By Enno Schröder, Economist and Servaas Storm, Senior Lecturer of Economics, Delft University of Technology. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Sounding the Alarm on Global Warming

If the Paris climate agreement of December 2015—the so-called COP21 —provided cause for optimism that, after years of fruitless diplomatic squabbling, coordinated global action to avoid dangerous climate change and ensure manageable warming of less than 2° Celsius, would finally happen, recent publications by climate scientists are loudly sounding the alarm bells. Specifically, Earth systems scientists (Steffen et al. 2018) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC 2018) warn that even if global emissions are drastically reduced in line with the 66% below 2°C goal of COP21, a series of self-reinforcing bio-geophysical feedbacks and tipping cascades—from melting sea ice to deforestation—could still lock the planet into a cycle of continued warming and a pathway to final destination: “Hothouse Earth.”

Allowing warming to reach 2°C would create risks that any reasonable person—if not, perhaps, Donald Trump—would regard as deeply dangerous. To avoid those risks and keep warming below 1.5°C, humanity will have to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs) to net zero by 2050. The early optimism about the Paris agreement is giving way to widespread pessimism that COP21 will not be working soon enough. Climate scientists and Earth systems scientists attempt to counter the growing pessimism by showing that limiting the global mean temperature increase to 1.5°C is neither a geophysical impossibility, nor a technical fantasy. The engineering solutions to bring about deep de-carbonization—including quick fixes and negative-emissions technologies—are available and are beginning to work.

The real problem is that available solutions go against the economic logic and the corresponding value system that have dominated the world economy for the last half decade—a logic aimed at scaling back (environmental) regulations, pampering the oligopolies of big fossil-fuel corporations, powering companies and the automotive industry, giving free rein to financial markets and prioritizing short-run shareholder returns (Speth 2008; Klein 2014; Storm 2017). Hence, as Steffen et al. (2018) write, the biggest barrier to averting going down the path to “Hothouse Earth” is the present dominant socioeconomic system, based as it is on high-carbon economic growth and exploitative resource use. We will only be able to phase out greenhouse gas emissions before mid-century if we shift our societies and economies to a “wartime footing,” suggests Will Steffen, one of the authors of the “Hothouse Earth” paper in an interview with Kate Aronoff (Aronoff 2018).

…But Don’t Panic. Don’t Panic!

The alarmist tone of the “Hothouse Earth” analyses stands in contrast to more upbeat reports that there has been a delinking between economic growth and carbon emissions in recent times, at least in the world’s richest countries. The view that decoupling is already happening in real time is a popular position in global and national policy discourses on COP21. To illustrate, in a widely read 2017 Science article titled “The Irreversible Momentum of Clean Energy,”, former U.S. President Barack Obama, argues that the U.S. economy could continue growing without increasing CO2 emissions thanks to the rollout of renewable energy technologies. Drawing on evidence from the report of his Council of Economic Advisers (2017), Obama claims that during the course of his presidency the American economy grew by more than 10% despite a 9.5% fall in CO2emissions from the energy sector. “[T]his ’decoupling’ of energy sector emissions and economic growth,” writes Obama, “should put to rest the argument that combating climate change requires accepting lower growth or a lower standard of living.” Obama is not the only optimist in town; others have highlighted similar trends:

- The International Energy Agency (IEA) argues that global carbon emissions have decoupled from economic growth from 2014-16 (IEA 2016); the IEA 66% below 2°Cpathways are based on steady-state rates of potential output growth from 2014-2050 of 2% for the U.S., 1% for the E.U. and .5% for Japan (OECD 2017, p. 171);

- The World Resources Institute reports that as many as 21 countries (mostly belonging to the OECD) managed to reduce their (territory-based) carbon emissions, while growing their GDP in the period 2000 to 2014 (Aden 2016);

- The Global Commission on the Economy and Climate (2018) speaks about a “new era of economic growth” that is sustainable, zero-carbon and inclusive—and driven by rapid technological progress, sustainable infrastructure investment and drastically increased energy efficiency and radically reduced carbon intensity;

- International Monetary Fund economists Cohen, Tovar Jalles, Loungani and Marto (2018) find some evidence of decoupling for the period 1990-2014, particularly in European countries and especially when emissions measures are production-based; and finally

- The OECD argues, in its 2017 report “Investing in Climate, Investing in Growth,” that the G20 countries can achieve “strong” and “inclusive” economic growth at the same time they reorient their economies toward development pathways featuring substantially lower GHG emissions.

In our new INET Working Paper, we attempt to go beyond the “Yes, We Can” optimism concerning decoupling, offering what we hope is a more realistic evaluation of the nexus between economic growth and carbon emissions. We do this in two ways. We first assess the viability of a long-run decoupling of global economic growth and carbon emissions using the easily-understood Kaya identity[i]. We then present a systematic econometric analysis of the (historical) relationship between economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions, using the Carbon-Kuznets-Curve (CKC) framework. We run panel data regressions using OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) CO2 emissions data for 61 countries during 1995-2011, and to check the robustness of our findings, we construct and use three other panel samples sourced from alternative databases (Eora; Exio; and WIOD).

Can the Global Economy Grow as Global Carbon Emissions Fall?

We first assess the scope for (global) growth from 2014-2050, which is consistent with carbon emission reductions of the 66% below 2°C scenario of COP2. Using the Kaya identity, the growth of global carbon emissions can be decomposed into global population growth, per capita income growth, the growth of carbon intensity of energy supply, and the growth of energy intensity of GDP. Table 1 presents the results of a decomposition of global CO2 emissions for the period 1971-2015 and our projection for the period 2014-2050. Note that we focus on CO2emissions from the energy system, which represent 70% of global GHG emissions in 2010. As Table 1 shows, historically, global CO2 emissions increased by 1.93% per year during 1971-2015. Growth in population (at 1.53% per year) and in per capita real GDP (at 1.91% per year) exerted upward pressure on CO2 emissions, which was only partially offset by downward pressure from higher energy efficiency (energy intensity declined by 1.35% per annum) and lower carbon intensity (which declined by 0.15% per year). These downward trends in energy and carbon intensity are insufficient to delink economic growth and carbon emissions—and they are nowhere close to what is needed to achieve the longer-term Paris pledges or the recommendation of IPCC (2018).

