By Rachel Lurie , an Analyst at the Princeton University Investment Company and Ashoka Mody, a visiting professor in international economic policy at Princeton University and previously, a deputy director at the International Monetary Fund’s research and European departments. Originally published at openDemocracy

On June 23, 2016, the British public voted by a 52-48 percent margin for the United Kingdom to leave its membership of the European Union. A popular view is that British citizens favored Brexit because they were swayed by misplaced nationalism and base xenophobia. Most academicstudies, however, find that the Brexit vote reflected economic grievances: economically distressed regions had higher “Leave” shares; and people under financial stress were more likely to vote for Brexit. Recent research shows that people who are economically marginalized and see their social standing slipping away are likely to identify themselves with nationalistic and xenophobic ideas and seek solutions for their grievances outside of the political mainstream.

Intergenerational Economic Mobility

In this article, we pinpoint the source of voter economic anxiety during Brexit: the shrinking opportunity for upward intergenerational economic mobility. Many parents who voted to leave had good reason to fear that their adverse economic conditions would also severely handicap their children. Many children were also influenced by their lack of economic opportunities. They did not vote to leave, but rather, did not vote at all, a decision that turned out to be an important cause of the Brexit outcome.

Many observers have noted that young British voters chose “Remain” more heavily than older citizens. The inference such observers draw is that if more young people had voted instead of staying home, “Remain” would have prevailed. We find that the decision by the young to abstain, just as much as the decision by older citizens to “Leave,” was an expression of political alienation driven by economic pessimism.

Our findings emphasize that lack of upward mobility is more powerful than mere inequality in inducing deep economic grievances. Wealth and status are inevitably distributed unevenly across a population. But parents and children are doubly aggrieved if economic deprivation is handed down from one generation to another. We find that income redistribution is inadequate to overcome the pessimism caused by inadequate opportunities for improving earnings prospects.

A Rust-Belt Trap on Parents, and an Urban Trap on Children

Children’s prospects for upward mobility are determined by the educational and labor market experiences bequeathed to them by their parents. Or, as Stanford University’s Raj Chetty, the preeminent scholar of intergenerational mobility, puts it, children’s success depends on the ‘opportunity’ to which they are exposed. Several studies, including one of ours, confirm that children who have higher-income and higher-professional-status parents start life with superior education and work experience (Lurie 2018).[1]Such children, unsurprisingly, succeed in climbing up the income ladder. Those who are brought up in better neighborhoods gain a further advantage.

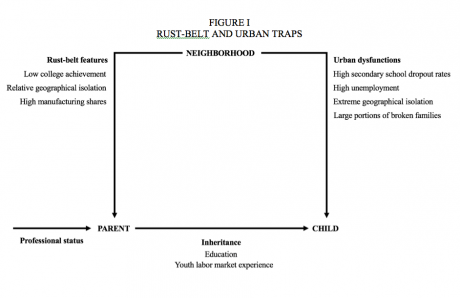

Following Lurie, we analyze the value to children of parental and neighborhood advantages. We obtained data on individual characteristics from longitudinal survey data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and the Understanding Society UK Household Longitudinal Survey (UKHLS) spanning the years 1991 to 2015 (Figure I). To study neighborhood effects, we consider several regional characteristics from the 2001 British census data. Since regional characteristics are highly correlated, we use principal components analysis to identify two distinct groupings. One of these groupings, the “rust-belt,” features low college achievement, significant geographical isolation (commuting distances of individuals in the region are relatively short), and a large share of employment in manufacturing. Rust-belt areas do not have especially high unemployment rates; rather, the high reliance on manufacturing indicates a prevalence of low-paying and insecure jobs. These are areas, in former prime minister Gordon Brown’s words, where British manufacturing, unable to face Asian competition, has “collapsed,” and industrial towns have “hollowed out,” leaving semiskilled workers “on the wrong side of globalisation”. A second grouping suffers from “urban dysfunctions” such as high secondary school dropout rates, high unemployment, extreme geographical isolation, and broken families. Such areas have limited manufacturing activity.

Parents’ incomes not only are constrained by low professional status, but also are held down if they live in dominantly rust-belt areas. And children of low-income parents tend to be inadequately educated and scarred by youth unemployment, which limits their ability to move up the income ladder. Moreover, children earn less if they live in areas of high urban dysfunctions. Thus, the most disadvantaged children are those who, having been born to rust-belt parents, have moved to live and seek work in run-down urban areas.

We find that the regional features that restrict upward mobility were influential in the vote for Brexit and in the decision to abstain.

The Vote to Leave: Rust-Belt Traps Spawn Political Protest

Rust-belt features and urban dysfunctions persisted from 2001 through 2011. Thus, on the reasonable assumption that these features persisted into 2016, people’s experiences of regional income traps had endured well over a decade by the time of the Brexit vote.

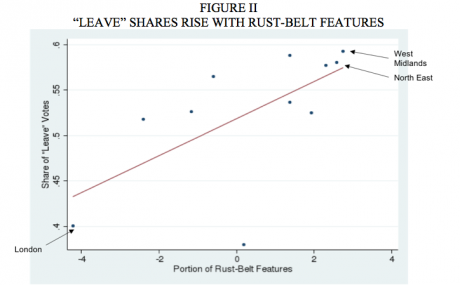

As shown in Figure II, regions with greater rust-belt features had distinctly higher shares of people voting “Leave.” Those who voted “Leave” suffered not only from their own economic anxiety but also from the fear that their children would face poor economic prospects. They attributed these woes to a hyper-globalization amplified by the European Union.

