Lambert here: Measuring happiness… I can see dystopian possibilities, depending on who’s doing the measuring. And why “happiness” as an index of wellbeing? As opposed, say, to “contentment”?

By Sriram Balasubramanian, Consultant Economist, International Finance Corporation. Originally published at VoxEU.

There has been considerable criticism of the general reliance on GDP as an indicator of growth and development. One strand of criticism focuses on the inability of GDP to capture the subjective well-being or happiness of a populace. This column examines new growth models, paying particular attention to Bhutan, which has pursued gross national happiness, rather than GDP, since the 1970s. It finds evidence of the Easterlin paradox in Bhutan, and draws out lessons for macroeconomic growth models.

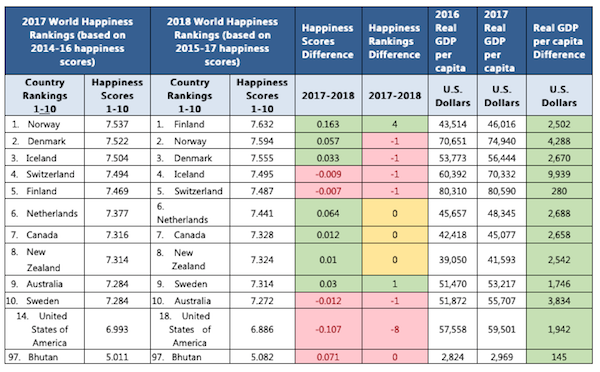

New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Arden, recently proposed the idea of a ‘wellness budget’ for the country, and suggested that wellbeing should be incorporated into their growth agenda (Arden 2019). In a similar vein, William Nordhaus incorporated climate change into traditional growth models, efforts for which he was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics (Gillingham 2018). In a famous article, Easterlin (1974, revised 1995) asked whether “raising the incomes of all will raise the happiness of all?”. This question was raised following the observation that reported happiness levels remained flat over the long-run in countries which had experienced high rates of real income growth. This anomaly was subsequently dubbed the Easterlin Paradox. How relevant is this in today’s times? The following table provides some interesting clues.

Table 1 World Happiness Rankings

Source: Helliwell et al. (2018)

In Table 1, the World Happiness Rankings for different years are compared with their respective real GDP per capita outcomes. According to the Easterlin Paradox (ceteris paribus), the change in World Happiness Scores should not be proportional to the change in real GDP per capita (year-on-year difference) in any given year. If this is the case, then the country with the highest per capita income will not necessarily be that with the highest levels of happiness.

As can be noted in the table, countries such as Iceland, Switzerland, and Australia seem to be in line with the Easterlin Paradox. Bhutan seems to follow a similar trend. Interestingly, the US seems to be following the Easterlin Paradox. This has been largely attributed to the reduction in America’s social capital and the fact that “…certain non-income determinants of US happiness are worsening alongside the rise in US per capita income, thereby offsetting the gains in subjective well-being that would normally arise with economic growth” (Helliwell 2018). As such, it is quite apparent that there is a discrepancy at some level between the perceived positive proportional relationship between the notion of incomes (input) and happiness (outcome). Not only does this introduce the need to look beyond income levels, it also reasserts the need to look at other well-being measurements, such as happiness, as key measures of growth outcomes.

How can this discrepancy be bridged? More importantly, how can these elements be incorporated in a systematic manner into the policymaking ecosystem, rather than merely being proclamations from higher moral ground?

