Yves here. This isn’t the most inspired discussion of MMT, but it does give an idea of where mainstream economists are. The fact that MMT is now being treated as a topic of consideration means it is well beyond the “First you ignore them” stage.

By Inês Gonçalves Raposo, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel who previously worked for the Financial Stability Department of the Bank of Portugal. Originally published at Bruegel

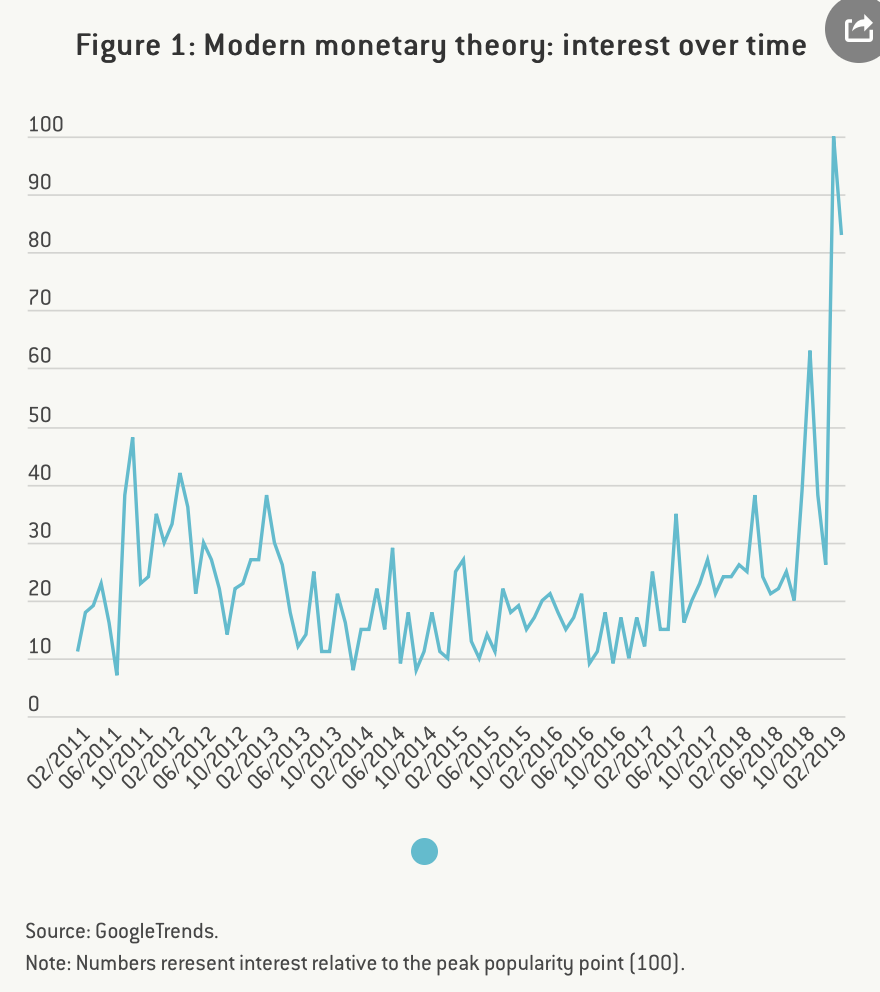

An old debate is back with a kick. The discussion around modern monetary theory first gained traction in the economic blogosphere around 2012. Recent interventions in the US and UK political arenas rekindled the interest in the heterodox theory that is now seeping into mainstream debates.

It is February 2019 and modern monetary theory (MMT), a heterodox theory born in the late 1990s, has made its way into mainstream discussions, on the back of public support from political figures both in the United States and the United Kingdom.

Interest around MMT is now at its peak (Figure 1) and the economic blogosphere and #econtwitter have been having heated discussions on the matter. A few weeks ago, we reviewed some of the opinions around MMT, most of which tied with the debate on US debt. In this post, we gather the main points that have been raised over the past week.

What Is (Not) MMT

Most of the debate has been on understanding what MMT actually is. In fact, the basis for MMT started in the 1940s. Back then, Abba Lerner coined the term “functional finance”. The base premise from which MMT later drew was that, under “functional finance”, fiscal policy should be the main instrument used to stabilise the economy – taxes, and not central-bank interest rates, should be used to remove people’s spending power and thus stave off inflation. This was a view shared by some in the postwar period, as Randall Wray, one of the main authors of MMT, explains.

Wray also summed up MMT in 10 points, two of which have been the main focus of contention.

- Finance should be “functional” (to achieve the public purpose), not “sound” (to achieve some arbitrary “balance” between spending and revenues). Most importantly, monetary and fiscal policy should be formulated to achieve full employment with price stability.

- There is no chance of involuntary default so long as the state only promises to accept its currency in payment. It could voluntarily repudiate its debt, but this is rare and has not been done by any modern sovereign nation.

Jo Michell had something to say on what MMT is not. Michell debunks the claim that “government deficits are necessary and good because without them the means to make settlement would not exist in our economy”:

“This claim is neither correct nor part of MMT. I don’t believe that any of the core MMT scholars would argue that deficits are required to ensure that there is sufficient money in circulation. (…) The macroeconomic reason for running a deficit is straightforward and has nothing to do with money. The government should run a deficit when the desired saving of the private sector exceeds the sum of private investment expenditure and the surplus with the rest of the world. This is not an insight of MMT: it was stated by Kalecki and Keynes in the 1930s.”