Table 1: A Kaya Identity Decomposition of Global CO2 Emissions, 1971-2015 and 2014-2050 (Average Annual Growth Rates %)

| Actual Changes | Prognosis: 85% reduction in CO2 emissions | |||

| 1971-1990 | 1991-2015 | 1971-2015 | 2014-2050 | |

| global CO2 emissions | 2.05 | 1.89 | 1.93 | ─5.13 |

| world population | 1.80 | 1.31 | 1.53 | 0.79 |

| real GDP per capita | 1.75 | 2.14 | 1.91 | 0.45 |

| energy intensity (TPES/GDP) | ─1.08 | ─1.59 | ─1.35 | ─2.69 |

| carbon intensity (CO2/TPES) | ─0.40 | 0.06 | ─0.15 | ─3.68 |

Table 1 also presents our growth prognosis for the period 2014-2050. We assume that global CO2 emissions in 2050 have to be reduced by 85% relative to their 1990 level, or by 5.13% per year. World population growth equals 0.79% per year, based on United Nations projections. The very ambitious (i.e. historically unprecedented) projected decreases in energy and carbon intensity are taken from OECD (2017, Table 2.18); these projections are in line with IEA-OECD 66% below 2°C scenarios. Based on these optimistic assumptions, we find that climate-constrained growth of global per capita income cannot exceed a measly 0.45% per year during the next three decades. Hence, if we want to stabilize the climate, future global economic growth must be well below the historical annual income growth rate (of 1.93%) during 1971-2015—and this holds true under the optimistic assumption that we manage to bring about historically unprecedented reductions in carbon intensity and energy intensity.

The prognosis strongly suggests that we have reached a fork in the road. We could continue to grow our economies the way we did in the past, but this means we have to prepare for global warming of 3°C to 4°C by 2100 and run a big risk of having to adapt to “Hothouse Earth.” Adaptation would mean that we have to come to terms with the impossibility of material, social and political progress as a universal promise: Life is going to be worse for most people in the 21st century in all these dimensions. The political consequences of this are hard to predict.

But there is an alternative: We do whatever it takes to force through the technological, structural and societal changes needed to reduce carbon emissions so as to stabilize warming at 1.5°C (Grubb 2014; Steffen et al. 2018) and just accept whatever consequences this has in terms of economic growth (Ward et al. 2016). Whichever way, the bottom line is that the climate constraint appears to be binding. Or are we missing something: Is there a small group of (advanced) countries that have crossed the turning point of the CKC?

Can we put to rest the argument that halting warming requires accepting lower growth, as Obama argues we can? We systematically investigate Obama’s hypothesis that a small group of (advanced) countries has crossed the turning point of the CKC (Schröder and Storm 2018). The CKC hypothesis holds that CO2emissions per person do initially increase with rising per capita income (due to industrialization), then peak and decline after a threshold level of per capita GDP, as countries arguably become more energy efficient, more technologically sophisticated and more inclined to and are able to reduce emissions by corresponding legislation. We run panel data regressions using OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) CO2 emissions data for 61 countries for the period from 1995 to 2011. To check the robustness of our findings, we construct and use three other panel samples sourced from alternative databases (Eora; Exio; and WIOD). We present a variety of models, and pay particular attention to the difference between production-based (territorial) emissions and consumption-based emissions, which include the impact of international trade (Schröder and Storm 2018).

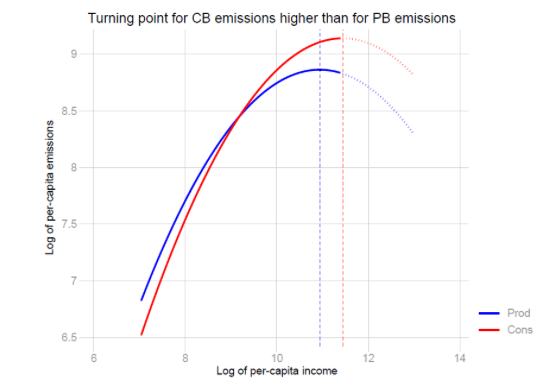

Figure 1 summarizes the result of our baseline regressions which provide evidence for the existence of an CKC for production-based CO2 emissions with a turning point at 56 thousand dollars per capita. If China developed along the path of our production-based CKC, it would exhaust half the global carbon budget before even reaching the turning point. Accordingly, global economic development along the production-based CKC is not compatible with the IPCC (2018) pathway consistent with keeping global warming below 1.5°C.

The turning point for consumption-based CO2 emissions is at 93 thousand dollars – outside the sample range. Hence, we conclude that while there is some evidence of decoupling between economic growth and production-based (territorial) emissions, there is no evidence of decoupling for consumption-based emissions. Some OECD countries have managed to some extent to delink their production systems from CO2 emissions by relocating and outsourcing carbon-intensive production activities to the low-income countries. The generally used production-based GHG emissions data ignore the highly fragmented nature of global production chains (and networks) and are unable to reveal the ultimate driver of increasing CO2 emissions: consumption growth. Obama is wrong, therefore: there is no evidence of carbon decoupling—and mind you, it is no great achievement to reduce domestic per capita carbon emissions by outsourcing carbon-intensive activities to other countries and by being a net importer of GHG, while raising consumption and living standards.

Figure 1: The Carbon-Kuznets Curve, 1995-2011 (61 countries) Note: Based on estimations by the authors. See Schröder and Storm (2018) for estimation results and checks.

A Realist’s Assesment

Our statistical analysis shows that, to avoid a climate catastrophe, the future must be radically different from the past. Climate stabilization requires a fundamental disruption of hydrocarbon energy, production and transportation infrastructures, a massive upsetting of vested interests in fossil-fuel energy and industry, and large-scale public investment—and all this should be done sooner than later. Steffen’s analogy of massive mobilization in the face of an existential threat is fundamentally correct. The problem for most economists is that it suggests directional thrust by state actors, smacks of planning, coordination, and public interventionism, and goes against the market-oriented belief system of most economists. “Economists like to set corrective prices and then be done with it,” writes Jeffrey Sachs (2008), adding that “this hands-off approach will not work in the case of a major overhaul of energy technology.” We thus have to discard the prevalent market-oriented belief system, in which government intervention and non-market modes of coordination and decision-making are inferior to the market mechanism and will mostly fail to achieve what they intend to bring about. Without a concerted (global) policy shift to deep de-carbonization (Sachs 2016; Fankhauser and Jotzo 2017), a rapid transition to renewable energy sources (Peters et al. 2017), structural change in production, consumption and transportation (Steffen et al. 2018), and a transformation of finance (Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018), the decoupling will not even come close to what is needed (e.g. Storm 2017).

Political support for such a strategy of deep de-carbonization is not in the cards—not just in the U.S., but also in Brazil, Australia, and elsewhere. Ostensibly more progressive “green growth” approaches unfortunately remain squarely within the realm of business-as-usual economics as well, proposing solutions which rely on technological fixes on the supply side and voluntary or “nudged” behavior change on the demand side, and which are bound to extend current unsustainable production, consumption and emission patterns into the future. The belief that any of this half-hearted tinkering will lead to drastic cuts in CO2 emissions in the future is plain self-deceit; and we know, with Ludwig von Wittgenstein, that nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself. Hence, if past performance is relevant for future outcomes, our results should put to bed the complacency concerning the possibility of “green growth.” There is no decoupling of growth and consumption-based CO2 emissions – “green growth” is a chimera.

