Lambert here: Makes our own Civil War look like a blip. However, at least some of the conclusions seem to be borne out for our Civil War, too: Increase in state capacity, for example.

By Lixin Colin Xu, Lead Economist, Development Research Group, World Bank, and Li Yang, Postdoc, Paris School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

The Taiping Rebellion, from 1851 to 1864, was the deadliest civil war in history. This column provides evidence that this cataclysmic event significantly shaped China’s Malthusian transition and long-term development that followed, especially in areas where the experiences that stemmed from the rebellion led to better property rights, stronger local fiscal capacity, and rule by leaders with longer-term governance horizons.

How do civil wars shape a country’s development? And what are the underlying mechanisms? The past decades have witnessed a surge of this literature (e.g. Blattman and Miguel 2010), most of which deals withthe economic legacies of war and conflicts. Still, the long-term impacts of war, as well as the key mechanisms that underlie these impacts, remain poorly understood. As Blattman and Miguel (2010, p. 42) point out, “[u]nfortunately, we have little systematic quantitative data with which to rigorously judge claims about the evolution of institutions during and after civil wars… the social and institutional legacies of conflict are arguably the most important but least understood of all war impacts”. In a recent paper (Xu and Yang 2018), we add to this literature of civil wars by examining the long-term consequences of the Taiping Rebellion.

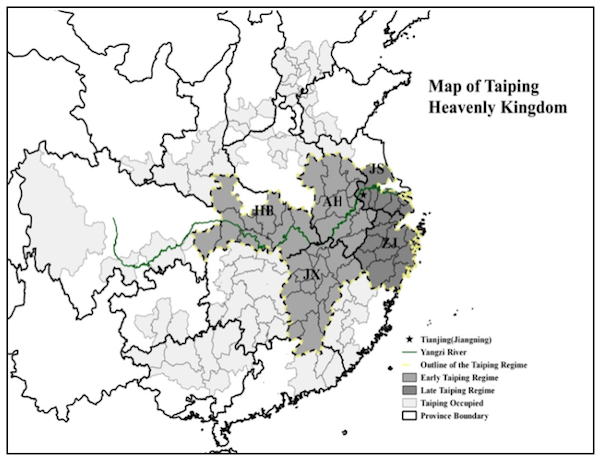

The Taiping Rebellion, from 1851 to 1864, was a millenarian movement led by Hong Xiuquan, a school teacher who failed the Qing Scholar examinations and then became a Christian. He established the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom with its capital at Nanjing. During its reign, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom controlled much of southern China, including Jiangsu, Anhui, Hubei, Jiangxi, and Zhejiang provinces. Its control over these areas were not complete – some were jointly controlled by both Qing and the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, or their control changed hands frequently.

Figure 1 Map of Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

Notes: HB:Hubei Province; JX: Jiangxi Province; AH: Anhui Province; JS: Jiangsu Province; ZJ: Zhejiang Province. The legends are Tianjin (Jiangning); Yangzi River; Ourline of the Taiping Regime; Early Taiping Regime; Later Taiping Reime; Taiping Occupied: Province Boundary.

Unfolding in the mid-19th century amid what Galor (2005) calls the Malthusian regime, the Taiping Rebellion was the deadliest civil war in human history, and a critical juncture for China’s turn to modernity (Ho 1959, Fairbank 1992, Pinker 2011). Recent estimates from Cao (2001) suggest that the casualties amounted to 70 million. Indeed, the devastation left behind after the Taiping Rebellion gave those densely populated regions a new lease of life during the years of restoration that followed. However, the attention of historians has been drawn again and again to the revolt largely because the Taiping Rebellion was a watershed moment in Chinese history. The modern history of China has been drastically changed by those tumultuous years – to fight the rebellion, the Qing government was forced to decentralise, putting regional armies and public finance under the control of local leaders and fundamentally altering China’s evolution (Fairbank 1992). Strong provincial leaders emerged – warlords began to segment China, and to experiment with various forms of governance in these regions.

