Yves here. In case you hadn’t noticed it, the economics discipline has doctrinal norms. Academics who stray too far from it find themselves welcome only at the small number of colleges and universities, such as the University of Missouri – Kansas City and the University of Massachusetts – Amherst, that embrace heterodox views.

The top five economics journals play a large role in enforcing the orthodoxy. Jamie Galbraith has described how he’d submit suitably mathed-up papers to one of the heavyweights, get an initial positive response, but when they understood where he was going, they’d alway reject the paper. The reviewers would claim that the mathematics were flawed, when that was not the case. But being published by the top five is essential to advancing in prestigious economics faculties, such as Harvard, Chicago, Princeton, and MIT.

It should be noted that no real science has a rigid hierarchy of journals like this. The article documents disfunction among the editors at these journals, such as incest and clientelism.

By James Heckman, Henry Schultz Distinguished Service Professor of Economics, University of Chicago; Founding Director, Center for the Economics of Human Development and Sidharth Moktan, Predoctoral Fellow, Center for the Economics of Human Development, University of Chicago. Originally published at VoxEU

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the ‘Top Five’ economics journals have a strong influence on tenure and promotion decisions, but actual evidence on their influence is sparse. This column uses data on employment and publication histories for tenure-track faculty hired by the top US economics departments between 1996 and 2010 to show that the impact of the Top Five on tenure decisions dwarfs that of non-Top Five journals. A survey of US economics department faculties confirms the Top Five’s outsized influence.

Anyone who talks with young economists entering academia about their career prospects and those of their peers cannot fail to note the importance they place on publication in the so-called Top Five journals in economics: the American Economic Review, Econometrica,the Journal of Political Economy,the Quarterly Journal of Economics, and the Review of Economic Studies.The discipline’s preoccupation with the Top Five is reflected in the large number of scholarly papers that study aspects of the these journals, many of which acknowledge the Top Five’s de facto role as arbiter in tenure and promotion decisions (e.g. Ellison 2002, Frey 2009, Card and DellaVigna 2013, Anauti et al. 2015, Hamermesh 2013, 2018, Colussi 2018).

While anecdotal evidence suggests that the Top Five has a strong influence on tenure and promotion decisions, actual evidence on such influence is sparse. Our paper (Heckman and Moktan 2018) fills this gap in the literature. We find that the Top Five has a large impact on tenure decisions within the top 35 US departments of economics, dwarfing the impact of publications in non-Top Five journals. A survey of current tenure-track faculty hired by the top 50 US economics departments confirms the Top Five’s outsize influence.

Our empirical and survey-based findings of the Top Five’s influence beg the question: is the Top Five an adequate filter of quality? Extending the analysis of Hamermesh (2018), we show that appearance of an article in the Top Five is a poor predictor of quality as measured by citations. Substantial variation in the citations accrued by papers published in the Top Five and overlap in article quality across journals outside the Top Five make aggregate measures of journal quality such as the Top Five label and Impact Factors poor measures of individual article quality. This is a view expressed by many economists and non-economists alike.1

There are many consequences of the discipline’s reliance on the Top Five. It subverts the essential process of assessing and rewarding original research. Using the Top Five to screen the next generation of economists incentivises professional incest and creates clientele effects whereby career-oriented authors appeal to the tastes of editors and biases of journals. It diverts their attention away from basic research toward strategising about formats, lines of research, and favoured topics of journal editors, many with long tenures. It raises the entry costs for new ideas and persons outside the orbits of the journals and their editors. An over-emphasis on Top Five publications perversely incentivises scholars to pursue follow-up and replication work at the expense of creative pioneering research, since follow-up work is easier to judge, is more likely to result in clean publishable results, and is hence more likely to be published.2 This behaviour is consistent with basic common sense: you get what you incentivise.

In light of the many adverse and potentially severe consequences associated with current practices, we believe that it is unwise for the discipline to continue using publication in the Top Five as a measure of research achievement and as a predictor of future scholarly potential. The call to abandon the use of measures of journal influence in career advancement decisions has already gained momentum in the sciences. As of the time of the writing of this column, 667 organisations and 13,019 individuals have signed the San Francisco Declaration of Research Assessment, a declaration denouncing the use of journal metrics in hiring, career advancement, and funding decisions within the sciences.3 Economists should take heed of these actions. We provide suggestions for change in the concluding portion of this column.

