Yves here. Haha, Lambert’s volatility voters thesis confirmed! They are voting against inequality and globalization. This important post also explains how financialization drives populist rebellions.

By Lubos Pastor, Charles P. McQuaid Professor of Finance, University of Chicago Booth School of Business and Pietro Veronesi, Roman Family Professor of Finance, University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Originally published at VoxEU

The vote for Brexit and the election of protectionist Donald Trump to the US presidency – two momentous markers of the ongoing pushback against globalization – led some to question the rationality of voters. This column presents a framework that demonstrates how the populist backlash against globalisation is actually a rational voter response when the economy is strong and inequality is high. It highlights the fragility of globalization in a democratic society that values equality.

The ongoing pushback against globalization in the West is a defining phenomenon of this decade. This pushback is best exemplified by two momentous 2016 votes: the British vote to leave the EU (‘Brexit’) and the election of a protectionist, Donald Trump, to the US presidency. In both cases, rich-country electorates voted to take a step back from the long-standing process of global integration. “Today, globalization is going through a major crisis” (Macron 2018).

Some commentators question the wisdom of the voters responsible for this pushback. They suggest Brexit and Trump supporters have been confused by misleading campaigns and foreign hackers. They joke about turkeys voting for Christmas. They call for another Brexit referendum, which would allow the Leavers to correct their mistakes.

Rational Voters…

We take a different perspective. In a recent paper, we develop a theory in which a backlash against globalization happens while all voters are perfectly rational (Pastor and Veronesi 2018). We do not, of course, claim that all voters are rational; we simply argue that explaining the backlash does not require irrationality. Not only can the backlash happen in our theory; it is inevitable.

We build a heterogeneous-agent equilibrium model in which a backlash against globalization emerges as the optimal response of rational voters to rising inequality. A rise in inequality has been observed throughout the West in recent decades (e.g. Atkinson et al. 2011). In our model, rising inequality is a natural consequence of economic growth. Over time, global growth exacerbates inequality, which eventually leads to a pushback against globalization.

… Who Dislike Inequality

Agents in our model like consumption but dislike inequality. Individuals may prefer equality for various reasons. Equality helps prevent crime and preserve social stability. Inequality causes status anxiety at all income levels, which leads to health and social problems (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009, 2018). In surveys, people facing less inequality report being happier (e.g. Morawetz et al. 1977, Alesina et al. 2004, Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Ramos 2014). Experimental results also point to egalitarian preferences (e.g. Dawes et al. 2007).

We measure inequality by the variance of consumption shares across agents. Given our other modelling assumptions, equilibrium consumption develops a right-skewed distribution across agents. As a result, inequality is driven by the high consumption of the rich rather than the low consumption of the poor. Aversion to inequality thus reflects envy of the economic elites rather than compassion for the poor.

Besides inequality aversion, our model features heterogeneity in risk aversion. This heterogeneity generates rising inequality in a growing economy because less risk-averse agents consume a growing share of total output. We employ individual-level differences in risk aversion to capture the fact that some individuals benefit more from global growth than others. In addition, we interpret country-level differences in risk aversion as differences in financial development. We consider two ‘countries’: the US and the rest of the world. We assume that US agents are less risk-averse than rest-of-the-world agents, capturing the idea that the US is more financially developed than the rest of the world.

At the outset, the two countries are financially integrated – there are no barriers to trade and risk is shared globally. At a given time, both countries hold elections featuring two candidates. The ‘mainstream’ candidate promises to preserve globalization, whereas the ‘populist’ candidate promises to end it. If either country elects a populist, a move to autarky takes place and cross-border trading stops. Elections are decided by the median voter.

Global risk sharing exacerbates US inequality. Given their low risk aversion, US agents insure the agents of the rest of the world by holding aggressive and disperse portfolio positions. The agents holding the most aggressive positions benefit disproportionately from global growth. The resulting inequality leads some US voters, those who feel left behind by globalization, to vote populist.

Why Vote Populist?

When deciding whether to vote mainstream or populist, US agents face a consumption-inequality trade-off. If elected, the populist delivers lower consumption but also lower inequality to US agents. After a move to autarky, US agents can no longer borrow from the rest of the world to finance their excess consumption. But their inequality drops too, because the absence of cross-border leverage makes their portfolio positions less disperse.

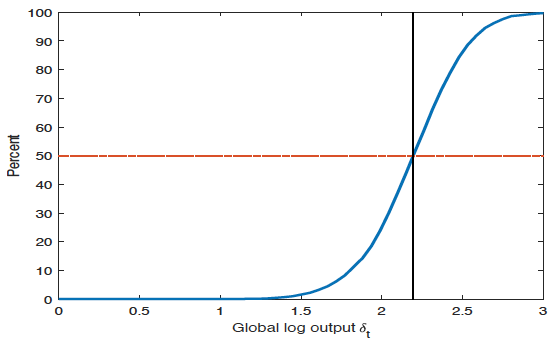

As output grows, the marginal utility of consumption declines, and US agents become increasingly willing to sacrifice consumption in exchange for more equality. When output grows large enough—see the vertical line in the figure below—more than half of US agents prefer autarky and the populist wins the US election. This is our main result: in a growing economy, the populist eventually gets elected. In a democratic society that values equality, globalization cannot survive in the long run.

