Yves here. I hate to sound like my usual nay-sayer self, but as a young thing, it seemed obvious that that idea that women could have it all, which meant a career and a family, was a myth. I do know women who have done it, but in the majority of those cases, either the wife or the husband has such a high income that they could afford a full time nanny (one woman I know had two). And those women, unlike aristocrats of the past who were perfectly content to fob off children to nannies and governesses, the women who had good nannies often felt the most guilty because their kids seemed to be developing stronger ties to them than to their mother.

But this post also discusses how “employment costs” of motherhood have increased because women spend more time childrearing…and query how much of that extra time is necessarily all that beneficial to the child. I’m thinking of changes like parents being expected to pick up their kids from school rather than letting them walk home and the pervasiveness of “play dates” (which entail parental scheduling and shuttling) as opposed to kids being trusted to organize their own time and get home by a specified hour.

By Ilyana Kuziemko. Professor of Economics, Princeton University, Jessica Pan. Associate Professor of Economics, National University of Singapore, Jenny Shen, PhD student in Economics, Princeton University, and Ebonya Washington, Professor of Economics, Yale University. Originally published at VoxEU

Despite women having surpassed men in earning college degrees, having children later than ever, and accumulating increasing amounts of on-the-job experience, convergence in labour force participation between men and women has stalled. This column argues that one reason for this is women failing to anticipate the effect that children will have on their careers. The findings also suggest that the employment costs of motherhood have risen unexpectedly, and especially so for educated mothers.

Women’s lives have changed drastically over the past century. Women have surpassed men in earning college degrees, and they are having children later than ever, accumulating increasing amounts of on-the-job experience. Yet, since about 1990, convergence in labour force participation between men and women has stalled, even as societies have made progress on workplace gender discrimination (Blau and Kahn 2017). Why has this stalling occurred, especially as women are more prepared for the labour market than ever?

In a new paper, we propose a novel explanation for this phenomenon – that when they are making their key human capital decisions, women do not anticipate the effect that children will have on their careers (Kuziemko et al. 2018). We conclude with some speculations as to why and focus on a key trend – that the employment costs of motherhood have risen unexpectedly, and especially so for educated mothers.

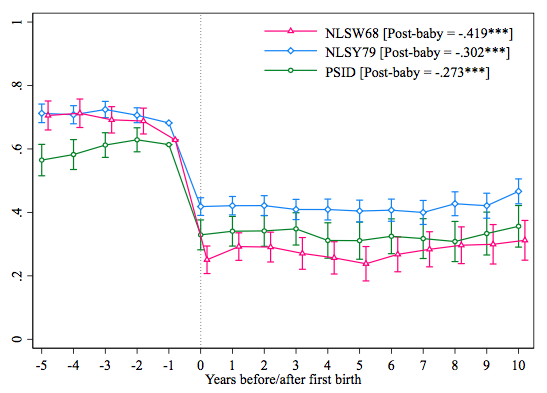

Children continue to pose a considerable cost to careers, and that cost is disproportionately borne by women. Recent studies by Angelov et al. (2016) and Kleven et al. (forthcoming) using rich administrative data from Sweden and Denmark, respectively, provide compelling evidence that women’s careers diverge from that of men’s only after the birth of the first child. Using several nationally representative longitudinal datasets in the US and the UK, we replicate these findings, and estimate that in the five to ten years after birth, women’s employment rates decline by about 25-40 percentage points and show little evidence of recovery relative to the counterfactual no-baby trend (Figure 1 for the US). For men, we find little to no analogous effect.

Figure 1 Event-study analysis of how probability of employment changes after motherhood in the US

Our focus, however, is not primarily on these child penalties, but instead on why women continue to invest so heavily in their human capital development and yet drop out of the labour force at such high rates upon motherhood. We provide several pieces of evidence that suggest a potential role of the lack of anticipation of the career costs of motherhood, both in the short run and in the long run.

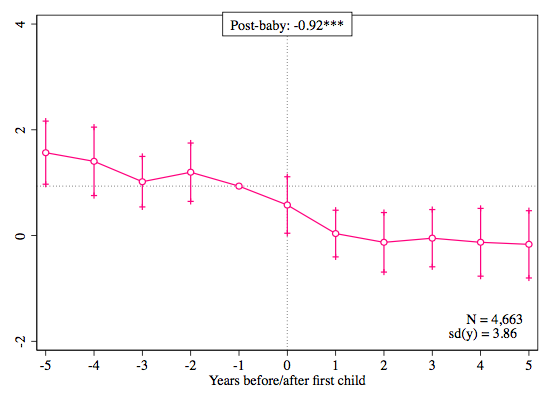

The Surprise

If women are not fully anticipating the employment effects of motherhood, we would expect that the birth of the first child serves as an information shock, causing them to update their beliefs regarding their ability to maintain both family and work commitments. Consistent with this idea, we find that women become more traditional in their attitudes about gender roles regarding work and family after the birth of their first child. For example, after becoming a mother, a woman is more likely to agree with statements such as “A family is harmed when the mother works outside the home,” and disagree with statements such as “Both a husband and a wife should contribute to household income.” Using an index of gender role attitudes that we construct using the available questions in each dataset, we find that women’s attitudes become significantly more ‘anti-work’ in the first two years post-baby and exhibit no recovery in the five years after birth (see Figure 2 for the UK). In fact, in the UK, women’s attitude change post-baby is morethan the average difference in gender-role attitudes between men and women. Interestingly, college-educated women appear most caught off-guard by motherhood, as they experience a larger ‘anti-work’ shift in their views than non-college-educated women. We find little evidence of a significant shift in men’s attitudes.

