Yves here. It should not be news that inequality imposes a health cost even on the wealthy, including on mental health.

By Tabita Green is a worker-owner at New Digital Cooperative, a digital communications firm based in northeast Iowa, and a new economy advocate. Follow her on Twitter @tabitag. Originally published in the The Mental Health issue of YES! Magazine.

n early June of this year, the back-to-back suicides of celebrities Anthony Bourdain and Kate Spade, coupled with a new report revealing a more than 25 percent rise in U.S. suicides since 2000, prompted—again—a national discussion on suicide prevention, depression, and the need for improved treatment. Some have called for the development of new antidepressants, noting the lack of efficacy in current medical therapies. But developing better drugs buys into the mainstream notion that the collection of human experiences called “mental illness” is primarily physiological in nature, caused by a “broken” brain.

This notion is misguided and distracting at best, deadly at worst. Research has shown that, to the contrary, economic inequality could be a significant contributor to mental illness. Greater disparities in wealth and income are associated with increased status anxiety and stress at all levels of the socioeconomic ladder. In the United States, poverty has a negative impact on children’s development and can contribute to social, emotional, and cognitive impairment. A society designed to meet everyone’s needs could help prevent many of these problems before they start.

To address the dramatic increase in mental and emotional distress in the U.S., we must move beyond a focus on the individual and think of well-being as a social issue. Both the World Health Organization and the United Nations have made statements in the past decade that mental health is a social indicator, requiring “social, as well as individual, solutions.” Indeed, WHO Europe stated in 2009 that “[a] focus on social justice may provide an important corrective to what has been seen as a growing overemphasis on individual pathology.”

The UN’s independent adviser Dainius Pūras reported in 2017 that “mental health policies and services are in crisis—not a crisis of chemical imbalances, but of power imbalances,” and that decision-making is controlled by “biomedical gatekeepers,” whose outdated methods “perpetuate stigma and discrimination.” Our economic system is a fundamental aspect of our social environment, and the side effects of neoliberal capitalism are contributing to mass malaise.

