By Sandwichman. Originally published at Econospeak

In “De-growth vs a Green New Deal,” Robert Pollin relies on the same blurring of distinctions that Robert Solow employed 46 years earlier in his condemnation ofThe Limits to Growthas “bad science.” Nicholaus Georgescu-Roegen pointed out Solow’s obfuscation in the article that inspired the term “degrowth.” That historical context is vital for understanding why Pollin’s “blueprint for ecological salvation” is no advance over Solow’s.

In “Is theEnd of the World at Hand” Solow scolded the “bad science” of TheLimits to Growthreport on the grounds that its authors’ model assumed “that there are no built-in mechanisms by which approaching exhaustion [of resources] tends to turn off consumption gradually and in advance.”[1]Solow cited increases in the productivity of natural resources to illustrate the importance of the price system as the built-in mechanism of capitalism for “registering and reacting to relative scarcity.”

According to Solow, between 1950 and 1970, consumption of iron in the U.S. increased by 20 percent while the GNP roughly doubled. Consumption of manganese rose by 30 percent. Copper consumption increased by one-third, as did lead and zinc consumption. These increases represented productivity gains ranging from 2 percent per annum for copper, lead and zinc to 2.5 percent for iron. Meanwhile, productivity of bituminous coal rose by 3 percent a year during the same period.

There were, Solow conceded, some “important exceptions, and unimportant exceptions.” Among the more important ones was petroleum, “GNP per barrel of oil was about the same in 1970 as in 1951: no productivity increase there.” Nevertheless, Solow was confident that “no one can doubt that we will run out of oil… [s]ooner or later, the productivity of oil will rise out of sight, because the production and consumption of oil will eventually dwindle toward zero, but real GNP will not.”

Solow acknowledged another important exception to his productivity argument: pollution. The price system is flawed, he admitted, in its failure to charge polluters “for using the environment to carry away waste.” Thus “the waste-disposal capacity of the environment goes unpriced; and that happens because it is owned by all of us, as it should be.” Solow saw this problem as easily remediable through common sense regulation, user taxes and investment in pollution abatement.

Georescu-Roegen’s response to Solow, in the 1975 article, “Energy and Economic Myths” emphasized the distinction between growth and development:

…if we are talking about growth, strictly speaking, then the depletion of resources is inherent in the process by definition. Solow’s exposition of why he thought The Limits to Growthwas bad science relied on blurring the distinction between qualitative development and quantitative growth and counting the former as an instance of the latter. This sort of legerdemainis, of course, standard in so-called growth economics.[2]In 1979, Jacques Grinevald and Ivo Rens translated “Energy and Economic Myths” and included it with two other articles on bioeconomics in a book titled Demain La Décroissance: Entropie – Écologie – Économie.[3]The term, décroissance occurs in the translation of a section in which Georgescu-Roegen criticized what he considered “the greatest sin of the authors of The Limits” — their exclusive focus on exponential growth, which fosters the delusion that “ecological salvation lies in the stationary state.”

In opposition to that view, Georgescu-Roegen argued, “the necessary conclusion of the arguments in favor of that vision [of a stationary state]is that the most desirable state is not a stationary, but a declining one (emphasis in original).“His argument was notthat ecological salvation lies instead in a declining (or “degrowth”) economy. It was that there can be no “blueprint for the ecological salvation of the human species.” as he elaborated in the subsequent paragraph:

Undoubtedly, the current growth must cease, nay, be reversed. But anyone who believes that he can draw a blueprint for the ecological salvation of the human species does not understand the nature of evolution, or even of history — which is that of a permanent struggle in continuously novel forms, not that of a predictable, controllable physico-chemical process, such as boiling an egg or launching a rocket to the moon.

Pessimistic? Perhaps, but it is less so if one keeps in mind Georgescu-Roegen’s injunction against blurring the distinction between quantitative development and quantitative growth. There are no “built-in mechanisms,” either of the price system, of the regulatory and tax regime or of a Green New Deal that can ensure ecological salvation because the latter requires not blueprint or a formula but “permanent struggle in continuously novel forms.”

So how does Pollin’s Green New Deal stack up compared to Solow’s “built-in mechanism” of the price system? First, with regard to the distinction between qualitative development and quantitative growth, Pollin gives no indication of being aware of Georgescu-Roegen’s (and Schumpeter’s) distinction. Instead, Pollin does distinguish between “some categories of economic activity [that] should now grow massively” such as those associated with clean energy and others, such as “the fossil-fuel industry that needs to contract massively.” Charitably, this shift may be interpreted as at least tacitly acknowledging a qualitative development rather than simply a quantitative growth/contraction. But because Pollin doesn’t make that distinction explicit, his concluding comparison of “average incomes” from a degrowth scenario vs his Green New Deal is fundamentally flawed.

Decoupling the Derivative

Pollin refers to the process by which this simultaneous massive growth of clean energy and massive contraction of fossil fuel is supposed to occur as “decoupling.” Decoupling is a synonym for what Solow called natural resource productivity. The calculation is the same — national income divided by the quantity of the resource consumed or waste emitted. But decoupling, as Pollin uses it and as it is commonly used, is a deceptive term. Economic activity is not decoupledfrom the consumption of fossil fuel, as Pollin claims. It is the rate of changeof economic activity that is decoupled from the rate of change of fossil fuel consumption.

Resource productivity (or rate-of-change decoupling) is analogous to labour productivity, as Solow pointed out, and that parallel suggests a method for side-stepping the measurement complications that arise from GDP. One can instead calculate the decoupling of carbon dioxide emissions from aggregate employment. This alternative restores the original sense of productivity measurement, which was in terms of physical inputs and physical outputs rather than dollar values.[4]I will discuss the measurement complications later, in connection with incomes but first, let’s review Pollin’s optimistic account of the prospects for “absolute decoupling.”

According to Pollin, citing a blog postfrom the World Resources Institute[5], “between 2000 and 2014, twenty-one countries, including the US, Germany, the UK, Spain and Sweden, all managed to absolutely decouple GDP growth from CO2 emissions…” This did not happen. GDP growth was notdecoupled from CO2 emissions. What was “decoupled” was GDP growth from emissions growthand, more precisely, from growth in one commonly-used estimate of emissions.

Such claims need to be examined for their attention to two important subtleties: territorial emissions can be reduced by outsourcing those emissions to an offshore supplier. What about emissions embodied in trade? And GDP growth incorporates all kinds of distortions (we’ll get to those). What about a more meaningful indicator of the level of economic activity, such as total employment?

Of the twenty-one countries claimed by the WRI to have achieved “absolute decoupling” between 2000 and 2014. Slovakia, Switzerland and Ukraine had increases in their consumption-based CO2 emissions that adjust for emissions embodied in trade. Bulgaria’s consumption-based emissions were unchanged from 2000-2014. Portugal, Romania and Ukraine had declines in aggregate employment. Denmark had no increase in employment. There was no consumption-based data for Uzbekistan and its reported employment data (ILO) does not appear credible, so it can be excluded from the analysis.[6]

That leaves 13 countries with “absolute decoupling” of the rate of change of employment and the rate of change of consumption-based emissions. Of those 13, the Czech Republic had reductions in average annual hours that exceeded the increase in employment. Finland just squeaked through into absolute decoupling territory if defined by changes in aggregate working hours and consumption-based Co2 emissions.

Twelve of the 21 countries touted by WRI meet the more rigorous rates of change decoupling criteria. Again, no countries decoupled employment growth from CO2 emissions. The average gap between growth in employment and decline in emissions, weighted for the size of employed work force in 2014, was a bit less than half of the gap between GDP growth and change in territorial emissions. (17.6 percent versus 37 percent). That is 12 out of the 63 countries that had emissions of at least 12 MtC/yr in 2000, as did Bulgaria. In other words, 51 other countries among the top 63 did not have absolute decoupling of employment growth and emissions decline.