Against this backdrop, we investigate the rebellion’s long-term impacts and the underlying mechanisms responsible for them. To proceed, we draw from the institutional background and the literature to derive hypotheses. We focus on several aspects of the rebellion and Qing’s responses.

- First, the land policies in the early and late stages of the rebellion differed markedly. The protection of land property rights was better in the late stages than in the early ones. We hypothesise faster post-war population recovery and better long-term development for the late Taiping areas than the early Taiping areas.

- Second, since the areas near the rebellion’s capital city, Nanjing, were more likely to be viewed as stationary bases for the rebellion, we hypothesise that their governance and policies were likely better than those of other Taiping areas, as Olson’s theory of stationary banditry implies (Olson 1993).

- Third, the rebellion occurred in years of solid technological progress. We examine whether the unprecedented amount of losses of life associated with the rebellion ultimately led to the subsequent Malthusian transition, characterised by income growth along with lower population growth (Galor and Weil 2000, Voigtlander and Voth 2013b).

- Fourth, we note that the Qing government instituted fiscal decentralisation to finance local militias against the rebel army – thus, we examine whether this fiscal decentralisation acted as taxation that hindered trade, or state capacity that facilitated development (Besley and Persson 2009).

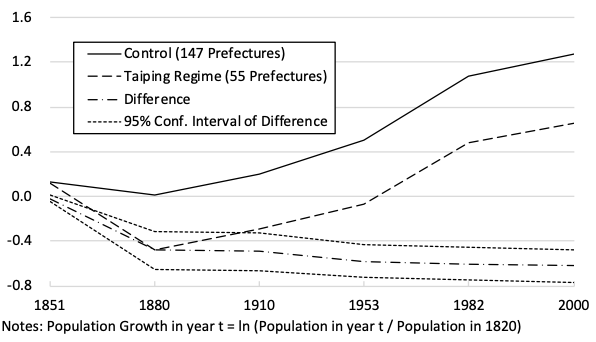

We analyse a dataset of prefectures in China Proper that were and were not affected by the rebellion from 1820 to the present day. We focus on population levels and cross-sectional development outcomes between 2000 to 2010. Population growth is a common measure of long-term development (e.g. Acemoglu et al.2002, Jia 2014), and it serves as an indicator of the Malthusian transition. We also examine other complementary aspects such as income levels, fiscal capacity, industrialisation, and human capital, which shed light on the mechanisms of the Malthusian transition. When looking at the population impact, we use a difference-in-difference (DID) approach, and we estimate the differences of the population growth rates (from the base period) between the control group (i.e. the prefectures that were unaffected by the rebellion) and the treatment group (i.e. the prefectures in which the rebellion took place). To address potential omitted-variables biases and measurement errors when examining the impact of the rebellion, we also apply the instrumental variable (IV) approach.

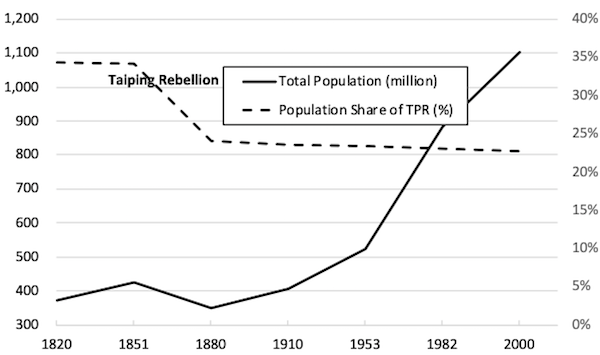

We find that the rebellion permanently shifted the rebellion areas’ development trajectories.In areas that experienced the rebellion, the post-warpopulation increases (compared to the baseline year 1820) remain 38% to 67% lower than in areas that were unaffected by the war, even after the passage of one-and-a-half centuries(see Figure 2). The long-term impact on the population by the rebellion is illustrated in Figure 3, which depicts the evolution over time of the total population and the share of the rebellion areas in the total population of the sample prefectures. The rebellion prefectures’ population share has dropped from 34.2% in 1820 to 22.7% in 2000.

