upstream from the construction site. When I started picking up red lines at my dad’s office in the early 70s in central Texas, it wasn’t uncommon to draw the windows so the carpenter could make them in the field: you could purchase pulleys, ropes, counterweights and latches at the local hardware store for this purpose and everything else in the window a decent carpenter could fabricate on site from raw wood and sheets of glass.

Now, thermally broken windows with solar and moisture control performance reserved then for only the most sophisticated applications are available from hundreds of manufacturers all of whom run automated shops, the better the product, the more automated until you get to really high performance custom items where, even there, the shops making them are unimaginably high tech by any previous era’s standard.

The table on #5 would make sense if the line labeled CONSTRUCTION were labeled FINAL ASSEMBLY AT SITE, but so doing would open the window to a review of tech in construction upstream from there.

What is defined as “CONSTRUCTION” here is the final assembly on site which, because every site is someplace else and has the unique logistical, labor, regulatory, environmental etc. constraints that come with wherever it is, is not easily subject to regularization, the necessary prerequisite to “automation”. Like Lambert’s common refrain about IT, if your algo isn’t giving outputs you like, don’t fix the algo, change the inputs, the ideas in this deck could only increase efficiency in “construction” by limiting what is built to the repetitive things to which automation is easily applied.

And Adam Tooze explains why the things done at the final assembly stage are hard to make more efficient:

The reasons why productivity in construction has been less dynamic than in manufacturing as a whole are not too hard to fathom. As Daniel Gross comments, the construction labour and production process is inherently resistant to dramatic automation. It is “difficult to gain economies of scale — or to automate processes — when every job, or close to every job, is unique. If every T-shirt were made to order — different sizes, styles, cuts, fabric — it would be very hard to get a $3 T-shirt.” The sheer, overwhelming amount of choice in complex construction projects creates “huge variation from project to project, and within projects. In addition, there are important differences between home manufacturing and, say, car or appliance manufacturing. Factories create their own artificial environments that are conducive to the task at hand: The whole structure is designed for the optimal flow of people and materials, and these factories can run around the clock stamping out hundreds, thousands, or millions of units of the exact same product. As a result, operators can systematically experiment with and apply technology, tweaks, and improvements to make the process run more efficiently. Voila! Productivity gains!” In construction, “the manufacturer”, “often has very little control over the environment in which it operates. And so it has to operate slowly and carefully. …Because sites are typically small, construction has to take place in discrete, linear stages. … Each has to work sequentially to a large degree — so a single delay with a single trade, or poor coordination between trades, can throw the schedule off … Although some mechanized equipment is used, and although some builders are experimenting with prefabricated efforts, a significant part of the work is done on-site and with human hands.”

RP also argued that the ability to deploy whiz-bang technology fixes is constrained:

Everybody seems to be banking on ‘tech’ nowadays, the real flavour of the year. Yet, the latency of the industry to adopt those technologies is due to five other major pressure points acting as catalysts beyond technology: finance, environment, market, regulators and human resources.

Understating the degree of use of “innovative” technologies in construction now, apparently to exaggerate their future potential. MBM snorted at the claims about various technologies needing to be embraced by supposedly Luddite construction types:

5D BIM, drones, Lidar GPS location….all of these are in use. This isn’t new or cutting edge. And most contractors who use them aren’t using them to save money. They are using it to be competitive. If they do save money, it’s going to fatten their profits, and won’t benefit investors.

The page 7 idea, of “Lidar as built verification”? Old hat too. Virtually all clients see it as too pricey to be worth using.

GI has more curt words:

Lean is a planning methodology, like Six Sigma but for project planning, lots of post-it notes involved. It’s not whatever this slide thinks it is. Also every aspect of supply chain of construction management that can be digitized IS already, there’s a huge industry around it. Scheduling software like Primavera P6 or even general project stuff like Project, SAP databases and custom modules and a whole other class of consultants, computerized inventory management, on and on and on, none of it’s manual.