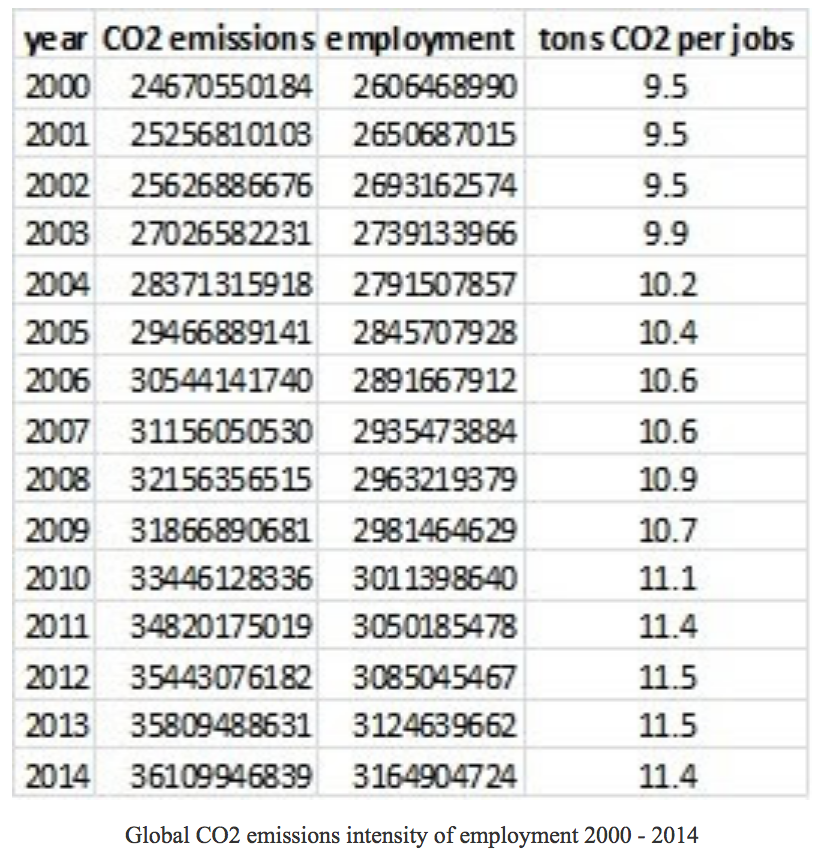

In spite of those 21 or 12 countries that “absolutely decoupled” the rates of change of GDP/employmnt and CO2 emissions between 2000 and 2014, tons of CO2 emitted globally per employment-year rose from 9.5 to 11.4. That is neither an absolute decoupling nor a relative one. That is a 20% intensificationof emissions per job, a declinein the productivity of emissions. Meanwhile, China’s increase in consumption-based carbon dioxide emissions from 2000 to 2014 was 8 times the total decrease of all 21 counties for whom WRI proclaimed “absolute decoupling” of “GDP and energy-related carbon dioxide emissions.”

On the Rebound

Pollin’s treatment of the so-called “rebound effect” is also inadequate. This phenomenon, also known as the Jevons Paradox is not a separate, add-on effect to productivity and should not be treated as such. It is an intrinsic part of the “built-in mechanism” of the price system. Again, the use of synonyms and euphemisms adds to the confusion. Just as decoupling is a synonym for productivity, the productivity of resources is another way of referring to the efficiency or economy of their use. When the use of a resource, such as a fuel, is made more economical through technological innovation, its relative cost may fall even though its absolute price may be rising. Thus increased efficiency (or productivity) may lead to increased consumption. Separating out the rebound effect from the analysis of productivity or of rate-of-change decoupling is about as plausible as separating out the butter from a baked cake.

In formulating the “paradox” of greater efficiency leading to increased consumption in 1865, W. S. Jevons described it as “principle recognised in many parallel instances,” particularly that of labour-saving machinery eventually increasing employment.[7]But fuel efficiency and labour saving machinery are not merely two “parallel instances,” they are two defining moments in a single, continuous positive feedback loop.

Pollin speculates that rebound effects from efficiency gains will be modest, at least in developed countries, but he still argues it is crucial that “all energy-efficiency gains be accompanied by complementary policies (as discussed below), including setting a price on carbon emissions to discourage fossil-fuel consumption.” I would agree with the need for regulation or taxation to discourage fossil-fuel consumption but would insist that putting a price on carbon emissions will also put a damper on the jobs that increased fuel consumption would otherwise generate. Until the link between fossil-fuel consumption and jobs is decisively broken, you can’t choose to dial down one without affecting the other. One can’t assume post-transition availability and relative prices of clean energy sources during the transition!

This point is missed in virtually every discussion of the rebound effect or Jevons Paradox. There are not two, “parallel” rebound effects, one for fuel consumption and one for employment. The rebound of employment drives the rebound of fuel consumption, which in turn drives the rebound of employment. To decouple the employment rebound from fossilfuel consumption requires the fantasy that one can substitute clean energy supplies that do not yet existfor fossil fuels that do.[8]

Comparing Average Incomes

In his criticism of Peter Victor’s Managing without Growth, Pollin argues that per capita GDP in 2035 for a degrowth scenario would “plummet” to little more than half the 2005 level, while under Pollin’s proposed clean energy investment programme, “average incomes would roughly double.” The second chapter of Darrell Huff’s 1954 classic, How to Lie with Statisticsis all about averages, so I can’t claim originality for this point: Pollin’s otiose comparison of averageincomes under the two scenarios says nothing but insinuates too much about distribution. To mix a few metaphors, a rising tide lifts all boats as the sparrows pick away at the remnants of “oats” that have “trickled down” from the horse.

There are several other egregious distortions in Pollin’s comparison of “average incomes”: leisure time doesn’t count as income and “average income” doesn’t say anything about what a person has to give up in time and effort to receive it. GDP is not some magic cake that just appears and gets doled out in equal-sized slices. As Maurice Dobb pointed out quite some time ago:

It is not aggregate earnings which are the measure of the benefit obtained by the worker, but his earnings in relation to the work he does — to his output of physical energy or his bodily wear and tear. Just as an employer is interested in his receipts compared with his outgoings, so the worker is presumably interested in what he gets compared with what he gives.[9]In comparing the projected average incomes of his clean energy investment programme and Peter Victor’s degrowth scenario, Pollin appears to have set aside his earlier solidarity with the “values and concerns of degrowth advocates” particularly regarding GDP as a measure of wellbeing:

…there is no disputing that it fails to account for the production of environmental bads, as well as consumer goods. It does not account for unpaid labor, most of which is performed by women, and GDP per capita tells us nothing about the distribution of income or wealth.

Dividing up GDP into per capita income doesn’t eliminate these problems – or others. In 1995 the Atlantic Monthly published an article that asked, “If the GDP is up, Why is America Down,” a great riff on the title of Richard Fariña’s novel, Been Down So Long, It Looks Like Up To Me.[10] That article explained a lot of what’s wrong with the economy and what’s wrong with economics:

Once you start asking ‘what’ as well as ‘how much’ — that is, about quality instead of just quantity — the premise of the national accounts as an indicator of progress begins to disintegrate, and along with it much of the conventional economic reasoning on which those accounts are based.

Questions about distribution, about quality vs. quantity of goods, the production of environmental “bads” and the disregarding of unpaid labor only skim the surface of what is wrong with the GDP. Those questions focus on the symptoms. A deeper understanding of the root causes reveals that the discrepancy between the measurement and the thing that is purported to be measured may be orders of magnitude.

Basic accounting errors of double-counting and “asymmetric entry” abound in the compilation of National Income and Product Accounts. These fundamental errors have been highlighted by Irving Fisher, Simon Kuznets, Paul Samuelson, Roefie Hueting, Angelo Antoci, Stefano Bartolini and others. These mismeasurements are not one-off discrepancies – they also establish a positive feedback loop of incentives for cumulative misallocation of resources and miscalculation of outcomes.

In his 1948 critique of the Commerce Department’s National Income and Product Accounts, Kuznets focused on the double counting of intermediate goods, especially in the form of military expenditures and government services that facilitate commercial activity.[11]Hueting identified the problem of asymmetric entering in which expenditures on remediating environmental damage adds to GDP even though no subtraction was recorded for the damage itself.[12]Antoci and Bartolini analyzed the cumulative role of negative externalities in boosting GDP growth.[13]

It is not only that GDP doesn’t distinguish between goods and bads. Systematic mismeasurement puts a premium on expanding the proportion of bads to goods.