Figure 2 Population growth over time for Taiping Regime areas

Figure 3 Population growth and population share of Taiping versus all sample Chinese prefectures

Moreover, the rebellion’s long-term effects on development are similar to those that emerged in Europe following its devastating experience of the Black Death (Voigtlander and Voth 2013). When augmented with favourable changes in institutions and fiscal capacity, the Rebellion facilitated China’s ensuing Malthusian transition – that is, from the Malthusian regime of high population growth and no real-income growth to the modern growth regime of sustained income growth with limited population growth (Galor and Weil 2000). This conclusion is supported by several pieces of evidence.

- First, the rebellion areas went on to have greater long-run fiscal capacity and faster growth of modern sectors.

Based on the OLS and 2SLS estimates, in 2010, one-and-a-half centuries after the Taiping Rebellion, fiscal revenue per capita in the Taiping areas are at least 50% (0.6 standard deviations) higher than in other areas – a huge effect. This supports the war-induced state-capacity hypothesis. Furthermore, based on the OLS, Taiping areas have a significantly higher share of modern sectors – these areas’ share of manufacturing in GDP is higher by 4.6% (0.4 standard deviations). Based on the 2SLS, the Taiping areas’ average schooling level is 13% higher – again a large effect. These results support the Malthusian transition hypothesis.

- Second, Taiping-governed areas with both big population losses and good protection of land property rights (i.e. the Late Taiping areas) experienced faster post-war population recovery – they also witness better long-term fiscal capacity, more extensive modern-sector development, and higher income levels.

Compared to the control group, the Early Taiping areas experienced an immediate drop in population growth (compared to population in 1820) of 36% (or 45 log points) after the war, and a further drop of 11 log points until the Communist takeover in the mid-20thcentury. This is consistent with the finding that poor land property rights in the Early Taiping areas led to more wasteland and slower population recovery. In contrast, the Late Taiping areas experienced faster population recovery than the Early Taiping areas, with a large drop in population growth by 40% (or 50 log points) in 1880, and relative population growth was greater than the control group by 19 log points between 1880 and 1953. This partial recovery in population could be explained by two forces. First, convergence toward the mean occurred when factors such as labour flowed to the region with a higher land/labour ratio, and second, good land property rights in the Late Taiping areas led to faster re-utilisation of wasteland, which facilitated population growth.

Furthermore, the Early and the Late Taiping areas have vastly different long-term development. Compared to the control groups, the Early Taiping areas are now similar except that they have lower GDP per capita by 22 log points. In sharp contrast, the Late Taiping areas have advanced much further in the Malthusian transition than the control group – GDP per capita is 60% higher, fiscal capacity is 160 higher, the manufacturing share in GDP is 17% (1.2 standard deviation) higher. These results support the Malthusian hypothesis. The strong positive effects in the context of good property rights (i.e., Late Taiping areas), and the negative effects in the roving-bandit Early Taiping areas support the idea that the large population losses associated with large wars exert positive long-term impact only when institutions are better.

- Third, the effects of big population losses in areas close to the rebellion’s capital city are similar to those of the rebel areas that featured good land property rights.

There is one interesting exception to those observed in the rebel areas with good land property rights. Areas near the rebel capital exhibit higher levels of schooling than elsewhere. We hypothesise that in areas close to Nanjing, capitalist elites likely had more power than landed elites, and that their influence, coupled with rising fiscal capacity, led to increased schooling. Our reasoning is that human capital and physical capital are complements, and that the capitalist elites would have pushed for the provision of public schooling for the their own benefit (Galor et al. 2009). Indeed, we find that areas near Nanjing currently have significantly higher schooling levels than elsewhere.