See original post for references

So we just give up trying? The new way forward is to utilize the same old neolib ways of doing things that keep the corporate bank accounts full to the detriment of the world. The new American way.

So, you didn’t read the article?

Yes I did: “There is no decoupling of growth and consumption-based CO2 emissions – “green growth” is a chimera.” There can be decoupling if the will to make it so is there.

Yes, you’re right about the will to change, but what the article is about is the fact that the phrase “Green Growth” is being used by the usual suspects to do just the opposite.

The folks pushing ‘Green Growth‘, and by pushing, I mean defining its components, are dedicated to skirting the issue of decoupling from the carbon economy, and want us to fiddle around the margins instead of addressing the problem directly.

IMO, your argument should be with those who perverted the phrase, not with the author who points out the truth surrounding the term.

This really is a straight forward observation, it’s just like the US ‘spreading democracy’ really means bombing people who don’t look like us, and who have resources that we want to control.

While there are certainly profitable economic activities with very low carbon footprints (and even negative carbon footprints), they are not common enough to either beat climate change or drive the economy forward. We can’t expect 2-3% growth rates and drastically reduce our GHG emissions at the same time. It’s impossible. Even some on the left falsely believe that we can do this with a Green New Deal. While I support such policy anyway, it won’t be enough.

The only way we could reduce our GHG emissions in a way to stop climate change would be through a command economy (or eating beans instead of beef, but we know that’ll never happen). The author is correct that we would need to completely change our system of production, and that’s incompatible with our current capitalist system. And also entirely impossible politically.

All we can do is do the best we can and be thankful that we’ll probably be able to live most of our adult lives in relative normalcy. The end of the world probably won’t happen at least until we’re old, so we’ll still get our 80 years of so of life. We might die very sad knowing that our children and grandchildren will die out, but then we’ll fall asleep one last time and never wake up so it won’t matter anyway.

Thank you, John. And, it is your widely held belief, that 2050 actually means something, which means the masses won’t mobilise and demand change before its way too late.

We could probably adapt to 2 degrees, but in reality that 2 degrees will lead to abrupt and unexpected deadly weather. It already is. Some of these changes will be deadly to insects, birds and plant life, all of whom are less able to adapt to sudden temperature variations than are humans. A huge loss of biodiversity (200 species become extinct every single day) is something we cannot survive.

It will be our inability to grow food at scale which will end it for us. I am not making plans beyond 2 years.

Normal is gone now. Statements indicating that we have until 2050 to get this done are ludicrous. There can be, and must be, growth in the green area of the economy. But overall growth forevermore, the logic of the cancer cell, is over. Either as a result of really jarring change that we think through and impose on ourselves, or as the result of continuous monumental catastrophes. If I was a betting man, I would bet the farm on option #2.

Remember that a ‘use less’ solution, for many people, means you have no solution. Saves a lot of mixed communication.

Instead we get piss-ant neoliberal solutions such as Macron’s reduced taxes on the rich followed by a regressive fuel tax in the name of cutting carbon emissions. Leona Helmsley would be proud.

http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1891335_1891333_1891317,00.html

No econ whiz am I, but I do recall reading some stuff by Herman Daly that impressed me at the time, and IIRC, his views resonate with those expressed in this post. I am surprised that I have not seen him referenced more often on the topic of sustainable economic theory and practice.

Plants grow as part of nature, and they’re green. What do we mean by “growth” such that it can’t be green? It seems to be the growth of money, which is also “green” but not natural. Am I alone in thinking that we need to talk more simply and clearly about such things?

From the article above;

I don’t think it could be stated more clearly?

Also from the articles conclusions;

I think you’re arguing that “green growth” could work, which I would think, is true. However the issue this post addresses is that the same folks causing the problem are the ones proposing the details of “green growth”.

They’ve co-opted the language in order to control the discussion, so if we can come up with a better plan, we just have to avoid the “green growth” label that ‘they’ have stolen from us.

“What do we mean by “growth” ….”

That is the question! There has been some discussion here, and a while back at The Archdruid’s site, on the differing ways in which the dominant paradigm views ‘growth’ versus the views of Indigenous peoples.

We assume that growth has to be in a straight line, that there must always be more of everything. And, that more is better. Many Indigenous societies regard the process of life as circular: there is growth, flowering, fruiting, and then there is decay and death. And, some things wither away and die, but other things spring up to take their place. This is the way Nature works.

Further, there have been discussions on what GDP measures, is it a relevant measure, can another unit of measurement be created. So, now the unspoken assumption is that an increase in GDP equals an increase in happiness. We all know that this is not so.

Maybe we should be asking, as one asks at a crime scene, “cui bono?” Who benefits from keeping GDP as a measurement of ‘growth?’

Ok, my final question was dumb. We all know who benefits.

Plants grow and then die. There are no more plants (on the average) at the peak of this growth season than last year. This has NOTHING in common with the “growth” that economists and banksters are enamored with, in which the sum of everything gets bigger over time, at an ever-accelerating rate, with no limits. The latter is obviously a physical impossibility on a round planet. Climate change is just one of the “limits to growth” we are hitting.

(Funny, we argued over this same wording confusion a decade ago on The Oil Drum.)

Read Herman Daly’s writings for more about this and the only true alternative: a steady-state economy.

Naive question…

If a nation that controls its currency decides that de-carbonization is more important than GDP growth, does that effectively mean that all investment must come from the government? Does private money flee to nations where investment is more likely to grow XX%/yr?

Unrelated, but it is awesome to read a website that takes climate change so seriously. I would have went crazy if I was still getting news from NYT or similar. Thank you Yves, Lambert, Jerri-Lynn, and the rest of NC.

So true, Linden S. One reads the MSM business/economic news with all the talk of more auto production, additional airports, bigger tankers, more oil drilling and fracking and you get crazy. I want to scream and stamp my feet and yell, “Don’t you know what is happening to the Planet?”

Who will step backward, and become our green Pol Pot ..

That’s the inherent problem with every single solution. If it takes such a mass mobilization, coupled with such a change of thinking and suspension of our way of life (i.e. using fossil fuel vehicles across the board), it will take a Pol Pot to whip everyone into submission or else. This is what the right of center types already realize, which is why you could tell them that a ball of flames is coming to destroy the planet tomorrow and it still wouldn’t matter. Because to die free is more important than to live as a slave. So, something of a non-starter if you can’t get past the involuntary aspects of the global warming cures. The argument is inherently pro-totalitarianism and anti-humanist. Tough sell.