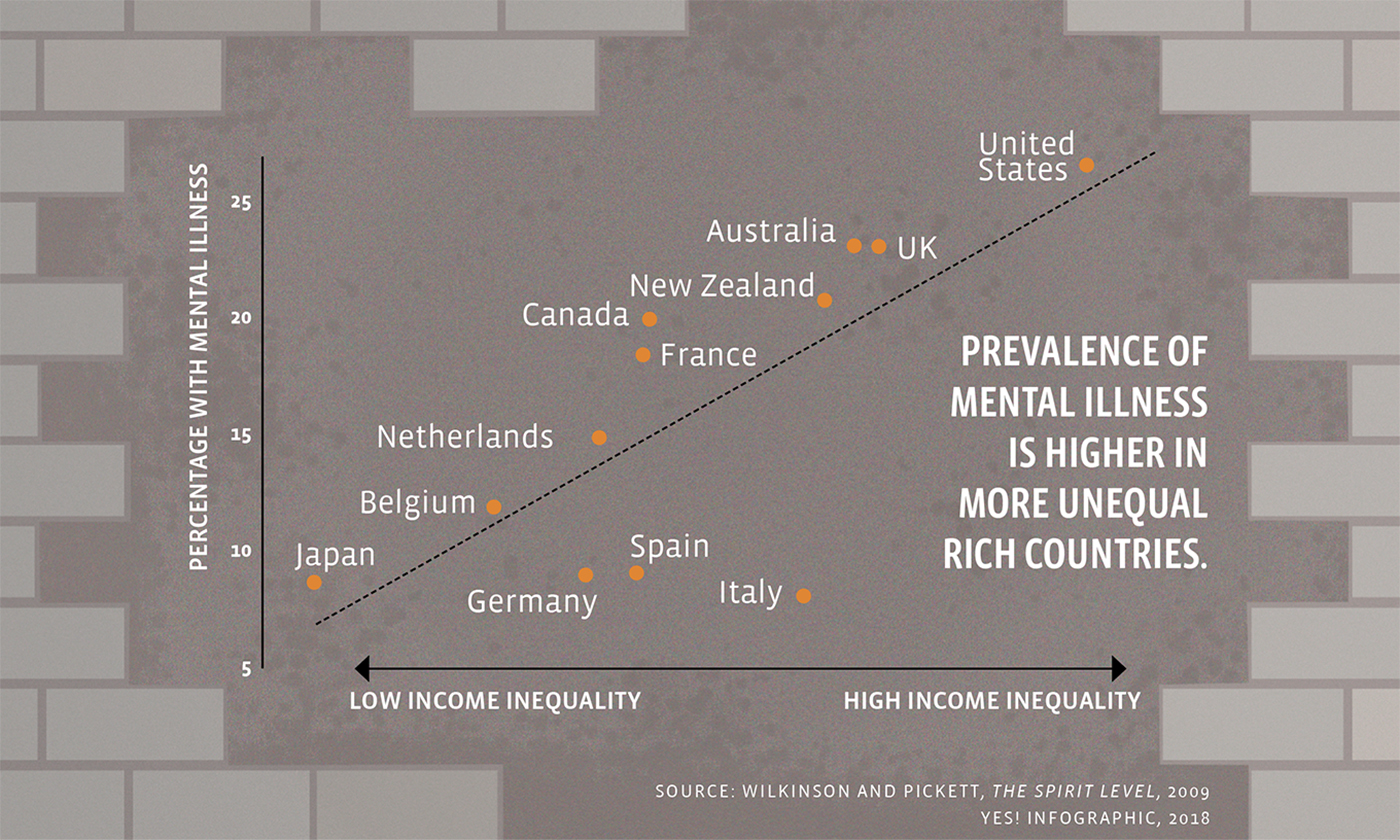

In The Spirit Level, epidemiologists Kate Pickett and Richard G. Wilkinson show a close correlation between income inequality and rates of mental illness in 12 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development member countries. The more unequal the country, the higher the prevalence of mental illness. Of the 12 countries measured on the book’s mental illness scatter chart, the United States sits alone in the top right corner—the most unequal and the most mentally ill.

The seminal Adverse Childhood Experiences Study revealed that repeated childhood trauma results in both physical and mental negative health outcomes in adulthood. Economic hardship is the most common form of childhood trauma in the U.S.—one of the richest countries in the world. And the likelihood of experiencing other forms of childhood trauma—such as living through divorce, death of a parent or guardian, a parent or guardian in prison, various forms of violence, and living with anyone abusing alcohol or drugs—also increases with poverty.

Clearly, many of those suffering mental and emotional distress are actually having a rational response to a sick society and an unjust economy. This revelation doesn’t reduce the suffering, but it completely changes the paradigm of mental health and how we choose to move forward to optimize human well-being.

Instead of focusing only on piecemeal solutions for various forms of social ills, we must consider that the real and lasting solution is a new economy designed for all people, not only for the ruling corporate elite. This new economy must be based on principles and strategies that contribute to human well-being, such as family-friendly policies, meaningful and democratic work, and community wealth-building activities to minimize the widening income gap and reduce poverty.

The seeds of human well-being are sown during pregnancy and the early years of childhood. Research shows that mothers who are able to stay home longer (at least six months) with their infants are less likely to experience depressive symptoms, which contributes to greater familial well-being. Yet in the United States, one-quarter of new mothers return to work within two weeks of giving birth, and only 13 percent of workers have access to paid leave. A new economy would recognize and value the care of children in the same way it values other work, provide options for flexible and part-time work, and, thus, enable parents to spend formative time with their young children—resulting in optimized well-being for the whole family.

In his book Lost Connections, journalist Johann Hari lifts up meaningful work and worker cooperatives as an “unexpected solution” to depression. “We spend most of our waking time working—and 87 percent of us feel either disengaged or enraged by our jobs,” Hari writes.

A lack of control in the workplace is particularly detrimental to workers’ well-being, which is a direct result of our hierarchical, military-influenced way of working in most organizations. Worker cooperatives, a building block of the solidarity economy, extend democracy to the workplace, providing employee ownership and control. When workers participate in the mission and governance of their workplace, it creates meaning, which contributes to greater well-being. While more research is needed, Hari writes, “it seems fair … to assume that a spread of cooperatives would have an antidepressant effect.”

Worker cooperatives also contribute to minimizing income inequality through low employee income ratios and wealth-building through ownership—and can provide a way out of poverty for workers from marginalized groups. In an Upstream podcast interview, activist scholar Jessica Gordon Nembhard says, “We have a racialized capitalist system that believes that only a certain group and number of people should get ahead and that nobody else deserves to … I got excited about co-ops because I saw [them] as a place to start for people who are left behind.”

A concrete example of this is the Cleveland Model, in which a city’s anchor institutions, such as hospitals and universities, commit to purchasing goods and services from local, large-scale worker cooperatives, thus building community wealth and reducing poverty.