In heavily rust-belt areas such as the West Midlands and the North East, voters suffered from a deep senseof economic frustrationand regretover the loss of industrial jobs. As others have noted, the “Leave” campaign encouraged voters to blame their hardships on the European Union and on the London-based political establishment.

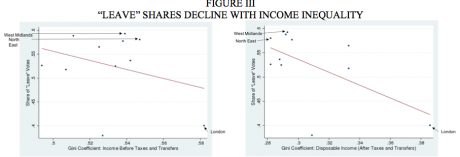

One theme of our findings is that while lack of upward mobility emphatically influenced the Brexit outcome, inequality played a more limited role in voters’ decisions. If anything, “Leave” shares were smaller in areas of high regional inequality: this is true for “market”-generated inequality and even more so for inequality after fiscal redistribution (Figure III). Thus, voters appear to have been moved not by their own relative deprivation, but rather, by the sense that even after receiving fiscal support to ease their daily lives, they could not give their children a chance of moving up in life.

Urban Traps Spawn Political Withdrawal

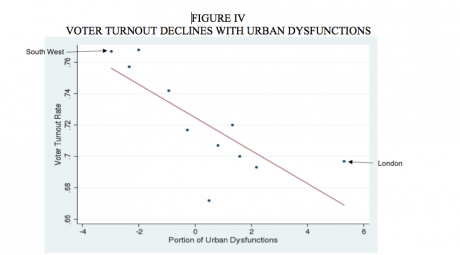

The choice not to vote was just as important in determining the Brexit outcome as the choice to vote “Leave.” Regions with higher urban dysfunctions had lower voter turnout rates (Figure IV). Thus, while rust-belt traps manifested in a desire to change the system, urban traps manifested in a withdrawal from the system.

Voterturnout data showsthat low-income youth drove low turnout rates: the lowest turnout rates nationally were among those aged 18-34, and among young people, those who were low-income voted the least. Such non-voters lived in dysfunctional urban areas, dealing with spells of unemployment and bleak prospects of making progress. For example, in Greater London, voter turnout was 79 percent in the affluent Kingston upon Thames borough, but only 65 percent in Hackney, where large pocketsof deep poverty and alienation persist. If Greater London’s turnout rate had been materially higher and its “Leave” share had stayed unchanged, the referendum result would almost certainly have been to “Remain.”

Many have portrayed the Brexit vote as reflectinga “generational divide”: the young voted to Remain while older citizens voted to Leave. But this misses the crucial significance of the non-vote. The young living and working in the financial districts of London have little in common with those living in the depressed parts of Hackney. The divide was not across generations but across those who have reason to be optimistic about their futures and those who do not. The non-vote of the young living in the grim areas of Greater London and other similar urban neighborhoods was as much a sign of hopelessness as the exit vote of older rust-belt citizens. Their decision not to vote is a warning that such political detachment could morph into more active protest in the future.

Can Fiscal Redistribution Help After All?

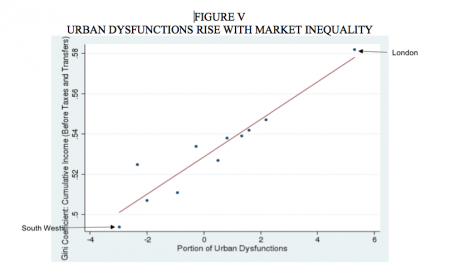

It is the case that areas of high urban dysfunctions also have high market-generated inequality (Figure V). As the London example shows, pockets of extreme poverty and social fracture continue alongside areas of extraordinary wealth. The policy question is whether more aggressive fiscal redistribution to economically depressed urban areas, although too late for the Brexit vote, can help reduce the sense of despair and political alienation in the future.

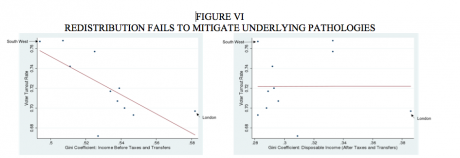

The evidence from the Brexit non-vote is not encouraging. We find that government redistribution was ineffective at alleviating the underlying sources of voter frustration. As shown in Figure VI, while higher market inequality was associated with lower regional voter turnout rates, inequality in disposable income after taxes and transfers bore no relationship to turnout rates. Accordingly, regions with lower inequality in disposable income did not have higher voter turnout. While fiscal redistribution across regions did mitigate market inequality, it did not materially alleviate voters’ sense of frustration in economically and socially left-behind areas, where presumably the government’s safety nets were not enough to significantly raise optimism about the future. Recent studies for the United States describe how as regions fall behind, catching up becomes ever harder. Those who can afford to move from the lagging regions do so. Those who stay behind are left with fewer communal resources and often lower-quality schools, a crucial factor that can limit upward mobility.

Put differently, while redistribution eases the burden of life, it does not, ipso facto, improve opportunities to increase earning potential and move up on the income ladder. Miles Corakreferences a fitting quotation from Brunori, Ferreira, and Peragine:

“[I]nequality of opportunity is the missing link between the concepts of income inequality and social mobility; if higher inequality makes intergenerational mobility more difficult, it is likely because opportunities for economic advancement are more unequally distributed among children.”

Policymakers need to aim for forms of redistribution that improve people’s life chances.

