By Lambert Strether of Corrente

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) originated with a 2007 report to Congress from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the agency within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that administers Medicare and works with the states to administer Medicaid, among other things including ObamaCare. From that report, “Promoting Greater Efficiency in Medicare” (PDF), page 8:

The concept of efficiency should include not only getting more for a set amount of inputs, but getting more of the right care. … Another aspect of efficiency is getting the right amount of care over an entire episode of care. One possibility we discuss in this report is to decrease the number of avoidable hospital readmissions through higher quality care, better care transition at discharge, and better care coordination.

And from page 16:

To encourage hospitals to adopt strategies to reduce readmissions, Chapter 5 explores a two-step policy option that starts with public reporting of hospital-specific readmission rates for a subset of conditions. The second step of the policy is an adjustment to the underlying payment method to financially encourage lower readmission rates. For example, one could create a penalty for hospitals with high readmission rates and hold all other hospitals harmless.

In 2012, ObamaCare implemented this policy option. From CMS:

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) is a Medicare value-based purchasing program that reduces payments to hospitals with excess readmissions. The program supports the national goal of improving healthcare for Americans by linking payment to the quality of hospital care.

Section 3025 of the Affordable Care Act requires the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish HRRP and reduce payments to Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) hospitals for excess readmissions beginning October 1, 2012. CMS uses excess readmission ratios (ERR) to measure performance for each of the six conditions/procedures in the program:

- Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI)

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

- Heart Failure (HF)

- Pneumonia

- Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Surgery

(Spoiler: CMS doesn’t measure performance; it measures reported performance.) Or in something closer to English, from Colleen K. McIlvennan, Zubin J. Eapen, and Larry A. Allen, “Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program,” Circulation. 2015 May 19:

Hospital readmission measures have been touted not only as a quality measure, but also as a means to bend the healthcare cost curve. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) established the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP) in 2012. Under this program, hospitals are financially penalized if they have higher than expected risk-standardized 30-day readmission rates for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia. The HRRP has garnered significant attention from the medical community, both positive and negative

Now, stepping back and putting on my layperson’s hat here, I don’t think anybody wants to go to the hospital, at least for illness, and nobody wants to go back to the hospital, either (which is sensible: superbugs). So on that level, minimizing re-admissions makes a lot of sense. On the other hand, I don’t want to be prematurely discharged, and if I really need to be, I do want to be admitted. Both are aspects of the same thing: I want the hospital to decrease my risk of mortality. As it happens, we’ve had two major studies in HRRP released recently, both bearing on HRRP. The first, from JAMA, focuses on mortality. The second, from Health Affairs, shows that hospitals gamed the medical coding system to make their HRRP numbers seem better than they really are. The results of the first are… not the greatest, but health care policy really is hard; absent proof of malfeasance or some malevolent form of cognitive capture (***cough*** neoliberalism ***cough***), I’m inclined to give a free pass. The second, however, is horrifying. If hospital re-admission data is gamed, how deep does the gaming go?

The JAMA Study on HRRP Mortality

The JAMA study (“Rohan Khera, Kumar Dharmarajan, Yongfei Wang, et al., Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program With Mortality During and After Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction, Heart Failure, and Pneumonia“, JAMA Netw Open. 2018) was quite large. From the abstract:

Findings In this retrospective cohort study that included approximately 8 million Medicare beneficiary fee-for-service hospitalizations from 2005 to 2015, implementation of the HRRP was associated with a significant increase in trends in 30-day postdischarge mortality among beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure and pneumonia, but not for acute myocardial infarction.

Meaning There was a statistically significant association with implementation of the HRRP and increased post-discharge mortality for patients hospitalized for heart failure and pneumonia, but whether this finding is a result of the policy requires further research.

It’s worth noting that the full text seems more sanguine:

Question Was the announcement or implementation of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) associated with an increase in mortality following hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia among Medicare beneficiaries?