Figure 2 Event-study analysis of how gender-role attitudes change after motherhood in the UK

More directly related to our hypothesis, we look at survey questions from the PSID that ask parents if they think that parenthood was harder than they expected. Consistent with the finding above that educated women are most surprised and update their beliefs the most, we find that women agree with this statement much more than men, and, moreover, that college-educated women agree much more than non-college-educated women.

Why are college-educated women so caught off guard by the employment costs of motherhood, especially since motherhood is such a common occurrence? We hypothesise that expectations regarding the employment costs of motherhood play a major role – specifically, that women who foresaw a career requiring a college degree were exactly those women who believed that balancing work and raising children would be easier than it turned out to be. We specify a model with this dynamic at play, where women inherit an imperfect prediction of employment costs from their mothers and use this prediction to decide whether or not to attend college. The model shows that women who inherit the lowest predictions of costs attend college, whereas women with the highest predictions do not. Upon motherhood, true employment costs are revealed, and these educated women are negatively surprised by how difficult it is to combine work and family. Our model also demonstrates that our empirical results can only be reconciled by an unexpected increase in the employment costs of motherhood across generations.

The Longer View

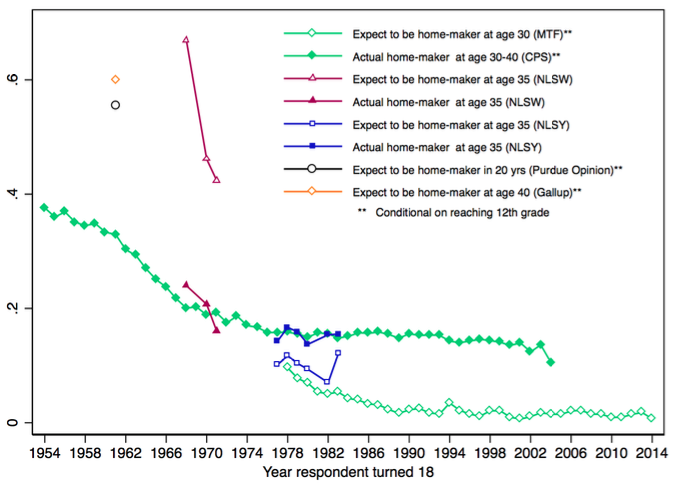

How have expectations about career and family changed over time? To examine longer-run trends in career expectations, we look at what high school seniors thought they would be doing in their 30s and compare these expectations to what their cohorts ultimately did (Figure 3). We focus on high school seniors because they are at an age when they are making key decisions about attending college. As late as 1968, over 60% of female high school seniors expected to be homemakers at age 35. This expectation fell drastically over the ensuing decade, and by 1978, roughly 10% of high school seniors expected to be homemakers at age 30. Today, virtually no girl in her senior year of high school expects to be a homemaker when she turns 30.

Figure 3 Expectations and realizations of future home-making among US high school seniors

When we compare these expectations to reality, however, an interesting trend emerges. Whereas the class of 1968 overestimated the probability that they would be homemakers, the class of 1978 underestimatedthat probability. In particular, while over 60% of girls in the class of 1968 expected to be homemakers at age 35, only about a quarter of them ultimately were. (Note that all outcomes in this graph are plotted according to the year that a woman graduated from high school.) On the other hand, about 10% of the class of 1978 expected to be homemakers at age 30, but ultimately twice as many of them were. Since then, every cohort of graduating seniors has underestimated the likelihood that they would become homemakers.

Why has this reversal in expectations versus reality occurred? We argue that the employment costs of motherhood play a key role and, specifically, that across generations, there has been an unexpectedincrease in these employment costs. Several papers have emphasised the decline of costs of motherhood as a key driver of the rise in female labour force participation over much of the 20thcentury. For example, electrification that led to the widespread adoption of labour-saving household appliances (Greenwood et al. 2005) and medical innovations such as reduced morbidity associated with childbirth and infant formula (Albanesi and Olivetti 2016) enabled women to better reconcile work and family responsibilities, allowing them to enter the labour force in large numbers.

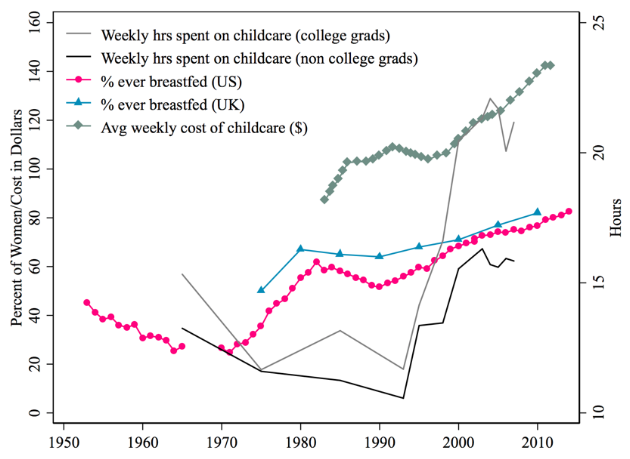

More recent data, however, suggest that these trends may have played out and employment costs of motherhood may, in fact, have risen for more recent cohorts of women. Time-use surveys document that time spent on childcare rose drastically around 1990, and especially so for college-educated mothers (Ramey and Ramey 2010). Figure 4 plots these time-use estimates, as well as other indicators that suggest that the employment costs of motherhood at different child ages have risen for more recent cohorts of new mothers.