The Urgency of Creating Opportunities

Our findings suggest that improving the prospects of upward mobility must be a multi-pronged policy effort. Regenerating declining manufacturing areas will raise the incomes of those stuck in a low-income status in those communities. Parents in those regions will be able to provide more opportunities to their children. In addition, directly improving children’s prospects of upward mobility will require revitalizing poor urban areas to enhance children’s opportunities upon entering the labor market; such policy initiatives will mitigate the scarring effects of youth unemployment. Crucial also to upward mobility is the availability of quality education. Particularly, low-income families need greater access to education that prepares themfor the future.

Many have criticized the Brexit referendum as undemocratic. Accounting for those who did not vote, less than half of British citizens favored Brexit. Even those who voted for Brexit may have been manipulated by unprincipled politicians and media. Such grumbling misses the point. The referendum gave British citizens an opportunity to pointedly express their pessimism about the future in a way that is not possible in general elections, in which multiple issues and parties compete for votes. In the Brexit referendum, UK citizens were pleading through their vote – and non-vote – for a fair shot at the future. They were calling on British leaders to revitalize decaying industrial areas and bring hope to the failing urban communities in which they were trapped. That plea has unfortunately been lost amid the frenzied debateon Brexit parameters between the UK and European authorities.

The real Brexit message was only peripherally related to Britain’s relationship with the European Union. Rather, the Brexit vote signals the urgency of a task that policymakers have too long neglected: creating more opportunity and instilling a sense of fairness. Prime Minister Theresa May seemed to get it when, at her speech to the Conservative Party in October 2016, she promised “a country that works for all.” But May’s government continued the senseless fiscal austerity of previous Conservative governments. As is well-understood, austerity inflicts the greatest hurt on the most vulnerable. The task ahead is as clear as it is difficult: targeted policy solutions to raise upward mobility are crucial if Great Britain is to begin healing its economic and social divides.

[1]Lurie, Rachel. “Intergenerational Economic Mobility in Great Britain: Traps and Opportunities.” Princeton University, 2018.

This is the point that many pundits miss. In typical national British elections, if one lives in a strong majority Conservative district, it is hardly worth the effort to vote for Labour and vice versa – so many voters simply don’t bother – this is not a statement by abstention – it is instead borne from futility. In contrast, for the referendum, every vote (or abstention) mattered.

I believe that David Cameron thought that a yes vote was a done deal. Well he was not alone – almost all media and their pundits thought the same right up to the final outcome in the wee hours of the morning.

However, what was at stake in this referendum was the future of Britain, not the present, not the near term, but the long term future. As Rachel Lurie clearly concluded, the lack of upward mobility and the lack of opportunity played a significant role amongst the young voter. Upward mobility and opportunity are life progession issues; that is to say they are longer term considerations.

Amongst the older voter there were other dynamics. One dynamic is that the referendum placed the populace between a rock and a hard place. That is to say it created the binary choice of having control over one’s democratic processes or to close the door and begin the inexorable progression into the Euro and European integration. This vote was seen by many as the ‘last chance saloon’. Had the British voted yes I have no doubt that the next push would have been to join the Euro. This was a bridge too far for most of the older population. But again this is a longer term consideration.

This is the problem that the Remain camp cannot overcome. They can clearly illustrate the near term obstacles to leaving the Eurozone, but they have been unable to convince the Leavers that a better long term future can be found in Europe.

Thatcher was of the view that Europe was primarily a Franco-German construct and that it would ultimately be run by them for their benefit. If one looks at the trade figures within the EU and where the political power has been concentrated since the Euro was introduced, in hindsight it is hard now to argue with her view, especially with respect to interest rate policy, immigration policy and the sanctity of national borders.

But in fairness, there are other considerations with respect to the lack of opportunity. One is the overbearing, parasitic, financialization process that may or may not have anything to do with Europe. There are others.

In my view, the British public has lost confidence in the Prime Minister. However, she is in an impossible situation and there is currently no strong leader within any party waiting in the wings. This is the main problem facing the nation; that is, a lack of strong leadership.

Youger vote skewed heavily towards Remain. 18-24 cohort was 75%, and even 25-49 cohort over 56% remain.

It was the older vote – 65+ which heavily skewed leave, hardly the age section that has problems with current and future upwards mobility.

The EU at Thatcher’s time was Franco-German construct. But it was pretty much the UK’s problem then, and now. Then, because the UK ignored the EU (before it was the EU), so it could not shape it and there was pretty much no-one else except Germans and French to shape it. In fact, it was de Gaulle’s point to keep the UK out (once it said it didn’t want in at the start) as long as he could so that it couldn’t shape it.

The next choice the UK had to shape it was in the 90s/early 2000s, with the EU’s expansion. It had the opportunity to coalesce a block of smaller states + the UK as a counterweight to Franco/German block. Running such a block could force the German politicians to reconsider the Franco/German alliance, as the German voters aren’t much in favour of the French federalist-EU policies (which are there really just to maintain the French power in the EU).

But the UK was never interested in that alliance (which actually goes against what the UK was historically doing, wanting to keep the continent balanced).

Anyways, in my take, a non-trivial number of Leave voters didn’t vote Leave because of the EU, but because of domestic issues that were, are, and even post-Brexit will stay in the gift of the UK government. For example, the fact that the part of the GDP going to labour was dropping steadily in the last few decades (which has nothing to do with the EU).

Agree, vlade. Another thing I take issue with is the comment that saying Yes to the EU is closely connected to agreeing to be in the Euro. They are quite distinct, and wanting to be in the EU does not mean that an institution will also want to be part of the Euro system, especially since the EMU is poorly designed. The fact that not everyone clearly distinguishes the two systems is another matter.

