Yves here. A lot of economists, like Paul Krugman, are arguing that the Bank of England’s Brexit forecasts are too dire, in Krugman’s case using trade models. I suspect he hasn’t looked at the 3 Blokes video or similar material to understand the real economy impact of Brexit will entail knock-on effects, particularly in a crash-out scenario.

By Kanya Paramaguru, a PhD student at Brunel University London. Her current research focuses on using empirical time-series methods in Macroeconomics. Originally published at Economic Questions

As the UK embarked on Brexit, economists were given a range of opportunities in which to provide some guidance as to how the tricky process of Brexit was going to go. A sub-discipline was entitled ‘Brexinomics’. This article looks at a tool used by economists, known as scenario testing and questions the reliance on this tool to navigate us through Brexit.

On June 23rd 2016, the UK decided to travel on the unknown road ahead known as Brexit. Economists were called on to provide some navigation for policy makers, the markets and businesses. The task was (and still is) to provide policy makers with how the economy will react either a ‘hard Brexit’, ‘soft Brexit’, or any kind of new rearrangement with the EU.

The Treasury and Bank of England have the most influential roles when it comes to acting as an economic advisor to the government. One of the methods that has been particularly relied on by these organisations is referred to generically as scenario testing.

What Is Scenario Testing and What Can It Actually Tell Us?

Scenario testing is a broad term given to the use of economic modelling to predict how a certain event is going to impact the rest of the economy. Analysts aim to predict the future impact on the economy arising from any-one number of things. Scenario tests are predominantly conducted using a global econometric model that contains large amount of data and equations that aim to describe the behaviour of the economy. These models are used by governments and central banks alike.

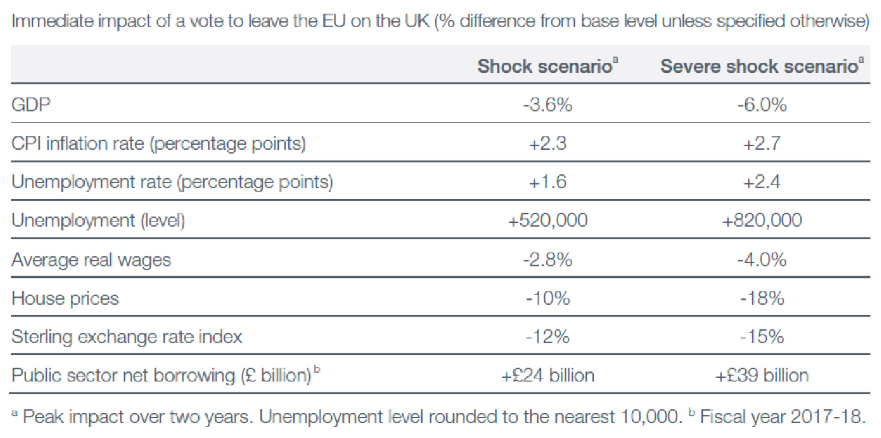

Since the announcement of the Brexit Referendum, scenario tests have been frequently referred to in news articles and senior politicians alike to provide a picture of what a post-Brexit world might look like. In 2016, the HMT published a document titled ‘HMT analysis: The immediate economic impact of leaving theEU’. In this document, they published the table below in which they outline the response of the economy to a leave vote in the referendum.

(Source: HM Treasury)

(Source: HM Treasury)

There are two shock scenario responses listed. These refer to a moderate and severe response of the economy to a leave vote in the referendum. The table shows that in the year following a leave vote 17/18, the economy is expected to contract by around 3.6%. In the severe case it is listed as -6% which would have been worse that the financial crisis of 2009 in the UK which saw a peak decline of -4.2%. In 2017, year growth on change was actually 1.7% (Office of National Statistics). That is a marked difference from the projected values.

This reveals that scenario tests are not suitable to handle something like Brexit, and their poor performance in outlining the economic effects of a leave EU vote is unsurprising.

A better use of scenario tests is to look at the overall impact on the economy of specific one-off economic events or policy changes, like a change in oil prices. A change in oil prices would typically start with changes in the income for oil-exporting countries and rises in costs for oil-importing countries. For the oil importing countries, the initial increase in oil prices would then lead to an increase in inflation as the cost of production increases. These different impacts can be modelled by scenario tests and they can provide a scale of the final economic impact owing to an initial increase in oil prices.