- Fourth, fiscal decentralisation and the strengthening of fiscal capacity led to a faster Malthusian transition, including lower population levels, and stronger long-term development.

We measure the strengthening of fiscal capacity using the intensity of Likin, an internal tariff introduced by the Qing Empire during the Rebellion for war financing, which was abolished in 1930s. Increasing the intensity of Likin by one standard deviation in 1910 (1.28) is associated with a drop in the population level by 7%. Furthermore, higher initial fiscal capacity developed in the Taiping area (say, its one SD increase, i.e. 3) is associated with higher GDP per capita (0.2 standard deviations), higher shares of manufacturing (0.15 standard deviations), and higher human capital (i.e. and increase in schooling, 0.5 standard deviations, and reduction in mortality rate, 0.6 standard deviations). These coherent results offer support to the ‘Likin as state capacity’ hypothesis, and to the viewpoint of the importance of developing a strong fiscal system for long-term development (Besley and Persson 2009, 2011). The positive and widespread association with all key aspects of long-term development are especially impressive in light of the contrast between the contexts in the literature and our own – the literature emphasises the positive impact of external wars, but not civil wars, and here we observe similar effects from a large civil war. The literature emphasises the positive effects of fiscal centralisation (Dincecco 2015 Hoffman 2015), and here we obtain the novel finding of positive long-term effect of fiscal decentralisation (in the presence of strong agency costs in a very large country).

- Finally, we find evidence of complementarity between fiscal strengthening and land property rights, consistent with the conjecture of the complementarity between state and institutional capacities (Besley and Persson 2009).

We interact the post-war Likin intensity with our three institutional variables: Early Taiping areas, Late Taiping areas, and the distance to Nanjing. When compared with the control sample, the coefficients of Likin on GDP per capita and fiscal capacity today in the Early Taiping areas are positive and significantly more pronounced. When compared with the control sample and the Early Taiping areas, the Likin coefficients in Late Taiping areas on all key outcomes (income, fiscal capacity, the modern sector, and human capital) are all positive and much more pronounced.

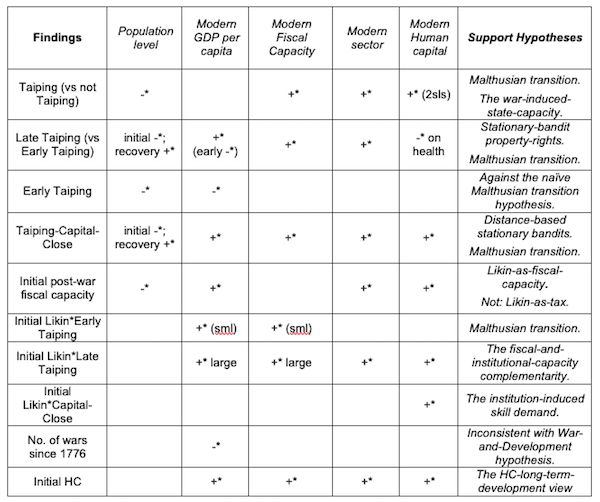

In this research, we offer evidence that the Taiping Rebellion, and the institutional and fiscal changes that were an outgrowth of it, affected the evolution of population levels, current incomes, fiscal capacity, shares of modern economic sectors, and human capital and continue to do so to this day. The rebellion facilitated China’s demographic transition from a Malthusian regime to a modern growth regime. Our findings support some of the prominent hypotheses in the literatures that examine long-term development and/or war and state capacity. Among these are that wars facilitate state capacity, big population shocks at times of significant technological changes facilitate favourable demographic transitions. Also, fiscal capacity and institutional quality are complementary, and a Malthusian transition and significant technological changes facilitate schooling in situations in which capitalists’ interest are well represented. Finally, human capital has key long-term development impact (see Table 1 for a summary of the match between our findings and the hypotheses).