Findings In this cohort study, between 2006 and 2014, in-hospital mortality decreased for the 3 conditions while 30-day postdischarge mortality decreased for acute myocardial infarction but increased for heart failure and pneumonia. Before the announcement of the HRRP, postdischarge mortality was stable for acute myocardial infarction and increasing for heart failure and pneumonia, and there were no inflections in slope around the announcement or implementation of the HRRP.

Meaning There was no evidence for increase in in-hospital or postdischarge mortality associated with the HRRP announcement or implementation—a period with substantial reductions in readmissions.

And from the conclusion of the full text:

Among fee-for-service elderly Medicare beneficiaries, there was no evidence for an increase in in-hospital or postdischarge mortality associated with either the HRRP announcement or implementation—a period with substantial reductions in readmissions. The improvement in readmission was therefore not associated with any increase in in-hospital or 30-day postdischarge mortality.

Again, putting on my layperson’s hat, I can’t tell whether the JAMA study says that HRRP increased mortality or not (or whether I should choose to come down with pneumonia or have a heart attack). Other authorities, including JAMA editors, say it does. From the Cardiovascular Research Institute:

The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP), enacted by the 2010 Affordable Care Act, appears to have led to an increase in deaths within 30 days of discharge in Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure or pneumonia, leading researchers to conclude that more investigation is needed into the possibility that the program has had unintended negative consequences.

However, there was no such pattern seen in patients who had been hospitalized for acute MI.

“Though postdischarge deaths for patients with heart failure were increasing in the years prior to the HRRP, this trend accelerated after the program was established,” said Rishi K. Wadhera, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), first author of the new report. “In addition, death rates following a pneumonia hospitalization were stable before the HRRP, but increased after the program began.”

The study, published online today in JAMA, shows that the increase in deaths among heart failure and pneumonia patients was concentrated in those who had not been readmitted to the hospital. “This raises the possibility that the HRRP may have pushed some clinicians and hospitals to increasingly treat patients in emergency rooms and observation units, when they would have benefited from inpatient care, to avoid readmissions,” Wadhera added.

In an accompanying editorial, Gregg C. Fonarow, MD (Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), says the new study together with other recent analyses provides “independently corroborated evidence that the HRRP was associated with increased postdischarge mortality among patients with heart failure, and new evidence that the HRRP was associated with increased mortality among patients hospitalized for pneumonia.”

Fonarow urges that, in light of the findings, “it is incumbent upon Congress and [the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)] to initiate an expeditious reconsideration and revision of this policy.”

In an email response, senior study author Robert W. Yeh, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center), said caution should be exercised before undertaking further expansion of the penalties to more health conditions.

“But unfortunately, causality is really very difficult to establish with this type of analysis,” he added. “So, I want to be equally cautious in not overstating the strength of our evidence that the HRRP has definitively harmed patients. The HRRP has clearly been successful at reducing readmission, something which patients care about. Right now, I think we still don’t have a complete answer, and more work still needs to be done.

Infinite are the arguments of mages. More study needed! And, to be fair, causality is genuinely difficult to establish. And now let me turn to medical coding, which is a great deal simpler.

The Health Affairs Study on Medical Coding

And now to the second study: Christopher Ody, Lucy Msall, Leemore S. Dafny, David C. Grabowski, and David M. Cutler, “Decreases In Readmissions Credited To Medicare’s Program To Reduce Hospital Readmissions Have Been Overstated“, HEALTH AFFAIRS, VOL. 38, NO. 1. I had intended to be able to quote from the full text, but sadly only the abstract is available to me. Here it is:

Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) has been credited with lowering risk-adjusted readmission rates for targeted conditions at general acute care hospitals. However, these reductions appear to be illusory or overstated. This is because a concurrent change in electronic transaction standards allowed hospitals to document a larger number of diagnoses per claim, which had the effect of reducing risk-adjusted patient readmission rates. Prior studies of the HRRP relied upon control groups’ having lower baseline readmission rates, which could falsely create the appearance that readmission rates are changing more in the treatment than in the control group. Accounting for the revised standards reduced the decline in risk-adjusted readmission rates for targeted conditions by 48 percent. After further adjusting for differences in pre-HRRP readmission rates across samples, we found that declines for targeted conditions at general acute care hospitals were statistically indistinguishable from declines in two control samples. Either the HRRP had no effect on readmissions, or it led to a systemwide reduction in readmissions that was roughly half as large as prior estimates have suggested.