Reader SB, a lean construction expert, disagreed vehemently with the assertion on page 6 that software enabled lean construction:

We have had a lot of success in reducing costs, schedule delays, and accidents, but definitely not through the use of technology. We urge people to skip the technology and start having the conversations between specialists with sticky notes only. (BTW, asking for more technology when your team is badly behind is kind of a joke in Lean circles, where Toyota is famous for adopting technology after everyone else…..)

Another bizarre hype was the slide on page 4, which attempted to take survey data, which is already questionable unless the survey instrument has been well tested, and attempt to convert them into somethings with the false appearance of rigor.5

Overhyping the potential of technologies not yet in wide use. The presentation showed images of robots laying bricks, when their status is similar to that of Flippy the burger flipping robot, who was quickly retired because he wasn’t fast enough. The limitation of bricklaying robots is that they need nice pretty well prepped sites on which to work, and the limited conditions under which they function well means they are also a way away from meaningful commercial use.

Similarly, the presentation also hyped 3D printing. CL gave a dose of reality:

Given the context of greenhouse gas mitigation, our construction standards are entirely obsolete here in North America…and that is the context that future commercial construction will also have to accommodate. Much of the hype around technology in the building industry has no real use in the construction of high performance wall assemblies. These assemblies are quite sophisticated ‘sandwich’ style walls that require special membranes. At best, my own company uses Autocad technology to prepare the world and we build these structures in panels and the stack them flat before they get erected on site. This process requires alot of conscientious labour and would be likely impossible to execute with robots. As for 3D printing, simply building a structure out of concrete with little insulation will have no relevance in a future of decarbonization.

GI was less polite:

3D printing: This is a joke. There’s a whole trade of people who make custom parts from metal – machinists. 3D printing isn’t a realistic option for manufacturers or builders of any kind, the materials you have access to aren’t useful, the quality is low, and it requires difficult technical training.

DJ flagged “precision validation” as irrelevant:

Precision Validation – bogus – project components not built to such mm precision – think of parts of a car fitting together versus lines etched onto silicon chips – several orders of magnitude different. So validation to mm makes no sense.

And VE pointed out that robots use would be largely limited to the very final stages of construction:

This is Musk-level handwave. He tried it with automation of assembly lines, as an expensive confirmation experiment of what the industry already knew. Maybe he can do this with his Boring Company for McKinsey?

Robots on building sites? The author must have never visited one. They make robot competitions to navigate much less haphazard places than building sites. Building sites are also far from very-clean assembly lines. The only other place I can think of being more dirty are mines. So expect more expensive robots, with more expensive maintenance.

VE also pointed out that on page 8, Nowicke greatly exaggerated the importance of “rework” as an issue as well as the ability of “innovation” to solve it:

Rework – most of the rework comes from two sources. For new buildings, it’s the investor changing their minds, or newly discovered facts like the site geology being wrong (or the information just plainly ignored). Real human-error still happens, but it’s mostly as a result of miscommunication. We can as well miscommunicate via newly fashioned tools than with face to face meeting (and arguably more). Oh, there’s a third source, which is intentionally shoddy work that gets discovered by the investor and is camouflaged as a human error….

My contacts say at most 1% of rework due to human error during the actual construction (assuming reasonably diligent builder/technical oversight). The industry spent centuries on trying to minimise rework-due-to-error, and got pretty good at it.

In other words, if there is a real rework problem, it’s due to cheating, and technology won’t solve for human nature.

I could go on, since there are even more conceptual and factual errors, like suggesting that construction labor could by made cheaper through Uber-like sourcing, when as DS pointed out, “Much construction is way more sophisticated than driving a stranger to the airport on one’s slack time” or as JK points out, “some slippage in the presentation between the idea of “labor productivity” and “productivity” in general (slide 3 vs. slide 4, slide 6 vs. slide 8). This presentation is shockingly poor but McKinsey is apparently confident it can find enough rubes like CalPERS to swallow it wholesale.