Table 1 Summary of the match between our findings and the hypotheses

It also led to greater Western penetration and exploitation of China.

The role of Christian missionaries in fomenting the war has never been satisfactorily explained. It appears arguable that this was just the last of several attempts to put the Pope above the Emperor and it rather justifies Chinese reluctance, at least amongst those with a grasp of history, to allow Christianity the carte blanche it has always sought to form followings amongst the Chinese people.

So as regards Christianity, I would dispute your thesis

Very interesting, particularly the Likin effects. The word ‘capacity’ leads to some ambiguities. State capacity is the ability to administer its territory effectively, but the Likin decentralized state authority. Increased fiscal capacity spent how? Could this not be local land barons consolidating their rentier status?

This has some resonances with the AOC goes to Washington story. Early Taiping areas hung out to dry, Late Taiping doing well (and best for the few), and increased barriers to entry to the wealthiest areas.

可悲

Did they check if the late Taiping provinces were richer and more developed to begin with?

Because it seems that they were, with major urban centres like Hangzhou and Suzhou famous for their silk.

Also, speaking of confounders, both late taiping provinces are coastal whereas the control group contains both coastal and inland ones, and this alone could explain the difference in their post-European contact development.

Or maybe I missed this somehow.

(coastal cells can also initiate attacks against other coastal cells within a certain distance).

Tom Currie

It sounds like that China was doing the hard yards here. While fighting this civil war, they were also fighting the second Opium War against the British and French at the same time. Maybe that is why the British and French attacked during this period as China was being weakened. An oddity was that after the later war was over, British officers as well as some Americans, helped the Chinese Army put down the Taipings as they threatened the new British ports. I only know of this because of a British officer that had a prominent part in this army – Charles George Gordon – who those with a military bent will recognize as General Gordon of Khartoum.

Yes, most interesting was how the West ended up fighting alongside the Confucian reactionary forces instead of the West-leaning and Christian Hong Xiuquan. Because they could extract more rents that way

The western imperialists would’ve supported any side which was centrally administered. It’s hard to make political/economic deals with a coalition of independent warlords which is what the Taiping rebellion devolved to rather quickly. The warlords who supported the Qing dynasty wern’t entirely independent of Beijing.

It’s yet another reason why the imperialists supported salafism and sharia law throughout the Middle East. The whole development of Political “Islam” is ahistorical and ran contrary to the legal interpretation of the Koran at the time. The implementation of Islamic law was traditionally based upon a broad understanding of the Koran which gave local authorities a lot of latitude in how they governed.

This, of course, made it hard for western imperialists to dominate Muslim-majority areas. It’s ironic how that project came around full circle to bite westerners in the —.

I read he tried to get diplomatic recognition from Lincoln, but did not get it.

General Nivelle of the French army – think rolling barrage, the counter attacks at Verdun, the utter profligacy with French soldiers lives that led to the mutinies – cut his teeth there as a young officer.

The role of the British and French in putting down the Taiping rebellion merits forensic investigation

Nivelle was a toddler at the time. You are confusing with the Boxers rebellion.

Charles ‘Ever Victorious’ Gordon – he was known then.

The Taiping Rebellion, from 1851 to 1864, was the deadliest civil war in history.

So it beats Mao’s Long March (and then Giant Leap)?

das monde, I am fairly certain at least in terms of percentage of population killed the Taiping Rebellion was higher. Going solely on total numbers it might depend on whose estimate to use but I think even there the Taiping Rebellion is thought to have caused more deaths.