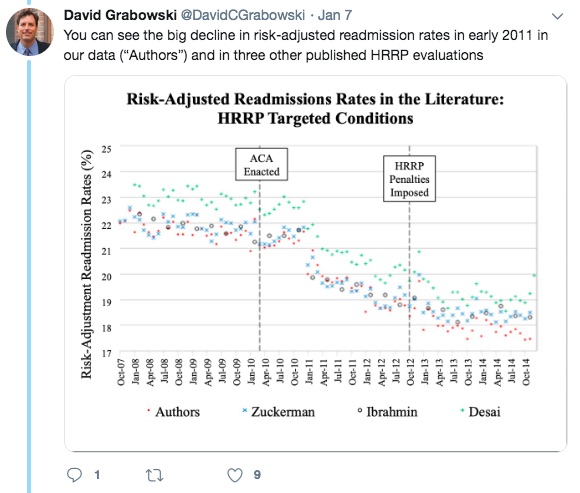

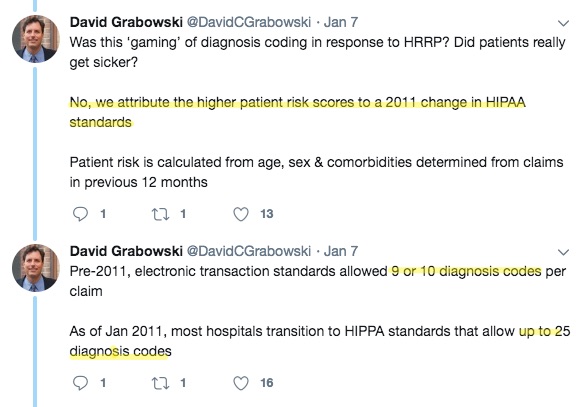

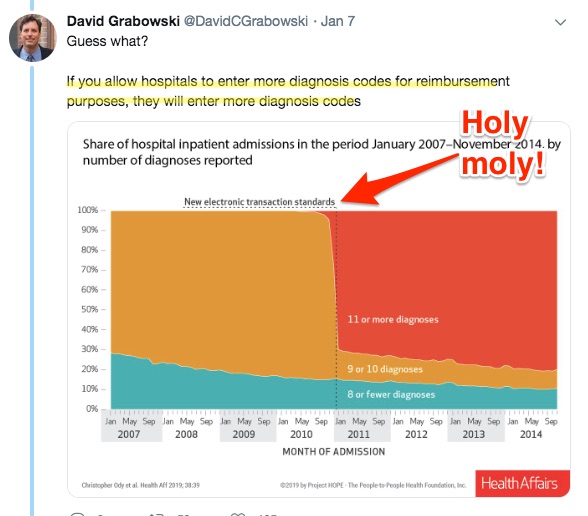

Did the hospitals game the medical coding? Not at the code level (e.g., through upcoding). From a tweetstorm by author Grabowski, first we see the reduction in re-admissions:

Were the hospitals gaming the codes? No:

They were adding more codes![1]

Which makes sense from the standpoint of you as an institutional provider; if your profit (or whatever non-profit hospitals call profit) is dependent on Medicare reimbursements, and your profit is also your ability to accumulate and allocate capital, then by all means code, code, code!

However, now your coding is driven, as Grabowski et al. point out, by business and not medical necessity. Let’s return to the JAMA article:

Data SourcesWe used the Medicare standard analysis data files (2006 to 2014) and defined AMI, HF, and pneumonia hospitalizations as any hospitalization with a primary discharge diagnosis of the respective conditions, as in prior studies. We also obtained information on patient characteristics including demographics (age and sex) and mortality using the denominator files, and relevant comorbid conditions from the diagnosis codes in the insurance claims submitted to Medicare across inpatient and outpatient care settings.