______

1 McKinsey, revealing ignorance or arrogance, labels the presentation

CONFIDENTIAL AND PROPRIETARY

Any use of this information without the specific permission of McKinsey & Company is strictly prohibited

Help me. Any journalist or California government employee knows better. This document is now a public record of the State of California. The firm really needs to up its game.

2 We received comments, in many cases very detailed, from:

SB, Architect, now a consultant for “lean” methods in design and construction

DJ, Engineer with 20 years experience on design-build projects, mainly transportation infrastructure

RP, Academic in construction engineering

WB, Architect with experience on major public projects

TS, Project manager with over 20 years in real estate construction

JN, Developer with 35 years experience in commercial real estate

MB, consulting geotechnical engineer, worked on a lot of different projects (tunnels, bridges and buildings both big and small).

GI, project manager who worked in construction as a tradesperson, supervisor, planner/estimator and a manager on both the contractor and client side

VE, Commercial construction in the EU

JH, Retired architect with 45 years of practice in the US and in Middle East, with building types were ranged from commercial to a wider range of research labs

JK, Retired architect with over 25 years of experience in commercial, institutional and infrastructure architecture

CL, Owner/operator of a construction company

RW, Former framing carpenter, later superintendent of commercial and residential real estate projects

BMB, Project manager with over 30 years of experience running commercial running construction projects in the public and private sector

3 It is possible these technologies could eventually achieve the standard needed, but to tout them as able to produce productivity improvements is misleading.

4 Even if there were underlying data, it’s clearly not representative. Real estate developers and construction companies are overwhelmingly private concerns and would never make cost or development performance information available. Companies engaged in energy development would similarly keep that information confidential. So any data at best is on public infrastructure projects only. And it therefore noteworthy that McKinsey explicitly points the finger at whatever cherry-picked sample of poor outcomes they used on labor, and not on poor incentives in the contracting process that in some, perhaps many, cases led mandates to be given to builders for their political connections rather than their competence or to unrealistically low bids. And of course, another factor that will lead to cost overruns and delays is changes in design requirements after the project has been awarded.

Another possible excuse McKinsey might invoke is that on page 2, it states that “greenfield investors” need to find good partners, and it can therefore claim its grandiose cost savings claims apply only to those projects (even though it in fact made a much more sweeping statement with no caveat, and the charts about construction productivity are based on sources that don’t make that carveout). As reader JK pointed out:

Most of the productivity gains from technology will be realized in greenfield development and large scale projects. However, a huge proportion of construction is not done in greenfields and there are many downsides to focusing on greenfield development vs. building in already developed urban areas.

5 We already shellacked this chart for its grotesque computational error, but even leaving that rather large problem aside, the chart is an intellectual fraud. Charts like this are typically generated using cost data. To play on viewers’ associations with that sort of presentation with guesstimates extrapolated from survey responses where no one was providing quantitative estimates is a con.

03core-economy-mckinsey-ppt_aEPOC2018 Pouliot Katsanis

I find myself wondering about a single point here. McKinsey’s presentation. Did CalPERS actually have to pay money for this? I have read through that presentation twice and wonder at the lack of hard data. As a vehicle for demonstrating a dog-and-pony show it might do but you would need some slick talker here. But then again a chart does not information make. When a presentation starts using words like “a major presentation” in their opening lines, then would be a good time to hang onto your wallets.

I’ve heard that documents for technical presentations are written in one of three languages – technical, plain english and idiot. Three guess which was used here. Only thing is that technical documents tend to be brief and idiot documents tend to be long but this one tends to be idiot and brief at the same time. Maybe next time McKinseys could save money and just use a box of crayons for CalPERS presentations. It would be just as insulting.

Sure there has been changes in construction as mentioned. My late father used to be a master builder and when he was working did stuff like hammer nails and pore over paper blue-prints. Nowadays they use nail guns and consult blueprints & flow charts on laptops. No big deal but just a matter of refinement and better equipment. And it was not even “disruptive” and I wonder how this is meant to play out. I saw new houses being built nearby that instead of having solid concrete foundations used polystyrene foam blocks with a layer of concrete over them instead and now those same home are finding their floors being totally “disrupted”. I hope that this is not of the sort of thing that they are looking at here.

