Investors keep desperately throwing money at private equity even as evidence continues to mount that it hasn’t delivered enough in the way of returns to compensate for its higher level of risk for over a decade. And recent studies paint an even worse picture, that investors who aren’t willing to bring private equity in house to cut out the egregious fees should punt on PE entirely and buy stocks instead.

The Financial Times has been dogging this beat admirably. It reported in August that Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou, based on Burgiss data, had concluded that private equity produced only S&P 500-like results since 2006. As we wrote then:

This is particularly damning, since as we have described repeatedly in past posts, the use of the S&P 500 is flattering to private equity by virtue of its average company size being much larger than typical private equity portfolio company sizes, hence you’d expect a higher growth rate. And for newbies, do not forget that the rule of thumb is that private equity should outperform the relevant public equity benchmark by 300 basis points (3%).

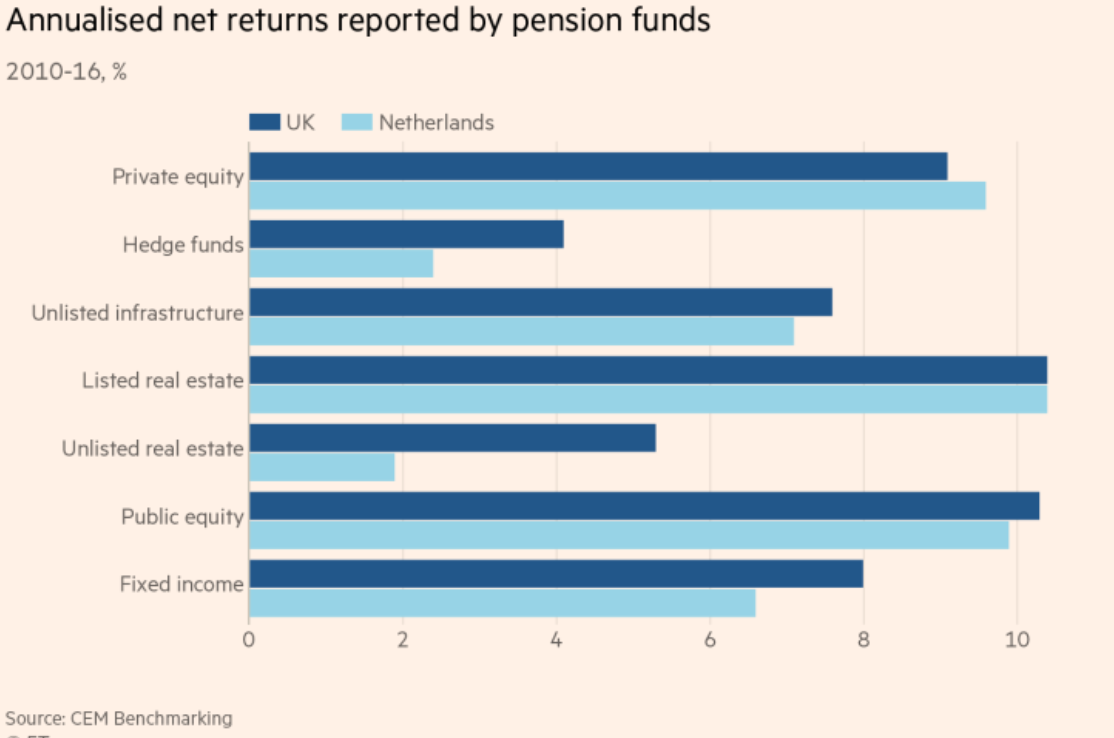

The latest study, by an authoritative source, the widely-used consultant CEM Benchmarking, which counts CalPERS among its clients, is even more negative than the recent Phalippou work. CEM found that both hedge funds and private equity underperformed stocks and publicly-treaded real estate since 2010, based on a study of UK and Dutch pension fund holdings. The poor relative performance of private equity was due entirely to the high fees of using outside managers; if investors were to participate in private equity at the cost level of in-house funds, it would have beaten other strategies.

An additional big negative was the CEM finding that private equity was more volatile than public equities. That should not be surprising; private equity should perform similarly to levered public equities. As we’ve pointed out repeatedly, private equity investors all all in on what amounts to valuation fraud, that is, the fund managers goosing the reported values of unsold investments, which account for a significant proportion of total reported returns until late in fund’s life. Investors particularly like the “smoothed,” as in phony valuations during bad equity markets. Fund managers mark down the valuation less than is realistic given prices they would likely realize (and the valuation standards are supposed to be current market prices). Those fictive prices make private equity look more attractive than it is two ways: by overstating the value at key points in a fund’s life (another well-documented juncture is around the time a successor fund is being marketed) and understating volatility.

The Financial Times story is not explicit as to CEM’s methodolody, but it seems likely that they chose actual cash flows.

Highlights from the Financial Times account:

The performance shortfall was due entirely to the higher fees charged by private equity managers. UK and Dutch pension funds paid an average of 415 basis points and 454bp in fees respectively to private equity managers.

“Private equity was the best-performing asset class before costs but public equity and listed real estate delivered higher returns after fees are taken into account for UK and Dutch pension funds,” said Alex Beath, a senior analyst at CEM.

He said there was a “huge disparity” of costs for private equity investments as in-house PE programmes run by pension schemes could operate for as little as 50bp annually while a fund of PE funds could cost up to 700bp a year…

Volatility for returns reported from private equity investments was also significantly higher than any other asset class. Differences in the styles of private equity managers employed by pension schemes can lead to even higher volatility.

Needless to say, not a pretty picture, but don’t expect investors who have pinned their hopes for salvation on private equity to abandon their faith any time soon.