Figure 1 Vote share of the populist candidate

Equality Is a Luxury Good

Equality can be interpreted as a luxury good in that society demands more of it as it becomes wealthier. Voters might also treat culture, traditions, and other nonpecuniary values as luxury goods. Consistent with this argument, the recent rise in populism appears predominantly in rich countries. In poor countries, agents are not willing to sacrifice consumption in exchange for nonpecuniary values.

Globalization would survive under a social planner. Our competitive market solution differs from the social planner solution due to the negative externality that the elites impose on others through their high consumption. To see if globalization can be saved by redistribution, we analyse redistributive policies that transfer wealth from low risk-aversion agents, who benefit the most from globalization, to high risk-aversion agents, who benefit the least. We show that such policies can delay the populist’s victory, but cannot prevent it from happening eventually.

Which Countries Are Populist?

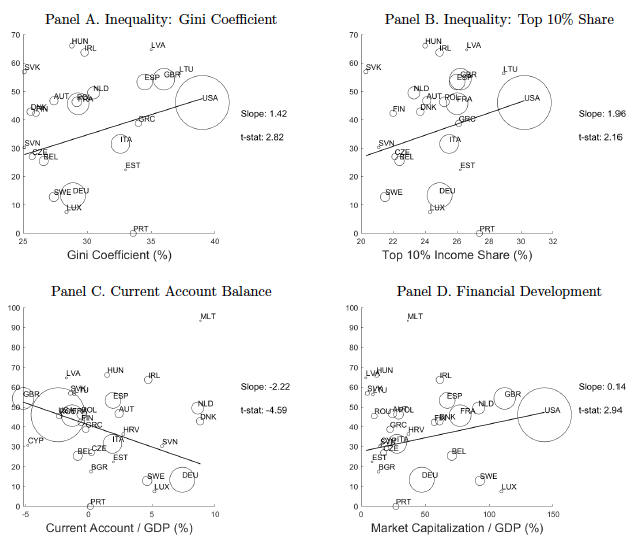

Our model predicts that support for populism should be stronger in countries that are more financially developed, more unequal, and running current account deficits. Looking across 29 developed countries, we find evidence supporting these predictions.

Figure 2 Vote share of populist parties in recent elections

The US and the UK are good examples. Both have high financial development, large inequality, and current account deficits. It is thus no coincidence, in the context of our model, that these countries led the populist wave in 2016. In contrast, Germany is less financially developed, less unequal, and it runs a sizable current account surplus. Populism has been relatively subdued in Germany, as our model predicts. The model emphasises the dark side of financial development – it spurs the growth of inequality, which eventually leads to a populist backlash.

Who are the Populist Voters?

The model also makes predictions about the characteristics of populist voters. Compared to mainstream voters, populist voters should be more inequality-averse (i.e. more anti-elite) and more risk-averse (i.e. better insured against consumption fluctuations). Like highly risk-averse agents, poorer and less-educated agents have less to lose from the end of globalization. The model thus predicts that these agents are more likely to vote populist. That is indeed what we find when we examine the characteristics of the voters who supported Brexit in the 2016 EU referendum and Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

The model’s predictions for asset prices are also interesting. The global market share of US stocks should rise in anticipation of the populist’s victory. Indeed, the US share of the global stock market rose steadily before the 2016 Trump election. The US bond yields should be unusually low before the populist’s victory. Indeed, bond yields in the West were low when the populist wave began.

Backlash in a booming economy

In our model, a populist backlash occurs when the economy is strong because that is when inequality is high. The model helps us understand why the backlash is occurring now, as the US economy is booming. The economy is going through one of its longest macroeconomic expansions ever, having been growing steadily for almost a decade since the 2008 crisis.

This study relates to our prior work at the intersection of finance and political economy. Here, we exploit the cross-sectional variation in risk aversion, whereas in our 2017 paper, we analyse its time variation (Pastor and Veronesi 2017). In the latter model, time-varying risk aversion generates political cycles in which Democrats and Republicans alternate in power, with higher stock returns under Democrats. Our previous work also explores links between risk aversion and inequality (Pastor and Veronesi 2016).

Conclusions

We highlight the fragility of globalization in a democratic society that values equality. In our model, a pushback against globalization arises as a rational voter response. When a country grows rich enough, it becomes willing to sacrifice consumption in exchange for a more equal society. Redistribution is of limited value in our frictionless, complete-markets model. Our formal model supports the narrative of Rodrik (1997, 2000), who argues that we cannot have all three of global economic integration, the nation state, and democratic politics.

If policymakers want to save globalization, they need to make the world look different from our model. One attractive policy option is to improve the financial systems of less-developed countries. Smaller cross-country differences in financial development would mitigate the uneven effects of cross-border risk sharing. More balanced global risk sharing would result in lower current account deficits and, eventually, lower inequality in the rich world.

See original post for references

“rising inequality is a natural consequence of economic growth. ” For which definition of growth? Or maybe, observing that cancer is the very model of growth, for any definition?

Nice model and graphs, though.

What kind of political economy is to be discerned, and how is one to effectuate it with systems that would have to be so very different to have a prayer of providing lasting homeostatic functions?

And what happens in a world where, due to depleted resources, growth is no longer an option and we start living in a world of slow contraction?

Starvation pain and death absent some kind of (fair) rationing mechanisms.

Actually, I can hardly wait. If nothing else will get folks motivated to effect change – this could (let’s hope).

The global overclass can hardly wait too. They think they are in position to guide the change to their desired outcome. Targeted applied Jackpot Engineering, you know.

hoping for an alpha test tube environment or better soma in my next go round?