I wonder what the freedom they would die for even consists of, because I don’t see much freedom to begin with, only the totalitarianism of he who has the gold makes the rules, and all else well 2nd rule of neoliberalism. But they will die “free” or sacrifice their children and grandchildren in that inferno anyway. I wonder what younger generations think of them “dying free”. I doubt they will celebrate it as heroism. Then again they don’t seem very susceptible to the “freedom” argument anyway.

I disagree with your assertion:

“The argument is inherently pro-totalitarianism and anti-humanist.”

What humanism is there in Neoliberal economics? How totalitarian has our Neoliberal Corporate State become? Instead of eugenics feeding concentration camps we have the Market feeding poor into the streets to die a slow death. A government working toward the common good may trample on the freedom of the wealthy to skin the rest of us but there is nothing inherently totalitarian or anti-humanist about our government working to save what can be saved of our society.

Wasn’t that kind of how the New Deal thing worked? Though of course a wonderful enterprise opportunity, that WW II, did the kind of creative destruction that has in no small way led to where we are…

And not to worry, there’s life beneath the planet’s skin, in deep caves or in the “living rock” itself, and as one “conservative” told all us “apocalypticists” concerned about the self-created threats to our survival, “Chill! If you all die, there will be the tube worms that live on sulfur and iron at 250 degrees Centigrade, down there three or four miles in the ocean where the volcanic vents exit the crust! Life will go on!”

If we’d mobilize for war — and the nation state model sort of expects that — why would we not mobilize to avert a serious crisis?

+1

So well put I’m working on stealing it for my own uses.

It should be blindingly obvious at this point that there is no appetite among average people (voters, workers, consumers) for making sacrifices to ameliorate carbon changes. (There is no appetite among elites either, except to the extent the sacrifices are made by others.)

This means unless we find one or more technical fixes we need to accept that the world will be 2.5C or more warmer and plan accordingly.

In terms of technical fixes, if you want to drastically reduce fossil fuel emissions right now (given the no sacrifice constraints), you should be building nuclear power plants. Lots of them. Among liberals and environmentalists, that position is broadly unacceptable (which leads to the inescapable but unpalatable conclusion that they also are not entirely serious about climate change).

Solar and storage technology continues to improve however so things are not hopeless; but scientific progress doesn’t arrive on a set schedule. Should we invest billions extra in this sort of research? Sure. Will that help mitigate climate change? Probably/hopefully. Will it guarantee us a reach of any particular target? Nope

(which leads to the inescapable but unpalatable conclusion that they also are not entirely serious about climate change)

Um, no it does not.

“It should be blindingly obvious at this point that there is no appetite among average people (voters, workers, consumers) for making sacrifices to ameliorate carbon changes.”

I don’t think it’s remotely obvious at all, people vote for environmentally beneficial policies even sometimes at sacrifice (mostly on the local level because the Fed gov, well you know …). I think it’s undetermined.

“This means unless we find one or more technical fixes we need to accept that the world will be 2.5C or more warmer and plan accordingly.”

everyone should have a plan to end their life on their own terms, if need be, under the conditions we will probably get it will quite likely be desirable.

“In terms of technical fixes, if you want to drastically reduce fossil fuel emissions right now (given the no sacrifice constraints), you should be building nuclear power plants. Lots of them.”

that seems like a solution from 20-40 years ago, that might have worked then, but now it may be too late to make any sense. Because now we need to figure out how to protect any existing not to mention new nuke plants from rising sea water, increased storms and flooding and hurricanes, increased fires etc. etc.. – ie the reality of climate change. And I don’t think we have, and until we discuss that seriously I’m not sure planning yet more nuke construction makes any sense.

If it’s too late today for the nuclear solution, then it’s too late for any solution. We can’t get there on renewable power. It would take 20 to 30 years just to build enough renewable power generation to provide enough TWh per year, but when you add in the need for MASSIVE energy storage systems so that energy is available when it’s needed even during periods of unfavorable weather (e.g., hot summer days after dusk and most winter nights), the exercise would take a hundred years and would be many times as expensive as the nuclear solution.

Could we get there by people making sacrifices? I very much doubt it. People are certainly willing to make minor sacrifices (turning down the thermostat, using LED lighting, driving a more economical car), but that’s probably only enough for a 20% improvement. Alas, the IPPC says we need an 80% reduction. To get to 80%, we’d need for most people in rural and suburban communities to abandon their single-family homes and cars and move into well-insulated block housing in the city where they could use public transportation.

And that important to note. Those houses and cars must be abandoned. To sell them to somebody else who would continue to use energy in them defeats the purpose. Do you really think 150 million Americans would be willing to make that level of sacrifice? And would there be enough places in the city for them all to live anyway? It’s be the largest mass migration event in all of American history. And to do it in 12 years as the IPPC suggests? There’s no way.

If you are aware of any initiative covering more than 2,000,000 people which actually reduced (not outsourced) carbon utilization by 10% or more in the last decade, I’d be cheered to here of it.

At least in the United States, protecting nuclear power plants from flooding, major storms and rising sea levels is relatively easy.

People who oppose nuclear power aren’t serious about climate change?

A few thoughts:

– nuclear power plants produce nuclear material that humans are not safeguarding well during the plants’ operation, and not storing well after the plants’ life span is over. When societies break down, from internal or external wars, resource exhaustion, or whatever, nuke plants will meltdown like Fukushima, each one a massive firehose of radiation that will last millennia, toxifying the entire planet more than it already is. After a social collapse, the hundreds of nuke plants in existence will have far less tender-loving-care than Fukushima got. A coal plant or oil plant or solar farm, on the other hand, if humans just walked away from the plant one day, wouldn’t cause nearly so much global harm. I’m not supporting these other things, just acknowledging their benefits over nuclear.

– nuclear power plants also seem related to the spread and production of nuclear weapons, another nuclear damocles sword over the earth..

Instead of focusing on massive, high-cost, high-complexity high-risk infrastructure, a healthy response would be to encourage everyone to learn to take care of their own needs locally. Learn to make rocket stoves w/mass heaters so you can cook and heat your (small) home extremely efficiently from very little wood. Make and fire your own clay cookware. Build your own home from clay, sand, dried grass, and water, w/a thatch roof, or if you want, scavenged metal (I’ve done both) – or whatever design/materials make sense in your bioregion. It’s all fun for the whole family, non-toxic, and free. Plus you get to invite friends to help you, and later you’ll help them in turn, building meaningful bonds and memories.

Study native cultures and local wild plants and animals, and become dependent on the living world instead of industrial society, and you’ll learn how happily you can live locally.

O ye of little faith…..