That is incorrect, the only two non-Eurozone countries that have Euro opt outs are the UK and Denmark. All the others are not only obliged to adopt the Euro (despite misgivings) but are now increasingly pressurised so to do – it is a way to lock a country more tightly into the EU.

The real issue with the Eurozone was (and will continue to be after the UK leaves) how do you balance out the rights of non-Eurozone countries against the Eurozone majority when they are in conflict?

James, the real issue with the Eurozone has always been and still is its design, not simply the balance, though of course balance is a problem.

Whether a country can be strong-armed into adopting the Euro, which does of course happen, is not an argument either for or against whether EU and the EMU as institutions are identical. They are not. The UK became a Euro opt-out when opt-outs were allowed. The Troika were prepared to allow Greece to opt out of the Euro for a period of time but Syriza decided against it, and Italy is apparently considering it, though probably won’t do it.

I don’t think it is a question of the seven countries being strong armed into adopting the Euro – but these are after all absolute treaty obligations. None have met the stable exchange rate criterion because to do that, they would have to enter ERM II – a two-year period during which the currency is tied to the euro and floats within a range. To be in ERM II, a country has to request it, and none had. Can this go on forever?

Yes for the current non-EUR EU members. The treaty obligations are vague, and legally unenforceable – the “when they are ready” is pretty much the legal language used, and the country itself says when it’s ready.

This could be changed for _new_ EU entrants, where some timeframe on specific steps to join EUR could be added on, but can’t be done retrospectivelly for existing members. So, in theory, the UK could be hit by it _if_ the EU changed the entry conditions (which would be quite a long process) and the UK wished to re-enter. That said, those would have to be generic conditions, not UK specific ones.

> The Troika were prepared to allow Greece to opt out of the Euro for a period of time but Syriza decided against it

I never saw or heard that reported, ever. At one point there were a few grumpy statements that the Troika would be happy to see Greece exit the EU entirely — which would necessarily bring on all the economic pain and anguish of Grexit with scant assistance from the Troika. Allowing Greece to stop using the Euro temporarily was never ever on the table.

Greece failed to do any of the necessary planning for a non-catastrophic exit so they had no options. When Syriza took power they had to take the Troika’s offer or leave it. They saw exactly what “leave it” would look like when the ECB crushed Greek banks for a week.

I am sorry, but when was this offer and what was it specifically? Can you provide a link to a news report?

Your claim re Greece being allowed out of the Euro is 100% false. Do not spread disinformation on this site.

http://www.ekathimerini.com/222293/article/ekathimerini/news/schaeuble-says-temporary-grexit-idea-was-backed-by-eurogroup-majority

No. There is no visible pressure on Poland, Czech Republic or Hungary to adopt EUR. In fact, the politicians of all of those three countries can’t see adopting EUR anytime within at least two parliaments, which in political world means “never”.

There is ZERO enforcing mechanism to make anyone adopt EUR. The relevant law says clearly “when the country is ready”, and a good argument is “when 50%+ voters say ‘no’, the country is not ready”.

As in adoption EUR anytime soon would be a massive vote-losing proposition for a party in all of those three countries.

In Poland, PiS is massively popular (this might not be apparent when reading the foreign press). The reason for this is that they are perceived to be on the side of the ordinary Polish citizen and have taken concrete steps to make the lives of struggling Poles easier. One example of this is “500 plus” – a programme to pay people monthly based on the number of children they have. This makes it easier for one-income households to survive. The 500 zloties per child per month can go a long way in the rural areas and small towns, undoubtedly the core constituency of PiS.

By contrast, the opposition PO is rightly perceived as agents of foreign interests. That is why they were destroyed in the last election and are in danger of fading into irrelevance.

PiS will not adopt the Euro unless somehow forced to do so by outsiders. I don’t see that on the horizon. Any pressure Brussels puts on them can easily be countered by US pressure (PiS is a very strong supporter of NATO and Poland might be the US’s strongest ally in central Europe).

I also don’t see PiS losing the next couple of elections, as there are no strong challengers on the horizon.

The phony “advisory” poll was created (with the craven complicity of Corbyn & co.) by a gang of Tories, none of whom, NONE, has experienced “downward mobility,” neither their parliamentary cretins nor their kept press nor the sleazy financiers of their “Brexit” swindle.

Your comment expands the analysis made in this post in an interesting way. The fact that depending on where you live, your vote can be futile in general elections is skipped in most electoral analyses. Brexit vote, however functioned in the UK as a single district if I am correct. Suddenly the Tories realised that many of the votes in their districts were to leave while this might not have a close correlation with the usual Tory vote in every district. This is to argue that MPs might have quite a misguided idea of what their voters want on Brexit. Also, this is for me an additional argument favouring a single district in general elections

Interestingly enough, the AV referendum in 2011 attracted about half of Brexit vote – but could have had a much more significant impact on the UK politics (and that’s Brexit we’re talking about here!). In AV, voting for smaller parties would all of sudden make some sense, so you could (for example) put in Green/Labour/LD ordering, if you wanted (or UKIP/BNP/Tory if that would take your fancy), and your vote would be less wasted. I’d still prefer a proportional vote, but that’s unlikely to happen anytime soon in the UK short of revolution.

And I believe both the Tory and Labour elites were extremely scared of this.

Proportional voting is indeed “fairer” in the sense that voters have an second chance to influence election outcomes.