As Josh Barro clarifies, though, there is no magical money tree involved. “The government is not constrained by its ability to obtain dollars, but the economy is constrained by real limits on productive capacity.”

Main lines of criticism: Inflation, “there is nothing new about this” and “there is no underlying theory”

As Brad deLong puts it, MMT has a “modest goal” that can nevertheless go wrong, should three implicit assumptions prove to be false: the first one, that the debt market is efficient; the second, that investors react quickly and that inflation will too, should concerns over government sustainability become evident; the third, that investors will only “borrow foolishly” on a small scale.

Jonathan Portes criticised MMT for not accounting for the role of the private sector in determining the level of demand and inflation. Portes takes issue with the claim that deficits are necessary for growth. “Money is ultimately a creation of government—but that doesn’t mean only government deficits determine the level of demand at any one time. The actions and beliefs of the private sector matter as well. And that in turn means you can have budget surpluses and excess demand at the same time, just as you can have budget deficits and deficient demand.”

In his post, Portes describes MMT as the reversal of the traditional management of macroeconomy through interest rates (aka the “Consensus Agreement”). Alexander Douglas argues that this Consensus asymmetrically affects the poor, who have less control over their cash flow.

“When rates are high, they can’t defer consumption; they have bills to pay and necessities to buy. (…) When rates are low, they have neither the spare capital nor the collateral base to take full advantage by making investments the way that rich people can. (…) The poor can’t, in technical terms, optimise over the yield curve anywhere like as well as the rich can.”

The distributional consequences of increasing interest rates have been empirically assessed in the literature by e.g. Amaral, 2017 (“the more meaningful changes in inequality occur over longer periods of time than the horizon at which monetary policy operates and are most likely the result of structural changes (…) while monetary policy may have some redistributive consequences, their magnitude seems to be small”), Ampudia et al. (2018) or Bunn et. al (2018). Meanwhile, Colciago et al (2018) review the literature and conclude that “empirical research on the effect of conventional monetary policy on income and wealth inequality yields very mixed findings, although there seems to be a consensus that higher inflation, at least above some threshold, increases inequality”. Douglas acknowledges that redistributive taxation can compensate for the distributional impact of interest-rate adjustments, but leaves the open-ended question:

“Why not, therefore, use tax to control inflation instead? (…) Why not skip the middleman?”

Brian Romanchuk, on the other hand, takes issue with those critics of MMT who argue that it leads to inflation or hyperinflation. “The whole premise of MMT is that “too much” spending leads to “too much” inflation, and that is to be avoided. The only real debate is how much spending is “too much.” To critics that say that MMT is nothing new, Romanchuk answers that MMT should be seen as building from post-Keynesian theory: “The key point to understand is that MMT is part of a long line of post-Keynesian theory, and in academic circles, is described as such. The ‘MMT’ moniker can either be viewed as a branding exercise, or an attempt to create a consistent body of thought within the wider post-Keynesian literature. This latter step was necessary, since we have to admit that the post-Keynesian project was a practical failure.” Finally, Romanchuk tries to assert the “T” in MMT, naming and expanding on two divergences between neoclassical and MMT economists: their takes on overlapping generations models, and on the inter-temporal governmental budget constraint.

The ZLB Is Where Both Sides See Eye to Eye

There seems to be, however, one instance in which both sides can agree, and that is when the zero lower bound (ZLB) comes knocking at the door. Portes notes that taking fiscal policy as the main tool may be called for under the ZLB, although in his view “that’s no longer controversial, and was explicitly recognised by government policy during and immediately after the 2008 financial crisis”.

In fact, back in October, Simon-Wren Lewis had weighed MMT and non-MMT against a five-question framework and concluded that, whenever the economy is not on the ZLB, using fiscal policy as the main stabilisation tool is less desirable, as it is slower to implement, cannot be delegated and is subject to political incentives. “A potentially strong argument against monetary policy is the lower bound problem. You could argue that having monetary policy as the designated stabilisation instrument gets government out of the habit of doing fiscal stabilisation, so that when you do hit the lower bound and fiscal stabilisation is essential it does not happen. Recent experience only confirms that concern.”

After an intense week of social-media spats, it is unclear where this discussion will lead in practice. Perhaps the most interesting element is that political clout brought mainstream and heterodox to talk to each other. In any case, deLong leaves us with a silver lining – “the government should make it its first priority to use its tools of economic management so that we do not experience either [high unemployment or excessive inflation]; and maybe the government needs to be a little bit clever in how it uses fiscal and when and how it uses monetary policy to keep the task of financing the national debt from becoming an undue or even an unsustainable burden”.

It seems that all the hand-waving from economists is based on an underlying idea that “the economy” can be reduced to some set of “scientific” principles. That seems extremely unlikely to me, since economics is a voodoo-pseudo-science. My question for Brad de Long and others is, why should the people of this country, who empowered their elected Congress to coin money and regulate its value, need to pay interest to anyone for the use of their own money? As Mike Norman helpfully pointed out a couple of years back, the U.S. retired (paid off) $94 trillion of its debt in 2016, and nobody noticed. We need a discussion of why direct federal spending, dispensing with the charade of using debt instruments, can or cannot be made to work.

“need to pay interest to anyone for the use of their own money?”

Agreed, no reason to pay interest for the use of their own money. But, for complete different reasons per the second rule of functional finance:

By borrowing money when it wishes to raise the rate of interest and by lending money or repaying debt when it wishes to lower the rate of interest, the government shall maintain that rate of interest that induces the optimum amount of investment.