In the 1890s economic growth and growth of cities had created a massive pollution crisis – horse poo everywhere. by 1912, that problem was largely solved by the internal combustion engine replacing horses: https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Great-Horse-Manure-Crisis-of-1894/

By the 1950s, coal burning and the internal combustion engine had created massive air pollution crises that were literally killing people in the industrialized world. So technologies were developed to address this. Despite the wails of excessive costs, the economy continued to grow successfully.

Electric cars are real and competitive but still lack the charging infrastructure. But there weren’t many gas stations in 1900 either. https://www.businessinsider.com/chevy-bolt-review-best-features-and-charging-challenges-2018-8

Areas with sun will likely be having many more solar power installations, once the solar panel improvements will allow them to be efficiently built into architectural roofing and window systems.

I have a hybrid sedan that looks and feels like a regular car but averages 40-50 mpg in good driving conditions. I have been utterly baffled why more pick-ups and SUVs are not hybrids as gas costs would plunge for the owners. The high torque at low rpm of electric motors also makes them efficient for towing. I think this a cultural thing that could change quickly if we see $100 oil again.

I don’t see any reason why we can’t reduce GHG in the coming decades without impacting growth. I just shudder to think that it will be China that will be the leader in this instead of the US and Europe. That would simply be voluntary abdication of our economic leadership on our point if that occurs.

“I don’t see any reason why we can’t reduce GHG in the coming decades without impacting growth.”

This is the framing of 30 years ago. At this stage, we have to be aiming for net-zero emissions as soon as possible, because we waited so long. You are definitely right that huge strides could be made, but I think there are big questions of corporate power lurking behind all of these things. Automobile and fossil fuel companies *want* ICE cars, and I think Americans have to confront that in a way we don’t seem capable of.

The point of this article is not that we need to all switch to hybrid vehicles. The point is that we need to stop driving. Only dramatic changes in our way of life, our economic system, what we value as “quality of life” will bring about a shift dramatic enough to impact climate change in time. Without a war-footing mobilization, doubling the energy efficiency of our vehicle fleet while nice will just lead to more miles driven, similar to the proliferation of LED lighting resulting in more light rather than reduced energy usage. There isn’t the will for this yet, and I worry there never will be.

Thank you, for an excellent point. Cree, a US firm, who almost single-handedly made LED lighting the miracle of efficiency, benefitting pretty much everybody, aside from their shareholders? New Yorkers whine and bitch non-stop about LED street lighting, other firms steal their intellectual property.

Actually, I believe it’s the color (white) of the emitted LED light that appears to make it appear the street lights are using greater power than the yellow glow of the older sodium vapor lights. I don’t see many municipalities adding new street lights (posts and lamps) and the LED’s in existing light posts use ~70% less energy. (Although LED technology is more expensive; most cities see a less than 7 year payback–and reduced maintenance costs.)

A bunch of the original lights in Riverside Park have either kicked the bucket, prematurely, or at least their sensors have. We’d figured these were just slapped together by child slaves in China and any FLIR/ CMOS cameras had facial recognition & hypercardioid mics translated every utterance, like They Live, or The President’s Analyst?

https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-smart-street-lighting-ny-program-all-municipalities-across-state

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2018-12-06/protest-in-paris-end-of-the-world-versus-end-of-the-month/

https://www.citylab.com/life/2018/12/working-class-service-creative-social-issues-gun-control/577108/?utm_source=feed

Sodium lights are very efficient, but they emit a very narrow bandwidth of light (at 589nm), yellowish orange due to the excitation method used for the sodium vapor. These lights can be 190 lumens/watt which is better than current LEDs on the market (~150 lumens/watt). Color rendering is terrible though. The phosphors used to emit light with LEDs are more efficient the “bluer” they are skewed, which leads to the problems and complaints as we as humans (and other animals too) have evolved to interpret bluish light (sunlight) as a cue to wake up. So the proliferation of high efficiency blue tinted light from LED backlit screens and outdoor lighting has had an impact. Lifetime on LEDs has also not met the hype, with the constant current electronic drive circuits being the main culprit. Cheap capacitors failing in my experience.

Thank you. I’d been using LED lamps for inspection, safety and automotive lighting, due to very specific criteria. So, had a very limited perspective on their downsides in other applications. Acquisition of novel technology by municipalities is always hilarious (I’ve watched a brother introduce automated transit control systems from airports to large city mass transit over the last 40 years and find the thinly veiled kleptocracy amusing). I’m intrigued by by being surrounded by autonomous Fords & Chinese Volvos, electric scooters and mopeds… into my befuddled dotage.

Remember when we all were going to “work from home”? Yeah, me too. Yet wasn’t it Marissa Meyer, CEO of Yahoo (not Chevrolet, not USS, not some Koch Industries sweatshop) of all things the one that insisted everybody come to work?

Honestly I cannot even imagine what anybody actually does “at work” for Yahoo.

We are so (family blog)ed.

Kate Aronoff has an article that discusses your Third sentence at The Intercept:

https://theintercept.com/2018/12/05/climate-change-economics/

Ah, er… https://urbanomnibus.net/2018/06/illuminated-futures/ how’d this get down here?

Why do you think increased fuel efficiency leads to more miles driven? Miles driven has almost flatlined over the past decade since 2008 despite the most fuel efficient fleet ever and relatively low fuel prices. Until 2008, miles driven increased at a steady pace despite wild fluctuations in fuel costs and changing emissions and fuel efficiency standards. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M12MTVUSM227NFWA

In our family, every baby boomer had a car by their early 20s. Now, only half our millennial kids, nieces, and nephews have cars despite being in their 20s and early 30s. This is largely due to increased urbanization with more people living in areas serviced by mass transit and walking.

In our house, nearly all of our lighting was converted to CFLs and now to LEDs. That has not led us to adding new lights or even greatly increasing the lumens of the lights. So our lighting energy consumption has plunged about 80% over the past 20 years. Our appliances have gotten a bit more efficient, but nowhere close to 80%.

I think we can make a major shift economically to a much greener approach in energy generation, transmission, and usage over the next 20 years if we want to without significantly impacting growth. I am actually much more concerned that the impacts to economic growth will come from unplanned consequences of not addressing climate change and sea level rise ahead of the curve. https://www.npr.org/2018/12/04/672285546/retreat-is-not-an-option-as-a-california-beach-town-plans-for-rising-seas

The rebound effect is very well documented.

We are seeing the rebound effect in the increase in sales of trucks and SUVs resulting in the closure of the small car plants announced by GM. However, we are not seeing a significant increase in miles driven which was the rebound effect claim above. The rebound effect is in fuel consumption due to decreased fuel efficiency, not using the vehicles more.