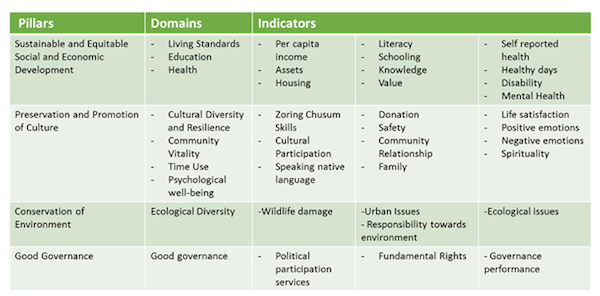

In a new working paper, my co-author and I explore Bhutan’s gross national happiness (GNH) index and its impact on macro-indicators (Balasubramanian and Cahsin 2019). The paper investigates the correlation and causality operating between GNH and GDP, the relevance of the Easterlin Paradox, and the broader lessons that countries can learn from this exercise. The idea of GNH was first proposed by the Bhutanese King in the 1970s (Government of Bhutan 2015), with goals of preserving the environment and emphasising the importance of happiness and collective well-being in the lives of the Bhutanese people. This notion has been followed continuously in Bhutan for almost 40 years. Bhutan’s policymaking is not driven by GDP – it is driven by GNH and the parameters that encompass it. Bhutan’s GNH index tool is a conglomeration of more than 50 indicators encompassing four pillars: sustainable and equitable social development, preservation and promotion of culture, conservation of the environment, and good governance (see Table 2) (Columbia University 2016).

Table 2 The pillars of Bhutan’s GNH index

Source: Centre for Bhutan Studies; Columbia University (2016).

The GNH Commission (GNHC) serves as the central organisation that uses the GNH tool to assess projects and ensure seamless inclusion of GNH at all levels of governance in Bhutan—from the dzongkhags (administrative and judicial districts), and gewogs (residential blocks), to cabinet level deliberations. In a practical sense, it is almost impossible for any big-ticket development project in Bhutan to go through without the assessment of GNHC using the GNH tool. Moreover, the GNHC along with the Government of Bhutan runs a series of GNH surveys at periodic intervals, which help to measure the levels of happiness among the populace, and lessons from these surveys are used in governance and in the administration of the GNHC.

An analysis of the evolution of GNH and corresponding macroeconomic growth over a longer period suggest a positive correlation between the two—indicating that the introduction of GNH indicators actually grew alongside macroeconomic growth. Rather than serving as a deterrent, the two notions seem to have grown alongside each other. While causality cannot be established with existing data, the introduction of GNH clearly didn’t inhibit economic growth.

Is the GNH a perfect model for the rest of the world? Of course not. Bhutan is a much smaller country than most other developing nations, and its economy is much less complex than many other countries. Moreover, completely negating GDP as a measure of growth is moving too far towards the other end of the spectrum. Can GNH serve as a complementary tool to current GDP measures in bigger countries? The answer seems to be a resounding yes. There are three ways in which the concept of GNH could be incorporated into policymaking:

- The first way would be to introduce a concept similar to what Prime Minister Arden proposed – a wellness budget which is underpinned by a scientifically-driven system that measures wellness indicators similar to GNH, which is used to drive policy.

- A second way could be to use a happiness index in each ministry within government as an overriding tool for policymaking. In essence, this could serve as a necessary yet non-intrusive tool to ensure that policies in individual ministries are in line with the broader happiness parameters of the country. This is the current practice in Bhutan.

- A bottom-up approach presents a third option, where a huge awareness drive is created among people of the need for happiness policies. An example that comes to mind is India’s Swaach Bharat initiative to promote cleanliness and sanitation across the country on a large scale. This initiative resulted in rural sanitation increasing to almost 90% (Government of India 2019) in 2018 compared to 35% in 2014. Such initiatives could trigger people to demand such measures in policymaking and could make it an integral part of governance from the grassroots level.

The importance of wellbeing measurements in new growth models cannot be overstated. If we really want to affect the outcomes that people seek, it is important to look beyond GDP and income levels, and incorporate such wellbeing measurements as GNH into policymaking and governance at all levels.

Author’s note: All views mentioned here are personal views of the author and do not reflect the views of IFC or any other organisation.

References available at the original.

Ah, Bhutan – a country I’ve been fascinated by ever since I had college lectures in the 1980’s from one of the first economists to have worked on this index (he insisted on interrupting his statistics lectures with photos of his time there).

There does seem to be a cultural acceptance in Bhutan of low growth/development as a pay-off for greater contentment – I visited a remote valley which had only just been connected to the electricity grid – no power lines were visible because the locals had insisted – at great expense – that all lines be undergrounded because they were afraid they would harm migrating birds.

Having said that, its also a deeply conservative society in very many ways – it was all too obvious that certainly for young Bhutanese its very frustrating to live in a country where everything is so rigid and strict. For all its attractions, Thumphu is not exactly a party zone.