Oh, I thought they were going to hide in NZ. Although, it is true that revolutions are always unpredictable.

Frase’s “Quadrant IV” – Hierarchy + Scarcity = Exterminism (see “Four Futures”)

At some point if the majority dont think they get any benefit from the economy, they will put a stake through it, and replace it with some thing that works?now that could be some thing very different, but it will happen

I had the same thought – growth as defined in the current, neoliberal model. There is nothing inevitable about inequality – it is caused by political choices.

This article looks good on the surface but as we all know…statistics are often manipulated …this brings into question the information in this article. Where are the studies of what kinds of media people are absorbing to make decisions about voting? How about trying to determine the ethics of those who voted populist in stead of assuming everyone who voted for Trump are down and out? Also information about where and how the data were gathered is needed. The premis that “uneducated” people vote populist is somewhat insulting to those with high levels of education AND THE WILL to do extensive amounts of research before voting. I am over educated and voted “populist” for reasons that are not self-centered. People who are highly informed wee tired of the status quo…as I have said many times…Pulling anyone off the street and cleaning them up for Tv appearances whole have been a better choice than the status quo. We were so desperate for the change that was promised by SN-Obama that we were willing to take any risk.

It is painful to find these assumptions accepted at NC.

“the economy is strong”

Not from my perspective. Or from the perspectives of the work force or the industrial base replacing themselves. Or the perspective of a 4 to 5 trillion dollar shortfall in infrastructure funding.

“In our model, rising inequality is a natural consequence of economic growth.”

Well, that simply did not happen 1946 to 1971.

“populist delivers lower consumption but also lower inequality to US agents.”

REALLY? Consumption of WHAT? Designer handbags and jeans? What about consumption of mass public transit and health care services? I’m very confident that a populist government that found a way to put a muzzle on Wall Street and the banksters would increase consumption of things I prefer while also lessening inequality.

Reading through this summary of modeling, it occurred to me that the operative variable was not inequality so much as “high financial development.”

Agreed, BS but likely to be skewered as the comment section picks up steam.

There’s a lot of skeptics lurking here.

Thanks for pointing out the weaknesses in the article.

Posting doesn’t apply “acceptance” at NC. I think that has been made pretty darn clear on a number of occasions.

Yes and also, let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water. These days, just saying that globalisation leads to inequality and people act rationally, when they push back – even though choices are limited – is pretty revolutionary. We need other analyses along those lines, maybe with a few corrections. Thanks for posting!

“Redistribution is of limited value in our frictionless, complete-markets model”

That’s nice. But in what universe do these “frictionless, complete-markets” actually exist?

“…In our model, a populist backlash occurs when the economy is strong because that is when inequality is high. …”

Yes to the above comments. This sentence really stuck in my throat. A strong economy to me is one that achieves balanced equality. Somehow this article avoids the manner in which the current economy became “strong”. Perhaps a better word is “corrupt”. (No ‘perhaps’ really; I’m just being polite.)

Otherwise some good points being made here.

I also didn’t like that the anti-neoliberalists are being portrayed as not having sympathy for the poor. Gosh, we are a hard-hearted lot, only interested in our own come-uppance and risk-adversity.

Isn’t equality just a value?

A “strong” economy is one that is growing as measured by GDP – full stop. Inequality looks to me like a feature of our global economic value system, not a bug.

Inequality is a problem of distribution. Is a strong economy one that provides the most to a few or a fair share to the many?

High GDP growth could reflect either but which is most important?

If your neighbor is out of work it looks like a recession, if you’re out of work it feels like a depression.

Friction-less Markets exist in where there is much lube.

Trump is probably an expert in that area.

This is complete BS. So is your model.

A universe with spherical consumers of uniform size and density.

Economics is like physics, or wants to be. If you want practicality, you need something more like engineering.

Economics: The Science of Explaining Tomorrow why the predictions you made yesterday didn’t come true today.

I only read these articles to see what the enemy is thinking. The vast majority of economists are nothing more than cheerleaders for capitalism. I imagine anybody who strays too far from neoliberal orthodoxy is ignored.

This post is specifically about globalization, and it is true that anti-globlization measures like tariffs will make all sorts of things consumed by the middle and lower class more expensive, from beer (in aluminum cans) to cars. Marshall Auerback pointed out that if Trump wins his trade war, the price will be higher inflation. That will hit households who spend all or nearly all of their incomes the hardest.

Yes, but what happens to wages under those same assumptions?

The change in wages and other sources of income will be determined by power.

the Trump/Brexit populist thinking has nothing to do with equality. it has do do with who should get preferential treatment and why—it’s about drawing a tight circle on who get’s to be considered “equal”.

not sure how you can pull a desire for equality from this (except through statistics, which can be used to “prove” anything).

I’m confused – so the evidence of statistics should be discounted, in favor of more persuasive evidence? Consisting of… your own authoritative statements about the motives of other people?

In the future, please try to think about what sorts of arguments are likely to be persuasive to people who don’t already agree with you.

A “heterogeneous-agent equilibrium model” whose agents have “inequality aversion” and a world where

greater risks receive and implicitly deserve greater returns to reward the risk taking is not statistics. I trust the evidence of Patrick’s “authoritative statements about the motives of other people” more than I would trust the results inferred from this model and about as much as I trust GDP and government unemployment statistics. For sociology I look to sociologists not economists. For explanations of voter rationales I think surveys asking voters what their rationale for voting was might be more authoritative than a “heterogeneous-agent equilibrium model”.