However, the number and scale of policy unknowns in Brexit means that a scenario test is always under-identified. We are dealing with infinite number of policy unknowns.

This leads on to the second issue with scenario tests is that they work under the assumption of ceteris paribus. This assumption is that all other things will remain equal during and after the specific economic event that is being analysed has occurred. With something like Brexit, there is no ceteris paribus, as all other things will not necessarily remain equal.

Brexit has the possibility of creating restrictions on migration, along with restrictions on trade and restrictions on capital flows. These could all happen simultaneously. Even if a scenario test could adequately model each of these events on their own, it is not able to consider interactions between different simultaneous policy changes. It seems unlikely that previous data could be used to show us what would happen in the event of all three of these policy changes simultaneously occurring given that this is not something that has occurred before.

Despite all these shortcomings, there is still often reference in the media to results of scenario tests conducted by key organisations. Scenario tests still seem to be providing some comfort in predicting what a post-Brexit world might look like.

There are two amendments that economists need to make. The first is to limit the scope and expectations of what previous data can tell us. Given the unprecedented nature of Brexit, it seems that historical data might not have the information to show us what could happen in the event of any kind of Brexit deal. It unlikely to accurately provide a percentage point increase/decrease in GDP in the case of any type of new arrangement with the EU.

The second amendment, is to move on from the empirical macroeconomic models and look at methods that will provide a truer reflection of how individuals might behave in response to the new arrangement with the EU.

What Are the Alternatives?

There have been already a number of surveys conducted that ask individuals and businesses alike, what they would do in ‘Brexit-like’events i.e. a restriction on migration leading to labour shortages. Piecing together information from macroeconomic surveys is more likely to provide a truer picture as it will give us actual behavioural responses from economic agents.

Seems obvious. Brexit is either a first, or a unique, event.

I suspect that Kanya Paramaguru, no matter how good she is on a computer modeling economics, could do with a few beers down at a pub asking people like the three blokes their thoughts on Brexit as suggested by Yves. I’m not sure how you can model an event like Brexit. I only have a vague nodding acquaintance with the methodology used but I’m not even sure that you can use empirical time-series methods to study this problem. Imagine using that to study the weight and well being of a turkey to just up to Thanksgiving when a different trajectory comes into play. The only one that comes to mind is the effects on Iran since Trump trashed that treaty and all the economic ills that have since ensued. Take out the bit about being chopped off from the SWIFT network and I think that you would have a more fair analog of what may happen to the UK’s economy in 116 days time with Irans imposed semi-isolation and difficulty in trading with other countries. As for the predictions of economists and their worth, I am reminded of the Story of the Old, Empty Barn-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qr_v_SqJNjA

The one thing certain about ceteris paribus is that it is a linear assumption or nearly so for cases in which equilibrium can safely be assumed (which Keynes and Fisher both reject). Brexit will be anything but linear and equilibrium in the EU would be a naive assumption. Other countries will surely leverage the UK’s woes to their economic advantage. How do you model that?

The unknown disturbance terms in the equation are indeed too numerous to model. Assuming equilibrium in the case of hard Brexit would be a case of dumber and dummerer. That is because economies are dynamic and thus require a well-identified dynamic model that can project out 5 or 10 years – including shocks and changes in equilibrium. I am unaware that such a model exists for any national economy with global interdependencies.

That May has been reassured by Trump’s promise of US trade support is about as ridiculous as Charlie Brown trusting Lucy Van Pelt with the football. Fascists lie.

The linear HMT model referenced in this article predicts dire outcomes, it is reasonable to anticipate that any substantial nonlinear events might make those negative data look tame by comparison – unless that event is the Second Coming.

What’s also missing from all these scenarios is a micro analysis from consumer upwards to small business, to corporates (and then back to consumers again and looping in workers).

Friction at the border and increased planning costs affects importers and exporters – drives prices up.

Those businesses unable to pass on or absorb the increased costs, fold. Their staff lose their jobs.