The worker cooperative is one of several ways to democratize wealth and create economic justice. The Democracy Collaborative lists dozens of strategies and models to bring wealth back to the people on the website community-wealth.org. The list includes municipal enterprise, community land trusts, reclaiming the commons, impact investing, and local food systems. All these pieces of the new economy puzzle play a role in contributing to economic justice, which is inextricably intertwined with mental and emotional well-being.

In Lost Connections, Hari writes to his suffering teenage self: “You aren’t a machine with broken parts. You are an animal whose needs are not being met.” Mental and emotional distress are the canaries in the coal mine, where the coal mine is our corporate capitalist society. Perhaps if enough people recognize the clear connection between mental and emotional well-being and our socioeconomic environment, we can create a sense of urgency to move beyond corporate capitalism—toward a new economy designed to optimize human well-being and planetary health.

Our lives literally depend on it.

Years ago I was fortunate enough to spend some time on the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua. An older fisherman and I were chatting one evening as the sun set while drinking fresh coconut his son had cut down from a tree. At one point he went off about how the people he meets from America think he has nothing and talk about “money this and money that”. He then looked around and said, “I don’t have much, but I have everything I need”. I looked around at his family, the sunset, the water… took a sip of my coconut, and thought of all the people I know around the US and couldn’t think of anyone as content as the people I was meeting on that trip. Thought about the constant highs and lows, the hustle and the grind to get by day to day, to get ahead yet always feeling one step (or more) behind.

Yeah, I’m still searching for just having what I need.

Money wasn’t an issue in the suicides of Kate Spade & Anthony Bourdain, but something else was lacking, of which we can only speculate.

I feel lucky that my needs are simple for the most part, and the wilderness provides solace, my rock if you will. It’s also the one thing in my life that’s pretty much remained unchanged, in a world bent on change.

And the wilderness doesn’t take Visa, American Express, cash, or any kind of payment for services rendered, such a rarity in a country obsessed with money.

Apparently your wilderness also has WiFi; otherwise I do not know how you maintain your robust commenting regimen.

I’ve been on the D/L for 6 weeks now-a couch potato and I don’t like it, and it looks like another month or so of robust posting will be likely, until I recover.

I enjoy the wilderness in moderation, it’s not something I do all the time, but much more than the regular joe or jane.

This year so far, I have 32 nights sleeping in a hammock in the back of beyond, only a little under 10% of all possible nights, and I apologize for my lack of effort otherwise.

I do not like anecdotes like this. At all.

I have a disorder called GCH1 Deficiency which results in low levels of BH4, and subsequently, low levels of all neurotransmitters.This leads to several mood disorders (anxiety, depression, Schizoaffective) as well as neurological issues:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0165178117317742

Through a complicated process, DHA and EPA from fish increases the enzymes activity (It increases UBE3A which regulates GCH1 if you are interested).

Note that the man in your anecdote was a FISHERMAN.

Just because the research on mood disorders is in the Dark Ages does not mean that mood disorders are not about brain chemistry. I am not talking about changes in brain chemistry that leave you feeling feeling a bit sad or a bit anxious, I am talking about the brain chemistry that makes you want to throw yourself off a bridge or tell people you saw God.

No medication worked for me, and living a “simple, meditative life” did not either. What worked was a fish only diet and low omega 6 and protecting myself from oxidative stressors. If my mood disorders were caused from my upbringing or social stressors alone I could not have ever recovered by diet alone.

So maybe “everything I need” to the fisherman was the fish he was eating and you just went for the simple answer that it was “the simple life”. His simple life was very traditional and he was probably living as his genetics, shaped over several lifetimes, dictated.

Never has a morsel of fish passed my lips-as i’m allergic to the ocean dwellers, but i’ve lived a simple life largely w/o strife, and strove to be outdoors more than in.

Sometimes your simple folksy prose sickens me.

I did not say everyone needed to eat fish. Count yourself lucky.

I’d advise you to lay off of my adjectives, verbs, nouns and especially the words I make up, as they can cause jibbering, jabbering and loss of acuity, in extreme cases.

Whatever you say Garrison Keillor…

A prairie blog companion?

Anyone has an idea why Italy would be such an outlier?

A good question that raises the only concern I have with this type of study – omitted variables etc. Spain and Italy compared to most of the countries in that graph, have had kids stay in the family home for much longer (into late 20s, 30s and now even 40s). Whilst undoubtedly there are bad things about staying with mum and dad (!), family bonds may – MAY – have some overall positive benefit.

Note that the further you go up the graph the more likely the country is a land of European immigrants.