Figure 4 Various proxies for ‘employment costs of motherhood’

Childcare costs over the past 50 years have roughly followed a U-shape. For example, breastfeeding rates fell in the 1950s and 1960s (in the US) but then began rising again in the 1970s. Other proxies for employment costs of motherhood, such as the dollar cost of childcare, have also been on the rise in the recent few decades.

Conclusion

Researchers have puzzled over the stalling of the gender gap in labour force participation, especially given concurrent trends that suggest that women have been investing increasingly in human capital accumulation. We propose a novel explanation for this puzzle: that when women are making key decisions about human capital investment, they underestimate just how costly child-rearing will be to their careers. We use several pieces of evidence to provide support for our hypothesis. Most notably, women (but not men) become more ‘anti-work’ in their attitudes about gender norms regarding work and family upon becoming mothers, and educated mothers are most surprised by the employment costs of parenthood. Over the longer run, cohorts of graduating female seniors once overestimated the probability that they would stay at home and raise children, while more recent cohorts of graduating seniors now increasingly underestimate that probability. We provide some speculative evidence that rising costs of childcare, after decades of decline, may be responsible for this lack of anticipation on women’s part. To address the remaining gender gaps in the labour market, there is a pressing need for future work to examine the underlying causes of this apparent increase in the employment costs of motherhood.

See original post for references

Big social problems here, with long-term population effects. Biological reality is that the best time for women to have children is from the ages of 18 – 30 or so. Quicker physical recovery, many fewer birth complications, and fewer birth defects. Sensibly-organized societies recognize this and organize for family continuity on a generational basis – three generations live in a house, the grandmothers and aunts care for the children while the young adults work outside the home. But we as a society so devalue motherhood, probably the most important social function for the health of families, clans, and tribes, that we are actively subverting this critical function in favor of “employment”. Consider the data in the article, which reveals ten percent or less of women expect to be “homemakers” (= full-time mothers) at age 35 – nope, motherhood is for dummies and it’s all about my wonderful career, tra-la!

So many families are in decline because they bought the BS and put their healthy prime reproduction-age women into the workforce while neglecting their most important function – raising the next generation. And, incidentally, devalued the role of men as husbands, fathers, protectors, and providers. Deferring motherhood to older ages, where every effect on the health of the family is bad, in favor of career is a bad idea. Bad ideas have big effects.

I hope you realize that, in a single paragraph, you go from describing this as a societal problem to flippantly blaming women for having careers (tra-la!).

God forbid women be rational actors, right?

Well yes – but the way we are organized makes reproduction an irrational choice. It’s the organization that is bad, not the actor making rational decisions.

Rational actors of X and Y type are the heart and soul of the neoliberal structure. How’s that going to play out, over the long haul? How’s it working out for women currently? Homo economicus is a non-sex-linked creature. Not a very healthy one.

Well it is a societal problem which has its expression in bad ideas that motivate people to to do wrong things when they hold them. I’m not blaming people for their hewing to bad ideas that are fed them 24-7 – but pointing it out. Perhaps I was a bit flippant but people will do foolish things (tra-la) if there are wrong-headed ideologies floating around telling them the foolish thing is a good idea.

My point is that for our society to be sustainable it must reproduce itself. And therefore organizing society for healthy reproduction needs to be job one. Else decline into decadence.

men who know when it’s best for women to have children, sexism same as it ever was. While it might be biologically better, it’s like psychological issues (emotional maturity) don’t matter, nor of course economic ones. But then since women are just breeding machines, why think about such things that almost treat them as actual people. Feminism is the radical notion that women are people as they say.

It is best not to have children too early, and it can be too late.

None of which is Male sexism.

What I was disgusted most with Bill Clinton’s presidency was to use of the term “welfare queen'” for mothers who wished to rase their children, because those using it must have mothers, and the great majority were directly rased by their mothers.

Except those politicians who were hatched by the sun.

It should not be a privilege to stay at hone to raise children, note and ncurr an excruciating financial burden

That also includes the irrational medical cost of birth in the US.

Oh come on. Women can now freeze their eggs, so the issue re older eggs running the risk of producing children who are less healthy has now been removed for women who want to have careers (and therefore have the means to hedge this way). Given high divorce rates, having a career is also a hedge against being divorced (since women just about never come out as well post divorce as they were when married, and the stats support that. Single women, whether never married or divorced, are less well off financially on average than married women).

I was writing about women have the freedom, socially and economically, to make choices.

If freezing eggs for later fertilization be one such freedom, then so be it.

I apologize for my lack of clarity. I do not apologize for my beliefs.

After an admittedly quick read, I don’t see any place where divadab states his/her gender.

I can never understand the purpose of this line of argument. Are you trying to convince me to have kids? Because you’re doing the opposite.

Look at the data: motherhood IS for dummies, in that it’s incredibly burdensome and unrewarded by society. Personally I’ve sought to avoid it for those reasons. You claim it’s important to raise the next generation, but why should I? I’d only get kicked in the teeth if I bothered.

I’d say a better pitch would be to spread those costs more evenly across society – eg via universal daycare, and by making men bear much, much more of the costs than they do now. When you define motherhood as more important than the rest of a woman’s life, you contribute to the problem – to you, the rest of my life isn’t important. Whereas if society could bear to acknowledge that women’s lives have several important dimensions, that could offer a better, less life-ruining trade than the one we’re looking at now.

There are too many people on the planet anyhow, most of all in high resource consuming advanced economies (who also manage to export their pollution to low-regulatory standards countries, mainly China).