There might be an argument for providing an ultra safe interest paying savings vehicle as well.

It is my understanding that your last sentence is the key. The currency issuing sovereign does not need to borrow; it issues interest bearing bonds as a favor to its citizenry as the safest savings asset against which all others denominated in its currency are measured.

In this sense, the indignation behind:

“why should the people of this country, who empowered their elected Congress to coin money and regulate its value, need to pay interest to anyone for the use of their own money?”

is misplaced. We don’t NEED to, but its beneficial for citizens that are savers (in service of income smoothing) that we do so.

No need to only do direct spending, and I agree that having ultra-safe savings vehicles is a good thing. I suggest sending $1,000 per capita directly to the states, interest free – that would be $330 billion a year. I bet that the states, those laboratories of democracy, could find good use for it.

“interest rate” is still being used as a fig leaf for “forced unemployment” and/or “physical degradation of the poor”, which is how the “economy” is currently managed.

Not really sure if DeLong actually gets the fundamentals of MMT right. He worries about national debt from becoming “undue or unsustainable burden”.

On the one hand he seems to be acknowledging that outside of inflation and real resource, there is no constraint on the national government’s ability to spend. If that were(is) the case, paying off the debt (plus interest) will not, in any way, be an “unsustainable burden”. Why the seeming disconnect in the long and the short of it?

What did I got wrong?

DeLong’s criticism is, like Krugman’s, a recyling of Piketty’s r>g relationship; debt is unsustainable when interest income grows faster than national output. Warren Mosler and MMT deal with this by permanently setting the interbank rate to zero and pushing rates below growth along the entire yield curve.

“Warren Mosler and MMT deal with this by permanently setting the interbank rate to zero and pushing rates below growth along the entire yield curve.”

How is that not a prescription for endless malinvestment? With interest rates artificially suppressed for a mere 10 years, there has already been so much malinvestement that Central Banks are now unable to raise rates to any significant degree without crashing markets.

It isn’t artificially suppressed, zero is the natural interbank rate. The Fed artificially pushes the rate above zero.

Interest rates reflect risk, and not all banks are equally creditworthy, nor well capitalized. How, then, can the “natural” interest rate of short-term borrowing between them possibly be set at zero?

Banks only want to hold so many reserves, i.e. “cash”. Any excess is simply dollars not generating incomes, so they seek to loan those excess dollars to a bank with insufficient reserves. Those excess reserves are created by government deficits. If lots of banks have excess reserves (and they always do) they compete with each other to find borrowers, lowering the interest rate toward zero. When the Fed sets a Fed Funds target rate, it is, through monetary operations, draining reserves to push the interest rate up

I should maybe make explicit that the interbank rate is not a function of risk. It is simply a monetary policy tool adjusted by the FOMC in response to macroeconomic conditions and goals.

But my understanding is that the interbank lending rates are used as reference rates in the pricing of financial instruments such as floating rate notes (FRNs), and adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs), etc.

And if that is the case, then holding them at zero would indeed distort markets that use interest rates as a measure of risk.

Not really.

It would just mean that “Libor plus 150 points” would mean 0 plus 150 points, and not some made-up number plus 150 points.

Too bad about Libor.

Also, retail deposit protection means most individuals have no incentive to assess bank counterparty risk and TBTF means the same for big banks. Rates are not risk where there is a state backstop. The squeezed middle of non-financial commercial depositors therefore buys full faith and credit Treasuries and only keeps spare change in the banking system. There is no reason for the yield on Treasuries to be positive – negative yields are still cheaper than guarding warehouses of cash or bullion.

But banks DON’T lend from reserves. They conjure the money from out of thin air. The outstanding loans then show up as assets on the bank’s books. The more people that owe the bank, the wealther the bank appears to be on paper.

MMT isn’t/shouldn’t be just about government debt, which is only half of the picture. The other half is the lose regulation behind credit creation used by the banks that give the illusion of wealth. Often at the expense of real economic output.

Banks don’t make consumer and commerical loans from reserves. They do, however, loan reserves to other chartered banks.

It’s all one big integrated system and the Fed has been using QE as a tool to reflate finance without addressing any of the underlying issues in the real economy.

To the extent that the power of seigniorage has been used to preserve the cash flow on ultimately unpayable debts (my understanding of what QE is), this exercise has paid for rampant mal-investment. Everything from Amazon to Uber to Fracking in the “new economy” strikes me as mal-investment.

The Mosler position is to subject “investment” to democratic control in order to establish “public purpose”, at least as I understand him, Wray and Mitchell. This would make the dollar the peoples money rather than banksters money as it is now and to the extent mal-investment continued it would be subject to popular checks and balances.

Thanks jsn. And the Central Banks and their owners will agree to cede their tremendous power, and attendant ability to generate wealth (often asymmetrically), for what reason(s), exactly?

What with AOC and Sanders, certain people are inclined to attempt democracy. Power has been taken from elites before, even in my lifetime!

They will not cede it — it will have to be wrested from them.