But you have to love a country where, when you ask what type of beer they sell, the reply is ‘two types – strong or weak’. And yes, that’s exactly what they have (no foreign brands allowed).

Cannot decide which I’d rather see sent to Gitmo and tortured – economists who try to impose their algorithms on human behavior….or Elliott Abrams.

Maybe there is a deeper happiness divide. On one side there is a frenzy of excessive wealth and power happiness, and on the other , a sort of peaceful security. Unless it’s just more propaganda, we now see news stories (on F24 lately) about India’s new billionaire class behaving as badly as any Americans ever did. America isn’t even happy when it goes to church. Whereas Bhutan lives in a spiritual reality. Bhutan never put up a statue of Budda holding a torch with the caption, “… send us your weary blablablah.” And there is also the oxygen factor. The air is thinner in the Himalayas. (Isn’t that where Bhutan is?) I’m jaded. I think our social justice drive is the best antidote to discontent. But we could define our goals a bit better. But clearly GNH works in Bhutan.

Well, the Bhutanese did put up an enormous Buddha, but it says ‘bestow blessings, peace and happiness to the whole world’. I’m told it was funded by American Buddhists, but I’m not sure about that.

Is it just me, or does the happiness ranking chart not actually make a good argument for whatever Bhutan is doing? They have a lower happiness ranking than even us here in the US! (All I know about Bhutan comes from Nepalis, who were forcibly ejected from Bhutan for refusing to drop their traditional culture and take up the Bhutanese one – as part of the “Preservation and Promotion of Culture” pillar, perhaps? – so I’m not especially sold on this GNH thing…especially as the originators appear to be doing it worse than countries who don’t even pretend to care about the happiness of their citizenry.)

Happiness is not what we should be aiming for. This mentality, I believe, is an extension of the old utilitarian fallacy that people’s only real drive is pursing pleasure and avoiding pain.

I’m not especially concerned if people are happy or not, as I know plenty of miserable rich people (how do you think Deepak Chopra stays in business?) and plenty of happy poor people. Happiness is a state of mind and improving states of mind is something that is most usefully done on an individual level.

What I am concerned with is creating an environment in which positive states of mind are not hindered by material problems that could be fixed through political action. But focusing on happiness misses the point. If what we wanted was a happy population, we could just set everyone up with a lifetime supply of heroin and bingo! we got ourselves the happiest country evah.

What we need is universal access to free health care, education, housing, clothing, food and companionship. We get those things figured out, and we can worry about whether people are happy later. Something tells me we’ll get better scores after we take care of the material conditions and needs that people face.

We should be focused creating a society in which basics needs are met for all people, thus giving everyone the best chance at being happy, or contented – or at least miserable for reasons other than lack of basic necessities – not on maximizing some arbitrary number, whether it be GDP or GNP. That’s my too scents.

Yes, happiness strikes me as a completely wrong measure – it is completely subjective not to mention extremely variable over time. But it seems like there could be something like “wellness” that takes into account the kinds of things you mention. And I also agree a useful measure would prioritize a set of basic needs for all before any “extra” value accrues to those whose basic needs are already me.

I completely agree with your point that basic needs must be met before even trying to measure ‘happiness’, as this concept is harder to measure meaningfully (although the article describes ways to measure it).

By focusing on meeting basic needs of citizens, the state would free up its population from worries (medical, education…) and would thus mechanically raise ‘happiness’, if such a mechanism exists.

One point that I’ve noted looking at some documentaries of Western people going to remote places to see how they live in ‘harmony with nature and with their own societies’: there is probably a tendency to look at ‘traditional’ societies with some envy (longing for a ‘simpler time’) while completely overlooking aspects such as the place of women in societies, tribal feuds, hardship from manual labour etc. Not sure how people would love to go back to the Western world’s 1920’s or even 1800’s ?

PlutoniumKum also raises this aspect (‘young Bhutanese its very frustrating to live in a country where everything is so rigid and strict’). Regular use of the digital age tools (Youtube, Facebook, and other apps for people younger than me or more connected -Snapp, Instagram) make it hard not to become envious or at least unsecured.