Over a century ago, Fisher, one of the most influential American economists in the early 20th century, maintained that faulty definitions of income resulted in rampant double-counting errors. There are three compelling reasons for not ignoring Fisher’s views on income and double counting. First, Fisher is an acknowledged pioneer of national income accounting – his definitions of income need to be acknowledged, even if only to show that they are not practicable or even are defective. Second, Fisher’s critique of the ill-defined “general concepts of income” addresses precisely the “heterogeneous combination” of goods and services that is standard in the GDP. Third, the recurrent examples of double counting lend empirical support to Fisher’s claim that the improper definition of income inevitably results in such errors.

In The Nature of Capital and Income, Fisher argued that the usual definitions of income fail one or both of the tests of being both useful for scientific analysis and harmonizing with popular usage.[14]The pitfalls of those faulty definitions go largely unnoticed, making them “all the more dangerous.”

Fisher focused on two common concepts of income. The first concept, money income, is reasonably adequate for commercial affairs because the purpose of business is to make money. But making money is not the purpose of households. Part of household production takes place outside of monetary exchange and even monetary earnings have as their ultimate purpose the purchase of food, clothing, housing and the like, which constitute the household’s real income.

The second concept, pertaining to real income, is commonly defined in terms of both goods and services. Fisher criticized this concept for its eclecticism and inconsistency. The procedure treats some items — such as fuel, food and apparel – as current consumption but apportions very long-lived items such as dwellings as if they were being rented. This leaves a variety of moderately durable items such as furniture or vehicles to be treated in an ad hoc manner. Fisher concluded that “such a patchwork of arbitrarily selected elements is incapable of furnishing any consistent, reliable, and logical theory of income.”

That patchwork is where double counting comes in. Economists “have not known where to cease calling the concrete instrument income and begin calling its use income instead. In their hesitation they have in some cases ended by including both. By so doing they commit the fallacy of double counting.”

Fisher’s alternative to the goods and services concept was “to regard uniformly as income the service of a dwelling to its owner, the service of a piano and the service of food; and in the same uniform manner to exclude alike from the category of income the dwelling, the piano, and even the food.” The latter, he argued are “capital, not income.”

As logical and consistent as Fisher’s definition of income may appear in the abstract, it is hard to imagine how it could ever be implemented in national income accounts. Monetary transactions occur when items are purchased, not when they are actually consumed. Fisher’s definition would require a vast and highly subjective extension of financial record keeping. Similarly, Commerce Department economists responded to Kuznets’s critique, conceding many of his points but stressing the technical difficulty of putting an alternative into practice.

The arguments presented in defense of the goods and services concept are usually framed in terms of expediency. Such expedients have a limited shelf life, however. Typically, proponents of the monetized goods and services concept cheerfully admit its perishability, logical frailty and limited portability. “This process can never claim complete logical watertightness,” Colin Clark confessed in 1937, “but we can be satisfied that it works well enough in practice for comparisons over periods up to, say, twenty years, or for comparisons between communities whose ways of living are not too widely different.” Once the tabulations are up and running, those caveats are ignored.

If you start with an accounting system that systematically double counts some revenue items and doesn’t count others, you also have a system of perverse incentives to shift more and more effort, investment and expenditures, over time, to the double-counted items because that will project the illusion of more robust economic performance. For apostles of growth, double counting is not so much a social accounting debacle as it is a public relations triumph.

Investment Returns

Clearly Pollin presumes there is nothing inevitable about the system of perverse incentives that engorges GDP and proposes that the proceeds of growth can, in effect, be “siphoned off” to fund investment in clean energy. In this vision, the transition to clean energy would be funded by a portion of the increment of national income rather than requiring diversion of a portion of the “principal” thus making ecological salvation economically painless. Pollin’s Green New Deal posits investment in clean energy as a supplementary “built-in mechanism” that will gradually wean GDP from dependence on fossil fuels (once “those powerful vested interests”, who “wield enormous political power” have been defeated). The faster GDP grows, in this vision, the more rapid will be the transition to clean energy because more growth will automatically result in more investment.

The word “investment” does a lot a work in the Pollin plan. What the term abbreviates is a complex process of institutionalizing selection criteria for the funding of projects, project design and budgeting, ranking and selection of competing projects, project oversight and post-project evaluation of success in meeting objectives. There is not some ready-made pool of self-evidently effective clean energy projects. The whole process — conducted presumably by hundreds of agencies operating in hundreds of countries — is subject to cronyism, administrative padding of costs, inept selection criteria, mislabeling, miscalculation, lobbying, boondoggles, administrative capture by powerful vested interests and outright embezzlement. There is no “built-in mechanism” to guarantee a “trillion dollar annual investment in clean energy” delivers what the name advertises.

In short, investment in clean energy is not “apredictable, controllable physico-chemical process, such as boiling an egg or launching a rocket to the moon.” The successful outcome of such a programme would require “a permanent struggle in continuously novel forms” not simply the once-and-for-all defeat of thosepowerful vested interests who wield enormous political power.

Deja Vu All Over Again

Forty-six years ago, Robert Solow placed his faith mainly in the “built-in mechanisms” of the price system, which, he claimed, “tends to turn off consumption [of scarce resources] gradually and in advance.” Evidence for the success of this mechanism was to be seen in the increasing productivity of a variety minerals used as industrial inputs. But pollution presented an exception to this rule because it escaped the price system. Solow offered a remedy for that defect – investment in pollution abatement:

An active pollution abatement policy would cost perhaps $50 billion a year by 2000, which would be about 2 percent of GNP by then. That is a small investment of resources: you can see how small it is when you consider that GNP grows by 4 percent or so every year, on the average. Cleaning up air and water would entail a cost that would be a bit like losing one-half of one year’s growth, between now and the year 2000.

Robert Pollin’s critique of degrowth and his proposed alternative of a Green New Deal unwittingly recycles Robert Solow’s 1973 rebuttal to TheLimits to Growth. Pollin substitutes the euphemistic “decoupling” for Solow’s more conventional “productivity.” He acknowledges criticism of GDP and then ignores those criticisms when comparing degrowth and Green New Deal scenarios. He updates, refines and globalizes his investment target to one trillion dollars from Solow’s $50 billion, although both figures are presented as approximately the same percentage of annual gross product.

Pollin’s one major digression from the Solow blueprint is a curiously nostalgic one. He stresses the need to defeat “powerful vested interests” of the fossil fuel industry who “wield enormous political power” and charges the degrowth perspective with “the critical error of ignoring the reality of neoliberalism in the contemporary world.” Yet Pollin makes no suggestion about how those vested interests might be defeated or “how to put capitalism back on the leash that prevailed during the ‘golden age’ [before the era of neoliberalism].”

Speaking at a symposium on The Limits to Growthat Lehigh University in October 1972, Robert Solow could not have foreseen the military coup in Chile the following September that ushered in the regime of neoliberalism nor the OPEC oil embargo a month later that ushered in a new era of petro-political economy.

_________

[1]Robert Solow, ‘Is the End of the World at Hand?”Challenge, March/April 1973, pp. 39-50.

[2]Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, ‘Energy and Economic Myths’, Southern Economic Journal, January 1975, pp. 347-381.

[3]Jacques Grinevald and Ivo Rens, Demain La Décroissance: Entropie – Écologie – Économie,Lausanne, 1979.

[4]Fred Block and Gene A. Burns, ‘Productivity as a Social Problem: The Uses and Misuses of Social Indicators’, American Sociological Review, December, 1986, pp. 767-780.

[5]Nate Aden, ‘The Roads to Decoupling: 21 Countries Are Reducing Carbon Emissions While Growing GDP’, World Resources Institute blog, 5 April 2016.

[6]Consumption-based CO2 emissions estimates are from ‘The Global Carbon Budget 2017’ updated from Peters, GP, Minx, JC, Weber, CL and Edenhofer, O 2011. Growth in emission transfers via international trade from 1990 to 2008. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, 8903-8908. Employment estimates are from International Labour Organization, ILOSTAT, Key Indicators of the Labour Market, Status in Employment.

