Yves here. America has become a much-lower trust society since the stone ages of my youth, and this article describes one mechanism by which that imposes political and economic costs. It’s not hard to think of others. For instance, it was common for companies to do business on a close-to-handshake basis, where legal agreements were treated more as a way for both sides to make sure they had heard each other correctly than something they expected to have to rely upon. Even simple contracts are vastly longer than they were 30 years ago due to the parties feeling it necessary to spell out all sorts of scenarios in some detail. Similarly, it is mystifying, now that crime rates are much lower in the US than they were in the 1970s and 1980s, that kids are not allowed to walk home from school because their environment is supposedly unsafe.

Needless to say, it’s hard to imagine this happening in America:

You know there are other ways to respond to a threatening situation other than immediately blowing someone away.

The human way as shown by this cop. pic.twitter.com/1h83JsKbRb— Sven Henrich (@NorthmanTrader) October 3, 2018

By Nathan Nunn, Frederic E. Abbe Professor of Economics, Harvard University, Nancy Qian, Professor, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University and Jaya Wen, PhD student, Department of Economics, Yale University. Originally published at VoxEU

Cultural values and beliefs have an impact on social and economic development, but the interplay between culture and political institutions is still not well understood. This column examines the effect of trust on political stability in democratic and non-democratic regimes, specifically in the face of severe economic downturns. It finds that democratic regimes with high levels of trust are much less likely to experience leader turnover than low-trust countries, while there is no effect among non-democracies, and that countries with higher levels of trust experience faster economic growth in the years immediately following a recession.

A growing body of studies finds that cultural values and beliefs are important factors for social and economic development (Algan and Cahuc 2010, Collier 2017). However, our understanding of the interplay between culture and political institutions is still limited. While we have accumulated evidence about the effects that different institutional settings can have on the evolution of cultural traits (e.g. Tabellini 2010, Lowes et al. 2017, Becker et al. 2015), research on the effect of cultural traits on political or institutional outcomes is still in its infancy (Martinez-Bravo et al. 2017a, 2017b).

In a recent paper (Nunn et al. 2018), we seek to better understand how culture affects the political consequences of economic events. We examine the consequences of generalised trust, defined as the extent to which people believe that others can be trusted, for political stability in democratic and non-democratic regimes. Specifically, we posit that generalised trust affects how citizens evaluate their government’s performance in the face of severe economic downturns. In societies where trust is low, citizens may be less likely to trust the excuses of leaders and more likely to blame poor economic performance on poor decisions or low effort from politicians. In contrast, in societies where trust is high, citizens may be more likely to trust leaders when they argue that poor economic performance is outside of their control. This framework implies that, all else equal, economic recessions may be less likely to result in leader turnover in countries with higher levels of generalized trust, relative to countries with lower levels of trust.

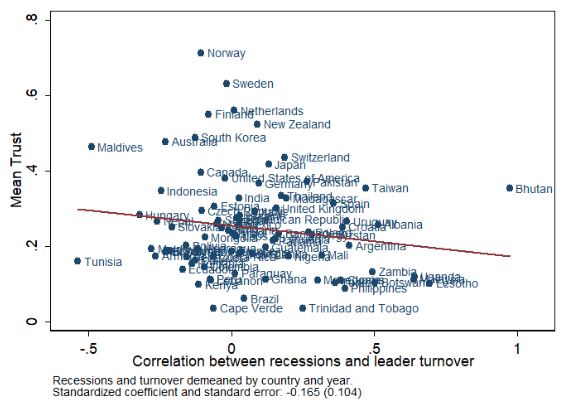

To illustrate the relationship between trust and political turnover during recessions for all countries for which data are available, we compute the correlation between recessions (defined as a period of negative average annual per capita GDP growth) and leader turnover for each country in the analysis, which is 0.070 (demeaning both variables by country and year). Figure 1 plots this country-level correlation against a country’s trust level. Since trust is a slow-moving cultural trait, we measure it as a time-invariant country-specific variable generated by averaging over all available surveys that ask the standard trust question.1

Figure 1 Bivariate correlation between countries’ level of generalized trust and the country-level correlation between the lagged occurrence of a recession and leader turnover

Although this correlation is informative, it is not conclusive. Omitted factors may exist that confound our interpretation of these relationships. Countries with different levels of trust may also differ in other ways that affect electoral turnover during recessions. For example, high trust countries may be richer on average, so policies that voters care about, such as public goods provision, may be less vulnerable to transitory economic downturns. At the same time, recessions may coincide with other events, such as military conflict, that can affect political turnover differentially across high- and low-trust countries. To address these difficulties, the analysis uses a difference-in-differences specification, with country and year fixed effects, and we control for a large number of possible omitted variables and conduct numerous placebo exercises to test the robustness of the main results.