So I am always rolling my eyes when billionaires claim to help ‘poor people’ to access internet instead of meeting their basic needs (clean water/food/shelter). Even if it internet is a fantastic tool that can actually support economic development, it also carries many risks (ie: the uses of Facebook in Myanmar or Whatsapp in Brazil to propagate fake news) that might outweight its positives.

From the post: “Bhutan’s GNH index tool is a conglomeration of more than 50 indicators…”. That’s the trouble with non-GDP “progress indicators” – it isn’t that they’re hard to make up, it’s that they’re too easy. Anybody can concoct a plausible indicator with a spreadsheet and access to UN and/or CIA economic and social data tables. Then I suppose you will need an indicator of the quality of competing indicators!

It’s interesting to see how interest in these indicators has shifted from “underdeveloped” countries to the very much “developed” countries over the last thirty or forty years or so. Back when I was in my twenties, nobody bothered about happiness indicators or progress indicators for First World countries. We just watched GDP growing yearly, and wondered which sort of new car to buy. I suppose a combination of increasing inequality, several traumatic recessions (they’re not unrelated), climate change and ballooning populations have something to do with it, but just maybe a badly flawed model of how governments and societies actually work has something to do with it too. I can’t remember a time when textbook descriptions of how things are differed so much from actual observation of the world as it is. Textbook world seems like a remote fantasyland now.

Anyway, I have no doubt that residents of the older “Third World” (those who have enough to eat, anyway) are enjoying a moment of schadenfreude. Where the US is concerned, I call it “Zapata’s Revenge”.

“Man does not strive for happiness; only the Englishman does.”

― Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols

I just couldn’t help myself….

Just curious, why do these studies always use gross GDP or averages (means), sometimes median but almost never mode.

https://www.purplemath.com/modules/meanmode.htm

In an island country with two inhabitants, one earning $1m and another earning $1, on the average both make $500,000.50.

Could the anecdotal declining happiness in the Anglosphere be due to the declining mode income/wealth?

Just curious.

I had a similar thought. If you use median per capita vs average per capita income/GDP then the “Easterlin Paradox” somewhat rights itself at least for the top seven or so countries that I looked at. It corrects for wealth inequality, and, as we know, the inequality itself is a source of unhappiness. But there are certainly non income factors also at work.

Markets are shaped by two principles: 1) what is produced :: what markets bring in terms of goods and services :: is produced ‘for profit’ {or at least with the expectation of being able to make a profit}; and 2) what markets bring is brought to those willing and able to pay; namely consumers in particular markets.

There is no reason to believe that markets providing for consumers for profit necessarily adds to the realized well-being, objectively or subjectively measured, of everyone. Indeed, that’s not what markets are about, and it has never been what markets are about.

Among other things, this is an argument for non-market production of goods and services whose ‘value’ to human beings is indefinite: not the definite monetary values intrinsic to market production, buying or selling, but one based in supplying what markets can either not produce or supply but is nonetheless ‘worth’ supplying on an egalitarian basis due to human and natural values other than merely monetary ones.

I would think the correlation between GNP and GNH would depend on where you are in Maslow’s hierarchy. If subsistence needs aren’t being met, meeting them by producing more will have a big effect on well-being – happiness, if you will.

OTOH, once everyone has enough, adding more has little effect on well-being. It’s a cliche that being even richer doesn’t make you any happier – if anything, it merely increases the compulsion to have more. And increasing inequality makes everyone worse off – the poor more so, of course.

The article is just a small sample from a body of literature on finding better measures than GDP. For one thing, it includes economic activity that is undesirable – a sicker population will RAISE GDP. And it doesn’t measure costs, like declining resources. Plus, it’s part of growth worship; if we’re approaching limits, more growth makes us worse off; if we don’t feel it immediately, we will.

Why yes of course. Let’s crush workers into the mud, drive their physical standard of living down to the 9th century, and demand that they are happy because they are cultivating inner peace.

Of course, the super-rich that are pushing this disgusting philosophy, would never ever agree to such a bargain. Because being forced to find ‘spiritual happiness’ in the midst of crushing poverty is so only for little people.