Not saying it is the only cause but…

A worry I have concerns definitions of “poor mental health in east and west”. Oliver James (who has got a lot of airtime in the last decade in UK and possibly elsewhere but is admittedly quite controversial) investigated the diagnosis of “depression”. Although he found that the internationally used diagnosis code in many east Asian countries (principally those with large Han Chinese) was infrequently used, an alternative diagnosis was used, which westerners would interpret as “depression” but not exactly so in these local contexts. He (in the book I read) seemed to think Singapore was a “good model”. Hmmm, not in my experience of meeting lots of people on the ground, so to speak.

Now, more objective outcomes (suicides etc) may support the findings here, but comparisons of diagnosis codes etc across “east” and “west” are potentially hazardous. I myself in my numerous trips to Singapore when travelling between Aus and Europe met lots of guys who I thought were “severely anxious and/or depressed” but who were not diagnosed so by local physicians. This is NOT to say this article suffers from such problems – merely an alert that differential diagnoses should always be borne in mind. I certainly, from anecdotal evidence from a good friend who’s lived in Japan for 20+ years and is “as fully integrated as a westerner could be” would be quite suspicious about a lot of “official” Japanese data, given what he’s been told by natives and their reactions to mental health issues….but unfortunately I’m not at liberty to dish the dirt. TL;DR: This is probably correct but when drilling down, the story is a bit more complex than a simple graph like this portrays.

The graph is part of a much larger picture. Read The Spirit Level (the source for the graph) for a tsunami of evidence of dysfunction that accompanies large inequality, apart from mental illness.

And, even more worryingly, potentially our childrens’ and gradnchildrens’s lives, if findings in epigenetics are replicated (a subject discussed here a day or two ago among some of us in the comments to a link.) Whilst meta-analyses of good randomised trials are good (speaking as an “evidence based medicine” person) I think we should also keep caveats in mind with this type of research. Whilst I don’t disbelieve the conclusions here, we still live in an age of high-profile stories that may be wrong, or miss the point. For example, in today’s finding that vitamin D supplements in winter are actually of no value, that article totally misses other key roles of vitamin D by focusing on bone health only.

For example its been known for decades that the further you live from the equator, the higher your risk of developing MS. Vitamin D insufficiency was always the prime suspect, and IIRC the dominant theory at present is that intra-uterine exposure as a foetus is what may increase/decrease your risk. Observational/cohort studies in epidemiology of course notoriously change their recommendations almost daily as larger datasets, better correction of statistical confounding issues etc improve understanding. I’ve seen it in action when in Australia: the “Slip! Slop! Slap”” campaign to reduce skin cancer was quietly dropped when it was realised huger numbers of Aussies were suffering low vitamin D levels. Vitamin D is also implicated in mental health – first thing a new specialist did back in October last year was tested my level, finding me wayyyy below the reference range, and demanded supplements. So yeah I’m inclined to go with this article, but always keep a small degree of scepticism and think of potential other, underlying factors, when reading such a piece.

Exactly el_tel.

As I pointed out in another comment in this thread, the countries with higher rates of mental illness are countries of European immigration. This happened over an extremely short evolutionary timeline.

And as long as these vitamin studies do not equalize for genetic differences they will be useless. Plus it might not be vitamin D alone, but omega 3 in combination with D.

Yeah. As someone who has gone practically “all the steps in the treatment ladder” for anxiety/depression and who, although not a physician, knows from training how to read the literature, I admit I am very intrigued by things like omega 3, given their hypothesised role in the psychopharmacological literature in altering levels of the three main neurotransmitters. We are only now (via the GLAD study in England) beginning to try to understand how genes might be associated with the effectiveness of these “natural”/pharmaceutical medical interventions. We know the gene conferring lactose tolerance and the one conferring lesser physical effects in response to alcohol differ across Caucasian/East Asian groups – it’s only logical to wonder if there are other genetic differences too. (My personal view, FWIW, is that any differences are small and that the sociopolitical issues raised here ARE primary drivers….but I haven’t done research to back this up, hehe.)

Really sunny places Italy & Spain have excellent mental health, whereas in sunny Aussie, they’re a bit mental.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwekweCZZ0w

I will tell you that in my experience the dietary changes were everything. I totally resolved my mental illnesss without changing my sociopolitical situation. But I have Inuit blood in me. Not that for Inuit the SAD diet is more an issue for them than the general population.

Note that the mistake people make is to think that they can just add EPA and DHA into their overly Omega 6 saturated diet. It is the balance that is more important than the single fat. Many people will do better with more omega 6.

Excellent article.