If you read The Cultural Revolution by Frank Dikotter it lays it out in gruesome detail. It’s the only book I’ve ever had to stop reading because it was so heartbreaking. People would sneak out in the morning to see what posters had been put up overnight so they could decide how to dress and act that day…or risk being butchered. In “The Four Pests” campaign people had quotas of the pests (mosquitoes, rodents, flies, and sparrows) they must kill and deliver every day. Instead of harvesting rice women sat on rooftops waving white flags because they were told that sparrows would die if they could not land anywhere. One province delivered 15 tons of flies. Meanwhile people were so poor they even sold their clothes. And their children. One family would hide naked in their house, one member would put on the last set of clothes to go and try to collect grass and spilled rice grains.

This all didn’t end until the mid-1970s, so very much still alive in current memory.

It’s been said that Chinese civil wars are world wars in scope. If the 70 million death toll of the Taiping Rebellion is accurate then it is comparable to World War II. The Three Kingdoms period of Chinese history similarly had a high bodycount of millions, or even tens of millions, of people. During this time the warlords and kingdoms which fought over the dominion of China embraced the concept of total war early on. Starvation and disease killed most of the civilian population as opposed to battle.

The Chinese Saint of War, Guan Yu (see the same in Wikiepdia), of the Three Kingdoms period is often portrayed to be reading Zuo Zhuang (the Commentary of Zuo) for the lessons of war from an earlier period – the Eastern Zhou dynasty, which is further divided into the Spring and Autumn period, and the Warring States period.

There, one can read about one million killed by one particular ‘effective’ general.

So, I would start from that time.

And after the Three Kingdoms period came the Wei dynasty and the Jin dynasty, whose royal members fled south when the Xiong Nu rebelled, ushering the Disunity period (or the North and South Dynasties). It is during this time that entire towns are said to be slaughtered for being the wrong ethnicity (the Hans would kill all the Xiabei people, the Tuoba to the Han, or any such combination). North China laid bare for a long time, as many Han people fled to the Yangtze delta area, which created many problems, one of which was how to take land from those in the south in order to give to the refugee aristocrats.

A few powerful clan families stayed and they helped the Xianbei to establish Confucian rule in order to harvest the resources. One such person was Yan Zhitui (from Wikipedia):

His ‘Family Instructions to the Yan Clan’ is very useful for studying those centuries in Chinese history.

The Taiping Rebellion may be the most deadly in terms of portion of the population that died, but the Washington post estimates 80 million died during Mao’s time, many during peacetime, of starvation, because Mao decided he knew how to make agriculture efficient.

That makes Mao the champion, and Hitler a piker with only 6M jews killed (ditto for Stalin and 7M Ukrainians). Ouch!

I believe the numbers you mention are now open to dispute by serious historians ? I don’t know enough here to have a decent opinion.

Lambert, thank you for this. It is not quite normal NC fare, so I wanted to make a particular point of welcoming it.

For anyone interested in the Taiping Civil War, I recommend Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War by Stephen R. Platt. I listened to the Audible version, which was quite good.

1) Another effect of the Taiping Civil War was that in the Meiji Restoration, Japan pretty much copied the program that the Taipings wanted to carry out. This also means that if the Taipings had won, China might have basically skipped to where it wound up with Deng Xiaoping’s reforms.

Sometimes in history, it seems that a country has an obvious path to take, some social forces or other send it off in some other direction, but after all is said and done (and with hideous loss of life), it winds up where it was meant to go all along. In the 1920s, Gustav Stresemann, who was the head of the Weimar Republic for a time, proposed a program under which Germany would not emphasize its military but would thrive through advanced industrialization and economic integration with the rest of Europe. This is where Germany wound up in the 1950s.

2) There is a connection between the Taiping Civil War and the US Civil War. The U.K., the world’s dominant power at the time, refrained from backing the pro-slavery rebellion in the US, at the short-term expense of some British commercial interests, but politically could not turn them down when it came to China. That is the short-term reason that the British backed the Qing against the Taipings (and delayed necessary changes for decades).

3) The extremely high death tolls are sometimes the product of someone comparing the population after the calamity with where the population growth seemed to have been heading. When this method is used, often deaths are mixed together with births that maybe would have happened but did not. For demographic purposes, that comparison is meaningful, but as an index of human suffering, not as much so.