And from the discussion section:

A notable finding is that postdischarge mortality among patients with pneumonia and HF has been rising since 2007. Prior studies and publicly available data suggest a similar trend. For [Heart Failure (HF)], this represents a change from improvements observed in prior decades. There are no clear explanations for this change. For both HF and pneumonia, we found an increase in the coded severity of illness as well as a decrease in the number of hospitalizations. Therefore, the increasing complexity of patients may manifest with an increase in early postdischarge mortality, particularly because risk adjustment may not adequately account for all changes in illness severity over time. Further, the decreasing in-hospital mortality despite such an increase in coded severity argues that there may be alternative factors driving this trend in postdischarge mortality. Notably, there has been a concomitant decrease in in-hospital mortality for both conditions, and accounting for this decrease in the assessment of hospitalization-related mortality attenuates the increased mortality observed in the postdischarge setting. This also suggest that while fewer patients died during hospitalization over time, the actual improvement in patient outcomes may be less substantial.

But if the coding is driven by the bottom line, instead of health care…. We don’t really know anything, do we? Further study is warranted, but of what? How does one practice scientific medicine under neoliberalism?

NOTES

[1] CMS on HIPAA codes; there are many. I don’t think the technical characteristics or topics for any code set can possibly determine the uses to which they are put for business purposes.

Was the shift from ICD-9 to ICD-10 a factor? There are a lot more ICD-10 codes than ICD-9 codes.

It may have had some impact, DV, but as is so often the case, it’s wise to follow the money. Coders don’t code for fun (although many of them enjoy their work). The reason that they add codes to a patient’s record is to increase the level of reimbursement to the hospital for the admission. They generally use specialised software (such as that from 3M) to maximise revenue. The software may suggest additional or alternatives codes that can be used, and even the order in which the codes are entered can make a difference. The addition of codes continues until there’s nothing else to code, or the billable total maxes out.

> The addition of codes continues until there’s nothing else to code, or the billable total maxes out.

“or the billable total maxes out.” Oh.

Can you give more detail on the software? Like the name? Is there, perchance, a manual? If it’s not online, my email is over at Water Cooler….

Lambert, you could start with

https://www.3m.com/3M/en_US/company-us/all-3m-products/~/3M-Coding-and-Reimbursement-System-Plus/?N=5002385+3290603315&rt=rud

No surprise there – another self-licking ice-cream.

Clinical coding with ICD codes has always been driven by business needs rather than medical necessity. ICD codes are used to determine Diagnosis Related Groups (DRGs), which are a tool for funding and billing. That’s why a hospital’s clinical coders often report to the finance manager.

Widespread use of medical coding systems (such as SNOMED) has been a separate, and more recent development, driven in part by the desire to use structured clinical data, rather than free text, in patient EHRs.

Should add that much of the US’s hospital billing is not DRG driven.

> That’s why a hospital’s clinical coders often report to the finance manager.

Thanks very much again for the detail. In a past life, I worked on taxonomies/indexes etc., so it’s natural for me to think of these data structures as representing, well, the body, as opposed to profitable operations to extract money through the body.

Same as always – collect reliable data about the problem you wish to investigate. And always be extremely cautious about using data for any purpose other than that for which it was collected in the first place

> Same as always – collect reliable data about the problem you wish to investigate. And always be extremely cautious about using data for any purpose other than that for which it was collected in the first place

A taxonomy is declarative; it cannot enforce the use that is made of it. I don’t see any way that all coding can’t be gamed; it’s a phishing equilibrium (“if there can be fraud, there already is”). How do you clean the data? How do you even know where to begin?

I guess the core issue is that coding for billing and reimbursement is slanted in a way that focuses on billable events, while coding for clinical/medical/patient centred research will have a different focus, ideally with some degree of objectivity (relative to the goals of the research).

Unfortunately it appears there are no systems in place at the point of care for collecting anything other than the data needed to maximize bills.

albrt, there are a many EHR/EMR systems used at the point of care to record and share details of the care provided. These systems replace older system of structured paper records, and are necessary to discharge a medico-legal obligation to document every stage of the patient’s treatment.