Wrong. Surveys are exactly statistical bs. A model is a set of equations and parameters that can be precisely compared with measurements and regimes.

This method of picking a model and testing it is abduction and is the scientific method for uninvertable systems that can’t be inducted or deducted. Ask Pierce.

We’ve known that just asking people is bs know for more than a century. Ask Marx, Freud, Bernard.

That is not correct. I’ve done survey research. A well designed and properly validated survey instrument does produce useful results. The Harvard Bankruptcy study, which was a phenomenally well designed piece of social sciences research and served as the foundation for Elizabeth Warren’s book, The Two Income Trap, used survey research as one of its major sources of evidence. This sort of knee jerk black and white claim discredits you.

In the Trump/neoliberal world we get what we “deserve”. Or do we deserve what we get?

The majority of the population believes the losers didn’t try hard enough.

In a world full of Einsteins the bottom 20% would still live in poverty. Life is graded on a curve.

Yes and most people are unaware that the curve is actively managed, in large part by the Fed through interest rates.

If you consider yourself an “environmentalist,” then you have to be against globalization.

(From the easiest to universally agree upon) the multi-continental supply chain for everything from tube socks to cobalt to frozen fish is unsustainable, barring Star Trek-type transport tech breakthroughs.

(to the less easily to universally agree upon) the population of the entire developed (even in the US) would be stablized/falling/barely rising, but for migration.

mass migration-fueled population growth/higher fertility rates of migrants in the developed world and increased resource footprint is bad for both the developed world and developing world.

The long, narrow, and manifold supply lines which characterize our present systems of globalization make the world much more fragile. The supply chains are fraught with single points of systemic failure. At the same time Climate Disruption increases the risk that a disaster can affect these single points of failure. I fear that the level of instability in the world systems is approaching the point where multiple local disasters could have catastrophic effects at a scale orders of magnitude greater than the scale of the triggering events — like the Mr. Science demonstration of a chain-reaction where he tosses a single ping pong ball into a room full of mousetraps set with ping pong balls. You have to be against globalization if you’re against instability.

The entire system of globalization is completely dependent on a continuous supply of cheap fuel to power the ships, trains, and trucks moving goods around the world. That supply of cheap fuel has its own fragile supply lines upon which the very life of our great cities depends. Little food is grown where the most food is eaten — this reflects the distributed nature of our supply chains greatly fostered by globalization.

Globalization increases the power and control Corporate Cartels have over their workers. It further increases the power large firms have over smaller firms as the costs and complexities of globalized trade constitute a relatively larger overhead for smaller firms. Small producers of goods find themselves flooded with cheaper foreign knock-offs and counterfeits of any of their designs that find a place in the market. It adds uncertainty and risk to employment and small ventures. Globalization magnifies the power of the very large and very rich over producers and consumers.

I believe the so-called populist voters and their backlash in a “booming” economy are small indications of a broad unrest growing much faster than our “booming” economies. That unrest is one more risk to add to the growing list of risks to an increasingly fragile system. The world is configured for a collapse that will be unprecedented in its speed and scope.

Excellent summary that. There are so many failure points built into this set-up, particularity with just-in-time delivery systems, that a bad series of storms could play havoc on a global scale as delivery systems are disrupted.

Actually, the way I see it – if one considers oneself an environmentalist, one has to be against capitalism, not just globalization. Capitalism is built on constant growth – but on a planet, with limited resources, that simply cannot work. Not long term… unless we’re prepared to dig up and/or pave over everything. Only very limited-scale, mom-and-pop kind of capitalism can try to work long term – but the problem is, it would not stay that way… because greed gets in the way every time and there’s no limiting greed. (Greed as a concept was limited in the socialist system – but some folks did not like that.)

“Capitalism is built on constant growth.” I have a ‘brand new’ view of photosynthesis. Those plants (pun intended) are ‘capitalist pigweeds’

Until the wind blows them over. Or they dry up… Most plants do not consume exponentially increasing amount of resources. And the resources they do consume they do over a long period of time. You can rest easy – is not quite the same thing.

> re: tagyoureit

“Capitalism is built on constant growth.” I have a ‘brand new’ view of photosynthesis. Those plants (pun intended) are ‘capitalist pigweeds’

Perhaps you need to look for evidence of plants increasing their world wide biomass to have an equivalent case to capitalism’s quest for constant growth?

With deforestation, trees are shrinking their world wide biomass,.

Kelp is disappearing off the California Coast.

https://www.pressdemocrat.com/news/5487602-181/collapse-of-kelp-forest-imperils

Where are your plants that are increasing their biomass footprint in the world?

It could be very good to encourage these plants, as they will be pulling CO2 out of the atmosphere and fixing it in their biomass for a time.

This is very good news, please tell more.

Trouble with Brexit is that the argument is that the UK should trade less with Europe and more with countries like Australia.

The paper posits:

” Given their low risk aversion, US agents insure the agents of the rest of the world by holding aggressive and disperse portfolio positions.”

That low risk aversion could be driven by the willingness of the US government to provide military/diplomatic/trade assistance to US businesses around the word. The risk inherent in moving factories, doing resource extraction and conducting business overseas is always there, but if one’s government lessens the risk via force projection and control of local governments, a US agent could appear to be “less risk averse” because the US taxpayer has “got their back”.