That ripples out through the economy from exporters first (assuming the UK relaxes import rules to avoid shortages and keep the lights on).

The zombie companies will go first. Then lending criteria will tighten.

Business planning will increasingly turn to survival, not growth.

The point about micro analysis is that one failure will ripple out in the myriad supply chains and cause a wave of stress.

I don’t know what the “six degrees of separation” rule is for businesses, but that would be fascinating to find out.

The Bank employs a network of people who operate as economic intelligence agents, talking to businesses in the different parts of the UK. I would imagine that they have been busy talking to businesses about the implications of a crash out Brexit pretty much since 2016. They will have gleaned a lot of what may be largely impressionistic information but what they say will almost certainly be better informed than any input their critics will have obtained.

Thank you.

I agree.

Also, senior Bank officials, including the governor and chief economist, often “go on tour” in June and July, addressing local chambers of commerce and other business fora. The ones in Northern Ireland, usually in the evening, are considered especially “liquid”.

In addition, summaries / surveys are provided by trade bodies etc. I was not involved when at the bankers’ association, but compiled monthly reports for the Bank when at the asset managers’ association. Scenarios like Brexit and Scoxit featured.

I went to Brunel. I agree with Yves and Kev about the author needing a reality check. My first degree was in law. My masters involved economics / political economy, including a dissertation on central bank independence (published in 1995, which I hope to update post 2008 into a doctorate). Most of the economists at Brunel were foreign, and still are, and unlikely to meet real people / Brits.

I should have added that Labour proposes moving some Bank operations to Birmingham, so that it feels / becomes less London / south east centric and may be get a feel of what’s going on.

Perhaps, the Bank could do worse than buy back its former Branch on Fleet Street, now the Old Bank pub, but retain it as a pub.

Colonel, where was your dissertation on bank independence published?

Thank you.

Brunel University, 1995.

Funny old World CS, first degree Politics & History, followed by Law at Leicester Poly and then back again to Uni for a Politics MA, my dissertation was focused on the Labour Party’s post 1945 Administrations relationship with Europe and drivers impacting this relationship, notably Marshall aid and the Sterling Zone (finished in 95) – I’ve got an offer to do a PhD in Political Economy, just a shame my finances mean I’m unable to act on it.

Thank you, CDR.

I have not forgotten to contact you on Linked In.

I have been away recently.

I do hope you can do the doctorate.

Your masters sounds fascinating. At Brunel, we compared how the big three countries in western Europe recovered from war and went about rebuilding their economies / societies and alliances. You work would have been invaluable for us students.

I would like to address how central banks have evolved since 2008 and how they should become accountable. I disputed then and dispute now that central bank independence is any form of panacea. Labour MPs Peter Hain and Roger Berry and the Guardian’s Larry Elliott helped me at the time. So did, Nigel Lawson.

CS,

Again, a funny old World, I was pushing you with regards a Central banking bash I’d hoped to arrange on behalf of McDonnell and his team, Steve Howell was assisting with this – suffice to say we ain’t got very far presently, but hope remains and our usual friend at the BoE was on my radar.

As for my own little MA dissertation, I took a little longer than usual with this due to health issues, my Politics Professor being a great person to work with – at the time, 1994-95, a lot of classified documentation was coming out regarding the Information Research Department (IRD) and some of its antics, which were quite shocking given we had a Labour Government overseeing its work – that said, Ernest Bevin was totally anti-Communist, but its actions in France, Italy and Greece were eye openers and all related to the UK combating both the Communist threat and gaining leadership of Europe – it actually was Sterling Devaluation that put pay to this notion, the rest as they say is History.

Thank you, CDR.

Good stuff!

Also and further to your recent comments about the gilet jaune insurrection across the channel, I wonder if alternative economists et al will emerge / be given MSM air time and perhaps engage with Labour and / or Momentum.

Chat soon.

Author here. I was born and brought up in London.

This seems like a weak criticism given that multivariate analysis is used to handle exactly this scenario. (Unless she is saying that economists don’t understand multivariate analysis, which is sadly more plausible than it ought to be). Or perhaps there is not enough data available for this kind of analysis.