[7]William Stanley Jevons, The Coal Question, London, 1865.

[8]On decoupling as fantasy, see Robert Fletcher & Crelis Rammelt, ‘Decoupling: A Key Fantasy of the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda’, Globalizations, 14:3, pp. 450-467. They write:

“[The] dramatic disjuncture between the blind optimism of the decoupling proposal and the daunting (thermodynamic, financial, and distributive) obstacles in the face of its realization suggests that the concept works as a Lacanian fantasy, presenting both the prospect of sustainable development at some unknown future point and a convenient a priori explanation for why this aim is not achieved. …

“The pressing danger, of course, is that even if decoupling is infeasible, it will take some time for this to be demonstrated to the satisfaction of its proponents as well as those merely using it as a smokescreen to continue business as usual for as long as they still can. Thus, the decoupling fantasy may allow us to maintain an increasingly destructive path with both the promise of success and demonstration of its impossibility deferred into the future.”

[9]Maurice Dobb,Wages, Cambridge, 1928.

[10]Clifford Cobb, Ted Halstead and Jonathan Rowe ‘If the GDP is up, Why is America Down’, Atlantic Monthly, October 1995.

[11]Simon Kuznets, ‘National Income: A New Version’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, August 1948.

[12]Roefie Hueting, ‘Three Persistent Myths in the Environmental Debate’, Ecological Economics,1996, pp. 81-88.

[13]Angelo Antoci and Stefano Bartolini, ‘Negative externalities, defensive expenditures and labour supply in an evolutionary context’, Environment and Development Economics, October 2004.

[14]Irving Fisher, The Nature of Capital and Income, New York, 1906.

This is why economists are hated by almost everyone else. This article is mental masturbation destined for initiates and replete with inside jokes and jabs that only his Brethren will understand. The author has taken a serious issue and turned it into an academic exercise in obfuscatory scriveny. Honestly, anyone who feels compelled to use “otiose” should use it in the title, not the body, which would save a bit of reading for everyone.

Well to be fair, it was originally published on Econospeak.

This is a finance and economics site. I don’t take well to readers criticizing perfectly mainstream and readable economics posts. Your reaction is like going to a Japanese restaurant and being upset that all you can order is sushi and sashimi. No one is holding a gun to your head to read these posts.

Sorry, but an overwhelming percentage of the posts on this site are written in clear and understandable prose designed to convey meaning and understanding. This article was not.

And I like Japanese food. I have eaten in dozens of Japanese restaurants around the globe including Japan; even in the most expensive in Tokyo the menus had pictures!

“When you find yourself in a hole, stop digging”

There’s nothing wrong with the post, in fact it makes a very important point. I’ve seen Pollin interviewed for years (on Real News) and I think he’s a decent guy and has some good ideas, but was suspicious that he wasn’t being thorough enough in his research.

Author is right to pose hard questions. I don’t think society has yet figured out a model of how to pull off good/high living standards combined with lower energy and resource consumption.

If the article’s a bit thick for you, maybe you should challenge yourself to step it up once in awhile? Or, if not, like Yves suggests, just move along to the next post.

With all due respect, I have read many articles on this topic that were way easier to understand.

“If the article’s a bit thick for you, maybe you should challenge yourself to step it up once in awhile?”

Maybe if you could trust the author that the argument couldn’t be stated more simply. And besides, it is not the readers’ obligation to decode what the they want to say. If the writer for whatever reason fails to get their point across, that’s their problem, at least if they write to be understood and not just to feel intellectually superior.

Scream,

If you don’t like my prose but want to participate in the conversation, read the comments.

I wrote this essay as a reply to an essay by Robert Pollin that was published in the New Left Review. It is not meant as an introduction because I assume that anyone reading a reply to an essay can also read the essay to which it is a reply. This is how conversation works. When you come in in the middle, you need to pay attention for a while before you catch the drift.

“Otiose” means the comparison serves no practical purpose. Far from being an obscure term, it is virtually a cliche to call comparisons otiose.

Otiose may be a cliche, but why write in cliches? I still find it intentionally obscure. Why not simply say something is pointless or useless?

I am curious to know the origins of the quotations you use in the last paragraph of “Investment Returns.” I could not find them in Pollin’s article. Are they from some other article?

Your response to Pollin’s article appears to me to be more aimed at nitpicking and developing small issues into large ones. For example, while you may be correct in your interpretation of Jevon, this does not mean that Pollin is wrong in this context. Citing the work of a 19th century economist looking at coal-fired steam engines does negate the assumptions made by Pollin.

I don’t dispute that you are responding to Pollin, I simply have a hard time seeing past what appears to be some sort of animosity. Pollin wrote about investing, You went on a mini-rant about how he fails to define investment, how investments are subject to political considerations, manipulations, and cronyism, and how nothing can guarantee that this one trillion investment will take place. I suppose Pollin could channel the ghost of Bertrand Russel and rebuild the economics dictionary from first principles with your input and then use “investment” in a manner that satisfies you. But surely his argument does not hang on the definition of “investment”. That is but one of the arguments.

Citing Fisher reverentially is your right but Pollin addresses his concerns over use of GDP to measure growth and prosperity. It seems unreasonable to demand that Pollin include an entire treatise defining and quantifying a new measure of growth which encompasses Fisher’s desiderata as well as environmental externalities. There are few economists or financial professionals who are entirely comfortable with GDP and Pollin is not among them. Again, does the problem of defining GDP destroy Pollin’s entire argument or not?

I enjoy the commentary. I read your article and I read the original article. And, I stand by my opinion that I found most of your response to Pollin to be otiose.

Oh, O.K. I think your point, then, Scream, is that you DISAGREE with me. That’s fine. What you seem to be telling me, then, is that my reply to Pollin would have been clearer and more effective if I had simply said, “this is all bullshit.” You may have a point. But I disagree with you.

I don’t disagree with you. I have no opinion of your opinion because I frankly don’t know exactly what your opinion is. I am simply taking issue with the character of your response to Pollin. You can call Pollin’s essay bullshit and that might be a better answer than the one you gave. My point is that your critique of Pollin is centered around things like an esoteric argument over the definitions and utility of terms like “income” and “GDP”.

You and he acknowledge that those are poor terms and inadequate, but I don’t see anywhere where you offer better terms and definitions. I am curious to know if you don’t toss out the entire body of economics or at least macro since most works refer to income and GDP.

So, let me ask a simple question. Why is Pollin wrong? Is it because using “income” is inadequate despite having no better solution. Is it because GDP is a poor measure of many things but we do not have an adequate alternative? Or is it for more fundamental reasons?

If you think the argument over the use of GDP growth as an indicator of national welfare is esoteric, I would suggest you follow the link to “If the GDP is up, Why is America Down,”

Way to go scream!!

did you read what he said workingclasshero, reduce consumers. That’s you. Let’s make a techno-utopia with a massive unheeded underclass. It’s that prius driver thing where they’re so self satisfied… “Harsh,but neccesary, I believe.” All of the savings he claims will come through will be because he’s decreasing energy use by decreasing people. How?

I found the quotes I was referring to. They are effectively from Georgescu-Roegen and not Pollin. They are not in quotes in this post (except where you requote at the end) and not indented as they are in your original article.

Yes, it’s unfortunate that some of the formatting has been lost in the transfer from EconoSpeak to NC. Please refer to the ES version to identify citations.

Not that it’s technically a bad essay, as it does go painstakingly point by point with the required rigor for a rebuttal.

As you can imagine by now, I share the same opinion on the matter.

It’s just that Robert Pollin (and many other tribal economists) has such an appallingly naive notion of how the world works, such baffling shortcomings of BASIC SCIENCE, that it wasn’t necessary to go to such length to shatter his “argument” unless you wanted to induce sleep instead of productive righteous rage in the readers’ mind.

I guess it’s a classic case of “don’t bother with the rapier, …just get the sledgehammer”.

All points could have been made as clear and as rigorous with fewer words .

No need to prance around.

Autism should be beaten out of economist for all the damage it’s done.