This paper closes with

“If policymakers want to save globalization, they need to make the world look different from our model. One attractive policy option is to improve the financial systems of less-developed countries. Smaller cross-country differences in financial development would mitigate the uneven effects of cross-border risk sharing. More balanced global risk sharing would result in lower current account deficits and, eventually, lower inequality in the rich world.”

Ah yes, to EVENTUALLY lower inequality, the USA needs to “improve the financial systems of less-well developed countries”

Perhaps the USA needs to improve its OWN financial system first?

Paul Woolley has suggested, the US and UK financial systems are 2 to 3 times they should be.

And the USA’s various financial industry driven bubbles, the ZIRP rescue of the financial industry, and mortgage security fraud seem all connected back to the USA financial industry.

Inequality did not improve in the aftermath of these events as the USA helped preserve the elite class.

Maybe the authors have overlooked a massive home field opportunity?

That being that the USA should consider “improving” its own financial system to help inequality.

In my model, eventually, we are all equally dead.

I’m glad to see that issues and views discussed pretty regularly here in more or less understandable English have been translated into Academese. Being a high risk averse plebe, who will not starve for lack of trade with China, but may have to pay a bit more for strawberries for lack of cheap immigrant labor, I count myself among the redistributionist economic nationalists.

I suspect strawberries would be grown elsewhere than the U.S., without cheap immigrant labor (unless picking them is somehow able to be automated).

Yes, it’s called u-pickum @ home ..

Right now I’m making raisins from the grapes harvested here at home .. enough to last for a year, or maybe two. Sure, it’s laborous to some extent, but the supply chain is very short .. the cost, compared to buying the same amount at retait rates, is minuscule, and they’re as ‘organic’ as can be. The point I’m trying to make is that wth some personal effort, we can all live lighter, live slower, and be, for the most part, contented.

Might as well step into collapse, gracefully, and avoid the rush, as per J. M. Greer’s mantra.

I agree with your way of life. Unfortunately I have come to the simple conclusion “nothing” will change until a major global catastrophe hits humanity up the side of the head, like the proverbial, 2X4 up the side of the head of a jack-ass. A “global heart attack” might do it. A good start would be smashing the over-arching banking system; fractionalization into more local controls. Stop the over-paving of some of our most productive agricultural soils just to move masses of limited resource sucking vehicles and useless shopping malls. Either we have better vision for our future or we will surely perish by our own hands or by the Earth itself rejecting our “growth” semblance to a deadly cancer.

The UK had become somewhat dependent on Switzerland for wristwatches prior to WW2, and all of the sudden France falls and that’s all she wrote for imports.

Must’ve been a mad scramble to resurrect the business, or outsource elsewhere.

My wife and I were talking about what would happen if say the reign of error pushes us into war with China, and thanks to our just in time way of life, the goods on the shelves of most every retailer, would be plundered by consumers, and maybe they could be restocked a few times, but that’s it.

Now, that would shock us to our core consumerism.

People might actually start learning how to fix stuff again, and value things that can be fixed.

I recently purchased a cabinet/shelf for 20 tubmans, from a repurposing/recycling business, and, after putting a couple of hundred moar tubmans into it .. some of which included recycled latex paints and hardware .. transformed it into a fabulous stand-alone kitchen storage unit. If I were to purchase such at retail, it would most likely go for close to $800- $1000.00 easy !!

With care, this ‘renewed’ polecat heirloom will certainly outlive it’s recreator, and pass on for generations henceforth.

I thought a Tubman was a double sawbuck, or at least a Hamilton. Otherwise, you’re doing it right kid.

Opps .. yes, should have typed-in ‘1’ tubman …

President Trump announced in Sept of 2018 that September is national preparedness month. In October 2018 President Trump ran a test of the emergency system…perhaps the president, who has the highest security clearances in the world, knows something we don’t?

Oh well, Canada not on any of the charts. Again. We are most certainly chopped moose liver. Wonder what the selection criteria were?

Yes, thank goodness there was no mention of Canada’s failure to negotiate a trade treaty with our best friend. All of a sudden, Canadians seem to be the target of a lot of ill will in other articles.

I think it’s just ill- informed jealousy. Us US mopes think Canadians are much better off than we Yanks, health care and such. You who live there have your own insights, of course. Trudeau and the Ford family and tar sands and other bits.

And some of us are peeved that you don’t want us migrating to take advantage of your more beneficent milieu.

It’s a different vibe up over, their housing bubble crested and is sinking, as the road to HELOC was played with the best intentions even more furiously than here in the heat of the bubble.

Can Canada bail itself out as we did in the aftermath, and keep the charade going?

Do they have a sovereign currency, and as yet not exhausted real world extractable resources?

And I guess by “Canada” you are talking about the elite and the FIRE, right? “There are many Canadas…” https://www.youtube.com/user/RedGreenTV

By Canada, I mean everyone, my family, our PM’s family, the indigenous families, the rich, the poor, the immigrants, the refugees, etc. I do not see “many Canadas” because we started out with two main languages (there are actually many, many languages amongst the indigenous peoples) and we have many cultures and I’m proud that we have these different aspects to our one Canada. I worry, however, that the larger the population becomes the more difficult it will be to have the coherence that we enjoy now. In the meantime, I revel in the Canada that we now are.

Feel free to fill out that 8 inch high pile of Canadian immigration documentation, so ya’all can come on up and join the party. Or just jump on your pony and ride North into the Land of the Grandmother. Trudeau wants more people and has failed to offer proper sacrifice to the god Terminus, the god of borders, so….