Personally I think I would start by looking at it from an engineering and logistics perspective, look for tight couplings and critical dependencies, and analyse the possible consequences and outcomes if those were to come under strain or fail entirely. A central assumption of most economic analysis is that markets perform at least somewhat efficiently, and that simply won’t be the case here, at least in the no deal scenario. It will be a step transition, and models have a way of breaking down in those situations. Go and look at waves breaking at a beach for an example. What good will economic models do if Dover becomes a massive parking lot?

Economic analysis also likes to pretend that politics doesn’t matter, which simply won’t be the case here. Take flights. Will they be grounded or won’t they? If they will, for how long, and what will the resolution be? That question obviously has enormous implications on any predicted economic outcomes, and it simply doesn’t sit within the economic realm to answer. There will be hundreds or thousands of other decision points like it, at all scales and degrees of severity, and all requiring policy action to resolve. So your choices are to try and effectively model the underlying dynamics and assess the range of possible outcomes (good luck!) or find similar cases from history and reason by analogy.

One ‘unknown’ is the suspicion that relatively healthy growth the past few months has been due to manufacturers stockpiling – . Even in entirely normal circumstances, this could lead to a recession if they all find they have too much stock on their hands and simultaneously many cut orders.

Another issue which I think is impossible to model is how forebaring banks and other creditors will be if the disruption to cash-flow means many small to medium businesses are temporarily unable to service loans, or need bridging loans to keep their employees paid. No doubt a lot of pressure will be put on banks to be co-operative, but they may be under their own strains. In the last crash a lot of UK banks operated in an extremely predatory manner on some of their customers.

Thank you and well said, PK.

Your last sentence is particularly spot on. There was a suggestion going around the City that banks should target vulnerable companies with good assets, including luxury hotels and private jets, so that banksters could use these (assets / facilities at a discount, if not for free) until they had been sold after a “work out”. My employer still gets “mates’ rates” at the hotel and casino complex it owned in Las Vegas.

This predation will fit well with the disaster capitalists waiting in the wings.

Or to pay their rent. So forbearance from landlords also needs to be gauged.

These issues are the nuts and bolts of doing small business in Britain, and the evidence is that forbearance will be zero. Landlords have to worry about capital valuation, and banks just optimize their take, as shown by the ongoing scandal over RBS treatment of business customers who went into default from interest-rate swaps.

I thought this might be interesting to readers. This is an interview with Leftist author Richard Seymour* in March 2018. A lengthy excerpt gives one a glimpse of the UK Labour Party factions and how Corbyn and the party are trying to position themselves with reference to the UK business community. Seymour isn’t an “expert” on Brexit, but no one will be a complete expert for many a year to come. The UK’s entry into the EEC back in the 1970s was taken in part to create a more stable economic environment within an already well established trading block. The UK jettisoned other trading relationships, such as with Australia, in order to gain advantage. This seems to have worked to some extent. Leaving the EU is a totally different game with too many unknown unknowns to make anything other than broad projections.

As Yogi Berra so presciently said: ‘It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.’ But even in a capitalist society people need to make plans and that requires creating coherent views on the range of possible outcomes one might expect in the future.

Anyhow, regarding how business might theoretically react to Brexit in the event of the hard option being taken:

“…There was always a prospect that business would start to engage in an investment strike or to withdraw capital from the economy, particularly in the city of London. However, with the Conservatives defending a hard Brexit that almost nobody in business actually wants, Corbyn has allowed his allies essentially to lead him into a position where Labour is more sensible for business in principle than the Conservatives. Now, of course, that’s always contingent on a whole series of other things. There are many things about Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour that business still doesn’t like, but in terms of the policies regarding investment in the infrastructure, borrowing to invest, business is in favor of that. Business is in favor of investing for a new railway network, investing in green technologies, all of this stuff.