This is particularly notable for the An Lushan Rebellion, which Steven Pinker and some others claim killed one sixth of the population of the entire planet. So the death tolls of most of the worst human-caused calamities need to be accompanied by a large plus/minus.

I take issue with a lot you’ve said, so in no particular order… The Chinese had many more opportunities to pursue modernization both before and after the first Sino-Japanese War that failed. The Meiji Restoration was a political plot to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate. It wasn’t primarily about modernization and westernization.

Stresemann’s idea was a much less ambitious duty-free union between Germany and Austria as opposed to the EEC/EU. France bitterly opposed this proposed plan, but it probably would’ve collapsed during the Great Depression anyway if the French hadn’t killed it.

That’s only obvious when you’re projecting your ideas into the past from the present.

That is part of what makes history history. People can have quite different interpretations.

In “Defying Hitler”, the author/narrator says that Stresemann’s vision toward the end of his career, shortly before he died, was a Germany based on its industrial prowess and free trade not on its martial prowess. You are correct that both France and the Great Depression (and the way that leading nations turned toward more autarky in response) meant that he could not have succeeded.

Yes, the Meiji Restoration in the narrow sense was a change of government in 1868, but the purpose of that change was to modernize in order to meet the challenge from the West that Japanese leaders were quite aware of.

Yes, China had other chances to modernize after the defeat of the Taipings, but the Qing were not able to take any of them precisely because they were the status quo.

General Bai Qi (see Wikipedia) is said to have killed 1 million or 2 million in total.

No one really knows and the numbers in ancient texts could be simple exaggerations (or the reverse).

Al the foreigners in Guangzhou (present day Guangdong) were said to have been killed by Huang Chao (who lived during the Tang dynasty). Did that really happen?

And when one of the two rebel leaders, who sacked Beijing and forced emperor Chongzheng to hang himself, moved into the Sichuan, he was said to have empties the province of its inhabitants, and when peace came later, the Qing government encouraged migration from Hunan/Hubei and Guangdong/Guandxi to repopulate it. Was it really empty?

The historical, and let’s be honest mythological, texts that survived can be compared to tax records from that era. In many cases so they are definitely exaggerations yet the result of the shifting in balances of power that yielded population displacement, forced or voluntary migration, starvation, and death from disease nevertheless contributed to an unprecedented body count for that period of ancient history.

At around the same time as the Taiping Rebellion, there was a couple other major rebellions – the Nian Rebellion, the Dungan Rebellion, etc.

The Dungan one, in particular, according to Wikipedia,

The British empire, the Ottoman empire and the Russian empire were also involved in supporting various participants.

How much of what led to the rebellion still lingers today, when we read about Uighurs in China?

You should also look at Peter Turchin’s analysis of the rise and fall of kingdoms and empires. He emphases the role of elites, how their greed drive regimes into overshoot and collapse, how these elites eventually suffer big losses themselves (not just the people), enabling the start of a more vigorous and less corrupt regime based on a more egalitarian spirit (asabiya). Until the cycle starts over again.

I found this article to be an unhappy mix of Western economic thought (Malthus’s theory on population and economic growth…just what is a Malthusian Transition?, and yes, I googled it, Yves is correct about the current state of affairs with Google search), statistics thrown in from left field (standard deviation, what standard deviation? just where the heck are these numbers coming from?), and selective historical cherry-picking of events (as pointed out by other commentators, China was engaged in several wars over this time, don’t they count?), all massaged into that cool, calm, ‘this is just science’, Paul Samuelson’s dicta of economics, circa the 1950s.

Bah, humbug!

The Qing also continued the process of granting further influence to the foreign concessionaires, in return for their aid against the rebellion.

For a less Malthusian interpretation of Chinese history, see Arrighi’s Adam Smith in Beijing.