We begin the analysis by focusing on democratic regimes, where citizens can more readily precipitate leader turnover through the mechanism of voting. The estimates show that when economic growth is negative, high-trust democracies are much less likely to experience leader turnover than low-trust countries. The magnitudes of the estimated effects are also sizeable. For example, according to the estimates, the presence of a recession is 12 percentage points more likely to cause political turnover in Italy than in Sweden. Similarly, it is 18.5 percentage points more likely to cause turnover in France than in Norway. The effects are large, especially given that mean turnover in the sample is 24.5%. The results are consistent with our hypothesis that in the face of a recession, individuals from low-trust countries are more likely to blame their politicians and remove them from office.

Since the electoral process plays an important role in this interpretation, we further examine the plausibility of our preferred mechanism by testing for the same effect among non-democracies. Consistent with our interpretation, we find no effect among non-democracies. We also find that the relationship only holds for regular leader turnovers, like those occurring due to elections, and not for irregular turnovers, like those occurring due to coups or assassinations.

As further confirmation of the importance of the electoral process for our main result, we test whether the effects that we find are most pronounced during election years. While we find effects in all years, the magnitude of the effect is much larger and more significant in election years. We also find that the effects are larger for parliamentary democracies than presidential ones, which may follow from the fact that parliamentary democracies have institutional procedures (i.e. a vote of no confidence) for removing the prime minister during the term. Moreover, we see the largest effects for democracies that have a fully free media and are more politically stable.2Together, these results suggest that trust influences political turnover in the face of economic downturns by affecting the outcomes of elections.

The final issue that we consider is the question of how trust and leader turnover in the face of recessions affects economic recovery following the recessions. Specifically, is greater trust and the resulting leader stability helpful in aiding economic recovery? Examining our sample of democratic regimes, we find that countries with higher levels of trust experience faster economic growth in the years immediately following a recession. In addition, countries that do not experience leader turnover following a recession also have faster economic growth during this time. These estimates, although not causal, are consistent with higher trust resulting in less leader turnover following a recession, which, in turn, results in better economic recovery.

Our findings starkly illustrate the important interplay between culture, politics, and economics. They show how deeply rooted cultural traits, like trust, affect political outcomes, which in turn are important for economic performance. Moreover, the findings are also important for policymakers, since they provide some clues for forecasting political instability during economic downturns.

See original post for references

Given the examples of Norway and Sweden, I wonder how much the relative strength (or existence, even) of the social safety net contributes to creating trust. Certainly the loss of social safety backstops in the US coincided with a massive decline in trust here.

That, and the whole warped rule of law, rich-jerks-get-off-scott-free business.

If you think about it, taxation is a form of trust.

Yes, strictly from an MMT standpoint, it does not fund the government, but it does have a huge control on how governments allocate their resources and to whom.

A high trust society is a prerequisite for a strong safety net. Otherwise we will see conservative politicians exploiting differences in the population to weaken the safety net.

Conservative politicians are ruthlessly using this in the US against African American populations to undermine support for a stronger social safety net.

As usual, Altandmain, you make excellent points. Thank you!

Could be, but I have a sneaking suspicion that Scandinavian societies were already relatively high trust societies before they built their modern social welfare systems, though maybe there’s been a virtuous circle at work in this matter.

In 10 days of playing mom & dad for our 10 & 12 year old nephews, I paid close attention, looking for an unescorted child walking to elementary school, and never saw one, although there were many dozens that walked there with mom in tow.

Yes, it’s all out of whack, the crime rate has fallen precipitously, and yet we’re terrified and it spills over to the kids, who attend ad hoc concentration camps in the guise of our schools, which are almost all fenced in around the perimeter.

Contrast that with the free range attitude my parents had in the midst of the worst crime era in the 70’s…

Come home from school @ 3 pm, and then disappear for the next 3 hours until dinner, with absolutely no way for them to keep track of what we were up to, or to even contact us.

Thanks for this post.

You write in the intro: For instance, it was common for companies to do business on a close-to-handshake basis, where legal agreements were treated more as a way for both sides to make sure they had heard each other correctly than something they expected to have to rely upon. Even simple contracts are vastly longer than they were 30 years ago due to the parties feeling it necessary to spell out all sorts of scenarios in some detail.