And there are many parents who have kids for bad reasons: pressure from parents, peer pressure, fear of not fitting in, sometimes the woman getting pregnant to try to save a failing relationship (note this may not be the first child…). Some of them rise to the occasion and become good parents, but many don’t.

Not everyone needs to be a breeder. But we need breeders and we make it exceedingly hard for people to have a prosperous family life if one of a couple devotes their time to raising children. Raising children is a family matter – IMHO it’s not the State’s role to raise children but rather the State should set the conditions under which families can raise healthy children. Yes the State has a role in educating and socialising children. But there is no substitute for healthy families and communities. A society without children is a sick society.

I don’t use pejorative words like “breeder”. But in a neoliberal society, people are treated as atomized as a condition of working, which is essential for survival unless you are rich (you must sell your labor to get by).

And we need the advanced economy population WAY smaller, like 50% smaller. We are at no risk of not enough women choosing to have kids to have that happen.

True; the Japanese have done the right thing and are now paying a price for it, as is China.

However, I have some concern about who is having children and who is not. If your most responsible and ambitious people choose not to reproduce for long enough, there will be changes in the overall population. Random assortment can carry us for only so long.

I agree that it’s important not to penalize people for having children. It’s now evident that giving women control over their fertility leads to a declining population in any case. As someone said, parenting isn’t easy.

Re: “breeder” – I had no idea this was pejorative. I didn’t mean it pejoratively so please substitute “parent” when reading my comment so as to avoid misinterpretation.

We’re having a rational conversation so I’m a bit hesitant to introduce spiritual concepts and language but I think we have evolved as humans from living deeply infused in the spiritual (which really means feeling something greater than oneself and higher) to living in the material moment of distraction and occupation with the purely material world. IMHO reproduction is sacred, the ultimate expression of love for others. If we understand it (and the world) as purely mechanical we are cutting ourselves off from the essential richness of the living world. We disrespect our living planet to our own peril and poverty.

The world is purely mechanical.

Having kids is the least selfless action a human can take; the urge to reproduce is purely a selfish biological drive.

And we disrespect our planet by…not contributing further to planet killing overpopulation?

Well it’s a values question so it may not persuade. But do other life forms have value? I think so (quite regardless of what lifeforms we may consume to sustain ourselves). So is populating the entire planet with people to the exclusion of all other life forms really that spiritual? Have kids, ok if one must (although the future they are inheriting doesn’t look pretty at all …), but limiting to one makes a lot of sense.

This will no doubt be a unpopular view, but I view having children as one of the cruelest thing people do. Every human religion is based on reconciling people to the inevitability of suffering and death.

Ouch. I prefer thoughtless, narcissist and selfish, possibly power-crazed. “I don’t need any of you! I can make my own people now.”

I dislike this line of reasoning – even if true, this logic can’t be applied 100% or the species would go extinct (maybe you’re okay with that). For the remainder who don’t take the path of shirking, the problem of how to raise children and not bury women in the creche remains. And, in fact, it’s a small minority who remain childless by 40, so the problem is one that most people must overcome.

It’s a straw man to depict anyone advocating for women to be able to have careers and not have children as to having 100% of women not have children. But more important, I am offended by your comment regarding shirking. How women choose to spend their lives is none of your damned business. That is also a personal attack and a violation of our house Policies. You are already in moderation for previous offenses and you’ve crossed the line one too many times.

I apologize for any offense; my use of the word shirking was not meant to be perjorative. As you will see from my other comment in this thread, I am staunchly in favor of women choosing as they please and wish for us all to enable either, any, choice.

Also, it is news to me that I have previously crossed some line. If so, it suggests that I’m just bad at commenting, since I absolutely don’t wish to be a bad citizen, and maybe I should just stick to reading.

My daughter is not having children. As much as I would love a grandchild I told her how sincerely impressed I was that she refused to submit to the social pressure to procreate.

Shamefully not talked about in our cultural norms, but another unhealthy example of children being conceived for completely the wrong reasons — in this instance at the initiation of men — is where a man has left his wife or other long term partner usually, but not always, for a younger model.

All second marriages are inevitably a triumph of hope over experience, but where the previous relationship has involved children, the second wife or long-term relationship partner can end up being “reassured” by the men by means of generating a new “second family”. Thus elevating, in the eyes of the men, the new and inevitably slightly insecure younger woman into an equal and even supposedly superior position to the ex-wife or ex-partner. I don’t know what the women in these situations experiences or typically feels, but I get what the men are trying to do.

It is a recipe for disaster. A second marriage is almost unavoidably more finically challenging for all concerned than a first. And trying to juggle, where custody is shared, as is so often encouraged, the demands of what are usually young adults or early teenagers (from the first relationship) and toddlers or very young children (from the second) — alongside two women as a minimum in the dynamic is an emotional and monetary stressor for anyone. Even a high earner will struggle.

Two men in my age cohort I know have done exactly this. Frankly, even though they’re in the late forties or early fifties, they look at death’s door. One is indebted to the tune of £500k age 49 (they make £100k pa. including bonus) and I have no idea how they plan to clear this by the age of 65. Nor do they, apparently. Financing two households (the “new” one directly and child support to the “old” one) plus Keeping Up With The Joneses middle class trappings (two newish cars on finance eat up £800 a month alone) leave nothing to overpay debts down faster.

The other I know is only slightly less bad. Both are pretty candid that the only reason for the second families was to solidify their new relationships. One also I’m fairly sure did it to “spite” their pervious wife.