I view the presence of words I don’t know as a learning opportunity. For example, “scriveny”… appears to be a nonce back formation from scrivener, since it doesn’t appear at dictionary.com, or in my online OED and AHD. Learn something new every day, eh?

If the reading level of an article is too high for you, either educate yourself or don’t invest time in it. Otherwise, it’s a big Internet, and I hope you find the happiness you seek elsewhere.

Thank you for your kind invitation to depart this site and never return, but you have misunderstood me. The reading level of the article is not too high for me. If that were the case, I would not have been able to read it and understand it. I don’t believe the submission is worthwhile or useful, not because it is too dense for me, but because it does little to contribute to the underlying discussion of resource use and pollution. I believe my comments here explain my point of view.

You believe what you want to believe, but one thing is for sure, Pollin ain’t got no politics to stand against neoliberalism. And part of the reason is the way he ‘Solow’ talks. As the essay pointed out.

“If the reading level of an article is too high for you, either educate yourself or don’t invest time in it. Otherwise, it’s a big Internet, and I hope you find the happiness you seek elsewhere.”

Why such hostility? I presume the author wants people to read and understand their argument. Why should using common words (or at least explaining the uncommon) be such an imposition?

If you think Sandwichman’s vocabulary is otiose, you should read Philip Mirowski.

I have and do. I regard his style and obscure vocabulary off-putting but I highly regard most of his arguments and conclusions. The trouble with much of Mirowski’s vocabulary is that it tends toward usages that seem to derive from social science jargon.

Very interesting and thought-provoking. I’m NOT an economist and I enjoyed reading this piece. Not sure that I agree with all of the conclusions, but it got me thinking in ways that I usually don’t. Thank you.

or to sum up: 3 things that the world needs to do that won’t happen….

buy less stuff, shorten the supply chain, use more nuclear power

(as much as i’d like for it to happen, wind + solar +battery ain’t going to cut it for the intermediate-term).

Nuclear’s complexity and its necessary centralization rules it out, from what I can see.

Why is centralization necessary? I use to have a buddy that had run the reactor on a sub. He was vehemently opposed to the massive reactors we have but he often said small scale reactors that could power a town or serve industrial needs would be much safer and make more sense.

The solution to dangerous complexity is more complex systems?

Well, that’s the thinking behind SMR’s (small modular reactors). For now they are too expensive (from what I know nuclear reactors have high economies of scale), the idea is to make them less expensive by mass producing them assembly line style. Whether that will work, I have no idea.

And number four: find a safe and acceptable way to enforce population reduction.

Boiling it down the author seems to be saying that capitalism and CO2 go together like bacon and eggs and claims to the contrary are a “headfake.” Widgets must be sold and (energy) resources consumed. Off shoring industrial activity to China or some other country doesn’t change the equation.

And surely this is the great dilemma that AGW scolds often don’t want to concede. To truly address the problem will require an as yet undiscovered scientific breakthrough or a huge change in all our social and economic arrangements.

But the good news is that humans are adaptable and capable of change when reality–the recent hurricane in my region might be an example–finally intrudes on the theorists. There was once a revolt against our materialistic US culture but the economic “think of the jobs” empire struck back and it didn’t last. But with enough painful comeuppance we may yet get our Age of Aquarius.

>ain’t going to cut it for the intermediate-term

And nuclear is? Yeah that V.C. Summer plant is really pumping it out now… oh, wait. Ok well it will soon be that’ll show them… what, cancelled?

I could have made this post on my battery-powered iPhone which got charged last night on pure wind power but am at work and won’t willingly fight Jobs spellcheck if I don’t have to…

Nuclear power plants take decades to come online. That takes us beyond the intermediate time frame. We may as well go full speed into developing solar and wind with “battery” storage as the timing for coming to fruition would be similar and much less costly and dangerous.

With some hesitation I offer these comments:

It does seem that Sandwichman is very right to argue out that Pollin has failed to think of production as a transnational process that can result in the transfer of carbon emission from one side of the planet to the others.

It also seems that he correctly draws our attention to the, to put it strongly, arbitrary nature of valuing productive activity. (Anyone who has followed arguments made by feminists concerning the exclusion of household labor from GDP calculation is familiar with the issue.) But I’m not sure that Sandwichman accomplishes anything more than alerting us to a potential fudge, not that one has been made.

His criticisms of Pollin’s supposed minimization of the political burdens of the transition he proposes, however, strike me as unfair. At one point he appears to argue that Pollin is trivializing those burdens by cloaking them as merely technical problems associated with shifts in investment. But then, when he does acknowledge that Pollin has indeed referred to “powerful vested interests,” he faults him for not providing a strategy for bringing them down.

This sounds like a demand for radical boilerplate. Or, at least a somehow more adequate acknowledgement that we can expect intense political conflict over what I guess you could call massive and widespread asset stranding, as material and human capital is revalued as part of the Green New Deal.

But if that’s the case, it seems that Sandwichman has himself carried out a fudge of sorts. Back upstream, where he refers to the writings of Fisher and others, he doesn’t anticipate this final political (and cultural) determination of value, but instead makes it sound like previous work offered clarifications that Pollin ignores. I’m left wondering whether Sandwichman himself overestimates the relevance of those writings in his rush to charge Pollin with a scholarly oversight. I’m unsure of the terminology here, but in the transition under consideration there will be phase when invisible handish market determination of value will have to be suspended. What is the relevance of Fisher et al then?

but in the transition under consideration there will be phase when invisible handish market determination of value will have to be suspended.

well we do have mark to model accounting nowadays, I think that is still going on, no?

Doesn’t that only specify what would become the locus of the problem? What model would you use? If carbon spewing assets are going to be devalued, what will be the accelerated rate of depreciation?

sorry, not a critique of your comment, just a thought that we’ve already gone down the rabbit hole on mispricing, and getting “our bettors/s” to face complex realities that involve sacrifice on their own parts ( they seem more than willing to sacrifice everyone else) is one of those facts not in evidence, I just see more silo-ing instead. I suppose that I’m a pessimist who doesn’t think we can purposefully remove ourselves from the mess we’ve made, and we’ll give up fossil fuels when we have them torn from our cold hands.

This reminds me of the drunk looking for his car keys under the street light because it is easier to see.

I think the real problem with renewable energy is the lack of a metering mechanism for sunlight and wind. Since there is no fuel cost and no industry needed to produce fuel, the renewable energy powered economy will be fundamentally different. Similarly, well made electric motors last much longer than internal combustion motors, implying that demand for manufactures will be significantly reduced. To take it even further, demand enhancing practices such as planned obsolescence may be replaced by durability and recycling criteria. Then it follows that the economic paradigms will be different, even to the point that money indicators become much less useful. So, IMHO, it is almost a truism that the present system will not work with renewable energy. I do not think the prospective obsolescence of mainstream economics implies that renewable energy is unworkable.

Much of renewable energy represents hydrocarbons pulled from the ground and converted to renewable energy devices.

see https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/?page=us_energy_home

Note that only 11% of US energy consumption comes from renewables and some of these “renewables” are not the solar/wind one might expect..

Breaking this renewable 11% down (click on pie chart at link)

2% is geothermal

6% is solar

21% is wind

4% biomass waste

21% biofuels

19% wood

25% hydroelectric

——- (only sums to 98% of 11%, but close enough)

Roughly 80% of USA energy consumption is from CO2 producing hydrocarbons (oil, coal, gas)

In my opinion renewables cannot scale up to matter much in any conceivable time frame, especially when even more hydrocarbons are used to produce them (wind/solar fabrication).

I fault the economic profession for being very human-centric in their judgments of economic progress.

If one looks at the other life-forms on this fine planet, the species die-off, referred to as the Sixth Mass Extinction indicates that our fellow resident animals are not doing well.

I suspect we will be following them, wondering what happened.

I won’t be wondering one bit. I see it with my own eyes everyday, as, for example, my neighbors trying to spray their manored lawns to perfection with a dandilion chemical spray, say .. or some gnarly fungicide, while I, on the other hand, try to enhance my surrounds to attract pollinators. I do not weld the influence like the Big Moneyguns such as Bayersanto and their ilk .. but I try to do the right thing just the same.

I’m hoping the meek truly win out in the end ..