Yes. I see it this way also. In a sense interest rates are the equivalent of gradual QE. And clearly QE is a perverted tactic to begin with. It taps into sovereignty by using the fiat but it can’t achieve sovereignty. Much like the latest financial scam: crypto coins. But it’s all we have had to work with. And malinvestment cannot but follow. Malinvestment is its own reward. There are no returns. Value is replaced by financialism. Kind of a no-brainer. In the end we do a bunch of stock buybacks to keep the corporations from doing a long-overdue faceplant. No? QE is anything but a fiscal solution. Thus QE is not “government” – nor sovereign. Therefore it is not MMT because MMT requires fiscal decisions and action – not financial decisions. QE is a frantic attempt to keep asset prices high to keep the entire financial structure from blowing away.

almost wish we could call it Modern Fiscal Theory

I linked to Mosler’s paper below and I think that is exactly right. Mal-investment is really the issues and that conversation is really only happening on the margins. US cannot make any progress until that is recognized for what it is. Unfortunately, it’s probably too late as the climate change clock is ticking and the best we can do is hit the snooze button.

If you have state-created money rather than private bank-created money, you do not need an interbank rate because the bank is just a payment utility.

Malinvestment can be minimised by the state offering to supply unlimited capital for investment by conducting reverse auctions on the hurdle rate of the manager’s carry. If the auction doesn’t reach the target yield, supply more capital!

Depending on your taste for micromanagement, you could do this broad brush (infrastructure, industrial, housing etc) or finely (early stage biotech, non-ferrous metalworking etc), with different rates for each. The market function of capital micro-allocation is preserved but political choices dictate the relative societal importance of the outputs by dictating the cost of capital.

Logically, any project with a positive return (even zero return!) should be funded as net beneficial but, if you fund most of them, real input costs will rise and the return of the remainder will go negative.

Yes, i think De Long’s issue is only in play if paying the interest on debt is itself so large that the interest payments become inflationary.

@Ben Wolf

Thank you.

Krugman also perpetuates the myth that federal deficits crowd out private spending because it (deficits) will lead to higher interest rates.

Utter bollocks, imo, because as the most recent billionaire tax cut shows, it didn’t lead to any of that – the Fed arbitrarily sets short term borrowing rate anyway and Powell has indicated he’s not keen on making higher adjustment at this time.

“By borrowing money when it wishes to raise the rate of interest and by lending money or repaying debt when it wishes to lower the rate of interest, the government shall maintain that rate of interest that induces the optimum amount of investment.”

That’s basically what conventional monetary policy’s open market operations does. The only difference is that to reduce interest rates the Fed buys existing government debt instead of repaying it, but practically it has the same result.

There are limits, though I find it hard to articulate them.

MV=PQ.

V is very different at Debt/GDP of 10%, 100%, and 1000%. At some point, so you have so much nominal money that it seems the “real” productive economy loses meaning.

Even if interest on the national debt is set to zero, it doesn’t seem like a good idea to give money to poor people so they can give money to rich people so they can buy government bonds and hoard their riches.

When people try to sell something that is a fake, they resort to trying to make it complicated sounding. They obfuscate with semantics about terms, and their meaning. MMT does this all the time, in an effort to get people to believe the debt we didn’t need to create, to have US DOLLARS, is ok. The presumption that the debt created, isn’t a bad idea; is wrong.

Sure, we can keep racking up debt, but it does have a cost. how many new dollars created now, with their own debt attached;go solely to paying the old debt. It is not nothing. If 1 in 5 dollars created go to servicing old debts, that means 1 in 5 dollars could be going to healthcare, or education, or the green new deal .

Those who would minimize that 1 in every 5th dollar might say it is going to investors, and adds equity in some way. Which in some way it might. But then again, the fees charged for all that goes to a financial sector that uses those profits to pervert the american republic, vis a vis campaign dollars and insane executive payouts. As well as huge sums of money altering market fundamentals, to the point there are no fundamentals. It is all about money.

so what america needs, is to get to a system where our US dollars are created WITHOUT debt. AS is possible and preferential. The federal reserve is a private-public entity that enables all the federal reserve system banks access to essentially unlimited capital for virtually nothing. They get the money first, at the lowest interest, and then lend it to everyone else with higher interest. All the way down till it gets to everyone else at the highest interest. think credit cards and payday lenders. The mountain starts at the money tree that these pretend financial virtuosos get to play with. Life ain’t that hard in a rigged game. On top of that banks create money when they make loans, knowing the balances will be restored later, by the money fairy.

So with a national debt right now, at @ 21 or 22 trillion dollars, and 15 years ago it was what 7 trillion….a couple of years before that it was 5. so sure we could keep going, but is it wise. Is it prudent to keep adding debt when we don’t need to? With the associated fees of the financial industry servicing all that debt also keeps expanding, there is a certain segment of the society that says,”YES we can!”…. of course they are bankers, hedge fund gurus and financial services executives….. On top of the heap of wall street gate keepers.

What we really need is to put the federal reserve under treasury department control. As was the plan.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/112th-congress/house-bill/2990/text

“Is it prudent to keep adding debt when we don’t need to?”

The charade of borrowing keeps the bondholders’ income flowing.

It also keeps profits going for the intermediaries of those bonds.

As I understand MMT, it’s not that debt is good or bad – it’s not really even debt, as most people understand it. It’s simply an asset swap, whereas financial institutions will trade one federally-issued security (dollars) for another (treasuries), that will pay out interest in the future. Also, this statement is clearly wrong, from the perspective of MMT:

The amount of money available isn’t a constraint on what the federal government can do. Rather, the government is constrained on the availability of stuff for it to spend money on.

The problem is , is that MMT isn’t practiced by any of our branches of government. The claim MMT makes doesn’t actually apply to any of the branches of government that is in our constitution. Nor is it an actual paradigm that is embraced by the legislative branch that does see the “paying”of the “debt” , as part of “the budget” that diminishes the whole.