Bigger vehicles using more fuel is purely a financial cost to the consumer. Driving more miles is a time cost as well as a financial cost, so we are seeing this flat-lining as more people forego vehicles.

How much of the money saved by those who replaced their light bulbs, or don’t own a car, is the spent on long-distance vacations and cruises?

There are those of us who do have the will and we need to lead by example. We need to push the boundaries of what we think we can tolerate. People are scared because they are addicted to carbon fuels and a certain level of comfort. But comfort is a conditioned response, nothing more.

I am one person who can do lead by example, and expect more publicity from me in the future.

We’d given up our leadership in this market as descried by Carter four decades ago. Aside from tiny companies struggling with CNG micro-turbine garbage trucks or adapting soil microbes, or AI to optimize all transport; we’ve simply stomped down entrepreneurial innovation and competition in sustainable energy, regenerative agriculture & smart infrastructure (certainly, nothing new?) https://www.demsagainstthe.net/

But you have to remember that the US is manipulating the price of oil to punish Venezuela, Iran, and Russia by lowering their ability to make money by selling their oil.

How much longer this economic warfare can go on is part of the complex issues that determine both how fast we might see the cultural change you seek, and the length of that time period during which is we see continuing damage/climate change.

Yes Watt4Bob, the gamesmanship that seems to be preventing real progress on climate change is disheartening, but maybe rational. I’ve taken to calling it Climate Fight Club.

The article states:

The authors realize that supply side fixes are all voluntary while the demand side are voluntary or “nudged”. This nudging is almost always the Mr. Market stick of taxation that increases costs to consumers. A gas tax is a direct tax on consumers and a carbon tax is a tax on corporations that would inevitably be passed on to customers so as to keep profit margins high. This is not a popular solution as can be seen by the “Yellow Vest” protests.

This scenario must be reversed. The supply side must be “nudged”. We can determine what corporations are producing CO2 for a carbon tax. Instead of taxing those corporations directly have a very progressive tax on the income derived from dividends and capital gains of those corporations. The proceeds from this tax would be used for a Mr. Market carrot “nudge” for consumers. Such as subsides for low cost efficient personal transportation which actually could decrease costs for consumers.

Drying up investment for polluting industries would hopefully drive investment into “green growth” industries for better after tax returns. Lower costs for consumers would give this scenario popular support.

Anyway, taxing the elites always makes me much happier.

we just voted for a gas tax here in Cali and it passed by a very strong lead and we already pay more for gas than anywhere else in the U.S., so it actually IS a popular solution as seen by those ballot results.

Of course it wasn’t perceived as punitive or even to save the world, but to fund transportation. So people definitely thought they were getting something for it. But if taxes were shifted to punish environmentally damaging practices we could have something for it.

Taxing the shareholders is a decent plan. Personally I’m sympathetic to nationalizing all energy production, so the future of the world at least wasn’t in the hands of a few for-profit corporations but ..

Does the new gas tax lead to gasoline prices approaching the higher levels in worldwide prices? See https://www.globalpetrolprices.com/gasoline_prices/

It will be whatever human action are or are not taken.

You are so right, Synoia. Radical change is coming, whatever we do.

But, we can decide whether we want that change to result in a miserable, short and brutish life for the majority of people on the planet, while a comparatively few wealthy (or lucky) people ride it out, or if we want the change to be eased in so that as many people (and other species) suffer as little as possible. And, this is important, we want the suffering to be shared. As well as the joys.

We might want to regard the various reactions to the news of climate change like Kubler-Ross’ five stages. We have received notification of the impending death of Earth. Which is a foretelling of our individual deaths, and those of our children and grandchildren, as well.

First there is Denial …. and that’s been going on for five decades, at least. Then, Anger, which means we yell at each other, since Earth does not argue. Or, maybe we take our our Anger by drilling, blasting, fracking and de-forestation.

Of course, mixed with all this is Depression, which all of us experience, at least for a few minutes each day, when we contemplate the death of our Home.

Many of us have now moved to the Bargaining stage; we will promise to go 100% ‘renewable’ energy or nuclear energy, but let us keep our SUV’s, 3,000 square foot centrally-heated and air-conditioned houses, flights to tropical islands for mid-winter vacations, strawberries in January and skiing on man-made snow. And as many children as god gives us.

Finally, there is Acceptance. Which is hard. Earth is dying because we humans, with our fossil-fuel addiction, are killing her. And with her, die all our blameless relations; bees and other pollinators, predator wolves and mountain lions, eagles and elephants, migrating salmon and pods of whales.

We know which of our actions are killing Earth. So, we must stop doing them. Now. And, it is up to those of us who have reached the Acceptance stage, even if it’s only for a few minutes a day, to start manufacturing consent. Because this is undoubtedly the most important thing most of us will ever do.

Gerard Manly Hopkins wrote a poem about the dawning realization of death, which begins:

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Its final line: “It is Margaret you mourn for,” could describe our realization that while we consciously fear the loss of our ‘life-style,’ our deeper mourning is due to the knowledge that our own deaths and those of our loved ones are inextricable linked to the death of Earth.

I agree. Great changes are coming no matter what we do. Few want to believe that and fewer still willingly look into the future to see the dark changes that are coming. Our way of life is not sustainable. We can accept that fact and work to adapt or we can reject that fact by various acts of self-deception and face the far more dire changes of a great ‘Jackpot’. Green economic growth is an especially pernicious form of self-deception sold by our Neoliberal overlords — just one of many ways they might profit from TINA and the speeding drive toward the Jackpot.

I’m beginning to think that one easy way to make progress is for the US government to give away electric cars, and drop the price of electricity. Other drastic changes also must be done: M4A, free college, etc. Biggest goal is to break the current economic neolib model, and move towards a minimal CO2 life.

How do we “afford” it? Just “go to war” against global warming or “bail out” the people. After all, the last war was against a word, “terrorism”, and bailing out the banks was perhaps the worst “solution” to the disaster of 2008. How did we afford all that? Who cares.

The repeated assertion that the general public has no appetite for making changes that would help is, I think, based on facts not in evidence (as the saying goes), but nothing will change so long as there is no urgency. Pointing at the obvious and in-your-face hypocrisy of our “elites” in the way they waste energy may be a logical break chastised on this site, but until we all see people like Al Gore taking steps to reduce their own emissions, movie stars not standing on stages lecturing us about global warming after they jetted around the planet to get to the stage, Barack Obama not demanding that we thank him for an increase in carbon fuel production, Macron not insisting the mopes pay more for diesel while he continues to squander resources, we won’t feel that urgency.