Well, if roughly 80% of USA energy consumption is from CO2 producing hydrocarbons, then we know which part of the energy mix we will have to do without. Has anyone really considered how much energy consumption is mere consumer indulgence? Probably around 80%. My point is the future will be much different from the present, and present-day received wisdom is basically worthless. I realize, however, the powers that be will struggle mightily to make themselves indispensable and fight off any meaningful change. Then there is the point that most people would not know what else to do. So I have no problem understanding the appeal of the article.

Sorry Yves, but I have to agree with TheScream about the mental masturbation. The author, who I usually sympathize with, is over thinking the subject.

We need less people, doing less stuff . The various Green New Deals would actually increase greenhouse emissions because all the Green New Deal activities would produce emissions. It takes emissions to manufacture a solar panel. It takes emissions to build mass transit. It takes emissions to commute to your Green New Deal job. And so on. Maybe after all the dust has settled and the solar panels are in place and the mass transit is in place, then emissions would decline, and maybe that would have worked if we had undertaken it 50 years ago.

We need less consumption — which means less income (what’s the point of having income other than consumption?).

The surest way to reduce our environmental footprint is to have fewer feet — which no Green New Deal dares to address.

It’s difficult to see a viable path forward, given the enormity of the problem, the slow pace of human evolution, and capitalism’s need for growth. Unless a practical way is devised to suck greenhouse emissions out of the atmosphere (i.e. seeding the ocean with iron dust), we’re doomed.

I agree with most everything you say but not the last two words. It’s only fairly recently that humanity became aware of its daunting environmental quandary, the essential incompatibility of greed and growth-driven capitalism with the health and viability of the planet itself. Instead of writing off the future of our species (and many other lifeforms) in light of this unwelcome but necessary knowledge, shouldn’t we instead be fervently exploring alternative and sustainable economic systems and the ways we might transition into them as quickly as possible? Many say that it is easier at this point to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism. All the more reason, I say, to get harder at work on the latter. Where does our ultimate faith lie, in blind unyielding fate or in the human spirit?

https://newtonfinn.com/

I have some faith in the human spirit.

The problem is the projected supply of “human spirits” either has or will exceed the carrying capacity of our planet.

Look to our companion fellow creatures for evidence of that.

This beautiful quote from Paul Stamets, from his “Fantastic Fungi: The Hidden Fruit”:

“If we don’t get our act together and come in commonality and understanding with the organisms that sustain us today, not only will we destroy those organisms but we will destroy ourselves. We need to have a paradigm shift in our consciousness. What will it take to achieve that?

If I die trying but I’m inadequate to the task to make a course change in the evolution of this planet…okay I tried. The fact is I tried. How many people are not trying. If you knew that every breath you took could save hundreds of lives into the future had you walked down this path of knowledge, would you run down this path of knowledge as fast as you could.

I believe nature is a force of good. Good is not only a concept it is a spirit. So hopefully the spirit of goodness will survive.”

Both insightful and inciteful, sandwichman dares to take a stand. When I read these wonky posts, and I’m in 3 paragraphs and the coffee hasn’t really kicked in yet, I re start at the bottom, read the conclusion and then go up incrementally, bottom para, 2nd to the bottom, and then move into the piece in this manner, eventually coming to a point, as in this case where, for one example, the reference is “jevon’s paradox” and I don’t know what that is, but I can then go into the above and extrapolate from the conclusion what he premise means. Reading this way, I have control c’d many sections, which means there is a lot of content here, and the last one I grabbed was this one:

Economists “have not known where to cease calling the concrete instrument income and begin calling its use income instead. In their hesitation they have in some cases ended by including both. By so doing they commit the fallacy of double counting.”

And my overall takeaway in consolidated form is that being healthy is unpaid labor for maintaining the tool that is at the base of the gnp calculation, as all household maintenance is an unpaid gift to gnp,, just as the pcb’s in the duwamish were/are a contribution to boeing’s bottom line…that’s a real public/private partnership. Sandwichman also reels in the paradox of more jobs equals more pollution, and no one seems to be able to jump that hurdle. A fine but complicated to the layman post. The very reason to read nc. I’m sure I missed some things so feel free to add…

Jevon’s paradox is one of those things that get theoreticians very excited. It’s like backwardation; economists tortured themselves for centuries trying to suss out backwardation. They finally came up with “convenience yield” and went their merry way. Jevon’s paradox,which is hardly paradoxical to people using real things in the real world says that introducing efficiencies increases use of the input or raw material.

Jevon’s studied coal use in industrializing Britain. The shocking paradox was that coal use increased when an efficient steam engine was designed. I find this akin to saying that economists were shocked to discover that jet travel exploded when engineers moved from designing military jets to more efficient passenger jets. Jevon was perhaps confused because he had only seen one or two inefficient steam engines. When the new design increased efficiently radically, he was amazed to see people building and buying them willy-nilly and therefore using lots of coal.

Using Jevon’s 19th century paradox here is questionable. The Green Plan does not propose building Tata Nano’s. It suggests building fewer, more efficient cars and reducing the number of cars overall (I use this as a possible example, not a citation from Pollin). Citing Jevon’s Paradox as a distinct and separate issue is too easy. The point of the plan is to lower consumption by increasing efficiency AND decreasing the number of consumers. Harsh, but necessary, I believe.

“Using Jevon’s 19th century paradox here is questionable.”

Pollin wrote about the rebound effect. Jevons paradox is another name for the rebound. I was replying to Pollin’s essay.

“The point of the plan is to lower consumption by increasing efficiency AND decreasing the number of consumers.”

And, if you do that, you also reduce the demand for labor (according the rebound argument). The fuel bone is connected to the job bone.

I agree that Pollin wrote about the rebound effect, but he postulates a different set of conditions, conditions which could be radically different from Britain in 1865.

As you pointed out in Pollin’s quote, he is talking about reducing demand by increasing efficiency AND decreasing the number of consumers. This is NOT Jevon’s Paradox. Pollin seems well aware of the paradox and expressly indicates how to overcome rebound.

If your argument is that you require Pollin to maintain demand for labor, growth, innovation, etc. then you can toss in all the Jevon you want. It does not appear to me that Pollin is advocating that. The fuel bone is indeed connected to the economy bone, but Pollin is arguing for a disconnect. He is arguing for a break in Jevon’s Paradox through understanding it and making a pointed effort to eliminate it and achieve real reduction in fuel or resource use.

So, you can say you disagree with him which is your right. But tossing around Jevon as if that name alone justifies your argument is not acceptable to me. Additionally you appear to be arguing a different thing from Pollin.

“tossing around Jevon as if that name alone justifies your argument”

I don’t think I was just “tossing around” a name. What I was trying to point out was that the rebound effect, as formulated by Jevons, doesn’t refer only to fuel efficiency and consumption but also to employment and that whatever the extent of the supposed rebound, the effects on fuel consumption and employment are not independent of each other.

Pollin discussed — and minimized the importance of — the rebound effect without acknowledging this interdependence between fuel economy, fuel consumption and job creation. That makes his analysis importantly incomplete.

I don’t “toss around” the Jevons paradox as some sort of bugaboo. I raise it as an empirical question that can only be adequately addressed by considering all of the critical dimensions of that question.

The Green New Deal as described by Pollin doesn’t seem much like the Green New Deal we Greens are talking about, which is just to put unemployed and underemployed people to work improving the sustainability of their communities.

The problem is power, there are many simple things that could be done, but in our global system, anything that doesn’t actively make billionaires even richer is ignored or attacked by anyone with power.

Is the solution to directly attack the power structure, or ‘collapse now and beat the rush’ and build something independent?

There are just some problems don’t have a solution. There isn’t going to be a politician, green or otherwise, from any country that convinces the electorate that what we need is a zero-growth program. I never understood the Archdruid’s maxim as anything other then an individualized response that might help navigate the next phase of collapse. I don’t think he ever really intended it to be a systemic solution.

The real solution is probably not to think about it. People have a hard enough time contemplating and dealing with their own mortality issues and contemplating the death of industrial civilization is several steps beyond that. The growth and sustained use of hydrocarbon energy isn’t likely going to last into the next century. We’ll probably end up cooking the planet or killing each other over the Arctic if it’s full of hydrocarbon resources.