PV also increases the complexities of inter party relations ( for instance: the governing coalition have problems in Queensland with One Nation preferences not flowing back to them, as they could hope they would, given that One Nation is, like the government, “to the right”…but such is “popularism” & protest voting.

Of course the government has enough on its plate, as is: the Prime Minister just survived a (surprise) inner party election by 13 votes (48 for, 35 against (?))

Thank you and well said, especially this bit.

“This is the point that many pundits miss. In typical national British elections, if one lives in a strong majority Conservative district, it is hardly worth the effort to vote for Labour and vice versa – so many voters simply don’t bother – this is not a statement by abstention – it is instead borne from futility. In contrast, for the referendum, every vote (or abstention) mattered.”

My parents and I live in true blue Buckinghamshire, a Tory one party state and, according to my local government auditor mum, perhaps the most corrupt county in these islands. I have never voted despite being eligible for 20 years. My parents have only voted once since they arrived from Mauritius in the mid-1960s, that was to stay in the European Economic Community in the 1975 referendum.

Indeed, this is something that struck me when I moved to England – in very large areas people are deeply apolitical, not through lack of concern or interest, but just because they quite literally don’t have a choice. If you live (as so many do) in a very red or very blue constituency, there is little incentive to vote, and a surprising number of people can’t name their MP, let alone a councillor. This is almost entirely due to the electoral system in my view. In Ireland, politics is almost like a sport (some would say a blood sport), as the electoral system (Single Transferable Vote) encourages keen competition in all constituences, including between party colleagues.

Britain as a member of the EU had the best of all possible worlds. Membership in the Free Trade Zone but keeping the Pound as their national currency.

Brexit moves them to a lower economic status with much harder barriers to trade. People voting for Brexit were not voting for a brighter future.

Thank you, Yves.

Readers may also be interested in the following:

https://www.spectator.co.uk/2018/08/the-bluffocracy-how-britain-ended-up-being-run-by-eloquent-chancers/ (a timely analysis of the people who have run the UK for the past two decades)

https://www.newstatesman.com/2018/08/adam-tooze-crashed-decade-financial-crisis-review (a review by possibly the best journalist at the Guardian)

https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/media/2018/08/there-s-no-point-bbc-s-today-programme-blaming-brexit-loss-listeners (an analysis of the decline of the BBC’s flagship radio and perhaps agenda setting programme)

Unfortunately, the New Statesman, a largely Blairite rag owned by a multi-millionaire, is behind a pay wall.

I like the bluffocracy, although at least in Alex (aka Boris) Johnson I’d change it to bufooncracy.

“An ideal beach read for Ed Miliband”—Aditya Chakrabortty, New Statesman.

Great links – all 3! Thank you Colonel!

And: I had no trouble reaching the New Statesman links – NO PAYWALL, at least not when I clicked (ca. 11am MET Monday).

I do like this quote:

Thank you, PK.

Plus Epistrophy’s:

“In my view, the British public has lost confidence in the Prime Minister. However, she is in an impossible situation and there is currently no strong leader within any party waiting in the wings. This is the main problem facing the nation; that is, a lack of strong leadership.”

Two friends, like me the sons of immigrants, reckon the biggest crisis will strike when HM passes away. Us outsiders reckon she’s underrated as the glue that holds the rotting edifice together.

A friend and former classmate of one of the above works for the chairwoman of UK PLC / Inc and reckons said chairwoman and her family feel the same, too.

I suspect it will be more like the ‘indispensable’ Thai King.

Figureheads are figureheads.

I forgot to mention that, a few years ago, La Croix, the French Catholic paper, surveyed parliamentarians and showed the increasing percentage of parliamentarians who have always worked in politics. Hopefully, David, Expat and French Guy will chime in.

When I sent the link to dad yesterday, he recalled from his days in the Royal Air Force, 1966 – 91, that from the 1970s onwards bluffers began to masquerade as officers. Also, officers were not that right wing. It was the non-commissioned officers seeking commissions who were.

It’s true that in the two big traditionnal parties (PS and LR) going into politics was more and more a complete career (work your way up the organization with a fast track lane for relatives of insiders) but the 2017 election changed that a bit. A lot of the new En Marche parliamentaries are newbies and 200 out of 577 deputies in the new Assemblee had never been elected to anything. On the other hand, they are kept well way from top jobs (in government or in the party…).

CS, Varoufakis has an excellent comment on Tooze’s book on his web site — ‘CRASHED: Long version of my Observer review of Adam Tooze’s new book on the Crash of 2008’.

CS, Chakrabortty’s critical comments on Tooze’s book are better than what precedes them. It seems to me to be a critique in two halves. But the second half is a zinger. His comparison of Tooze with Hobsbaum, E P Thompson, and C Wright Wills is wholly apt in showing where Tooze falls short.

Thank you, Larry.

I have not read either review yet, but have kept them and will get the book this week.

Colonel as a Brit like yourself living in a safe Tory constituency in leafy Hertfordshire voting in a General Election for me became worthless forty years ago.

I’ve read the articles you linked to. I agree with you about Chakrabortty and this review of Tooze’s book is ( with one exception ) spot-on . The bit both leave out is the ‘ F ‘ word – fraud. The financial edifice was brought down by fraud – the sub-prime liar’s loans ( the liars being the mortgage originators not the borrowers ) packaged up to masquerade as triple A rated securities. I particularly liked Chakrabortty’s holding the knife to Osborne’s tawdry throat , but lamented his willingness to thrust it right in where it belongs .