Documenting the Power of the Top Five

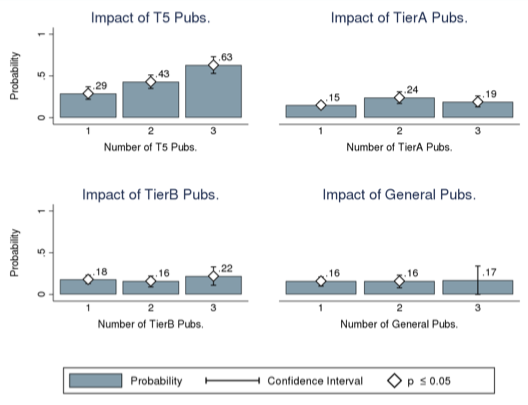

We find strong evidence of the influence of the Top Five. Without doubt, publication in the Top Five is a powerful determinant of tenure and promotion in academic economics. We analyse longitudinal data on employment and publication histories for tenure-track faculty hired by the top 35 US economics department between 1996 and 2010. We find that Top Five publications greatly increase the probability of receiving tenure during the first spell of tenure-track employment (see Figure 1). This is true if we limit samples to the first seven years of employment. Estimates from duration analyses of time to tenure show that publishingthree Top Five articles is associated with a 370% increase in the rate of receiving tenure, compared to candidates with similar levels of publication in non-Top Five journals. The estimated effects of publication in non-Top Five journals pale in comparison.

Figure 1 Predicted probabilities for receipt of tenure in the first spell of tenure-track employment

Notes: The figures plot the predicted probabilities associated with different levels of publications by authors in different journal categories, where the predictions are obtained from a logit model. White diamonds on the bars indicate that the prediction is significantly different than zero at the 5% level.

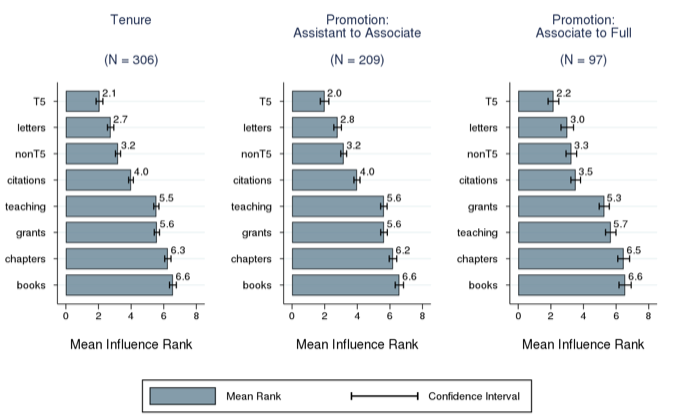

A survey of current assistant and associate professors hired by the top 50 US economics departments corroborates these findings. On average, junior faculty rank Top Five publications as being the single most influential determinant of tenure and promotion outcomes (see Figure 2).4

Figure 2 Ranking of performance areas based on their perceived influence on tenure and promotion decisions

Notes: The figure summarises respondents’ rankings of either performance areas. Responses are summarised by type of career advancement: tenure receipt, promotion to assistant professor, and promotion to associate professor. The bars present mean responses for each performance area. Respondents were given the option to not rank any or all of the eight performance areas. As a result, the number of respondents varies across the performance areas.

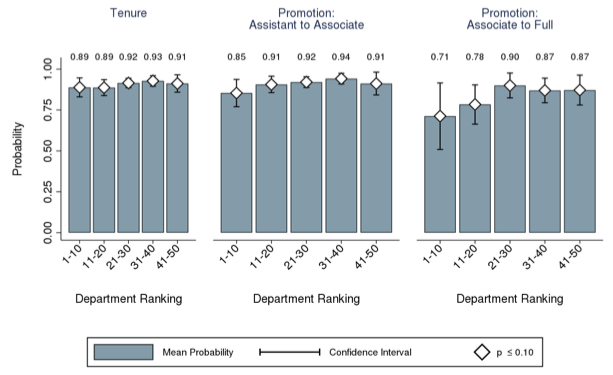

Responses to our survey reveal a widespread belief among junior faculty that the effect of the Top Five on career advancement operates independently of differences in article quality. To separate quality effects from a Top Five placement effect, we ask respondents to report the probability that their department awards tenure or promotion to an individual with Top Five publications compared to an individual identical to the first individual in every way except that he/she has published the same number and quality of articles in non-Top Five journals. If the Top Five influence operates solely through differences in article impact and quality, the expected reported probability would be 0.5. The results in Figure 3 show large and statistically significant deviations from 0.5 in favour of Top Five publication. On average, respondents from top 10 departments believe that the Top Five candidate would receive tenure with a probability of 0.89. The mean probability increases slightly for lower-ranked departments.

