Yves here. I can provide anecdotal support the claim made in the post, that parts of the country with high representations of Scandinavians in the population tend to be the most egalitarian and have more mobility. In the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Swedes were well represented (for instance, grocery stores carried knäckebröd). Even though Escanaba was a blue collar town, people were well read and men at the mill belonged to the country club (for its golf course). One of the kids in my high school class also wound up at Harvard and one of my friends became a professor. The working class kids in Escanaba on average were more intellectually inclined than the ones in my next high school, in the upscale corporate suburb, Oakwood, Ohio, where most of the students who were bookish did so do get ahead, not out of native curiosity.

By Thor Berger, Wallander Post-Doctoral Fellow, Lund University and Per Engzell, Postdoctoral Prize Research Fellow, Nuffield College, University of Oxford. Originally published at VoxEU

There are striking regional variations in economic opportunity across the US. This column proposes a historical explanation for this, showing that local levels of income equality and intergenerational mobility in the US resemble those of the European countries that current inhabitants trace their origins from. The findings point to the persistence of differences in local culture, norms, and institutions.

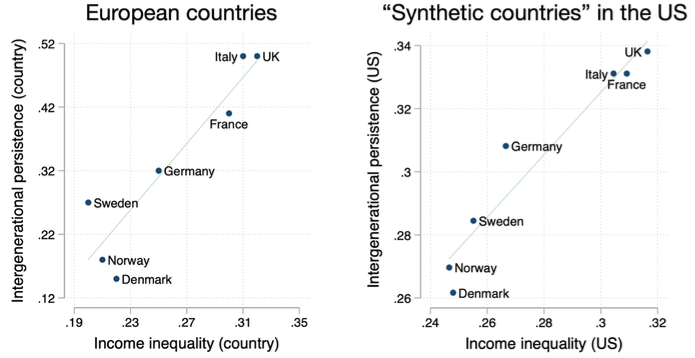

Intergenerational economic mobility refers to the extent to which economic status is perpetuated across generations (Black and Devereux 2011, Jäntti and Jenkins 2015), and has become an increasingly important political concern. Much of this interest is motivated by the worry that growing disparities in income and wealth are reducing the chances for disadvantaged children to rise through the income ranks (Piketty 2014). Country comparisons generally support this view – persistence in income from one generation to the next is higher in unequal societies like the UK and the US, and weakest in the relatively equal Scandinavian countries (Corak 2013). This inverse relationship between income inequality and intergenerational mobility has become known as the ‘Great Gatsby curve’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Great Gatsby curve

Notes: Left panel displays income inequality (measured as the Gini coefficient of family income ∼1985) and intergenerational persistence of income (father-to-son elasticity in long-run earnings for cohorts born in ∼1960) across European countries based on data from Corak (2013). Right panel displays income inequality (measured as the Gini coefficient in family income of parents minus the top 1% share) and intergenerational persistence (the family income rank correlation for daughters and sons born in the early 1980s) based on data from Chetty et al. (2014) for ‘synthetic’ European countries in the US. Synthetic country estimates are US-wide averages with weights assigned based on local representation of each ancestral group, as described in Berger and Engzell (2019).

While country differences are striking, a recent body of work also documents that similar divides characterise areas within the US. In an acclaimed study, Raj Chetty and colleagues found that the extent to which parents’ income levels determine that of their children varies almost as much within the US as it does between countries (Chetty et al. 2014). Proposed explanations for this regional variation have included factors such as family structure, inequality, social capital, and investments in K-12 schooling. Yet, the historical origins of these divides remain largely unknown.

What Are the Origins of the American ‘Land of Opportunity’?

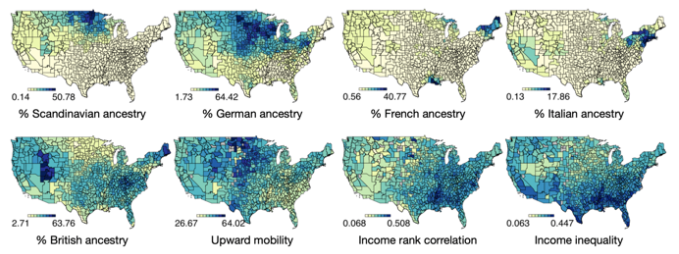

To understand differences in inequality and income mobility in the present-day US, we need to consider the immigration flows that profoundly shaped America more than a century ago. During the Age of Mass Migration (c. 1850-1914), more than 30 million Europeans crossed the Atlantic in search of opportunity. European immigrant groups often settled in regional enclaves, which largely have persisted over time. Today, when Americans are asked to identify their ancestry, what emerges is virtually a map of immigrant settlement patterns from more than a century ago. Scandinavian and German ancestry, for example, is overrepresented in the Midwest, while Americans with French and Italian ancestry are mainly found in the northeast of the country (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Ancestry, inequality, and intergenerational mobility in the US

Notes: Maps display the share of the population that report each European ancestry in the 1980 US Census, upward mobility (the percentile in the national income distribution that a child born to parents at the 25th percentile can expect to attain in adulthood), intergenerational income rank correlation (persistence of family income), and the Gini coefficient of income (minus the top 1%) from Chetty et al. (2014).