The role of men in bringing — I’d stop short of saying “unnecessary” children into the world, that sends the wrong message than the one I’m trying to convey — let’s call it “had for not exactly selfless motives” — children into the world needs a lot more societal honesty.

For second marriages, at least in the U.S., not necessarily a recipe for disaster for men at all. When my ex had a child with his second wife, which he admitted was for her, he was able to reduce child support for his two children from his first marriage, claiming “hardship”. Hardship from a choice he made. I, the first wife, after staying at home with 2 children for 7 years, which was what we both wanted, was told by the courts (and the ex) to get a job—NOW. The judge was sympathetic, but da law is da law. Seven years of marriage entitles the ex wife to nothing but child support, which, as I mentioned, he had reduced. I got no alimony and am not entitled to any social security from the lost years of earnings. I do think, at age 62, the ex is suffering somewhat, but not financially. He is estranged from his only son who resents his lack of attention and is making some noises about reconnecting but so far, too little too late. Divorce is financially catastrophic for mothers, not fathers. I got a lots of stories.

I would add that the choice to divorce was mine. I am bitter about the law, not the divorce.

I didn’t know US Family Courts operated like that. That is shocking. Here, too, the vengeful first wife taking the husband for everything apart from the shirt on their back is a popular media and cultural trope despite a large body of evidence to the contrary https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/mar/19/divorce-women-risk-poverty-children-relationship

Family Courts here are trying to redress the balance, but the deck is inevitably stacked against the woman and children from the first relationship (being deemed older and therefore being able to better support themselves — when the reverse is true in the employment market — and teenage or YA children generally been perceived as less vulnerable than infants and certainly less cute and appealing which unfortunately sways judges despite what the judiciary likes to think).

A stunningly low percentage of single parents receive child support here (37% http://eprints.lincoln.ac.uk/14958/1/Family_structure_report_Lincoln.pdf pg. 44) — the vast majority eligible would be women as they almost always get primary custody and are the primary care givers. The fathers are permitted to make excuses for not doing so, the most common of which is other child rearing responsibilities.

If I was a woman, I’d seriously consider sterilisation. Neither legal nor moral/cultural systems are in your favour.

Sterilization sounds crypto-fascist. I prefer withholding sex, the only thing men really care about. Somebody should write a play about that.

Aristophanes did just that: “Lysistrata.”

“Originally performed in classical Athens in 411 BC, it is a comic account of a woman’s extraordinary mission to end the Peloponnesian War by denying all the men of the land any sex, which was the only thing they truly and deeply desired. Lysistrata persuades the women of Greece to withhold sexual privileges from their husbands and lovers as a means of forcing the men to negotiate peace—a strategy, however, that inflames the battle between the sexes.” — Wikipedia

I know. Sorry, I was being ironic.

@Zona Rosa – I agree completely. The burdens of our modern societal reorganization have fallen much more heavily on women than on men. (I’d argue it’s more like societal destruction, which has also diminished men’s roles and responsibilities while loading women up with difficult choices and heavy burdens). In this sense the religious right is quite correct – it’s about the destruction of family and community in favor of atomised work and consumerism, run by cartels motivated by profit. (And in what ethical system is desire for profit (=greed) considered virtuous?)

I speak from personal experience here. I have a bachelors and a masters degree in Molecular Biology. I worked in a National Laboratory for 10 years. Then I had a child (at age 28). In the field of science, you have to expect 45-50hr weeks, particularly when you are doing a PhD or a post-doc. Most of the women i knew waited until after they got tenure or a good staff position after their post doc (around age 35) to have a child. For me, the first baby concurred with the time when I needed to get a PhD. In order to go farther in science, one was required. My spouse was not able to fill in for me with the baby enough for me to be working 60hrs a week. So i stopped at the masters and took a break from work. I had my second child less than 3 years later, and after 2 more years at home, i started to look around for employment opportunities. I quickly realized that there are NO jobs that are part time, or have less than the 50 hrs per week in my field. I could do that, and then basically never see my children. The part-time jobs are all given to college students (cheap labor). People with PhDs who have worked for many years may be able to swing a flex-time arrangement, but i am not in that position. I also now have a big 6 year gap in my resume. The one job as a lab manager i got an interview for wouldn’t hire me because i was overqualified. So F@%# that. I see no future for myself in my field. I have to start over. I am teaching part time now, and considering doing that full time. But its not what i really want to do. I consider it a sad waste of talent that i cannot work in science. I have years of lab experience that cannot be learned from a book. But our society makes it so i have to completely abandon my children to daycare in order to have a career, and i love them too much to do that. I consider myself EXTREMELY lucky that my husband is able to provide enough for us to live comfortably. Thats my story…

That’s my Mom’s story also. What a waste – except – for my three siblings and I having our Mom around when we were young was of incalculable value.

It used to be that “society” was run by and large by women. My Mom epitomises that – she used to run the local meals on wheels organization and our local youth swim team- all volunteer – and now she is treasurer of a university women’s club that raises money for and distributes scholarships to young women. Not only is this organization providing useful work for older women, but also mentoring opportunities for young women of promise. This is what I mean by “society” – it’s not so much the formal structures but rather the relationships and work that keep the thing going richly and with mutual benefit. And completely outside of the dominant consumer culture that has destroyed much of our society.

We equate money payment with value to our detriment.

I have to disagree that your mother’s volunteer work was “completely outside the dominant consumer culture” . We are all part of the consumer culture. Exalting volunteer work by stay at home moms makes me nervous. In order for your mother to do her volunteer work somebody was supporting her. That is a disabling dependency.