And in an aside, can’t authors mange to go for an entire article without some snark directed at Trump? I realize that’s not the fault of NC, but doesn’t the author realize that snide attempts to be cool does not help his cause (especially when he then cites Obama at great length, right after Obama bragged about increasing fuel production)? He reminds me of the people who criticized conservation efforts in Kansas because the efforts were sold as part of a Christian’s duty to care for the planet. The NY Times was full of people ridiculing effective conservation efforts because those hick Kansans weren’t doing it for the RIGHT reasons. *sigh*

Good points, all. I don’t think regular folks are opposed to changes in their lifestyle to effect reduction in GHG’s. It’s that the changes need to be rapid and the path is unknown (at least obscure).

Regular folks are looking for “fairness” as we travel that path to a low carbon future. (I think that is the point of the Yellow Vests in Paris.) And that points to the issue being Political as much as technological.

Did you read the article? Obama is not “cited” at length, he is criticized. The article is basically written around debunking Obama’s belief–which is very commonplace among other neoliberal centrists–that green growth is possible.

And Trump has been the worst president we’ve had regarding climate change and environmental policy. I couldn’t have imagined that we could get any worse than Bush but what we’re seeing right now is a whole new level. So I don’t mind a bit of snark.

One more thing…first, could you please post a link to the NYT article?

Second, while some people are willing to pay small price premiums on more sustainable products, and a small minority of people actually take some steps in their personal lives to reduce their carbon footprints, the entire population would need to vote in leaders asking us to make huge sacrifices. Giving up flying, driving, red meat, most consumer goods, our current system of housing…do you think any leaders calling for those things will get elected? And then of course there’s the dreaded “jobs” argument (that the resulting drop in GDP from these environmental policies will take away their jobs). Americans just aren’t going to do that. This is a land of plenty, and God didn’t mention climate change in the Bible, so saying otherwise is just un-American.

God didn’t mention climate change? Noah’s Flood? Though that was not permanent enough, apparently.

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/19/science/earth/19fossil.html

Read the comments. NT Times readers were more concerned that people parrot the approved language about climate change than that they actually *do* anything about it.

Interesting discussion on French media site (sub-titled in English) about this topic and the idea of Collapsology:

https://www.arretsurimages.net/emissions/arret-sur-images/effondrement-un-processus-deja-en-marche

(scroll to the bottom of the page just above ‘ÉMISSION SOUS-TITRÉE EN ANGLAIS’

Thank you for this link. Finally, understanding the French language comes in handy!

“Collapsology” has become valid as a field of inter-disciplinary study. Since climate change is an inevitable consequence of the unprecedented explosion of human population (7.7 Billion and growing), how do we prepare for a humane and orderly collapse of industrial civilization? Is this even possible?

Sadly, I am a pessimist about climate change, but the panelists on Arrêt sur Images appear to be pretty thoughtful about the topic.

for me, new words in this discussion: Collapsology, Anthropocene, de-growth…

“we know, with Ludwig von Wittgenstein, that nothing is so difficult as not deceiving oneself. Hence, if past performance is relevant for future outcomes, our results should put to bed the complacency concerning the possibility of “green growth.” There is no decoupling of growth and consumption-based CO2 emissions – “green growth” is a chimera.” This says it all. Dieoff.org gives a lot more. One article in Resilience.org proposed a flip on the tithe…give 90 keep 10 %. Dover Press has an old reprint “5 Acres and Independence”.

“Without a concerted (global) policy shift to deep de-carbonization (Sachs 2016; Fankhauser and Jotzo 2017), a rapid transition to renewable energy sources (Peters et al. 2017), structural change in production, consumption and transportation (Steffen et al. 2018), and a transformation of finance (Mazzucato and Semieniuk 2018), the decoupling will not even come close to what is needed (e.g. Storm 2017).”

I agree completely with everything the article said (thank you for sharing this Yves; it was a great post), but they left out the most obvious solution of all: reducing red meat consumption.

The reality is that as long as we continue to make strides in renewable energy and clean transportation, all we would need to do is eat beans instead of beef and we would beat climate change.

I wonder what our descendants will think of us as we enter a post-apocalyptic world due to a ruined planet–we would have survived as a species only if our great-grandparents had changed their diets. Maybe they’ll start killing all the old people first in anger.

That claim has been addressed several times on this site just within the past few months. It is false and appears to be based more on political correctness than science. In fact, properly managed grazing helps mitigate damage to the environment. Not to mention, there are areas which are NOT suited for crop production but have a grazing carrying capacity.

Could you link to where the claim was addressed? The only thing I have found was this

l which seems supportive of the claim.

well how on earth would one know if the grazing was properly managed? I can’t imagine what percentage of beef in the U.S. might meet the criteria .00001% maybe? (and that’s beef raised in the U.S., given beef is being imported from the Brazil and the like at the cost of the rain forest as well …).

I don’t think grass fed is enough, it’s an improvement in some ways (use of antibiotics probably, grass is the natural diet for a cow), and yes I do like the taste (not actually a vegan here but willing to give up some things), but it’s not an improvement in terms of GHG as far as I understand it.

If the claim is “beef is incredibly damaging to the environment, until we radically change the entire animal grazing system”. Well ok, maybe. But I have seen good sources on the impact of beef (and lamb) on the environment and it seems to be the worst food (dairy is second but not close).

GHG and food:

https://www.wri.org/resources/data-visualizations/protein-scorecard

Lynne–

This is news to me. I read NC pretty regularly and did not see anything on it. Please link.

I’ve read in too many places that the GHG emissions for red meat consumption are extremely high for me to believe that it is a false claim. See this Guardian article, for example. Or the IPCC report that claims that 24% of global GHG emissions are from agriculture.

Or you have the TEEB study that found that the second largest impact on natural capital by sector-category was cattle farming in South America for land use (coal power generation in East Asia for GHG emissions was first). Granted, that doesn’t have to do with GHG emissions, but under the GHG emissions category, South American cattle farming was ninth on the list and cattle farming in Southern Asia was 16th.

You are right about properly managed grazing but the problem is that it is not scalable because it doesn’t work in most regions. This is the only link I could find off the top of my head but it is impossible for us to have managed grazing on the scale required to feed current American red meat consumption habits (the average American eats almost three times as much meat as the average Japanese person, for example). Sure there is a future for red meat, but the only way to do it sustainably is with small numbers of cows grazing on huge managed pastures with the beef later selling at extremely high prices.

Please tell me how I’m wrong so that I can feel less guilty about the red meat that I do consume on occasion.

You could try a search on holistic range management, or search for soil health and NRCS. ASU has done studies on it. Others have posted links on NC in the past to work that is being done. The Sierra Club article you cite is relying on old science and practices that have been discredited for decades.

The IPCC report on agriculture includes fertilizer, land clearing for cultivation, etc, all of which are reversed by modern good grazing practices. They would, however, all be called for if we all switched to pulses for all our protein.