Soooo, yeah, frack thinking.

Pollin completely disregards the other resources that’d be consumed through the massive growth of “clean” energy. Instead of consuming hydrocarbons for energy-related purposes we’d see a huge increase in non-renewable resources being used; rare earth metals, lithium, and uranium. The mining and processing of these resources is far from being a clean process. The fantasy of virtually unlimited productivity gains and economic growth won’t dissipate easily though.

What if we ghettoed artisans by subsidizing them.

Then we could drop production numbers but price in the waste labor. Like making shaker chairs by hand and painting not with acrylic but egg yolks?

You could drop exotic car numbers, etc. with hand crafting…

Seems the base issue is valuations and an addiction to “cheap.” Less luxury goods versus more cheap crud…

Guess you need to pay wages tho.

heavily fund the national endowment for the arts, make it part of the jobs guarantee, along with food foresting under the dept of interior, another JG…

Growth has to stop. Thermodynamics demands it. Probably peak oil and the failure of alternatives to cover that loss will stop growth anyway. Up to this point, energy use has out stripped population growth, so that even if population growth stops or reverses (plagues anyone?), energy use will continue to rise (Especially if we get more efficient in its usage–Jevons again)

” I’ll just mention that energy growth has far outstripped population growth, so that per-capita energy use has surged dramatically over time—….So even if population stabilizes, we are accustomed to per-capita energy growth: total energy would have to continue growing to maintain such a trend…the Earth has only one mechanism for releasing heat to space, and that’s via (infrared) radiation. We understand the phenomenon perfectly well, and can predict the surface temperature of the planet as a function of how much energy the human race produces. The upshot is that at a 2.3% growth rate (conveniently chosen to represent a 10× increase every century), we would reach boiling temperature in about 400 years. ”

I rather suspect that we crash back to some 16th century energy use long before that, but his argument is convincing that continuous, never ending growth is thermodynamically impossible.

It’s a conversation between an economist and a physicist. Very amusing.

https://dothemath.ucsd.edu/2012/04/economist-meets-physicist/

Growth has to stop. Thermodynamics demands it.

Only for some definitions of growth. One of the few benefits of NIPA accounting is that activities that use few resources that no one would necessarily think of as (real) growth can be counted as economic growth if there is a way to monetize them. So what we need are new economic categories and relationships that allow us to get paid (the equivalent of) 100K per year for raising our children or taking care of our parents and price fossil fuels so that they are prohibitively expensive. That still wouldn’t answer the question of who gets access to refrigeration and air conditioning and who doesn’t, and how that decision gets made.

In “theory” GDP could be made to grow just by adding the value of leisure and subtracting the cost of pollution. But in practice, GDP growth has an agenda that isn’t met by those changes. A clue comes from the title of Keynes’s How to Pay for the War. Conventionally measured GDP indicates the potential for generating government revenue through taxation. So it is not “things we value” but specifically incomes, goods and services that governments can tax than matter.

particularly that of labour-saving machinery eventually increasing employment.

yes and

particularly that of labour-saving machinery eventually increasing energy consumption.

We trade “labor saving” for fossil fuel consumption, do not fully cost the effects of fossil fuel use, and effectively mortgage our future.

As we can see from the Hurricanes and Fires in the US.

In the first place, Sandwichman isn’t on economist; he;s an adjunct teaching labor studies in the sociology dept. of Simon Fraser U.

I haven’t re-read this piece, since it’s long and I already read it when first posted. But in a nut shell what it seems to me to be targeting is the stock-flow confusions concealed in Pollin’s level of macro-economic abstraction/. The assumptions that trend growth will yield more “resources” in the future than currently exist to deal with environmental problems and that inputs to production can be readily substituted for when one or another is in short supply because of inherent limits, (and the price mechanism alone would take care of the problem), are, looked at more concretely, fallacious. Further “capital investment” can’t really be treated as an abstract, undifferentiated quantity, to be plugged into an equation. It’s true that investment is a component of GDP and a form of spending that can stimulate “growth” and that an increase in investment and a corresponding decrease in consumption spending would be required to attempt to deal with AGW&CD. But, even leaving aside measurement problems and confusions between monetary flows and actual use-values, the concrete types of investments and their systematic coordinations and integrations need to be specified and in ways and with institutional mechanisms that can’t simply be attributed to “markets”, even as a vast amount of current capital stocks and infrastructure would need to be written down eventually to zero, {including the pile of financial “assets” that sit atop and derive from them) at rates of depreciation much faster than is assumed to be “normal”, diminishing profits, while a correspondingly large amount of new investment must be raised and implemented. Needless to say, environmental and natural resource limits can’t be wished away from this whole process though simply abstracting from them. What’s more, not only does the current nexus of capital valorization need to be progressively diminished, but scale economies and ever expanding output as a source of high profits would need to be reversed, shrinking the “capital to output ratio”, expressed in quantitative terms rather than actual uses and needs, decreasing the profits and thus the monetary value of capital stocks, rendered in relative terms more expensive, thus decreasing the incentives for private investment. This amounts to a massive process of production switching, (which is why the WW2 economy is often evoked, not just because of the scale and urgency, but because of the need for planning and regulation), which can’t be captured by abstract linear extrapolation. And what especially needs to be attended to is that the reconstruction to an environmentally sustainable economy maximizes the direction and development of sustainable energy and resources to the development of sustainable systems. Energy is what does work and much work will need to be done to build up the renewable and sustainable alternatives (and clean up messes, such as nukes), and the more rapidly the alternatives can be implemented, the more they can contribute to further work, rather than counter-productively relying on current resource use. It’s the concrete difficulties and obstructions to that cross-over that Pollin’s essay completely elides.

Exactly. Stock/flow confusion, obfuscation and denial are rife in Pollin’s and Solow’s essays, although I do have to say that Solow’s 46-year old essay is far more compelling than Pollin’s two-month old one.

Economists seem to think that because they can abstract from the qualities of goods and services to their monetary values and then add up those values that it is just as easy to “abstract” back from those aggregate quantities to some imagined qualitative collection of goods and services. This would be laughable if it wasn’t killing us.

Pollin’s “Green New Deal” seems like a sly recipe for how to make an omelet without breaking into any eggs. Sandwichman builds his critique of the “Green New Deal” as though Pollin is operating in a world where economics applies. I believe Pollin is operating in a world where governments fund and run programs, like World War II, or on a smaller scale like the Space Race. I don’t understand why Sandwichman dug up Solow’s “degrowth” to compare with Pollin’s Green New Deal. I think it justs confuses and complicates the argument.

Sandwichman asserts: “Economic activity is not decoupled from the consumption of fossil fuel, as Pollin claims. It is the rate of change of economic activity that is decoupled from the rate of change of fossil fuel consumption.” But how important is this distinction to the argument? Pollin’s discussion of “decoupling” amounts to a fancy slight-of-hand for an “assume a can-opener” argument. Economic activity requires energy. Where does Pollin’s energy come from that’s decoupled from fossil fuels? Where are the detailed accounts and plans for the necessary transition to a state of even relative decoupling? And what bothers me most in Pollin’s argument is how he begs the question whether it is possible to replicate our present life-style based on energy from fossil fuels with a roughly equivalent life-style based on energy completely “decoupled” from fossil fuels.

At this point in the argument Sandwichman spends a little over 1200 words debunking GDP as an economic measure. [Are the readers of Econospeak big believers in GDP numbers or average incomes?] Sandwichman’s discussion of investment returns as the Pollin’s cost free means for funding the Green New Deal seems odd on two accounts. First it’s evident Pollin’s arguments seem to assume some sort of world government or at least some world agreement and adherence to that agreement and the usual economics just doesn’t seem to apply in Pollin’s world. “Investment” makes a nice word for Pollin’s arguments which Sandwichman does point out — like investing in an education. Second we have more than enough slack in our present overly austere economies to absorb a little spending on a Green New Deal. [I suppose that if the audience at Econospeak believes in GDP numbers some of them may have a little trouble with MMT?]