True. That was before the neoliberal/profit maximization paradigm had taken over businessess. (30 years ago the older upper-level managers raised/schooled in the pre-neoliberal world were still in charge.) With neoliberalism and “economic man” working to maximize his satisfaction/advantage always as the new ruling paradigm, who can trust anyone else based mostly on a handshake? Distrust is a natural biproduct of neoliberalism, imo. Distrust is also ‘sand in the gears’ of business.

This essay provides an example of our disturbing tendency to resort to the measurement and analysis of social science to confirm a matter of common sense; in this case, that in societies where people trust each other, there is less political volatility and quicker economic recovery. I use the word “disturbing” because such unnecessary and cumbersome reliance on social science indicates that we no longer trust our own intuition and life experience. And when we no longer trust ourselves, how are we to learn to trust others? Yet this article was worthwhile for the video alone, which showed the effectiveness (and humanity) of our former law enforcement strategy of initially attempting to deescalate a difficult situation, an approach we jettisoned in favor of the use of overwhelming force from the very inception of an incident. Could there be stronger evidence of a sick society, on the gut or intuitive level, than the constant stream of videos in which cops shoot citizens for the flimsiest of reasons or for no reason at all?

https://newtonfinn.com/2011/12/15/would-paladin-have-shot-bin-laden/

According to research done by Mayer Hillman, the reason parents don’t allow children to walk to school is because of the risk of traffic fatalities. This is based on research done in the 70s – 90s and surveys of parents. To provide one anecdote, my supposedly wealthy suburb has virtually no sidewalks except along major thoroughfares. If parents allowed kids to walk home from school the kids would literally share the road with traffic.

Hillman’s book is available for free on his website.

So instead of making the whole community more livable by BUILDING SOME FRICKIN’ SIDEWALKS, the ‘solution’ is to have parents helicopter kids everywhere, which not only massively streeses the parents out but has the added perverse outcome of negating much of the ‘added safety’ simply by drastically increasing the vehicle traffic around schools. I’ve seen enough ‘child killed by being run over in busy school dropoff area’ installments on the local news that I seriously question the ‘kids are safer’ claim. Specifically, note the lawyerly parsing in “Road accidents involving children have declined…” – sure, but to what extent have said accidents moved from the roads to the now-insanely-busy-with-traffic school dropoff areas, entry- and exitways?

Where I grew up, more or less 100% of kids walked/biked or took the schoolbus to school, and from elementary through high school I don’t recall hearing about a single one of my many hundreds of schoolmates being involved in anything beyond a scrapes-and-bruises bike crash.

There are other issues. On the local level, MMT does not apply, so raising property taxes will be an act of trust. Plus suburban types utterly loathe property taxes.

Then there is the fear of strangers, another low trust indicator in the US.

My understanding (through casual reading) is that as suburban areas have become more dispersed, sidewalks are deemed useless. The dispersion has occurred because people who could afford it have bought into that way of life (large isolated houses on relatively large lots). The traffic jams in front of schools are truly grotesque, but people evidently accept them.

The dispersion also makes it more difficult to construct routes for school busses, just as it does for every other form of public transportation.

Maybe the drive toward dispersion reflects loss of trust in neighbors?

This stops at a rather arbitrary point, since it seems to treat trust as a catchall uncaused variable. Do trust levels rise and fall on their own, for no discernible reason? At the most superficial level, this would seem to say only that people give more credence to the explanations of those they find credible, but this snake will eat it’s own tail pretty rapidly.

Also doesn’t deal with another variable. How credible are those seeking to replace the leadership?

And are all recessions equal, or are there aspects of the 1870, 1929, and 2007 ones that stand out from the others?

I’m reminded of the Baffler’s “this is not a blip” piece from the other day, because this piece falls into a subgenre it deals with at some length.

Narratives in which our ascent up the spiral staircase of gradual progress was inexplicably interrupted about 2007 or 2016, depending on your subset, due to a rising toxicity that apparently had no connection to policies previously pursued. Much talk of “rebuilding trust” without actually doing anything to create a functioning basis for trusting. Basically just doubling down on the secular liberal version of justifying the ways of God to man.

Maybe they could just give us all copies of “Who Moved My Cheese? “

Devil’s Advocate here Yves. What if the crime rates have gone down because kids are not allowed to walk home from school? All those little potential victims and criminals are off the streets.

There is evidence that crime rates have fallen because we removed lead from gasoline. Of course, I imagine that if Trump becomes aware of this, he will do his best to make leaded gas widely available once again.

The end of the demographic bulge (‘Baby Boom’) and the legalization of abortion have also been suggested. And, in a sense, crime in the sense of attacks on other people has been nationalized; a desire for extra aggro can be satisfied by just watching the news.