I would recommend this article from Resilience that is in a similar vein. It reminds us about Durkheim and his measures of societal dysfunction:

“Radical Happiness: Moments of Collective Joy”

I do want to quibble with one point made by this author:

This sentence does capture the “cover story” that we’re given about mental illness and the medical industry’s approach to treating it, but I find it hard to believe that our medical and pharmaceutical Establishment really believe it. It’s so obvious that our social, economic, political and cultural environment is crushing many of us and perverting many others. The real purpose of our current medical approach to mental illness is to use drugs to keep people functioning “usefully” in this twisted society for as long as possible regardless of the harm these drugs might cause. The most extreme example of this approach is found in the military that is dispensing drugs to keep its trained killers in the field despite their human emotional reaction to the slaughter in which they’re participating.

One of the reasons that the Establishment went to war against hallucinogenic drugs in the 60s was that they do constitute a real treatment for many of the mental maladies suffered by us unfortunate residents of a sick society. They do so by unveiling for us the insanity of our current arrangements and the twisted nature of the values that have been shoved down our throats. As someone pointed out about the Army’s testing of LSD, the real problem was that they found that the test subjects who had been given LSD didn’t want to be soldiers any more. Can’t have that in a society devoted to perpetual war, can we?

“The real purpose of our current medical approach to mental illness is to use drugs to keep people functioning ‘usefully’ in this twisted society….” Nice insight. And couldn’t the same be said for alcohol and the additional “drugs” of gambling and entertainment? What would American society look like if we took away the booze and the casinos and the lotteries and the sports and the endless video screen diversions? I suspect that the ABSENCE on a particular day of suicides and mass shootings would be the lead story.

From reading this, I wonder if you can say that an effect of living in a dysfunctional society is low-level traumatic stress disorder – something like soldiers get under the stress of combat. Notice that I did not say post-traumatic stress disorder as the stress is still ongoing by living in that dysfunctional society. In earlier time there was the possibility of release by emigrating to a new colony but that option closed about a century ago. Now those who cannot cope long term all too often just decide to call it quits.

Not every soldier gets PTSD and not everyone in the “ghetto” ends up with mood disorders. There are just some of us who are genetically more sensitive to those stressors.

These are all 2018 papers:

https://www.nature.com/articles/mp201777

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/da.22712

https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/30025422

It’s time we stop fighting over whether it is nature OR nurture and accept that it is nature AND nurture that causes mental illness.

As long as the very first assumption for someone who does have significant distress caused pretty directly by the economic system is that DUH their problems are caused by economics, the unemployed person who gets more and more depressed as unemployment lasts longer and longer, yea their problems are not primarily being caused by biological problems. Now people who are really depressed and are doing pretty well by any measure may still be affected by the economic system but may have other causes in the mix.

But they know that genetics is the driver for resilience. Of course, you can eventually beat down anyone, but maybe you are not distinguishing mental illness and not having a good day. There are many “happy poor” people in the world so to me it is an more nature than nurture.

If we figure out why those of us ho are more sensitive to stress are effected more it will help everyone. Simply equalizing wealth would not have cured me.

But whatevs, unless you have been in my shoes, to hell and back with the treads wore down to the bone, it will be hard to see the distinction.

I’m depressed and poor. You can shove your sardines in a sack. Send me money.

How did that work out for Bourdain?

You might not need sardines, but to totally dismiss environmental factors under your control is short sighted. I am saying this from experience and because I care for you my brother/sister.

If we open this can of worms, we need to discuss how poverty and ghetto life affect mental health and stability. If we do that, then we need to accept that blacks and latinos are normal human beings who are driven to higher rates of drug use and crime by their environment. Can’t have that, can we? We need to stay focused on genetics.

Article in RT that addresses one avoidable cause for suicide by Robert Bridge, an American writer and journalist:

https://www.rt.com/op-ed/440431-veterans-suicide-us-war/

For all too many Americans, the “terrors of life” are great indeed, as some 20 veterans commit suicide every single day. This astonishing number accounts for 18 percent of the total suicide deaths in the country, yet veterans only represent 8.5 percent of the adult population.

Just this week, the non-profit organization Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America placed 5,520 American flags – one for each of the active-duty military personnel and veterans who have committed suicide so far this year – on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

I told my doctor that poverty is the most prevalent co-morbidity.

She’s better than some doctors, but I’m not sure this registered.

She thinks I should take pills for anxiety, while she takes trips to the Greek islands and Colorado for hers.

She assures me the side-effects are “rare” and “most” people are OK.

I wonder what are the side-effects of spending 2 weeks in Mykonos?

A shortage of Euros and a chronic Calvin Harris earworm?