And as far as our gov’t being constrained by the availability of things to spend money on….. really? Like what…. they could erase student debt… I think there is plenty of that to spend money on. Or how about medical bills driving people into bankruptcy… there are plenty of them to spend money on… how about schools…. and the list goes on…. just what are these things “that are not available for the government to spend money on”?

Two points. First, MMT is not a policy or set of policys. It is a discription of how monitary systems work based off of observations – including the consquences of current policy.

The government is already constrained by MMT, they just don’t know it. As a result, they make policy that keeps blowing up in our face is ways predicted by MMT.

Second, government is constrained by resorces. Sure, we could print enugh money to send every one to collage. But are their enugh seats to acomidate the rush of new students such a policy would bring? There are only so many seats, and universityes can only grow new capacity so fast.

If every one rushed into university at the same time, with existing capacity, the result would be inflation as every one still has to compeat for limited seats.

the 1st point isn’t true. MMT CLAIMS to be a description of the monetary system, but it isn’t. It claims the federal reserve is a public institution. It claims the money in the US is made BY the government.

If the fed was a part of the gov’t, why do we need to create debt to repay it?

The gov’t could just create the money by an act of law. and it would be done. Is this some form of welfare to work program for wannabe bond dealers?If they wanted to set a rate, they could just set it.and adjust as needed…..

MMT describes a system that is parasitic to the american people, and pretends the parasite is beneficial to the host.

So how is the gov’t constrained by MMT?

Also,

If the gov’t paid for education in the US, we would only be doing what is done elsewhere. And in those countries with paid education for its citizens ,they don’t seem to have any of those issues you imagined.SO what evidence beyond a theory do you have? In fact the cost of education seems to be kept below what we have here in the US.

As opposed to the way it is now, with runaway costs , which deny many the opportunity, and saddle others with debt for decades….which is negatively affecting the economy as a whole today.

You are conflating the federal government’s issuing of bonds with “debt”. Even if the federal government didn’t issue bonds, every dollar it creates is still a debt. A dollar is a promise to pay; that’s a debt. That debt is extinguished when that dollar is removed from the economy by taxation.

The bonds the government issues aren’t debts in the same sense as you or I going to our local bank for a loan. The federal government sets the interest rate it pays on the bonds it issues. They are a tool for setting the interest rate floor. It’s like setting a minimum wage for money: If the government is willing to pay 1.5% on the bonds it’s offering, nobody else is going to offer a lesser amount for their bonds. Why would I buy a lower return (say, 1.25%) when I can get a higher return on a government issued bond?

Mosler and others have argued the natural rate of interest is zero. I reckon that means the government should get out of the bond issuing business because it’s risk-free money for the bond holders. Money for nothing for rentiers. If they want a truly free market, they should buy bonds issued by private sector financial institutions and incur some risk for their return.

If the government stopped issuing bonds, that wouldn’t prevent it from creating dollars. Current legislation requires the treasury to offset every dollar spent with a dollar collected in taxes or a bond. That is a self-imposed requirement. If they want to maintain the double entry accounting scheme, then they could simply create a new instrument we could call a “term deposit”. Instead of buying a bond, a buyer can purchase a certificate of deposit from the Federal Reserve for a fixed interest rate of return.

“Certificate of Deposit” does the same thing as issuing a bond. It sounds nicer. It has the word “deposit” in its name, instead of a bond which is associated with borrowing. But it’s a rose by any other name.

Bottom line though, a dollar is a liability for the issuer (federal government) and that makes it a debt.

The federal reserve creates the dollars, the treasuries are only created to pay the debt owed to the federal reserve to create those dollars. If the federal government created the dollar in the first place, it would not be a debt. If the dollar was created, as a matter of law. as a construct to be legal tender to be united states money,; it in itself would not be” debt”. The federal government created it, out of nothing. And no one would be “owed” for its creation. It would just exist.BY an act of law. That law would have bearing because the constitution originally granted the power to create money to the treasury. The entire rigamoroll you are describing only exists because the private banking system has been given the ability to create our money for us by the federal reserve act. All the rate setting, and circular payment systems that are set up, and apply today only exist because people influenced the system to make it this way.

You say I’m conflating the gov’ts issuing bonds with “debt”? And what else is it?

What you are conflating is the creator of the money i.e the federal reserve…. with the issuer of the debt(be it treasury or cetificate or rose colored paper, or whatever…. it still smell like BS to me). If the federal reserve was the gov’t we would not need to create a debt for it to carry out its function.

So bottom line, the dollar is a debt for the gov’t because it borrows to cover what the federal reserve creates.

What is a dollar?

It is a promise to pay.

That is a debt. It is not an interest bearing debt, but it is a debt nonetheless.

Wray, Mitchell et al have a new textbook coming out shortly. Perhaps give it a read?

a dollar isn’t a promise to pay, it is a unit of exchange.

Is a pint glass a promise to fill?

People are conflating the thing that is created, with what the thing is used for.

Is a hammer a promise to nail?

Money creation by the fed means when the fed creates a dollar, the treasury promises to pay them for it. but there is only law that makes that dollar have value, and be legal tender for debts public and private. And replacing the federal reserve act, with a better one would mean that the treasury can create dollars and not pay anyone for them..and they would be dollars too.

Maybe wray ,mitchell,and mosler need to check out other alternatives like the treasury creating our money instead of the federal reserve and the banks making loans. They ought to stop pretending being a neutral observer absolves one from sin.

A sister theory, Monetary Sovereignty, explains the concept more accurately and more simply.