Figure 3 Probability that a candidate with Top Five publications receives tenure or promotion instead of an identical candidate with non-Top Five publications, ceteris paribus

Notes: The figure summarises respondents’ perceptions about the probability that a candidate with Top Five publications is granted tenure or promotion by the respondent’s department instead of a candidate with non-Top Five publications, ceteris paribus. Responses are summarised by type of career advancement: tenure receipt, promotion to assistant professor, and promotion to associate professor. The bars present mean responses for each performance area. White diamonds indicate that the mean response is significantly different than 50% at the 10% level.

The Top Five as a Filter of Quality

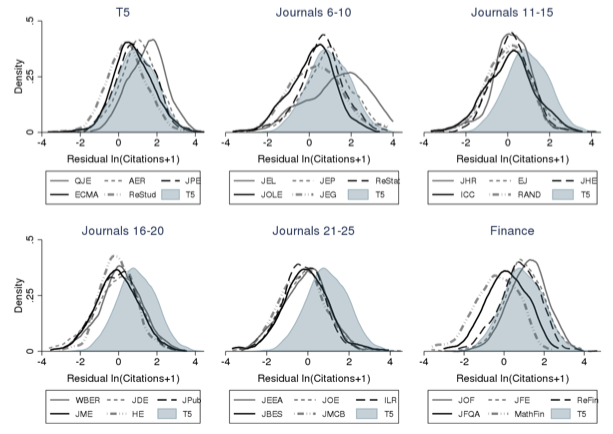

The current practice of relying on the Top Five has weak empirical support if judged by its ability to produce impactful papers as measured by citation counts. Extending the citation analysis of Hamermesh (2018), we find considerable heterogeneity in citations within journals and overlap in citations across Top Five and non-Top Five journals (see Figure 4). Moreover, the overlap increases considerably when one compares non-Top Five journals to the less-cited Top Five journals. For instance, while the median Review of Economics and Statisticsarticle ranks in the 38thpercentile of the overall Top Five citation distribution, the same article outranks the median-cited article in the combined Journal of Political Economyand Review of Economic Studies distributions.

Figure 4 Distribution of residualalog citations for articles published between 2000 and 2010 (as at July 2018)

Source: Scopus.com (accessed July 2018)

Note: a The table plots distributions of residual log citations obtained from a model that estimates log(citations+1) as a function of third-degree polynomial for years elapsed between the date of publication and 2018, the year citations were measured. This residualisation adjusts log citations for exposure effects, thereby allowing for comparison of citations received by papers from different publication cohorts.

Definition of journal abbreviations: QJE–Quarterly Journal Of Economics, JPE–Journal Of Political Economy, ECMA–Econometrica, AER–American Economic Review, ReStud–Review Of Economic Studies, JEL–Journal Of Economic Literature, JEP–Journal Of Economic Perspectives, ReStat–Review Of Economics And Statistics, JEG–Journal Of Economic Growth, JOLE–Journal Of Labor Economics, JHR–Journal Of Human Resources, EJ–Economic Journal, JHE–Journal Of Health Economics, ICC–Industrial And Corporate Change, WBER–World Bank Economic Review, RAND–Rand Journal Of Economics, JDE–Journal Of Development Economics, JPub–Journal Of Public Economics, JOE–Journal Of Econometrics, HE–Health Economics, ILR–Industrial And Labor Relations Review, JEEA–Journal Of The European Economic Association, JME–Journal Of Monetary Economics, JRU–Journal Of Risk And Uncertainty, JInE–Journal Of Industrial Economics, JOF–Journal Of Finance, JFE–Journal Of Financial Economics, ReFin–Review Of Financial Studies, JFQA–Journal Of Financial And Quantitative Analysis, and MathFin–Mathematical Finance.

Restricting the citation analysis to the top of the citation distribution produces the same conclusion. Among the top 1% most-cited articles in our citations database,5 13.6% were published by three non-Top Five journals.6

Low Editorial Turnover and Incest

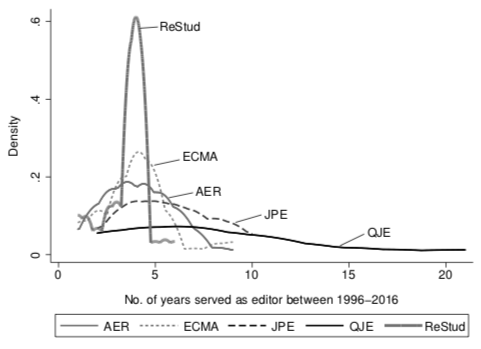

Figure 5 Density plot of the number of years served by editors between 1996 and 2016

Source: Brogaard et al. (2014) for data up to 2011. Data for subsequent years collected from journal front pages.