It’s complex, civil society matters in very basic ways, but also the nonprofit industrial complex does support the dominant system, it’s one of it’s support factors. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t do some good.

And sometimes unpaid work supports worker exploitation as it displaces paid labor, which many people need, not want, *need*. It’s probably those in better socioeconomic situations that are allowed to have it as a want for the unpaid parent, and it was ever thus, even if less people have that option now, the lower classes have never had those options.

I might worry less that in order for his mom to do her volunteer work someone was supporting her, as in order for her to do it someone may have been displaced from what could have been paid labor.

Excellent point, thank you.

I heartily disagree. The greatest work of society, that is the communal and sacred, is cheapened by making it a paid function, Imho. It’s a symptom of a sick society that monetises everything, that makes money the only arbiter of value.

Here’s another example – in our town in the seventies we had a bit of a fighting culture develop among the juvenile men – it was getting a bit out of hand with bullying and fights that really became brawls from time to time. SO some of the older men, my Dad included, set up a boxing club run by one of our local police officers. No one was paid – it was all volunteer. This provided an outlet for the aggression in a supervised setting, ensuring it did not get out of hand and teaching responsibility and restraint. ALso recognizing champions, very important to warriors. It’s not about the money. It’s about the greater good of the community.

Thank you for sharing this. I think the article captures something true about mothers not expecting how having children is not the best career move, unless you are willing to transport their upbringing to relatives and strangers. Like you, I couldn’t do this, and this was before I discovered how crappy most daycares are. Years ago Fran Leibowitz remarked that the problem with women and career success is that once women have children “they tend to become very interested in them”. But that’s not okay, mothers are supposed to lean in. Capitalism demands it.

In her prefatory remarks to this post, Yves mentioned something I think is really important and relevant to motherhood: how childhood has changed. When I was a child, my friends and I were constantly being sent outside to play– alone, or with each other. Most kids, including me, walked to school, alone or with friends, from kindergarten on. If it was pouring rain, AND if Dad had not taken the family car to work, Mom might drive my friends and me to school, but that was unusual. My mother taught private piano lessons in our living room after school and on Sat. mornings, so I often spent those times at the home of my best friend, whose mom worked full-time (she was divorced). Sometimes I just went to the library after school. Sometimes I came home and went to my room to read a book; the point is, it was pretty much up to me. One afternoon a week, on a day she wasn’t teaching, my mother ferried me to music lessons, dentist appointments, and so forth. When my daughter came along in the 70’s, her daily routine was similar to the one I had as a child: she walked to school, walked either home or to a daycare mom’s house after school (depending on my part-time work schedule), went to the library, and so forth. I knew where she was, and she knew what time to be home for dinner.

The point is, kids in the 50’s, 60’s, 70’s and 80’s spent a lot of time out of the sight and earshot of our parents. I would not trade that time for the way middle class American children are raised today, constantly under parental oversight. Nor would I want to be the ever-vigilant helicopter mom.

My father has some tales to tell from the 50s/60s. They got shot at stealing watermelons, got sprayed with mosquito pesticide, drove around in grandma’s car at the age of 12, smoked cigarettes, got the **** beaten out of them by bigger kids, swam in the polluted quarry…fun. There was a story recently about a kindergartner that didn’t get picked up by the school bus and walked home…lawsuits ensued. This actually happened to my father in kindergarten, he just walked and got home around dinner time and no fuss occurred. He walked along a big highway and no one thought “hmm weird that a little kid is walking down the highway”.

In the 80’s/90’s we were latchkey kids attending private school (we were not well off – my grandparents must have subsidized). Some days we had to ride the city bus with weirdos and mean big kids. Some days we had to walk to my mother’s office hours or class. And some days we carpooled home with a friend who had a mom that stayed home. Guess which scenario was better.

I chose to stay home for 6 years and now I work part time. I don’t feel like I wasted anything. My work was interesting and financially rewarding but I don’t feel like it did much other than make rich people richer. My family and sanity are more important than a fancier house, nicer car, etc.

I get this is a luxury as my husband can provide, but I completely disdain the idea of “having it all”.

Amen, sister.

The role of men and their indifference to the impact of childcare is unfortunately given short shrift here, when in my estimation this is the crucial problem. It’s simply mathematical fact that as women’s labor force participation increases, men must assume a corresponding share of the childcare burden – but haven’t been, and continue to see it as outside their purview.

In fact this makes little sense – the demands of infancy are intense, but brief. Family sizes are small these days. If infancy were the only childcare hurdle to overcome, women would be able to recover relatively easily and resume their careers. Post-infancy, and especially post-breastfeeding (which many families eschew), there is no difference in the ability of men and women to contribute to childcare other than culture and prejudice.

As the father of a young child, with a wife who currently brings in the vast majority of our collective income, I’m acutely aware of the need to assume, at the least, an equal share in child rearing, if not at times the majority. The failure of men to take up this role can in my estimation only be attributed to societal norms that perceive fatherhood and child-rearing as unmasculine, and reserve “nurturing” as a womanly attribute, while assigning “providing” to men. These attitudes are nonsensical and must be ground away by feminism, especially one that hopes to encourage female participation in work and civic life.

There is also a tendency in these comments to ridicule female workforce participation as selfish or the product of an overbearing capitalism that wishes to milk more labor out of each of us. While these criticisms are not without merit, it is past time to develop a society which allows women to engage fully and assume a hand in the shape of the economy and polity. This *cannot* happen without men taking up the burden of childcare.