Did a quick bit of looking and found a cost breakdown for building a house in Ireland at https://www.irishtimes.com/business/construction/labour-and-materials-45-of-new-house-cost-survey-finds-1.2651912 where it showed that labour and materials was already about 45% of construction cost. Not much room for cost savings unless you are going to cut some serious corners, not that technology companies has ever worried about breaking laws. Maybe if you paid no government taxes and fees there might be savings and I would be interested to see how far that approach got them. No, I’m serious as I remember how in the US sellers stopped paying fees to local governments and started to pay into the private corporation-run Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems (MERS) instead which worked really well – not!

This whole episode is yet another one to be added to the sad pile that is CalPERS management.

Ha ha!

But it’s the truth. Having been involved in board presentations (from a staff perspective) it was certainly my experience that if the brief was to keep the board informed and educated, then adding “entertainment” into the mix was also a priority. Sadly, it seems for a lot of people getting a board position, the attraction is to burnish your resume, have a nice day out with your expenses paid, a decent lunch and a chance to hob nob with similarly likeminded people in comfortable surroundings.

Big-picture stuff, like the McKinsey presentation is a classic example of the fodder which is served up to keep up the illusion of something important and meaningful being reviewed and decided on — trappings of modernity or cutting-edge sounding topic, lots of generalisations and nothing very specific, timeframes that are in the near-ish future but safely away from being imminent, a big (~ish) cheese presentation team from a well-regarded consultant shop, nothing too complicated or overtly political, disruptive but non-threatening to the audience itself — it ticked all the boxes. A little drama. A little edginess. A smidge of excitement. A happy ending where everyone gets their just deserts.

The Hardy Boys/Nancy Drew Mysteries, for adults. In PowerPoint.

also add in: take trips to Florida in the middle of January for conferences. Presumably European directors can find an excuse to be in the Med in January too.

Yves – would a presentation like this pass, being sent to a client of CalPERS importance, in your years at MCK? And what would a client shown that told MCK then?

Thanks for asking. Most decidedly not, but not for the reasons you might suspect.

McKinsey, like law firms, does not have controls over the quality of work done in the name of directors, which are its tenured class (McKinsey uses the term “partner” which in my day was limited to shareholders of the firm, to include non-tenured shareholders, who internally were called principals, and directors, who could not be made to leave save reaching retirement age or I assume a really gross impropriety)>

However, in my day, the checks on this sort of thing included:

1. Work that was made public (as this was) that contained clearly bogus information (as in it would embarrass the firm) was grounds for a principal not making partner. We had a case like that in the New York office during my time there, where a published industry study contained fabricated data (as in anyone knowledgeable would recognize that it was impossible to obtain).

2. Word would get around the firm about really good and really bad studies. Junior people do not work for only one partner. When they get done with a study, they are assigned to one of the studies in the office that then needs staffing. And if they thought a study was intellectually dishonest, they’d gossip about it.

On top of that, the firm didn’t solicit work (it responded to inquiries, which it got via having partners publish books and articles, do pro bono work, and serve on board of not for profits), so the incentive for presenting half-baked slide shows was also lower.

That presentation is just hilariously bad – it would be quite literally laughed out of the building if it was given to a crew of real construction professionals, whether designers, builders or managers. For all the reasons that Yves has outlined, and more, it has zero relevance to the real world of construction.

One thing that should be pointed out is that in some instances, very streamlined systems are possible – usually when its kept in-house for specific purposes. Retailers like McDonalds or Aldi are very good at putting up standardised units for their own needs, they rarely allow outsiders to see their costs, but its very likely that they can build for significantly less money per square foot because of this. But even McDonalds has to work outside its own systems because of local regulatory problems, such as when they want to open units in historic urban centres.