Just don’t move to “Van” unless you have a few million to drop on a “reno’ed” crack shack. When the god Pluto crawls back into the earth, the housing bubble will burst, and it’s not going to be pretty.

That’s funny as our dam here is called the Terminus Reservoir, if the name fits…

I’m just looking for an ancestral way out of what might prove to be a messy scene down under, i’d gladly shack up in one of many of my relatives basements if Max Mad breaks out here.

Handwriting’s been on the wall. Canada’s very nice, not perfect, but what place is? And: It’s not the imperial homeland.

Great article, interesting data points, but besides placing tariffs on Chinese imports there is nothing populist about Trump, just empty rhetoric. Highly regressive tax cuts for the wealthy, further deregulation, wanton environmental destruction, extremist right-wing ideologues as judges, a cabinet full of Wall Street finance guys, more boiler-plate Neo-Lib policies as far as I can tell.

I fear Trump and the Brexiters are giving populism a bad name. A functioning democracy should always elect populists. A government of elected officials who do not represent the public will is not really a democracy.

Aversion to inequality thus reflects envy of the economic elites rather than compassion for the poor.

That’s ridiculous. Indeed, the Brexit campaign was all about othering the poor and powerless immigrants, as well as the cultural, artistic, urban and academic elites, never the the moneyed elites, not the 1%. The campaign involved no dicussion what’s so ever of the actual numbers of wealth inequality.

When deciding whether to vote mainstream or populist, US agents face a consumption-inequality trade-off. If elected, the populist delivers lower consumption but also lower inequality to US agents.

How can anyone possibly write such a thing? The multi-trillion tax cut from Donald Trump represents a massive long time rise in inequality. Vis-à-vis Brexit, the entire campaign support for that mad endeavor came from free-trader fundamentalists who want to be free to compete with both hands in the global race-to-the-bottom while the EU is (barely) restraining them.

Trump and Brexit voters truly are irrational turkeys (that’s saying a lot for anyone who’s met an actual turkey) voting for Christmas.

Some of us mopes who voted for Trump did so as a least-bad alternative to HER, just to try to kick the hornet’s nest and get something to fly out: So your judgment is that those folks are “irrational turkeys,” bearing in mind how mindless the Christmas and Thansgiving turkeys have been bred to be?

Better to arm up, get out in the street, and start marching and chanting and ready to confront the militarized police? I’d say, face it: as people here have noted there is a system in place, the “choices” are frauds to distract us every couple of years, and the vectors all point down into some pretty ugly terrain.

Bless those who have stepped off the conveyor, found little places where they can live “autarkically,” more or less, and are waiting out the Ragnarok/Gotterdammerung/Mad Max anomie, hoping not to be spotted by the warbands that will form up and roam the terrain looking for bits of food and fuel and slaves and such. Like one survivalist I spotted recently says as his tag-line, “If you have stuff, you’re a target. If you have knowledge. you have a chance–” this in a youtube video on how to revive a defunct nickel-cadmium drill battery by zapping it with a stick welder. (It works, by the way.)He’s a chain smoker and his BMI must be close to 100, but he’s got knowledge…

The papers’s framing of the issues is curious: the populace has ‘envy’ of the well-off; and populism (read envy) rises when the economy is strong and inequality rises (read where’s my yaht?).

The paper lacks acknowledgement of the corruption, fraud, and rigging of policy that rises when an overly financialized economy is ‘good.’ This contributes to inequality. Inequality is not just unequal, but extremely disproportionate distributions which cause real suffering and impoverishment of the producers. It follows (but not to the writer of this paper) that the citizens take offense at and objection to the disproprtionate takings of some and the meager receipts of the many. It’s this that contributes to populism.

And the kicker: to save globalization, let’s financialize the less developed economies to mitigate cross-border inequalities. Huh? Was not the discussion about developed nations’ voters to rising inequality in face of globalization? The problem is not cross-border ‘envy.’ It’s globalization instrinsically and how it is gamed.

Short version: It’s the looting, stupid.

Agreed.

I’m with Olga. It’s good to see that voting “wrong” taken seriously, and seen as economically rational. Opposing globalization makes sense, even in the idiosyncratic usage of economics.

The trouble, of course, is that the world of economics is not the world we live in.

Why does the immigrant cross the border? Is it only for “pecuniary interests,” only for the money? Then why do so many send most of it back across the border, in remittances?

If people in poor countries aren’t willing to sacrifice for “luxuries,” like a dignified human life, who was Simon Bolivar, Che Guevara, or more recently, Berta Cáceres?

Seems to be a weakness of economic models in general: it’s inconceivable that people do things for other than pecuniary interests. In the reductionist terms of natural science, we’re social primates, not mechanical information engines.

If this model were a back patio cart, like the one I’m building right now, I wouldn’t set my beer on it. Looks like a cart from a distance, though, esp when you’re looking for one.

To the extent that the backlash has irrational aspects in the way it manifests, I would suspect that it relates to the refusal of the self-styled responsible people to participate in opening more rational paths to solutions, or even to acknowledge the existence of a problem. When the allegedly responsible and knowledgeable actors refuse to act, or even see a need to act, it’s hardly surprising that the snake oil vendors grow in influence.

I’m always leery of t-test values being cited without the requisite sample size being noted. You need that to determine effect size. While the slope looks ominously valid for the regression model, effects could be weak and fail to show whether current account deficits are the true source. Financialization seems purposely left out of the model.

Excellent point!