Compounding the privately rational incentive to curry favour with editors is the phenomenon of longevity of editorial terms, especially at house journals (see Figure 5). Low turnover in editorial boards creates the possibility of clientele effects surrounding both journals and their editors. We corroborate the literature that documents the inbred nature of economics publishing (Laband and Piette 1994, Brogaard et al. 2014, Colussi 2018) by estimating incest coefficients that quantify the degree of inbreeding in Top Five publications. We show that network effects are empirically important – editors are likely to select the papers of those they know.7

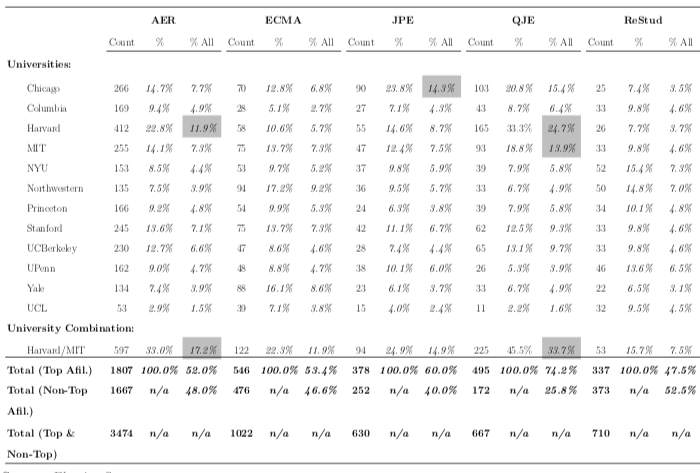

Table 1 Incest coefficients: Publications in Top Five between 2000 and 2016, by author affiliation listed during publication

Source: Elsevier, Scopus.com.

Notes: The table reports three columns for each Top Five journal. The left most columns report the number of articles that were affiliated to each university. The middle columns present the percentage of articles published in the journal that were affiliated to the university out of all articles affiliated to the list top universities. The right most columns present the percentage of articles published in the journal that were affiliated to the university out of all articles published in the journal. An author is defined as being affiliated with a university during a given year if he/she listed the university as an affiliation in any publication that was made during that specific year. An article is defined as being affiliated with a university during a specific year if at least one author was affiliated to the university during the year.

Discussion

Reliance on the Top Five as a screening device raises serious concerns. Our findings should spark a serious conversation in the economics profession about developing implementable alternatives for judging the quality of research. Such solutions necessarily de-emphasise the role of the Top Five in tenure and promotion decisions, and redistribute the signalling function more broadly across a range of high-quality journals.

However, a proper solution to the tyranny will likely involve more than a simple redefinition of the Top Five to include a handful of additional influential journals. A better solution will need to address the flaw that is inherent in the practice of judging a scholar’s potential for innovative work based on a track record of publications in a handful of select journals. The appropriate solution requires a significant shift from the current publications-based system of deciding tenure to a system that emphasises departmental peer review of a candidate’s work. Such a system would give serious consideration to unpublished working papers and to the quality and integrity of a scholar’s work. By closely reading published and unpublished papers rather than counting placements of publications, departments would signal that they both acknowledge and adequately account for the greater risk associated with scholars working at the frontiers of the discipline.

A more radical proposal would be to shift publication away from the current journal system with its long delays in refereeing and publication and possibility for incest and favouritism, towards an open source arXiv or PLOS ONE format.8 Such formats facilitate the dissemination rate of new ideas and provide online real-time peer review for them. Discussion sessions would vet criticisms and provide both authors and their readers with different perspectives within much faster time frames. Shorter, more focused papers would stimulate dialogue and break editorial and journal monopolies. Ellison (2011 )notes that online publication is already being practiced by prominent scholars. Why not broaden the practice across the profession and encourage spirited dialogue and rapid dissemination of new ideas? This evolution has begun with a recently launched economics version of arXiv.

Under any event, the profession should reduce incentives for crass careerism and promote creative activity. Short tenure clocks and reliance on the Top Five to certify quality do just the opposite. In the long run, the profession will benefit from application of more creativity-sensitive screening of its next generation.

See original post for references

From Yves preface:

“It should be noted that no real science has a rigid hierarchy of journals like this.”

‘nough said.

From this year’s not-quite-the-Nobel Prize winner Paul Romer:

And scientists more generally. You heard the man.

Also too, economics departments across he land are reclassifying themselves as STEM,

in order to engage in a little regulatory arbitrage vis-a-vis visas.

Resistance is futile.

Disagree that resistance is futile.

If they feel a need to reclassify as STEM, that’s not a good symptom — unless, of course, you’re all about stochastic equilibrium mumboJumbo. However, try that around an engineering program and prepare to be ridiculed out of the college.