Do these places where descendants of European immigrants live show systematic similarities to the countries their ancestors came from? In a recent paper (Berger and Engzell 2019), we show that this is indeed the case. For example, equality and mobility are highest in the Midwest, where Scandinavian ancestry is common. The same goes for every group we study – for example, income mobility is lowest in areas where the population has Italian or British roots.

We use the regional concentration of ancestral groups to create ‘synthetic’ European countries (aggregates of places within the US with a heavy overrepresentation of a given group). Comparing these synthetic countries to their European counterparts reveals a virtually identical gradient in inequality and intergenerational mobility. Hence, the Great Gatsby curve also emerges when one compares levels of income inequality and intergenerational mobility across these synthetic European countries (see Figure 1).

Is It About People or Places?

Can these differences be taken as evidence for differences in income mobility between communities within the US rather than, for example, Scandinavian Americans being more upwardly mobile than their fellow countrymen? The answer is arguably yes, because the black population shows similar patterns of income mobility in these areas. Further support for this interpretation is found when we study outcomes for children that received different exposure to, for example, places with British and Scandinavian ancestry during their childhood, due to family moves. In other words, it seems that European immigrant groups have made their imprint on communities, which shape opportunities for the local population more broadly.

America is unique in that 19th century immigrants broke new ground along the frontier in areas that largely lacked modern institutions. Historians testify to how poor-relief, schools, or healthcare were organised locally around religious communities or other civil associations. Even today, we find a number of differences in such local institutions. For example, the more mobile areas in the Midwest have expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit to a greater degree than the rest of the country. Taxation is also more progressive and there is better access to college education. Thus, in several dimensions, areas in the US where Scandinavian descendants live resemble a ‘Scandinavia in miniature’.

Concluding Remarks

A growing literature finds that the persistence of economic status is strongest in unequal societies such as Britain or Italy, and weaker in countries like the Scandinavian welfare states. While the US ranks among the least equal and mobile countries in the developed world, recent work shows that it contains places that span the global mobility distribution. In this column, we linked these two observations by studying the microcosm of Europe that arose as millions of immigrants crossed the Atlantic and settled over a century ago.

Our results speak to the long-run impact that European immigrants had on their communities (Sequeira et al. 2019) and, conversely, to the historical roots of cross-country differences in inequality as we know them today. Indeed, existing literature documents how cultural beliefs and preferences are transmitted from parents to children and can persist over multiple immigrant generations (Rice and Feldman 1997, Algan and Cahuc 2010, Luttmer and Singhal 2011). While such cultural transmission is well established, we provide new evidence of how different conceptions about the organisation of society can persistently shape places, policies, and opportunity in the long run.

See original post for references

Wow! It’s rare to encounter a truly new idea, but this is it.

Is Ireland counted as “British” in this analysis or did they just leave Ireland out?

Also, Jewish vs. non-Jewish immigrants, especially from Germany.

You won’t find many Americans with Irish ancestry claiming British ancestry (even when they have both). I’m just guessing here but I think its because while there are lots of people with Irish ancestry (its the 2nd largest ethnic group after Germans), they tend to be in urban areas so rarely predominate over all the other groups. There’s probably only a few towns in New England that are anywhere near majority Irish, if that.

That said, Ireland is a very unequal place relative to the rest of Europe, and Irish-Americans tend to live in the grossly unequal North East, so I figure it would follow the trend.

The civil associations Irish-Americans created where Tamany Hall political machines. While they did good things, addressing inequality was far from their priority to say the least.

Appalachia where I live is heavily Scots Irish and the book White Trash seems to take as its premise that this background has a great deal to do with the rural culture of the region. I thought the book and premise a bit simplistic but no question that culture has a great deal to do with our attitudes. Those who condemn the one time and still existing racism of the South don’t seem to understand that people in the region were taught to feel that way by their parents. Teach your children well, as the song goes. It’s the reason that school integration was a central goal of the civil rights movement (and it has worked to a great degree).

One should point also out the common observation that all that Scandinavian solidarity is built on a great deal of ethnic homogeneity. The US problem has always been getting the melting pot to melt.

This. Back in the 90s, a roommate worked for a housing advocacy org in Mpls/St. Paul, historically a center of Scandi immigration. Her job was to apply for apartments, secret-shopper style, so the org could rate landlords on their propensity to discriminate against African-Americans. The Twin Cities rental housing market was apparently so segregated it was known as the Mississippi of the North.