As regards the Today programme I gave it up in favour of the balm of Radio 3 several years ago and feel much the better for it. Although when the NHS funding debacle was headline news a few months back I wrote to Sarah Sands the editor pointing out that the UK government ‘ spends and taxes ‘ and not the other way around and having failed to receive a reply wrote to the Director General which led to a reply of the ‘ you make interesting point which we will give consideration to ‘ type ( I.e. the wastepaper basket ) .

My response to all this is to make a film with my son , a professional , explaining to anyone who is interested – money , its creation and destruction without the need for technical knowledge, charts, graphs etc . The script is in its final form . The actors are soon to be cast and we will put it up on YouTube . The working title is ‘ Money for Nothing ‘ . How could it be anything else.

I reach my three score years and ten next year, came from a respectable , loving, working-class home and made my way in the world with four children and five grandchildren . I have a successful niche business which I have run for almost thirty years , but the present state of the western world is a matter of great concern and the reason I come everyday to Naked Capitalism ( keep up the good work Yves, Lambert ) . The UK is run by spivs ( aka financiers ) and has been since been for thirty plus years . I would like to see them overthrown and will do my level best to encourage a move in that direction with whatever forces can be mobilised to bring it about.

You’d have pointed to them that the money creation was reasonably well, and layman-accesibly, explained by… hold you breath… the Bank of England. Also called the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street.

That bloffocracy link, Colonel, reminded me of a few books I read a coupla years ago and today it came to me what it was. There are a whole series of humorous books who’s title starts with “The Duffer’s Guide to” (check it out on Google) to enable people to bluff there way through sports and other fields of endeavour. Looks like some took the message of those books to heart.

Yes! Yes! Yes!

As was blatantly obvious to anyone but those whose whole identity (and well-paid punditry) was based on blaming xenophobic deplorables.

Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.

Ps. Although they didn’t seem to clarify fiscal redistribution, the article seemed to imply direct transfer. Re income-redistribution, may I suggest the Eisenhower model? Glass-Stegall. 90% estate taxes. All executive salaries over $1m are to be paid pre-tax rather than post-tax. Income taxed at 15% and unearned income taxed at 35%. [Not sure about the last one]. I remember America in the late-1950s, even as other countries were recovering from the economic devastation from WWII as being a far less mean and far more equal place.

Supposedly the Euro zone have a similar problem, and that is why the “PIIGS” failed. Basically, that the German economy is doing gangbusters do not help, Italy, Greece, or any of the other Euro nations.

So effectively the Euro zone needs the equivalent of a redistribution mechanism, a mechanism that one can observe in operation in USA.

Yes, this would further move EU towards being a federal USE. Something that is likely not going to sit well in a number of nations…

I’m a little dubious about this analysis as it smacks a little of seeking data to back up preconcieved ideas (which is a near universal problem with post-Brexit vote analyses). The problem is that the vote was so tight on a low turnout that any number of factors can be said to have ‘lost’ (or ‘won, depending on your perspective) the overall vote.

I’d also have a bit of an issue with the selection of the notion of ‘rust belt’ areas. This isn’t really an appropriate identification of post-industrial areas of the UK. De-industrialisation in most of the UK is nearly half a century old – the traditional metal bashing and textile regions were in severe decline by the late 1960’s, with the final death blow in the early 1980’s. The post-industrial cities have taken a wide variety of directions economically since then – some suffering huge population decline (Liverpool, Black Country, etc), others finding new roles and relatively speaking prospering (Manchester, Leeds). They have in effect had at least a generation of change since they became post-industrial. I don’t realy think lumping them all together as ‘rust belt’ is meaningful.

The correlation between geographical areas which have slipped backwards economically and a pro-Brexit vote is clear, but I think its a mistake to assume that this is necesarily an anti-EU or even an anti-open trade vote. The experience in Ireland, which as a constitutional democracy has far more of these votes, is that when voters who feel left behind tend to reflexively vote against the percieved urban elites. An example being the relatively uncontraversial 30th Amendment, which was rejected by the voters, seemingly because they decided that if politicians and the major newspapers were in favour, there must be something wrong with it. This of course, is entirely rational. Much the same process occurred with the two EU Treaty votes which were rejected by an otherwise very pro-EU electorate.

The only things we can be fairly certain about the vote is that the pro-Brexit vote was skewed towards:

1. Traditional ‘English’ heartlands, both rural and urban.

2. Older voters

3. Regions in general long term economic decline.

Anything else is I think really just speculation.

Thank you, PK.

I agree with your assessment and have a couple of things to add:

The rust belt extends beyond the north and Midlands. There was a fair bit of light manufacturing in Northamptonshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire that was decimated in the 1980s.

The rural / agricultural hinterland has suffered, too, largely due to neglect rather than the demise of agriculture.

Buckinghamshire voted out along national percentages. The northern half, further from London, tipped the vote. Tory voters, according to an activist who campaigned for remain in Buckinghamshire and his native Surrey, were more likely to vote remain. This may tie in with Buckinghamshire becoming a dormitory for London and the older voters who voted Labour and Liberal in big numbers until Thatcher, enough to elect Labour MPs in Buckingham and Labour councillors all over the county, and since then have not voted.

It was a tight vote. But, was turnout for the Brexit referendum “low”? By what standard of comparison?

Thanks, PK. I have the same misgivings. ‘Rust-belt’ is more appropriate to the US. As for polls, different polls provide different results. As I know you are aware, the ‘vote’ was not what could be called fair, as many constituent groups which undoubtedly had a view were barred from voting. Were there another vote, which is speculative, this vote would have to be more broadly based than it was in the initial referendum.