The MMT twin notions that deficits are not necessary but taxes are, can easily be disproved by history. Every depression in U.S. history has been caused by federal surpluses, nearly every recession has been caused by reduced deficit growth, and cured by increased deficit growth.

1804-1812: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 48%. Depression began 1807.

1817-1821: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 29%. Depression began 1819.

1823-1836: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 99%. Depression began 1837.

1852-1857: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 59%. Depression began 1857.

1867-1873: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 27%. Depression began 1873.

1880-1893: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 57%. Depression began 1893.

1920-1930: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 36%. Depression began 1929.

1997-2001: U. S. Federal Debt reduced 15%. Recession began 2001.

Sadly, MMT has become entangled with a single cure-all, that would not work in the real world: Jobs Guarantee.

Rodger,

Just a comment about your last statement. Please explain why a Job Guarantee won’t work. It’s really not enough to make such a statement without a logical and comprehensive discussion explaining why.

I just finished reading MMT [A Primer on Macroeconomics …] and quite a bit of solid evidence is presented that job programs by governments have a history of long-term positive results. I can only recommend that you take some time to read it.

Once again, that’s a question for which the answer is so straight forward and obvious that it would seem to be a mathematical identity. If the private sector is unable/refuses to maintain full employment and wide spread entrepreneurialism is not possible/desirable, then who else is going to step in to provide jobs? Especially jobs targeted at the many things that need to be done (infrastructure repair and comprehensive heath care right off the bat, among many others) for which the private sector stubbornly will not provide solutions due to lack of profitability.

it’s not just lack of profitability they worry about except in the sense that the gov could provide things cheaper that would erase their ill gotten gains altogether.

Folks, you’re missing the big objection to JG here: It would put an end to “labor discipline.” If implemented, the JG would mean that no longer could employers hold the threat of poverty, homelessness and/or starvation (never mind incarceration) over the heads of their potential workforce. All of these attacks on social safety nets don’t just threaten profits, they threaten dominance.

Exactly. Which is why it will be fought bitterly by those who benefit from the current exploitative arrangements.

And they will fight dirty.

As MMT proponents will tell you, the primary purpose of (federal) taxes is to keep inflation in check. If they’re not necessary, then how do you propose to manage inflation?

If I may, Rodger is big on interest rate adjustment by the Fed to control inflation.

There is of course nothing to prevent policy makers from doing both.

So he prefers unemployment as a buffer stock to regulate the price of money rather than employment.

Still subject to the neoliberal myth that the rich can only be incentivized with additional money while the poor can only be incentivized with increasingly debased material conditions.

I think he’s got the morality backwards: the rich can only be policed by the threat of debased material conditions while the poor could easily be incentivized by some small added income.

May I just say that your second sentence is the most elegant, concise description of this ludicrous disconnect that I have ever had the pleasure of reading.

Just letting you know that I intend to steal it!

Two ways to reduce money supply:

1. Tax more

2. the Government deficit-spends less.

Two ways to increase money supply:

2. Tax less

3. the Government deficit-spends more

Since 97% of the money supply is bank money, then reducing reserve requirements and/or reducing the Fed funds rate would work to increase the money supply too. (This explains why the Fed can’t really manage the money supply too. It only controls 3% of that.)

Two ways to reduce money supply:

1. Tax more

2. the Government deficit-spends less.

Two ways to increase money supply:

2. Tax less

3. the Government deficit-spends more

Sadly, MMT has become entangled with a single cure-all, that would not work in the real world: Jobs Guarantee.

This is like saying I can’t go grocery shopping because I may run out of checks. It’s completely nonsensical.

Is the job guarantee touted as “a single cure-all” as you claim?

No. It’s an employment inflation buffer rather than the current unemployment inflation buffer.

Sadly too many people comment on MMT without much knowledge of MMT. MMT does not state that “deficits are not necessary but taxes are”.

See MMT economist Stephanie Kelton making the same point about Gov surpluses preceding Depressions here: https://youtu.be/c6ss3p4jjI4?t=2254

For readers till trying to grasp the MMT concepts and some real life example of powerful leaders who didn’t get it, the first 40 pages of this PDF is an excellent read.

http://moslereconomics-kg5winhhtut.stackpathdns.com/wp-content/powerpoints/7DIF.pdf

I have a question about inflation.

When I was a child in the UK in the 70s, that “inflation is bad” was pretty much undebatable. All the same I asked my parents: how is it bad? I never got a straight answer or a theory that I found satisfying. For many years I remained confused: why are we generally so sure that “inflation is bad” without being able to say how or in what way?

I later adopted an explanation that I still find satisfyingly cynical and simple. A cryptic political ideology biases the public discussion of inflation and it’s important that the ideology itself is not discussed. Inflation discounts both debts and deposits therefore those with money lose and those with debt win. People with money run the economy while people without have to submit to it. So when rich people are in power, which is most of the time, it’s really important for people holding debt to be convinced that inflation is bad for them, even if it isn’t. And people with money have much more power to control ideology.

I admit that this kind of “theory” is more Adam Curtis than economic. But does it hold up at all?

Cynical minds think alike. Sounds more like a basic truism to me. Of course most people would never want to acknowledge it. The rich for obvious reasons; the poor because it’s a startlingly depressing acknowledgement of their situation. Denial is much more comforting.

I think the premise is faulty. Rich people aren’t injured by inflation as much as you believe, they don’t keep their worth in cash. Go look at Venezuela, the poor and middle class are suffering the most.