I know several men who were primary caregivers to their children. The children are now teens and ‘tweens. In all cases, the fathers have deep and loving relationships with their children. They invested time, emotion and energy into their children and now enjoy close relationships with their children.

Many men complain of just being a “wallet” to their children. They fail to see how they set that dynamic with years of non-involvement (and sometimes disinterest) during their kid’s early childhoods.

You reap what you sow.

I thought this article would be a good compliment to this post.

https://familyinequality.wordpress.com/2012/10/31/womens-economic-dominance-is-it-really-inevitable

Despite prognostications in recent years, women’s economic equality still has a long way to go so much more work needs to be done. I hope NC continues to shine a light on this issue.

A couple of excerpts:

So many people are so attached to this narrative of women’s rapid advance that they haven’t noticed there has been no advance in the last 17 years

The ostensibly gender-neutral processes of economic transformation are not the source of women’s progress they once were

I wonder how inclined millenials are to have children these days, given poor economic prospects and massive debt. It is probably harder now to have a child. Russia experienced a population growth decline in the 1990’s caused by its economic problems.

Legalized prostitution and government-paid child support for parents who choose to stay home with their kids would address two big reasons people enter into (or remain in) bad relationships. Not holding my breath for either one in the U.S.

On a larger scale it seems like a baseline assumption of our economic system is that everyone will normally work full time from age 25 to 65 (plus or minus a few years on either end). This is obviously not a realistic assumption, especially for women, but what are the alternatives?

Subgroup analysis by class/race might shine more light on gender gaps in labor force participation, earnings, etc. I suspect the gaps are mostly confined to the upper two earnings quintiles and that those in the lower quintiles don’t see the gaps in their daily lives nearly as much.

I work at a historically black US college with 70% females. Students are mostly from families earning below median incomes and very few come from the top 20%. By age 34 women grads earn on average about 10% more than men and marriage rates are about 25%. Among all 100+ HBCU’s there is little if any gender-based earnings gap, marriage rates are low and about 1/3 end up two earnings quintiles above their parents. A At my school, average graduate wages are somewhat below the median for the state so very few have an option to exit the workforce to raise children and nobody expects to have this option when seeking a degree. Parents often rely on family to reduce childcare costs, often sacrificing career opportunities to live nearby.

In contrast, at US universities that cater to upper / upper middle class families, male grads earn 30-60% than women by age 34 and marriage rates are closer to 60%. A significant minority of parents earn enough to support an entire family so some spouses have an option to exit the workforce.

Universities with lower family incomes tend to have significantly lower gender gaps. Those catering to the lowest income families have virtually no gender gap.

The NYTimes has a nice site to explore earnings gaps and related statistics for US colleges at https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/college-mobility

BBC did a good audio documentary on a related subject – ivf and how women are using it to postpone having children. https://itunes.apple.com/sg/podcast/the-documentary-podcast/id73802620?mt=2&i=1000419973446

“Event-study analysis of how gender-role attitudes change after motherhood in the UK” – pink line graph.

There’s a problem: women’s attitudes change significantly BEFORE the first birth, or even conception. That may be in anticipation of motherhood, or the result of maturity/experience. But it seriously challenges their thesis, which is that the EXPERIENCE of motherhood sharply changes women’s assessment of their careers. That’s an appealing thesis, but it isn’t supported by those data.

Sigh. Public policy will be a lot more complicated if it turns out that there are irreducible differences between the sexes – not something we know yet. Basic biology is that females have a much greater investment in babies (unless you’re a seahorse). And birth and nursing create an especially strong bond, if they get the chance. (It looks as if that was deliberately prevented by nanny cultures. Some of those people were pretty messed up – see “A Distant Mirror.”)

That said, I tend to focus on policy adjustments to women being in the workforce. This is an example of unfinished business for feminism. Offhand, I see three possible approaches; probably all are called for. The most obvious is parental leave. You’d really want to give both parents a year off – probably first the mother, then the father. Not sure how to handle single parents, mostly mothers. Year and a half? Applying it to both parents should reduce the differential impact.

Almost as obvious: reduce the work week. The fundamental problem is that nobody’s home; a shorter work week would help solve that, as well as unemployment. But it doesn’t apply well to salaried or self-employed people; some creativity is called for (meaning I don’t have a solution.)

Finally, it would be helpful to have a much more relaxed workplace, where bringing children or having them nearby (workplace day cares) is possible. That means fixing the power balance between employers and workers, something that is desirable in itself. A project for unions, if we still had them, perhaps?

No matter how desirable a social change, it will bring new problems in its wake. That’s what we’re dealing with.

“Today, virtually no girl in her senior year of high school expects to be a homemaker when she turns 30.”

Surely that reflects a drastically changed economy, in which two incomes are required for most families, at least as much as attitudes about gender roles. It’s just realism.

Apropos this very topic, thanks to Jerri-Lynn in today’s links:

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/raising-children-when-the-village-has-disappeared/

NC has rightly called attention to the loneliness epidemic, including recently. The issue of motherhood, far from being purely an economic one, is also related to the issue of loneliness. I am surprised that this has not been touched upon in the comments. My SO and I are currently struggling to decide whether to have children or not, the reason being her career. Yes, I am supportive of her and I am not pressing anything. She is 12 years younger than me (no, I did not trade for a younger “model”) so she has time, but being in my early 40’s I feel like I am running out of time. And that’s fine by me because the last thing I want is to even make my SO feel pressured to do something she doesn’t want or is not ready for, but both of us are concerned with the potential to be lonely later in life if we do forego having children. Suffice it to say, I deeply resent the fact that neoliberalism has foisted such difficult decisions on us (humans “us”), and if this is what the new normal will be forevermore, then having a smaller human population is not an answer. Having no human population is. We are hardwired to be social creatures, and even if we are evolving to be less social (something the loneliness epidemic suggests isn’t the case), then I submit that we are being robbed of something of incalculable value, something so essential to what it means to be humans that I see no point to continue to exist as a specie without it. Just my two pennies.