Another issue is that for some big projects high development costs precisely arise because of the interference of consultants like McKinsey and their obsessions. Its often been questioned as to why Europe and Asia can build metro systems for far lower costs per km than is usual in the US and the UK. The primary reason is that they allow long term contracts – often extending for 15-20 years or more to senior contractors, allowing for more investment in fixed plant and permanent staff (rather than more expensive contractors). The type of short term rigid contracting promoted by management consultants is precisely why these projects cost so much in the Anglosphere.

I once worked for a very large construction management company and an insider joke there was that to admit to having an MBA, or the desire to get one, was an instant firing offence. Presentations like this from McKinsey are one reason why.

I think the LIDAR stuff is interesting to look at. Yes, it’s useful. Super useful, for specific purposes. It’s also bog-common. You pick up the phone, say ‘Id like a scan of some pipework’, a guy shows up and makes a scan. The minor cost is mostly labour of the scanner guy. It’s a lot like ordering a soil sample, say.

It’s not what silicon valley disruption is supposed to look like! No one is going bankrupt. No one is making out like a bandit. No one has to sell their soul to a software company. There are no Technology Leaders jumping to the Digital Future. It’s just a useful tool that gets used by the people who find it useful, and the world works a little better.

To get more out of it, you have to get a clean 3D model from the scanned point cloud. One that replaces a bunch of points by a labeled pipe here, a wall there, etc. This is rather labour intensive, and while useful it’s not a miracle of productivity. It’s work often sent to low-wage countries, with the ‘WTF did they do’ management problems of outsourcing. I am sure McKinsey loves that aspect.

I did a bit of Googling and found the following available for free on the McKinsey site:

https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/capital-projects-and-infrastructure/our-insights/imagining-constructions-digital-future

It seems to be the source for the presentation embedded, and looks to my untrained eye to be somewhat better quality – there is more detail on some of the claims, for example, and the sources are better referenced. Of course, as with all free reports, the “you get what you pay for” rule applies.

I guess the embedded report was intended to be a shorter form summary suitable for board presentation, but it certainly doesn’t read like an unbiased summary, and I was left with a significantly different impression from reading the longer form report (namely, that the technology pieces in the shorter one are just a small piece of the puzzle, and the claimed benefits apply only across the set of changes as a whole). Overall it has the feel of a sales pitch.

Thanks for this. I did see that Nowicke, along with two more senior partners who also looked to have never worked in the construction industry, as the moving forces behind a “technology in construction” conference last year, and should have dug further.

But even Exhibit 1 damns this presentation. It has a scatterplot of “cost overruns in the construction sector” and has data only from mining, oil and gas, and infrastructure. No real estate, when real estate is almost certainly the biggest sector in the construction industry. On top of that, the server for one of the sources for the chart, herold.com, isn’t responding, and a Google search on “herold.com,” even when filtered for a date range that looks consistent with the dates in the footnote, doesn’t come up with anything relevant-looking on the first few pages. The other source is proprietary, which of course raises questions of sample bias, particularly given McKinsey not giving any more demographic information about what projects might be included.

When I first worked at Northwest Airlines in the early 90s, I was one of a number of ex-consultants who had been hired after the 1991 LBO, and the consulting rule that “all the data in your powerpoint presentation must be footnoted” took hold. In a presentation arguing that a 4-way merger of Northwest, Continental, KLM and British Airways would produce huge profits (even though Northwest was just couple months from beginning work on a chapter 11 filing), all of the economics were driven by claimed “revenue synergies.” That section, written by an ex-Bain consultant, footnoted the critical synergy assumption with the three letters “DRE”. Three letter codes are extremely common in aviation, so no one ever asked about it. The source of the revenue synergy assumption was a Direct Rectal Extraction.

But the footnoting rule had been correctly followed.

Hilarious!

“Digital & Innovation” [adjective + noun] is a serious linguistic misdemeanor.

Why not throw an adverb into the word salad: “Digital & Innovation & Disruptively”

With buzzwords like that, a consultant can’t lose.

*checks watch to tell client what time it is*

So, why are construction costs in the U.S. higher than in many other first world countries?