Randal Wray has argued that hyper inflation needs to be considered separately. For one thing, it’s quite uncommon—how many cases in the last 100 years? Germany, Zimbabwe, Venezuela? For another, the dynamics are different. Hyper inflation results from external pressures forcing prices up and the government having a shortage of their own currency to pay for things. Normal inflation, otoh, is the result of demand on goods and/or labor exceeding supply, where the demand may be the result of too much government spending.

Precisely — hyperinflation is a difference in kind, not merely degree, from “high inflation” (whatever rate that might be)

Cullen Roche writes about this here:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1799102

The rich hate inflation because it eradicates rentier income. The inflation of the 1970s was terrible for bankers but great for Boomers who bought their first homes with 10% mortgage interest rates and 14% inflation eating away at the principal.

Of course creditors despise inflation. They’re repaid with cheaper money than they lent. The inflation of the ’70s was horrible for them (stagflation!), and discredited the New Deal Keynsianism that had assured U.S. economic growth and brought us the middle class.

Why did it end? A shortage of a critical commodity, brought on by the Arab oil embargo. Daniel Yergin says no more than 3% of the world’s supply was impacted, but the price increases were pretty dramatic. The price of a barrel of oil in 1971: $1.75. In 1982 (the post-70’s peak): $42. That last price is about where it is now, adjusted for inflation. Anyway, cost-push is responsible for most inflations. That’s the conclusion of the Cato study of 56 hyperinflationary episodes. In no case did a central bank “over-print” currency. Always, the shortage of some goods or services, often coupled with a balance of payments problem, led to the hyperinflation. In the case of Zimbabwe, for example, the Rhodesian farmers left, and a country that previously fed itself had to import food. After that is when the hyperinflation occurred.

There is more misinformation in this article and the ensuing comments than one could combat in a lifetime.

@Steven Greenberg. Please, can you define “information” and what do you mean by “mis-“? Thank you.

Steven, I’m with you. I quit reading because the points being made sounded like someone’s ideological beliefs rather than how money really works which is what MMT describes. MMT isn’t a cure-all for monetary misuse.

Re: inflation–inflation of wages is also prevented when inflation is tackled and becomes deflation. Else, why are salaries and wages stagnating and causing people great grief in this time?

Jo Michell’s comment is confusing. Isn’t the idea that, because the issuer of the sovereign currency has to “deficit spend” a currency into existence, and has to tax less then the amount it spent into the economy. Doesn’t that imply that the issuer has to maintain a long-term deficit? Or is Jo just talking about short-term deficits, i.e. taxing more than expenditures per a fiscal year and effectively removing that money from the economy in order to slow an overheating economy?

Jo Michell is maybe best understood as discussing whether further budget deficits are necessary.

Michell quotes Murphy’s point “4. Therefore government spending comes before taxation” and says it’s “sort of true but also not particularly interesting”, then goes on to dispute point 5.

In what I’ve called the MMT “creation myth” (I may have gone over the top there, but I still find the idea useful) we require a primordial deficit to put balances into the private banks’ reserve accounts in the first place. After that, how those balances are managed is a matter of policy, to keep the clearing system going in a fair way.

So that said, Michell’s argument is about the need for particular deficits of particular amounts at particular times, and the conditions he sets out look pretty reasonable.

Setting aside policy desirability, raises questions as to whether the Bernanke Fed’s Quantitative Easing (QE) programs with their related negative real interest rates that have served to elevate the financial markets, together with funding recurring federal fiscal deficits, might not objectively be considered MMT as policy; or if we have some sort of hybrid policy given the intermediary role of the Primary Dealers in their purchases of Treasury bonds and sales to the Fed under the Fed’s Open Market Operations?

At its base the argument over MMT is an argument over who should control money creation: bankers or politicians.

Is this a fair generalization?

That question seems to imply that bankers and politicians are at odds.

More often than not they aren’t. The pols generally agree with the bankers that pay them.

I agree that bankers and politicians are at odds the same way that dems/reps are: on the surface but not really.

I’m trying to boil MMT down to its essence and shifting the power of money creation seems to be it, but I’d like confirmation.

Mabye.

The other possiblity, within the reality described by MMT, is for the people to spend money into existence (congress or politicians can still control how much, or when, but the people do the hardest part of the job – spending it into existence).

To me, MMT is important because it shows that the arguments in regards to “affordability” are misplaced, and the public’s perceptions of things like deficits, public debt and how public and private money is created are inaccurate. The media is hopeless, in general and on these issues.

But, just as important for me is the idea of strongly establishing that private financial capital doesn’t have a monopoly on deciding where money goes in the economy, overall investment decisions. It is just a fact that private interests underinvest in things that bring non-market social and environmental benefits, and overinvest in things that result in (large and exponentially growing) negative non-market social and environmental impacts. There are also lots of investments that require large amounts of capital that require a lot of risk taking, which the state has historically undertaken The development of the internet, computers, satellite and touch screen technology, GPS systems, etc. Mariana Mazzucato’s “The Entrepreneurial State” goes over the central role that the state in the US has played in the development of these things, and many technological breakthroughs. These things cannot be left to private financial capital to decide, and private financial capital does not take into account non-market impacts. I realize that some private interests are using things like shadow pricing of environmental impacts, but who knows what their methodology is. I think it is unrealistic to price all those impacts.