I find how your considerations for having children are the impact on careers and worry that you’ll be lonely in old age very telling, and entirely normal (as in common).

At no point do you consider either the impact on humanity as a whole, or the impact on the children themselves. Industrial civilization is headed for a cliff; the future for any children born now is not likely to be a pleasant one.

So do tell, how do we pick who should procreate? What will be the impact on humanity based on that decision? Do we just roll over and give up just because the future will be trying? Take your self-righteousness and try it on someone else. I have considered all of these things. Those who have been reading my comments over the years will recall that my former SO and I had decided against having children, not in small part due to some of the considerations that you say I disregard. I reserve the right to change my mind as circumstances change, and frankly your attacks on anyone who wants children are contemptible. Who appointed you the arbiter of who, if anyone, should procreate?

What a bizarre non sequitur. Did I say anything about arbitrating who gets to procreate? Ultimately you’re only responsible for your own actions.

You reserve the right to change your mind as circumstances change, okay. So as it becomes increasingly clear the future is going to be a bleak one, you change your mind…to being open to having kids? Great judgement you got going on there…

Do we “roll over”? Strawman; plenty of people are going to keep having kids. The existence of future humans is not remotely dependent on your decision to reproduce. What you decisions will impact, however, is whether one or more individuals have to face a lifetime (which may be very short) in a collapsing world.

You can go ahead and act self-righteous (nice projection by the way) and offended, but my points all stand. Your (potential) children won’t be thanking you fifty years from now as they’re scavaging in the ruins.

What a load of BS. Do visions of a dystopian future give you wet dreams or something? Are you clairvoyant and can tell how my children would feel about their parents? How the f@ck would you know that my children wouldn’t be better-equipped to handle whatever the future holds than someone else’s children? Whatever it is that makes you a bitter hag or a nasty prick or whatever gender-indeterminate creature you may be, step the f@ck back and think hard whether antagonizing people who dare dream of a real future is a productive use of your time. Prophesies of inevitable doom and gloom will not take humankind any place good, and I refuse to live my life in passive resignation that everything is predetermined for us and the following generations. Go spout your bitterness with like-minded cowards. Yes, I changed my mind, but even when I did not want children I never presumed to have the right to judge others and berate them about their choices. If anything, your aggressiveness achieves the exact opposite of what you set out to do. If you are so d@mn miserable and so sure about the miserable future that awaits us, just end it for yourself right now. Why suffer and why waste valuable resources? Most of us would rather enjoy whatever time we have left on this beautiful blue speck, and at least try to ensure that it will be there for the following generations as well.

I can only presume you haven’t been paying much attention to how bad the coming decades are likely to be.

To Pleune’s point, potable water will become a scarce resource by 2050.

The fact that you care about these things probably means you would be great parents. My husband is older than I am and it did limit our family size (probably for the best). If there is one thing that I have learned as a parent, you have to let go of your “expectations” as kids have a way of derailing them! Careers seem to change one way or the other. But again, having it all is not how life works, at least in my experience. Best to you, do what makes you happy.

I have to tell you that I see a lot of kids not doing much for their parents in their old age. My siblings and I try to seem my mother, but she is alone over 3/4 the time. She can’t drive any more and refuses to move into assisted living.

There’s a combination of adult kids not having a lot of time, juggling their own families and careers, and older parents refusing to adapt and/or compromise a bit. You mentioned your mom won’t go into any kind of assisted living.

My parents stubbornly refuse to sell the house that they aren’t able to maintain, physically or financially. It is creating even more loneliness and concomitant bad effects on health. Also, it’s more burden on me, reducing time spent with grandchildren, frequency of visits.

It’s a matter of no one living anywhere near her. I am 5 hours away, door to door. My middle brother has to drive 2 hours to Green Bay and take 2 flights to see her, so over ten hours. My other brother is a 10-11 hour drive away and flights are no faster.

I was a stay at home husband. My wife had degrees and could earn more money easier than I and being a teacher, she had summers off. (I, being mostly a musician and not too good at making the money.) . I had unrealistic expectations of what I could get done at home while watching the kids – at least til they went to school.(what did you do today – “It’s hard to say but I’m tired.”) But being a father was the best thing I’ve done with my life.it did hurt my ability to make money and my career. There are better things than work “If work was all that great, the rich would have stole it all a long time ago.” Am I wrong that I think Yves has no children? And there are definitey no studies that could have been made that prove that young eggs that have been frozen wil produce equally healthy children – even frozen food is not as good as fresh.

This podcast is a great supplement to this article – https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06kvxh2 –

The New World Of Reproduction

The Documentary Podcast

Krupa Padhy examines where we have got to after 40 years of IVF. In England, she visits a family made up of white British parents and their three boys, plus a ‘snow baby’: created during an IVF cycle for her Indian-American genetic parents, but adopted as an embryo by her birth family. She hears from ethicists and law makers from around the world about how countries have struggled to adapt to new technological realities, and discovers stories that challenge ideas of what IVF is for, like that of an Indian woman who used her dead son’s sperm to create grandchildren.