The majority of doctors, nurses and other clinicians involved in patient care are driven by an underlying desire to provide the best care they can for the person in front of them. They use EHRs and EMRs to document that care; sometimes the system gets in the way, sometimes it helps.

The process of translating the care provided into a series of billable items (or an overall billable episode) is a separate administrative process which happens after the event. This step usually involves coders, who are not clinicians. The clinicians providing the patient’s care are not involved in the coding and billing process (although they’re probably aware of it to some extent).

This is false. We’ve been posting the work of experts on this topic for years. Agnotology is against our written site Policies.

EHRs were not designed for medical care. They were designed for billing. They were not and were never driven by doctors. Doctors complain that they undermine care by forcing them to devote huge amounts of time to check the box dropdowns that lead them to think less rather than more about patient care.

EHRs were listed in 2014 as a top risk in hospital care:

See more posts:

How Electronic Health Records Degrade Care and Endanger Patients

Criminal Matter for the Attorney General of NY? NYC’s $764M Medical Records System Will Lead to ‘Patient Death’: Insiders

Electronic Health Record Vendors Use Gag Clauses to Hide Lethal Bugs in the IT Systems They Sell

The Ugly Truth About Electronic Health Records

Health Care Information Technology: A Danger to Physicians and to Your Health

And some we missed cross posting from Health Care Renewal:

Medical Economics: Highly experienced physicians lost to medicine over bad health IT

Cambridge University Hospitals Trust IT Failures: An Open Letter to Queen Elizabeth II on Repeated EHR Failures, Even After £12.7bn Wasted in Failed NHS National IT Programme

There are even more. And the author is an IT expert, so don’t even try depicting him as not knowing what he is taking about.

Hmmm. Not sure I can take your rebuke at face value, Yves.

In my post I make a number of points:

o EHR/EMR systems are used to document care.

o They replace paper systems

o Doctors, nurses and others want to provide quality care

o They record care details in EHRs/EMRs

o The quality of those systems is variable

o Extracting billing data is a subsequent administrative process

When you say “This is false”, which of those points do you believe is incorrect?

I agree that many EHR implementations, particularly in the US, are financially driven. Indeed, the majority of the examples in your links appear to be from the US. Even Scott’s open letter to EIIR about Oxford University Hospital describes an implementation of Epic (a US system). (And let’s agree that the NHS’s National Programme for IT was a bit of a dog’s breakfast.)

I also agree that poorly designed systems and poorly managed implementations can leave clinicians frustrated, and thwart their desire to provide high quality care for their patients. Scott Silverstein does an excellent job in identifying those failures, and holding them up for scrutiny.

However, I’m not convinced there are no examples anywhere of effective EHR/EMR implementations with better outcomes. Even VA’s soon to disappear VISTA system has/had its fans among doctors and patients.

You wrote a weasel-worded comment meant to give the impression that doctors were the drivers of EHRs, when that’s false, and made the claim that they were “necessary” which is also false, specifically that they were ” are necessary to discharge a medico-legal obligation to document every stage of the patient’s treatment.” That is absolutely false. Paper records have long done that successfully and they continue to be in use in quite a few medical practices. And I didn’t cite academic articles that have found that EHRs do not save costs, when that was one of the big arguments for their implementation.

Your statement that billing takes place after care is a given, clearly can’t happen any other way unless the doctor/practice is engaged in fraud. In context is meant to give the impression that the EHRs are about care, when they were designed with billing in mind. As for Vista, a simple Google search shows that the DoD has spent $10 billion trying to modernize it and has failed.

You then get passive aggressive and straw man me. Charming. And you haven’t provided a single link and appear not to have read any of the links I submitted.

Well, as someone who fits into the CABG category identified in the study. And who experienced first-hand the ability of doctors and nurses to ignore reasonable complaints of unusual/unnecessary post-op pain, while also attempting to clear me from ICU to Cardio care (via wheelchair) within 12 hours. I am not surprised at the study findings. Hospitals are dangerous places; only SOME of the people working there are competent.