This post starts off with some questionable assumptions — that Donald Trump is protectionist and that Trump’s election and Brexit were about globalization. “In our model, rising inequality is a natural consequence of economic growth.” A ‘natural’ consequence suggests there cannot possibly be economic growth without growing inequality — and yet didn’t the US enjoy economic growth before the 1970s that didn’t lead to inequality, or at any rate lead to much less inequality then today’s ‘growth’ — besides what growth have our economies enjoyed in the last few decades? I view growth measured by GDP figures as about as reliable as employment measured by the government unemployment figures. Isn’t there something called a progressive income tax rate and inheritance taxes that used to take care of some of the inequality.

The author’s demonstration based on a “heterogeneous-agent equilibrium model” makes little hairs on the back of my neck raise up. The agents in this model have “inequality aversion” which “reflects envy of the economic elites rather than compassion for the poor”. I would translate “inequality aversion” into the vernacular as an aversion to getting screwed from behind and the elites are walking off with a lot more than relatively higher consumption. The authors model risk-aversion to incorporate the notion that “less risk-averse agents consume a growing share of total output”. As I recall economists like to assume that those taking greater risks receive and implicitly deserve greater returns to reward their risk taking. That sort of reasoning is used to explain the higher interest rates charged for loans to risky prospects — and finds encapsulation in the old maxim “nothing ventured nothing gained”. What does risk have to do with globalization? “We assume that US agents are less risk-averse than rest-of-the-world agents, capturing the idea that the US is more financially developed than the rest of the world.” — That is an interesting assumption. More “developed” makes financialization sound like a an advanced good thing. I wonder what sort of risk a Cartel makes when it move jobs and capital overseas while controlling local markets and setting its own prices. As one of those risk-averse losers envious of the elite I think I envy the kind of risks they take compared to the risks the lumpen are forced to take like long-term unemployment, homelessness, illnesses, hunger, debt …

Enough. Skipping down to the conclusion: globalization has fragility in a democratic society that values equality. I would draw a different conclusion from this conclusion: Economists should not be allowed to practice sociology and should be held at long arms length from political philosophy.

This post was about globalization and the votes for Donald Trump. Trump opposed the TPP and similar deals along with NAFTA. The TPP and NAFTA are about much more than globalization of trade. I believe they were crass attempts to globalize Corporate power. Free trade was incidental. And what exactly is a populist or a progressive? I thought populists fought the RailRoads in the 1890s and progressives backed Wilson because he kept us out of the Great War. I’m not sure either label fits the voters that no longer fit in either party and represent the decisive swing vote.

The comments here are mad. They focus on the semantics of how things are said rather than the substance of the model.

The simple model is that as consumption of consumer goods grow some players can afford more risk and so their wealth grows faster. Thus inequality increases leading to social conflict over power that can be democratically constrained.

The interesting point is that that is combined with importing inequality via financial vehicles. The risky players import risk from poor players outside the country and that inequality can not be democratically constrained – there’s no global democracy only finance and war.

Thus one solution is to bring the mother down in the most advanced countries.

The emotion-laden connotations are irrelevant – whether they use childish tantrum words like envy, growth or whatever – only the model matters.

The problem is the model has no time, no internal dynamics, no high order terms – in fact it can’t predict whether this will take infinitely long or be dissipated in frictional terms. Or suddenly explode – I can’t really test a model this approximate.

How do these changes get transmitted? It’s a single scale equilibrium model.

I’m disappointed that economic models are still this primitive. They don’t tell me anything more than the Maxist models of 150 years ago. At least those had some internal dynamics.

You suggest that the “focus on semantics” in the mad comments here ignores the substance of the model. This seems odd to me. The variables and assumptions used in constructing the model — what you seem to be referring to as “semantics” — are what give meaning to the outputs from the model. The “emotion-laden connotations” are quite relevant to the way the outputs from the model serve the rhetoric of the model’s designer. The model elaborately computes that US is a very unequal society and predicts the “populist” backlash … but along the way this model has us assume a lot of loaded baggage:

there cannot be economic growth without growing inequality [which begs the question that we need growth] — “less risk-averse agents receive a growing share of total output” — try playing poker using that assumption — “We assume that US agents are less risk-averse than rest-of-the-world agents, capturing the idea that the US is more financially developed than the rest of the world.” — equality is like a luxury good — populist voters are risk averse losers envious of the elite winners …

“Our model predicts that support for populism should be stronger in countries that are more financially developed, more unequal, and running current account deficits.” How did “running current account deficits” get in there? Is that something I should conclude from the assertion: “After a move to autarky, US agents can no longer borrow from the rest of the world to finance their excess consumption.” ???

“Global risk sharing exacerbates US inequality. Given their low risk aversion, US agents insure the agents of the rest of the world by holding aggressive and disperse portfolio positions. The agents holding the most aggressive positions benefit disproportionately from global growth. The resulting inequality leads some US voters, those who feel left behind by globalization, to vote populist.”

Is the US chiefly a buyer or seller risk? I thought the US sold crappy financial assemblages as “AAA” bonds to the rest of the world in the first Great Recession. The mention of “aggressive and disperse portfolio positions” seems strange in aggressive suggests “risky but potentially higher gain” and

I thought positions are dispersed to spread and in theory reduce risk.

I’m not sure how you can conclude that “… the model has no time, no internal dynamics, no high order terms …” I don’t think it does — but I didn’t see anything detailing the implementation of this model here or on its originating site.