I don’t find most of the critiques of MMT to be logically sound. They are often critiques based on misunderstandings of MMT, although I think most of those misunderstandings are intentional. Austin Goolsbee, for example, going on MSNBC and saying nonsense about MMT. Kelton and Mosler both said that they have had communication with Goolsbee in the past, and he knows better than to say what he said on MSNBC. So, his “misunderstanding” is intentional, and I am sick of people like him in the political system.

The article says “I don’t believe that any of the core MMT scholars would argue that deficits are required to ensure that there is sufficient money in circulation.” All I’ve got to say is “Huh?!”

The money *is* deficits. The deficits *are* money. That’s what they are. People erroneously think national debt is like household debt. It’s more like bank debt.

If you have a bank account, that’s your asset…but to the bank, it’s a liability (debt). When you write a check, you’re assigning a portion of the bank’s debt to you…to the payee. Currency is just checks made out to “cash” in fixed amounts. It appears on the books of our central bank (“The Fed”) as a liability, too.

Just in time.

China has just seen its Minsky moment coming and the debt fuelled growth model has reached the end of the line.

At 25.30 mins you can see the super imposed private debt-to-GDP ratios.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vAStZJCKmbU&list=PLmtuEaMvhDZZQLxg24CAiFgZYldtoCR-R&index=6

Japan was the canary in the mine.

Then the UK, US and Euro-zone in 2008, and finally China.

The sequence of events:

1) Debt fuelled boom

2) Minsky moment

3) Balance sheet recession

Japan has been experiencing the balance sheet recession for decades and they have had plenty of time to study it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8YTyJzmiHGk

Global debt deflation looms large.

Adair Turner took over at the FSA when Lehman Brothers collapsed and this gave him the incentive to find out what was going on.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCX3qPq0JDA

Adair Turner has looked at the situation prior to the crisis where advanced economies were growing by 4 – 5%, but the debt was rising at 10 – 15%.

This always was an unsustainable growth model; it had no long term future.

After 2008, the emerging markets adopted the unsustainable growth model and they too have now reached the end of the line.

What do we do now?

Adair Turner sees Government created money as the only way out, aka MMT.

The money supply ≈ public debt + private debt

There are only two components to the money supply, private debt will be going down with deleveraging. There is only one option.

As Japan found, a private debt problem just becomes a public debt problem if you do it with Government debt. You need Government created money, MMT.

Debt deflation is caused by a shrinking money supply and you should avoid that like the plague. It’s what happened in Greece and the Great Depression.

what does MMT have to do with government created money? The federal reserve creates some of the money, and the same private banking industry(which is what the fed is, just with their public hat on) creates almost all the rest when they make loans.

The government is what creates the debts for the federal reserve to be paid for their services….in the instruments dept. The debt as noted, now above the 21 trillion dollar mark… is what we as a nation have to pay later for the dollars we are using today…

Perhaps taking a step back and looking at the big picture may help. The economic system is human derived system for distributing resources. Now the neocons/neoliberals argue that those that accumulate the most capital (stuff) should be allocated the most resources because they’ve proven themselves by being able to out compete everyone else by whatever means to gain this stuff. Now obviously from the way I’ve phrased this, I’m not all that excited about this method of distribution which since advent of the eurodollar (creditism) in moneyland (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RrKq9b-beWU) resulted in the collapse of capitalsim in the U.S. (https://vimeo.com/user20236372/review/101487179/54bf993e5d) and thus we have also adopted creditism. I’m even less excited about distributing resources based on who can best compete for the most credit. We have even seen this lead to corporations shifting there production from stuff to promises and is why a company like GM had to be bailed out, as while it still made cars, it was being allocated resources based on its ability to make promises. Now as MMT correctly states our government can make endless promises and it is pretty hard to imagine any situation where politicians will ever run out of promises. Now I’ve notice a time or two when politicians have made empty promises that they were unable or unwilling to keep, to be fair I’ve noticed a few corporations do the same especially since the advent of creditism and while I am a big advocate for backcasting, setting an ideal goal for the future, even if it is not currently feasible, and then make decisions as to whether they are getting us closer to that goal or not, I think when we get down to the nitty gritty of working out whether or not to adopt individual policies, that should be done with an accounting of actual resources rather than promises as currently done. Now if I understand MMT this last statement is part of the concept, though I hope those with a better understanding of economics will correct me where I’ve gone wrong.

Brian Romanchuk – “This latter step was necessary, since we have to admit that the post-Keynesian project was a practical failure.”

From the smile on a dogs face too your ears …. I feel a fit of the old John Belushi “Luck of the Irish” spat coming on …

As the rest goes its been a feature watching people talk past each other, some on perches throw sand in others eyes, the perennial wandering goal posts on shifting sands rhetorical device kaleidoscope, down right ideological intransigence, etymological – ontological ownership [tm] based on ex ante [???? – religion] w/ a side of funding dynamics [investor rights – ????] ….

After decades of neoliberalism there is a cornucopia of agents that have made packet or sit in comfy sinecures. Expecting any of this cadre to bend much or acquiesce probably has dynamics similar to asking slave owners to hire locals rather that buy people and then breed them to boot. I mean Greenspan’s milquetoast mea culpa only to get a sweet perch, like all before him, for dirty deeds done cheap considering the squilllions some banked.

I guess it a bit like the post “How Neoliberalism Is Normalizing Hostility” … too which I would offer … Hayek’s thoughts on price discovery necessitating the abolition of altruism meets its inevitable conclusion. Only question I have is this what him and his strove for ultimately or was the deductive process with funding strings a another episode of modified humans partaking of mister toads wild ride.