Pollin outlines his Green New Deal: “the first critical project for a global green-growth programme is to dramatically raise energy-efficiency levels” — OK. Next we assume away Jevons rebound effects: “But such rebound effects are likely to be modest within the context of a global project focused on reducing co 2 emissions and stabilizing the climate.” — What world is this project taking place in? Who is going to set-up and run this “world project” … the United Nations? Pollin follows with discussions of “Job creation and a just transition” and “Industrial policies and ownership forms”. He definitely isn’t talking about a Market based approach to the problem. Once we’ve traveled this far into the argument critique based on economic reasoning seems out of place, although Pollin does offer some homage to the world we live in: “Given the climate-stabilization imperative facing the global economy, we do not have the luxury to waste time on huge global efforts fighting for unattainable goals [things like a “standard of fairness” and hints at world wealth and income re-distribution] …”

So how does Pollin’s Green New Deal stack up compared to Solow’s “built-in mechanism” of the price system? They both attempt an end-around the conclusions of The Limits of Growth. Solow’s market can handle everything to make a smooth transition to something else as fossil fuels run out and Pollin assumes government can commandeer a small per cent of our economies replacing fossil fuels with non-fossil fuel energy sources with to our economies or way-of-life — both tell pretty stories. To my mind the crucial difference is that many of the actions Pollin thumbnails and argues for will be crucial, difficult, expensive, and they will greatly and negatively impact our economies and way of life. Continuing as we are is not going to end well.

“But how important is this distinction [between first and second derivative] to the argument?”

Indispensable. As john halasz points out there is a whole lot of stock/flow confusion going on in Pollin’s argument. Read john’s comment.

I had Robert Pollin confused with Michael Pollan and wondered why Michael Pollan was writing about a Green New Deal. [Is Robert Pollin an economist?] As for the “stock-flow confusions concealed in Pollin’s level of macro-economic abstraction.” — I missed Pollin’s subtlety. As I read Pollin’s discussion he seemed to just neatly assume away his problems then glide through a morass of diversions to hide his lack of arguments for his claims.

Pollin: [p. 9] “Energy consumption, and economic activity more generally, therefore need to be absolutely decoupled from the consumption of fossil fuels …”

“Economies can continue to grow—and even grow rapidly, as in China and India—while still advancing a viable climate-stabilization project, as long as the growth process is absolutely decoupled from fossil-fuel consumption.” <=== Assume a can-opener.

From this point Pollin moves into "investment" and other diversions …

transitional support for workers and communities, variations in the emissions, nuclear power and carbon capture and sequestration, raise energy-efficiency levels …

[p. 13]"There is no evidence that large rebound effects have emerged as a result of these high efficiency standards in Germany and Brazil." <=== Assume the problem away.

… average costs of generating electricity, pooh-pooh land use requirements for non-fossil fuel energy generation, regard variations in sunlight and population density etc., …

and still no warrants for the claim that "energy consumption, and economic activity can be absolutely decoupled from fossil-fuel consumption." Next Pollins moves on to the fundamental problems with degrowth, a green great depression?, and close urging us all to sing kumbaya together around his Green New Deal.

I’m generally a Sandwichman fan but I found this post all over the place. I quite liked Pollin’s piece when I first read it (a few weeks back?) but I read it differently than SWM. Given the heavy political lift of either degrowth or Pollin-style GND (but much heavier for degrowth), Pollin is trying to argue that GND is economically feasible (and thus politically feasible) and achieves acceptable ecological progress, while degrowth, due to the requirement of drastically declining standard of living, is not politically feasible. Then, being an economist, he waves a bunch of numbers.

I’m not sure he made a convincing case for GND – as SWM points out, his evidence of national decoupling should not make one as optimistic about current trends as it does Pollin – but it is certainly a worthwhile effort to crunch the numbers. My problem with degrowth is the same as Pollin’s: as far as I can tell, it’s a slogan masquerading as a political program. With degrowth, who exactly is supposed to do without car, refrigerator, air conditioning, and how is that decision to be made?

I also find it hard to understand the analogy between Solow and Pollin. Solow was basically arguing that (good) capitalist markets can adequately address fundamental ecological/environmental issues, though of course they might require some structuring by thoughtful economists (Solow solons). I don’t see Pollin making that argument at all. Pollin is trying to say, given the two options of degrowth or GND, achieving either of which requires a degree of deep social change the likes of which we have never seen, GND is the better option. He might be wrong about that. And he might not have made a plausible economic/ecological case for GND. But I have yet to see anyone do for degrowth what he has tried to do for GND.

Solow: “that there are no built-in mechanisms by which approaching exhaustion [of resources] tends to turn off consumption gradually and in advance.”

This piece I find to not be adequately attacked, either by Sandwichman or Roegen’s. The example cited here of turning off consumption gradually and in advance are best-case scenarios: commodities that are gradually depleted both at the local mine level and globally, which are not “base materials” but are materials that in most cases can be substituted.

I don’t recall any wars fought (at least publicly) over manganese — but we can name a few world wars that were crucially about energy resources (shifting over times).

I’d be quite surprised if the energy curves were at all similar — energy markets probably have nasty feedback effects creating oscillatory responses that in some cases don’t dampen but explode, unlike magnesium and molybdenum.

Why the soft ball on the fundamental issue? We know that in ecological systems, gradual and in advance responses are not the general solution, but a small subset. We see markets going into underdampening modes all the time. We have a plethora of data on famines (the original energy resource).

Why not call bullshit on Solow and his school? Why not say that in fact, it’s intellectually vacuous, from a pure scientific/physics point of view, without having to go into the sociology of the entire matter? Hard-core math nerds will tell you — expecting a soft sub-linear response is a special case. I can set up 20 coupled oscillators that cause a mess all over the place. Give me 8 billion coupled oscillators and who knows what I’m capable of. Anyone who linearizes that mess is just full of shit.

“Why not call bullshit on Solow and his school?”

Joan Robinson did. Elsewhere, I cite Robinson in calling bullshit on Solow. One cannot address all issues in every essay.

FWIW, this novice didn’t find anything wrong with the article. It’s obvs technical and about something I hadn’t read. Much more than I happen to have time to finish at this sitting. But I’d hardly count generous portions against a house.

I’ve liked what I’ve heard from Pollin, so it was good to get some criticism, thanks.

Regarding Doom. Look, the future of Earth is Venus. We can call it the neo-Hadean. Or maybe something more solar, since it will be the sun’s gassing off and expansion that will boil the oceans into the sky.

That’s a dead certain fact. In a few billion years, the sun will kill us all, then incinerate what’s left as it grows and swallows us whole.

It’s looking like we’re heading for that cliff already. I don’t see the change happening on the scale required, either. But you know what? I face death all the time; I drive.

I drive over a chasm called Deception Pass (no rlly, irl) twice a day, sometimes more. As you approach the twin-span bridge, the road narrows. Still one of the busiest state highways in the area tho. Full-size semis go by at what has to be 40+. So am I. Limit’s 30.

Between the spans you’re on Pass Island and have only seconds to make a slight left instead shooting over a cliff and 200′ to the water. Sometimes I’m sharing a curved bridge approach with an oncoming building doing 40 in the dark. For a while, I’m headed for certain death unless both of us do the right thing at the right time at the right speed.

We call that death-defying maneuver “traffic.”

So what if it looks like we’re doomed sometime down the road? Paraphrasing Doctor Who (Peter Capaldi? Matt Smith?), you’re throwing away perfectly good years where we’re entirely not dead yet.

Also regarding Doing the Right Thing. This is where agnostics rule.

I don’t have to know anything about consequences to know the right thing when I see it. We do the right thing because it’s the right thing to do. Not to prevent punishment or for some putative postponed payoff.

That’s why important to be in the world properly, so you don’t miss your moment thinking when you need to act now. It takes just that last quantum fluctuation. Much too fast for thought.

And as we all are each other, I think the proper basis of being human is compassion. So, acting in what I call an adoration field, vs damnation, looking for and to be loved, you see and do the right thing, and that’s all there is to it.

I mean, really, you want a receipt for that noble, selfless deed? You really need a carrot to get you to do the right thing? Just do It.