As I’ve commented before: if you go to the hospital, bring your personal physician with you.

Indeed. As Groucho Marx reputedly said:

“A hospital is no place to be if you’re sick.”

Bookmarked for later.

There’s this:

“News Releases

Federal policy to reduce re-hospitalizations is linked to increased mortality rates

Analysis of heart failure data finds a decline in readmissions, but a rise in deaths

11/12/2017

Federal policymakers five years ago introduced the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program to spur hospitals to reduce Medicare readmission rates by penalizing them if they didn’t. A new analysis led by researchers at UCLA and Harvard University, however, finds that the program may be so focused on keeping some patients out of the hospital that related death rates are increasing….

….The analysis of clinically collected data confirms what an analysis of billing data had previously suggested — that the major federal policy, implemented under the Affordable Care Act, is associated with an increase in deaths of patients with heart failure…..

….Therefore, this policy of reducing readmissions is aimed at reducing utilization for hospitals rather than having a direct focus on improving quality of patient care and outcomes.””

https://www.uclahealth.org/federal-policy-to-reduce-rehospitalizations-is-linked-to-increased-mortality-rates

Don’t forget, the same readmission penalties were responsible for the practice of hospitals placing medicare patients in hospital beds, but CODING them as not admitted and tossing them out in 72 hours, exposing them to huge uncovered medical costs while they were in medical distress, simply to game the numbers.

Just as in social service and education, the institutions serving the poor will fare worse in evaluations than those serving the wealthy, punishing them for having sicker patients, even with improvement being incorporated in the measures-type lip service.

There is much similar in meeting health “care” goal measures, or police stats, student tests, or social services generally. With computers now, everything.

Give ’em a ‘target” not qualitatively different than a dartboard and they will hit targets, creaming, gaming, reclassifying, de-classifying, denial of service and so on. What did NYPD do when told to slash felony crime reports? Why, reclassify felonies as misdemeanors, and refuse to take robbery and rape complaints, tossing confused victims out of the precinct. This is the record.

About 2011-2012, local mandarins around the country convened meetings to divvy up the ACA pie; in cook county with government agencies, big 5 insurers and the requisite policy “experts” trotted in from U of C babbling about bending cost curves and data-driven measures.

Any idiot could predict the result, including me so I did, right in the middle of the catered circle-jerk. During this honeymoon period, they were deaf to any dissent no matter how obvious. They still are because they’re paid to.

No amount of data-fiddling will cure this until the profit incentive is gutted from the delivery of health care, and the money changers thrown from the temple.

> No amount of data-fiddling will cure this until the profit incentive is gutted from the delivery of health care, and the money changers thrown from the temple.

Yep.

Another wrinkle is that the readmission benchmark is usually measured on the basis of readmission to the same facility within 28/30 days for the same or a related condition.

If you can shunt the patient to a different hospital, or code the second admission as being for a different condition, you avoid the questionable readmission.

Gaming the coding process can still be a problem in publicly funded hospital systems. Virtually all public hospitals in Australia, for example, pay the substantial licenses fee for the 3M Grouper software.

Public hospitals are funded on the basis of something, and in some (many?) cases, that something is a measure of admitted care provided, calculated using DRG costweights. If the hospital undercodes, and understates its activity, it is at risk of missing its budgeted activity target, and the CEO will suffer the consequences.

Now I know why my hip replacement Dr. took horrible care of me. When released from the hospital one day early and not in too good of shape I went home. After one night at home we called the hip Dr.’s office to tell them of some of the complaints I was having. They said I need to contact my regular Dr. At that point I didn’t have a primary care Dr. so I suffered til 3 am one morning when my wife called the paramedics to take to a different hospital closer to my house but in the same hospital group. There I languished for several days until my wife diagnosed me. I had a spinal fluid leak from the epidural they gave me during the hip operation. When contacting the Dr. weeks after recovery about the additional costs for my medical stay because of his office’s negligence the response I got was “that’s too bad. Things happen.” He didn’t want anything to reflect badly on his Readmissions Record.

Unintended consequences that were entirely predictable.

Times how many thousands?