You also cannot ignore the fact that many/most of the folks who perform editorial and review tasks at these journals have paid gigs with the Federal Reserve, or receive some other form of remuneration through research grants and the like, which means that the they are less likely to take a jaundiced view of the institution’s actions.

If you entered college post-1970s and were not to the manor born, all of academia seems like a horrible feudal system with serfs (adjuncts and most grad students, plus future debt peon students) and nobles (tenured olds and their children plus the wealthy). I would have loved to have a career in academia and I actually enjoy both teaching and research. But I have no connections and am a horrible schmoozer so I gave up after watching my favorite graduate teaching assistants suffer and associate professors not get tenure.

The real solution is not reform but burn the whole thing to ground and replace it with an open source system and micro contributions, like what is happening with journalism, another sacred cow that deserves to die.

By the way, thank you for once again exposing what a crock mainstream economics is.

There is an old story I was told by an econometrician that the journal Econometrica was the only western economics or political journal that was not banned in Ceaucescu era Romania because according to the censor: ‘it made no sense and is clearly of no use to anybody.

Here’s the result from searching for “Money and Banking.”

How is the mining industry involved in the supply of money? Gold digging?

Academic economics is incredibly corrupt as a field. If you want to see what economists think without a filter, go to the forum econjobrumors.com and you will see a depravity and lack of ethics on display for most economists. Related to this is that academic economics as an institution is setup to ensure homogeneity in thought that coincides with what elites what. Did you know that economists are among the highest paid professors at most universities? The starting salary is around 200k/year in many public universities, and can go as high as a million per year in private universities for senior professors. But the catch is that the only way you can publish in these top 5 journals and the only way to get hired or tenure is to reinforce a prevailing ideology in support of elites.

Great post. Thank you!

Very glad that I previously read Tomasky today at NYT — arguing that (in the US, Dems) need to drive a stake into the heart of the supply side narrative and come up with a new story. It’s an easy reach to extend his argument to Labor in UK (where Corbyn is talking a new story), as well as other PIIGs and other nations. IOW, it’s these politicians up against schlerotic economics journals: in an era of global warming, inequality, and refugees, I’ll gamble on the new narrative.

No matter how hard those econ journals try, no matter how elaborate the math, IMVHO we are entering an era when overspecialization in econ won’t be able to stand up to the kind of interdisciplinary, fertile work coming out of places like evonomics.com, INET (Institute for New Economic Thinking), and NC.

What is the code of conduct for the economics ‘profession’? Which body enforces it? What are the sanctions for failing to abide by the rules and standards of this ‘profession’?

Economics isn’t a science, nor should it be called a profession.

Economics as currently practiced is not a science — it is a religion.

Once you recognize this, the behaviour of its adherents begins to make some sense.

With all due respect, “It should be noted that no real science has a rigid hierarchy of journals like this” is not true. All scientific disciplines operate rankings of journals and maybe economics seems bad, but it is not unique in the least. It’s not even the worst.

Large organizations and corporations control the largest and most “prestigious” journals while defining what qualifies as prestigious, and faculty around the world are judged on whether they publish in those same (English-language) top-ranked journals. This article itself cites Scopus, owned by Elsevier, the evil demon king of scientific publishing. Most health and bio sciences have their most prestigious journals published by the same. Some publishers, such as the American Chemical Society, both own and publish the top-ranked journals AND require that universities pay for subscriptions to those same journals to receive accreditation for their chemistry programs (i.e. for students to graduate and be officially recognized in the profession). It’s the same for American Psychology Association. They also charge individual researchers huge membership fees to, again, put on their C.V. for promotion and tenure.

Don’t worry, all disciplines are corrupt and awful on this front. :) I won’t even get started on open access fees and all the other issues in scholarly publishing. It’s a huge racket.

I need to find a book on how the study of Political Economy morphed into the study of Economics.

How an academic journal called the Journal of Political Economy can, with a straight face, act as one of the exclusive shoe-shine-boys of the capitalist class has to be one of the singularly monumental feats of head-standing co-optation in the history of academia.

What is really needed is a Journal of Empirical Economics to counterbalance what those other five journals publish. To get published in this one, your paper would have to correspond with real world economics and would be provable by what actually happens there. Just to give a dig at the other publications, they could have as their motto “Our brand of Economics doesn’t use a narrow-band filter!”

See

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/12/whats-wrong-heterodox-economics-journals.html

What’s Wrong with Heterodox Economics Journals?

Posted on December 17, 2014 by L. Randall Wray | 7 Comments

By L. Randall Wray