Try this excellent report: Grazed and Confused

Ruminating on cattle, grazing systems, methane, nitrous oxide, the soil carbon sequestration question – and what it all means for greenhouse gas emissions. https://www.fcrn.org.uk/projects/grazed-and-confused

It’s lengthy and quite thorough. Upshot: There are many types of grazing systems referenced (and I haven’t had time yet to sift through the methodologies of all of the source papers), but it’s not a good look for most ruminants in most grazing systems due to methane production. Soil carbon sequestration as a benefit of good management has limited benefit, as it hits a ceiling after a period of time. As a farmer, I think that extensive (i.e. very low density) grazing systems on land not suited for crops would be the best possible scenario, but that certainly does not provide everyone in an increasingly populated world a burger for supper. The key term here is “increasingly populated”.

We’re not that far apart. What I object to is the idea that if only we stopped eating meat completely and only ate beans, we’d be fine. There are some areas that should have never been plowed and the best use is grazing. To continue or expand cultivation would be a disaster, and all because the popular press pushes that it’s virtuous not to eat meat.

Beans instead of beef? Wouldn’t that just change the source for the methane?

No.

If the red meat being avoided is corn-soy feedlot meat, then avoiding it will avoid some carbon releases.

But if the red meat being avoided is carbon-capture meat on pasture and range, avoiding it simply prevents that biological carbon capture. Whereas BUYING and EATING the pasture-and-range carbon-capture meat would incentivise the carbon-capture farmer to grow more pasture-and-range meat animals, which would keep the farmer in bussiness even longer capturing even more carbon.

So it depends on WHICH meat is being avoided.

While not a solution in the short term, there must be negative population growth to make any global warming mitigation sustainable. Humans have avoided the Malthusian end-game by increasing expenditures of energy going to resource extraction and throughput. This is having the impact of crippling the substantial environmental services of intact ecologies. We may already exceed the carrying capacity of a rapidly warming world.

Population control remains a taboo subject with respect to global warming even as growth is the logic of a cancer cell.

The answer I think lies in technological breakthroughs coming in the not so distant future.

There is enough energy coming in from the sun every two hours to power all humankind’s activity for one year. https://gulfnews.com/uae/environment/two-minutes-of-sun-enough-to-power-a-years-usage-of-humanity-1.1910990

Right now, our solar electric efficiency is below rudimentary. It’s like we are killing whales to keep the lights on in Philadelphia. But in 40-50 years, things should change. Cheap, abundant, clean energy from the sun. That is the future.

Problem is we don’t have 40-50 years.

I’m wondering what all the leaders are doing that they aren’t leading, specifically corporate leaders. I guess peer pressure doesn’t work on oil and gas executives ?? Obviously CAFE standards made a huge impact for cars, and new standards can do it again. Solar, wind, nuclear… there’s no reason that the climate change issue can’t be resolved. I’m sure I will have a solar car within the next 10 years. I can’t wait to see the Saudi’s loose the income from oil and all the power that goes with it, including their abuse of women.

My prediction:

Soon the media, which has been all but stum on the subject, will start talking about climate change as if it was always an inevitability. The reports will be upbeat and focus on “climate resilience.” A feature about a nondescript small town that is making itself more attractive as residents and businesses work to “build in” resilience to climate change, or a nice story about a family that “added value” to their home by making it climate resilient, and how you too can upgrade your home!

It will be all about downplaying the seriousness of a warning planet while telling people how to “deal with it” on a personal and local level. The causes behind the climate going out of whack, and large scale efforts that could be undertaken to mitigate the most serious effects, will get next to no coverage and be characterized as “unrealistic.”

The poor countries of the global south will likewise be praised for showing “climate resilience” and the looting of resources and IMF/World Bank usury will continue apace. Meanwhile various power blocs with the ability to do so will be working behind the scenes to keep the desperate southern masses from coming anywhere near their borders. The German military, under EU auspices, is already collaborating with corrupt government officials and warlords in Mali to keep people from heading North toward the Mediterranean, effectively building the first layer of the EU border in the middle of the West African desert.

If thousands of refugees and migrants drowning in the Med, thanks to EU policies, doesn’t disturb the Eurofolk, neither will would-be migrants “getting lost” in the desert a few thousand miles from Europe.

In short, nothing significant will be done at the international level to mitigate the effects of climate change. The powers that be will try to keep their corrupt trough network stocked and flowing for as long as possible while using the media to pacify the citizenry and the military to keep the starving and desperate hordes at bay. When the family blog really hits the fan, they will (try to) abscond to their bespoke bunkers in New Zealand while the rest of us will be left to double down on the “climate resilience.”

What is growth? We usually measure it in terms of GDP, but that is a measure that has been widely criticized. At best, GDP is an approximation, at worst it is just an artifact of the manipulations of the ruling class. The things people try to do to save money are often the very kinds of things that will create a better world, even as they risk lowering the GDP. We do not need more single-use throw-away plastic. My wife and I have been saving money by still using the same stainless steel flatware we got when we married, and the same tough dishes my wife had before we got married. We do not add to the GDP when we use the same old stuff year after year, but we still live well. Reducing planned obsolescence could do a lot to improve the world even as it probably would reduce GDP.

On a larger scale, stopping and preventing needless wars will lower GDP, but make the world a better place. Also, I suspect, considerably reduce carbon emissions. Universal education, comprehensive sex education, and easy access to birth control and abortion have been shown to stop population growth. Again, probably lower GDP will follow, but also a better life. Do it once, do it right, keep it simple.

The same neo-liberal inequality that is causing social unrest around the world is also driving global warming. We need a green sustainable economy, with enough inequality to keep the system dynamic, but enough equality to keep the peace, and to allow us to focus on more than simple survival. If we can do this much, we might reach the point where we are ready to tackle more deeply reinventing our economy and our society, as the challenge of global warming demands. There is no silver bullet, but if we find the hope and courage to step up to the challenge, we might grow the understanding of how find our way. There is no way that exponential growth can continue indefinitely on a finite planet. Only our creativity can grow like that.

There’s also an article about this and its companion article on The Intercept today: https://theintercept.com/2018/12/05/climate-change-economics/ . Might be a useful quick introduction.

I just recommended it, but Yves beat me to it with this.

WW1 was a harbinger of change in both money and growing food…

Heretofore, we were limited on both fronts from expanding and the population reflected it, but enter the Bosch-Haber process, and fiat money, and suddenly the sky’s the limit~

…I suspect both will collapse somewhat in tandem

Absolutely superb article in today’s CounterPunch about this very subject, perhaps the best I’ve encountered in quite some time. Please give it a shot.

https://www.counterpunch.org/2018/12/07/degrowth-toward-a-green-revolution/