So, this is not a hugely radical program in historical terms. It’s just that there hasn’t been the experience of particularly a left wing government delivering these policies before and they don’t trust him. To some extent, he’s had to negotiate these changes, but the other side of it is that the right wing of the Labour Party, particularly the Parliamentary Labour Party, was always going to apply some pressure on him on this question. On the one hand, you have the sort of fairly conservative nationalist right wing of the Labour Party, and on the other hand, you’ve got the sort of Blairite rights who are very pro-market, very pro-EU. And then beyond that is sort of the soft left position, which is also pro-European Union. Corbyn has been under a lot of pressure from those different forces. What you see here is a kind of compromise and probably the only one that he would ever have reached…”

https://therealnews.com/stories/the-brexit-dilemma

*Seymour is a radical marxist – radical in that he has left all current socialist formations and is looking from the outside, so to speak, and taking stock. He has addressed the Momentum wing of the Labour party. I’ve come to the conclusion those that who currently call themselves radical rarely are – in either the right or left.

@makedoanmend,

Yves, and this site in general, that’s the commentators, have been quite good at detailing the many mistakes the UK Elite have made since the Brexit vote of 2016, the first being a belief that the UK had an actual hand to play in all of this, closely followed by the fact that instead of planning for a ‘siege economy’ from Day One, which actually may have strengthened the UKs negotiating position, they did the reverse and thought a deal could be negotiated that would appease both Leave & Remain voters.

Indeed, those of us lucky enough to have known those who survived the Great Depression and actually listened to their insight, would be under no illusions, however, hubris in the UK’s Ruling Elite does seem to feature, as does living in a fantasy world quite divorced from the average Joe.

Indeed, the passing away of the Depression/War era generation has been cited by many as paving the way for the deleterious effects we all feel as a result deregulation and so forth. That generation understood in a concrete way that certain checks and balances were required in order to make society function better. There was a pretty common, although by no means universal, idea that there was a necessity for levelling factors.

As a Bsc. student, having done a B.A. back in the stone ages, I see a profound change in academic culture and a diligent replacement of old lecturers who had a diverse wealth of experience. Their departure, so we are told, is apparently done to improve profit and efficiency, as if that is the mission of an educational establishment.

In fact, I have come across neo-lib politicos at home that brag about the need to get rid of older people in organisations so that new entrants are not “polluted” by old ideas.

Thank you.

Seymour also wrote this https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/02/opinion/northern-ireland-brexit-unionism.html. I read it when published by a Middle Eastern newspaper and in that region on business a month ago. Colleagues could not imagine that the imperial presence that is / was the UK is fading and how quickly things have fallen apart / broken down since the referendum.

Yes, I tend to like Seymour’s work, though he was a bit too erudite at times in his public writing, but that is to be expected from someone who was doing intense study for his PhD.

I especially like that he left the former dead-end socialist formation of which he was a member. It seemed to free him up to take stock of a wider range of issues. Mind you, he’s not to everyone’s cup of tea, but hey ho.

I kind of categorise him as a return to the more radical roots of 18th Ulster Protestants that looked beyond the confines of their class and religion to analyse bigger ideas and implement more wide ranging reforms in other parts of the world. Hope he can help influence policy in the UK Labour Parry.

Just adding my own two Bob’s worth here, but Brexit really has been a Black Swan, which no one has yet commented upon, and the dynamics at play following nearly 50 years membership of the EEC/EU are so large that its almost impossible to give any meaningful measures too. That said, Prof Steve keen may be able to provide a model and I’m aware one of his Phd students from Portugal has managed to Model his home country’s economy to a degree never managed previously – Keen has great hopes for this person.

I finally got around to watching the 3 blokes video (takes an hour) – very educational for this yank.

As Yves might put it: Wowsers!

Looks like Brexit could be rather, uh, messy.

So after reading this post, I finally took the time to watch the Three Blokes.

It strikes me that it was the present economic value of the entire history of the institutionalization of agreements to cooperate commercially, the cultures and physical structures and infrastructures that grew up around them and the secondary institutions that evolved to address the changes necessary in these systems due to the contingencies of time that Joan Robinson was arguing Solow and Modiglioni were ignoring in their arguments in the Cambridge Capital Controversy: this is exactly what the Blokes are describing.

I admit I couldn’t follow the mathematical intricacies of her argument, so I’ll be happy to be disabused of my misunderstanding if I’m wrong, but Brexit looks like an apocalyptic instance of “assume a can opener”!

ChrisPacific above makes the main point. This is about politics, full stop.

Attempting to evaluate it in economic terms is at least in part as meaningful as a discussion about the smell of colours.