Yes, very much agree with your analysis and view of the piece on UK “rust belt”.

Polling carried out in the aftermath of the referendum indicated that some 74% of Remain voters voted the way they did because of the financial risk of leaving, which reflected the negative Remain campaign. Leave won despite, not because of, the Leave campaign which was atrocious.

For many Leave voters, it was a last chance to leave what was/is a centralised supranational entity under construction and fix its own problems. As Dr Richard North has said many times, is it any wonder that the current generation of politicians are so poor when the power to legislate in many areas has been removed from nation states? Out of the EU, the UK electorate will be far less forgiving of the shortcomings of politicians, hopefully.

‘when the power to legislate in many areas has been removed from nation states?’

The UK, as matters currently stand, still controls, with limited exceptions, its own fiscal and monetary policy, foreign policy, education, social and health policies, defence and criminal policies, devolution as well as other matters. Trade matters are covered by the EU, yes, but most other matters remain the responsibility of Westminster. And the UK has always had to input to EU discussions on trade matters via Ministers and officials.

The Blair government was noted for the sheer volume of legislation it pushed through Parliament.

I think Richard North overdoes the argument that UK politicians are useless because they do not have enough important decisions to make. IMO they are useless because the kingmakers in the newspaper industry select weaklings who will do their bidding. Until the control of the press barons over British politics is broken, little can be expected to change. Out of the EU, the electorate will be directed towards other scapegoats, though, to begin with, the EU will be blamed for not bending to the wishes of the English electorate. And the English electorate are mostly unaware how much they are manipulated because of course no one in the MSM tells them what they – the MSM – are doing.

Amen. They are not weak – they do exactly what they want, and use the EU as a convenient scapegoat.

“the Brexit vote signals the urgency of a task that policymakers have too long neglected: creating more opportunity and instilling a sense of fairness.” Isn’t this Jeremy Corbyn’s policy?

It is the traditional/worker left policy, so yes.

But most of the European left these days has turned into an academic/champagne left, starting from the 80s onwards.

This “left” has held a “good for the goose, good for the gander” mentality combined with the idea that education solves all ills (after all, it did for their leaders).

It’s worth adding that no British Prime Minister apart from Edward Heath ever showed any real enthusiasm for Europe, or tried to sell the British people even a shadow of the Monnet/Schumann thinking that was at its origin. At the time of the Maastricht negotiations, the motto was “how little can we get away with agreeing to?”, and I don’t think that changed substantially in the years that followed. Indeed, the lack of any positive British vision for Europe, and the lack of any real constructive engagement or initiative, contributed to the generally poor image of the EU in Britain, and the Brexit vote. (Not that Brussels itself was guiltless, of course).

Evidence suggests that people will vote when they think their votes will make a difference. At least since the 1960s, there were complaints that most votes in British elections were wasted, but there were at least some real differences between the parties. After Blair, many people began to argue that, even if you lived in a constituency that might change hands, it wasn’t worth voting to have the same policies implemented by a different set of faces. The Brexit vote was nationwide, and sufficiently clear (unlike the PR vote) that there was some point in turning out. It’s notoriously true that in politics the question you ask and the answer you get may not be much related to each other, and that was the case here. Europe was identified with the cosy neoliberal establishment that had presided over unemployment and decaying public services for too long. Taking PK’s categories above, traditional heartlands were angry about the declining sense of community, older people remembered the days of full employment and functioning public services, and people in regions in decline remembered better days. In some senses, therefore, Europe was collateral damage: if these (family blog) establishment politicians were so adamant about Europe, there must be something wrong with Europe.

This essay makes good points without a point. When you can’t get a job or a cost of living raise and you can’t even go fishing you drop out. There’s no social contract to hold you. The authors imply that this is simply a problem of not sufficient redistribution… it is not. It is a far, far greater problem and yes, it is indeed globalized. For starters the whole planet of politics should make it an urgent priority to designate “high productivity” a crime against the earth and everything living on it. “Mobility” to where? Instead of all this capitalist-neoliberal analysis masquerading as social information and a befuddled plea for fiscal solutions the world needs a big clean-up program for at least a century. Cleaning up after all the externalized costs for the sake of insider profits. We actually need a cause worth working for. And a recognition of the misuse and abuse of capitalism would be a good place to start. The problem is as shovel-ready as it gets.

This chimes with my worldview. Whatever the problem — and goodness knows, there’s enough of them to be getting on with — nothing that the EU is, was, says or does appears to in any way be a solution or even the basis of a solution.

Saying that certainly isn’t the same as saying the EU caused the problems in the first place.

But if the EU toils not and neither does it spin as far as demonstrably improving the lot of the working class I, like Mr. Spock, see no practical use for it.

There’s no fundamental problem with “high productivity”. There’s a fundamental problem with consumption for consumption’s sake.

Take plastic bags – it’s not only a convenience measure. Think of the world where there are no plastic bags. Your shopping has to get in what you bring in. If you forget, you can buy what you can hold.

The plastic bag is not only a convenience, saying that you don’t have to worry about carrying a bag for your shopping. It also means you can stop to shop anytime you feel like it – whether you need it or not. It also means you can buy as much as you want in one go, as you’ll be able to stuff it all into your plastic fantastic. It removes the obstacle that forced you before to consider what, and how much you’d buy. Hey, just stuff it into plastic, throw it into car, problem solved!