But that’s precisely how you play poker! If you have a much larger buy-in, you don’t have to play well — you can just play semi-randomly until your opponents run out of money.

That is the secret of capitalism — that if you have more capital, you can play risky, and wait for the big win that drives out your competitors. I still think the loaded language is just BS — it’s an interpretation of variables that doesn’t really tell us much about the model, and mostly about the religion of the researchers.

“I thought the US sold crappy financial assemblages as “AAA” bonds to the rest of the world in the first Great Recession.”

Really good point, which really undermines the model at this time frame. If the real capitalist winners which are democracies basically reduce to Germany, then you’d expect the inequality to grow their and the backlash to happen there. And that is actually slower in Germany — why? Maybe those dynamics are more important than the rest of the model. Say, Germans are made of a bit tougher stuff than US-Americans, for example.

“I’m not sure how you can conclude that “… the model has no time, no internal dynamics, no high order terms …” I don’t think it does — but I didn’t see anything detailing the implementation of this model here or on its originating site.”

If they don’t specify it, it doesn’t have it. You can always conclude that with researchers — if they had it, they would show it.

The problems of globalisation came out of its economics.

Neoclassical economics was the basis for the neoliberal ideology.

Neoliberalism was a logical step from neoclassical economics.

Neoclassical economics wasn’t a logical step from classical economics.

Economics, the time line:

Classical economics – observations and deductions from the world of small state, unregulated capitalism around them

Neoclassical economics – Where did that come from?

Keynesian economics – observations, deductions and fixes for the problems of neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics – What are they doing?

Economics was always far too dangerous to be allowed to reveal the truth about the economy.

The Classical economist, Adam Smith, observed the world of small state, unregulated capitalism around him.

“The labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

How does this tie in with the trickledown view we have today?

Somehow everything has been turned upside down.

The workers that did the work to produce the surplus lived a bare subsistence existence.

Those with land and money used it to live a life of luxury and leisure.

The bankers (usurers) created money out of nothing and charged interest on it. The bankers got rich, and everyone else got into debt and over time lost what they had through defaults on loans, and repossession of assets.

Capitalism had two sides, the productive side where people earned their income and the parasitic side where the rentiers lived off unearned income. The Classical Economists had shown that most at the top of society were just parasites feeding off the productive activity of everyone else.

Economics was always far too dangerous to be allowed to reveal the truth about the economy.

How can we protect those powerful vested interests at the top of society?

The early neoclassical economists hid the problems of rentier activity in the economy by removing the difference between “earned” and “unearned” income and they conflated “land” with “capital”. They took the focus off the cost of living that had been so important to the Classical Economists to hide the effects of rentier activity in the economy.

The landowners, landlords and usurers were now just productive members of society again.

It they left banks and debt out of economics no one would know the bankers created the money supply out of nothing. Otherwise, everyone would see how dangerous it was to let bankers do what they wanted if they knew the bankers created the money supply through their loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Identifying the source of the problem.

The University of Chicago forgot what they used to know.

Henry Simons was a firm believer in free markets, which is why he was at the University of Chicago.

Having experienced 1929 and the Great Depression, he knew that the only way market valuations would mean anything would be if the bankers couldn’t inflate the markets by creating money through loans.

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher supported the Chicago Plan to take away the bankers ability to create money, so that free market valuations could have some meaning.

The real world and free market, neoclassical economics would then tie up.

What is real wealth?

In the 1930s, they pondered over where all that wealth had gone to in 1929 and realised inflating asset prices doesn’t create real wealth, they came up with the GDP measure to track real wealth creation in the economy.

The transfer of existing assets, like stocks and real estate, doesn’t create real wealth and therefore does not add to GDP.

The real wealth in the economy is measured by GDP.

Inflated asset prices aren’t real wealth, and this can disappear almost over-night, as it did in 1929 and 2008.

https://cdn.opendemocracy.net/neweconomics/wp-content/uploads/sites/5/2017/04/Screen-Shot-2017-04-21-at-13.52.41.png

1929 – Inflating the US stock market with debt (margin lending)

2008 – Inflating the US real estate market with debt (mortgage lending)

Bankers inflating asset prices with the money they create from loans.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Markets need to kept free of the money bankers create from loans.

Then you get the price discovery of neoclassical economics.

Henry Simons and Irving Fisher knew that in the 1930s.

For me the most disturbing part of the paper is the presumption that rising inequality is a consequence of globalisation alone. This is certainly what populists / nationalists believe and would like to persuade us of. Yet, as this blog keeps pointing out, it appears that domestic policies are as much, if not more, to blame. Globalisation did not cause tax breaks for stock options for executives!

Take away that assumption and the paper doesn’t seem to show much. To me it says that globalisation causes inequality, people don’t like inequality and if inequality get bad they vote for people who will stop the thing they attribute as the cause. Hardly profound. But if other things are the cause of inequality, then why the rise of populism?

We are supposed to be rational in the West. There is a riches of inexpensive labor in the East.

Western Labor doesn’t see the advantage of selling itself for less than what it takes to secure food, clothing and shelter in the West.

It is rational.

In the East and in the West labor is at a disadvantage.

The issue I have with this statement is that high inequality leads to lower economic growth.

https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/feb/26/imf-inequality-economic-growth

There is also the matter that a lot of inequality is caused not by productivity, but rather by economic rent seeking by the rich.

I don’t have a very high opinion of the economics school of the University of Chicago (I see it as the class warfare school), but it seems even there, cracks are appearing.