On the other hand, when was the last time you washed a full load of domestic laundry in hand? It was a genuinely back-breaking work, and the “high productivity” of the washing machine is really something I personally, and most people (especially women) I know, really grateful for. Of course, if your washing machine breaks down every other year, that’s a problem (a real one). But a different one from having to do it by hand.

Otherwise I mostly agree with you though :)

I keep hearing about the xenophobia and there is some truth in that but a lot was also about economical terms. For some people the most valuable inheritance they receive is their citizenship. Open borders devalues citizenship, it makes things worse for the worst off in a country.

The ‘elite’ is voting for their own personal interests (disguised as if they are voting for the good of the country – nationalism and the worship of GDP) and that is ok (?), the poor vote for their own personal interests and they are said to be uninformed, xenophobic and easily manipulated….. I suppose it is yet another version of the banker coin-toss: Heads I win, tails you lose.

‘the poor vote for their own personal interests’

But sadly they are not very good at it are they? Hence their poverty.

I agree that economic grievances caused Brexit but it looks like desperation to me. The vast array of digital sites bemoaning political inaction, the chasm between MSM/political opinion and the rest of the country, total government irresponsiveness to street marches, unwillingness of the Commons, Treasury and their constituency of great capitalists to act in the way the majority wish – these are each adequate reasons for sticking a spoke in the wheel.

Ah.. no. The leavers are the same kind of people that think Obama is Kenyan, they think the crime rate is leaping up. That the universe was created 6000yrs ago, that white people as a “race” are facing extinction. Call them the Irrationalists. They will throw their bodies into the fire to shield the myth that the white race is unique and special in a holy way.

Google “Brexit + DUP”. If North Ireland is pulled out of the EU N.I. is screwed. The only industry doing well is agribusiness, who sells almost everything it produces to the EU But Ian Paisley’s Unionists are rooting and working to “Leave”. They don’t care about economics that affect them as long as they get to raise the finger to everyone that disagrees with them. They’re fighting to prevent the customs border form being the Irish Sea, stopping NI from keeping access to it’s agri markets. They’re demanding a hard border between the countries, damn the expense, which they expect London of course, to pay for.

There’s no way to negotiate and reason with them, their positions are their’s by Dog. The Rev John Dunlop of the Irish Presbyterian Church wrote,

“We are a people who live behind spiritual, political and ecclesiastical ramparts. We behave like batsmen facing hostile fast bowling on an uneven pitch: more concerned to survive than to win the match; playing for a draw at best; always defensive; seldom taking the initiative.”…

He also said at the time of the IRA ceasefire that the unionist community was not ready, prepared or happy with the beginning peace. He believed it was psychologically prepared to endure the violence rather than engage with republicans.

Thats Brexiteers and Trumpists in a nutshell

Your assertions carry the premise that Brexit was the result of right wing nutters and racists. Here are some key excerpts from a post on the subject by Michael Hudson, hardly one who would fit into such a category, assessing the result from the perspective of the labour movement:

Opening paragraghs:

Closing paragraph:

“Take back control” is bollocks. “We”, the working population of the U.K. never had control, and we won’t after Brexit. We live in a capitalist class society with a ruling class that controls most things, albeit in an increasing incompetent and confused way with much in-fighting. Brexit doesn’t change that one bit, that is a delusion. Unfortunately probably shared by many, but a delusion none the less. The UK after Brexit will most likely be a disaster capitalists heaven.

Agreed. It was Murdoch taking back full control. Farage is just one of his creatures.

I don’t usually respond so late after, but this pisses me off.

“Your assertions carry the premise that Brexit was the result of right wing nutters and racists.”

Yes, my assertions do. That’s because when someone is allying themselves with the DUP, I am very comfortable saying that that someone is a racist right-wing nut job.

“There is another European economy that is possible.”

You sound like that those NATO nutjobs promoting limited tactical nuclear war ‘it’s reasonable to assume that the USSR will stop their invasion if we hit their armored divisions with 10 or 20 KTs, the chance that the USSR would escalate with strikes against our transportation and supply network is minimal”

My view doesn’t come from American rubbish, it comes from talking to family in Edinburgh, and in the counties Galway and Tyrone. The Irish members are farmers, if Tyrone can’t ship their agri-product to the EU, it’s a “lose the farm scenario.”

Yea, I want advise from another American economist, I thought you people had “had enough of experts”.

He and you are examples of the clueless, insipid twats who are laying the groundwork for the greatest act of Disaster Capitalism yet. You think bespoke trade agreements with the USA and China will help the UK’s working class? The aftermath will be a frightened populace willing to exchange their dignity for necessities and safety. The only good that might come of it is the N.I. prods leaving Eire and ending up in a resettlement camp Cumbria, the Scots aren’t going to let them in, not with voting rights anyway.

Insomuch that it is Finance that is all well and good with the status quo as operating to their benefit in NYC & London and Obama & Varoufakis told British voters to vote to remain and they didn’t, & Hillary lost and Brexit won and there is no hope of less than punishment for there will be no banking other than Finance Banking like Utility and Industrial Service banking are impossible to even consider and British Banking as Finance is moving to Paris and will just be fine and profitable and parasitical as they were born to be and austerity will put more pressure on society no solution will be offered and none considered and all will dry up and blow away.

Thanks.

“Did the parasites leave?”

low upward mobility is, of course, the mirror of . . .

(wait for it)

low downward mobility

If you think of the problem as no one ever losing their elite perch, despite performance deficiencies, the problem takes on a different narrative cast, though, of course, one thing is the other, by and large.