My mother, life-long Republican and descendant of Swedish grand-parents, blamed the “socialist” bent in MN on the dumb Ole-and-Lena’s who maintained their village mind-set of caring-through-conformity post-immigration. In her opinion, worldly-wise people knew better than to just hand money out to strangers. I thought about that a little when reading Tuesday’s piece about trust in society, and cat sick’s comment that keeping business (or wealth) within networks is a way to mitigate risk.

I’m sure you know much of this, and may know all; but it wasn’t clear to me whether you consider “Scots-Irish” Irish and the entire summary may be useful for other people interested.

“Scots-Irish” doesn’t mean “Irish” in any sense worth noting, it means “Scottish from Ireland”; a better name is “Ulster-Scots”. The relevant ancestry group in the current US is a mix of Scots from Ulster/Northern Ireland and Scots and English from the Scottish Lowlands and the Scotland-England border (from where some went to Ulster; the Scottish border region is a.k.a. Southern Uplands, sometimes called part of the Lowlands despite not being “lowlands”).

This larger group can be called Borderers/Border Reivers (their culture started from the England-Scotland border conflicts, part of them was used as a buffer between English lords and Irish serfs in Ulster, parts from both regions went to the US and were the main pushers of the border against the Amerindians – Andrew Jackson being their first president).

If they don’t get a category separate from British and Irish in a list, they should belong to the first instead of the second (though I’ve heard *nowadays* some miscategorize themselves as “Irish” if given a list), but are best separate; if there’s a “Scottish” category, they still are very different from most Lowland Scots (the majority in Scotland, among whom the Scottish Enlightenment happened); in the ancestry lists where people can claim to be of “American” ancestry, the area for that (a.k.a. the Appalachians) basically shows them.

I got most of this from Albion’s Seed, whose author is sometimes accused of hating the Borderers; I don’t think that’s true – he’s certainly critical of a lot of stuff, but explains it in terms of a history of oppression and conflict, and respects their traditions of freedom; if he hates any group he describes, it’s the Cavaliers. (Which I happen to fully agree with.)

Talking about “rural” is definitely simplistic – rural Ulster-Scots, rural Germans, rural Egyptians, and rural Han have basically nothing in common.

The vast bulk of Irish immigration to the US took place pre-WWI when Ireland was part of the UK. So I was asking whether the authors lumped the Irish with the British.

Wow-2. Egalitarianism is a moveable feast. I like this leitmotif because it’s what I have always felt. I suspect when actual events are removed by two or so generations we can’t really access the thinking that gave us our attitudes – but we still have our persistent attitudes. Cultural beliefs (a complex category of thought no doubt) persist over multiple generations. I submit cultural beliefs persist over the entire evolution of us guys. All that “garbage” DNA? That’s environment become cultural kept in storage for those same circumstances to reappear. DNA is a frugal beast. Interesting that Italians have the least equal societies. In light of the fact that Rome – the once Imperial Blob – was swept away completely – never to return. Is this what is now happening in the UK? I think this research integrates in-group and out-group assimilation of differences when it says the US is not an equal/mobile society but contains islands of equality. Diversity pushes us forward, as usual. Love the Great Gatsby Curve – finally a graphic I can grok!

The idea isn’t new. For a (decades-old, and by no means the oldest but IMO the best) book-length treatment of similar divisions between British people themselves, see Albion’s Seed (for a less detailed one that included some more peoples, American Nations – though contrary to the subtitle, it only covers Canada and US).

Growing up along the route of the Great Northern RR, I was told that they were responsible for a lot of immigration from northern europe into the US… At least along the northern tier.

http://www.mnopedia.org/thing/great-northern-railway

Along the sparsely populated right of way through Minnesota, North Dakota, and Montana, the Great Northern bought land from the federal government. It rarely, however, resorted to land grants, instead selling parcels to newly arrived immigrants—most from Germany and Scandinavia.

The railroad created special “colonist” or “emigrant” cars—passenger cars appointed in Spartan fashion—to inexpensively convey immigrants to their new farmsteads. The railroad advertised Minnesota land, and many immigrants bought plots reclaimed from swamps. The state granted over two million acres of swampland to aid in railroad construction. Some of the larger grants that became part of the Great Northern included lines from St. Paul to Duluth and from St. Cloud to Hinckley.

People from the mountains of West Virginia and eastern Kentucky have high economic mobility (by US standards) with predominately Scots-Irish ancestry. Would be interesting to know if the Scots-Irish have higher economic mobility by UK standards. If not, this group wouldn’t seem to follow the pattern.

I don’t have current data, but the history would suggest yes – the people that became known as “Scots-Irish” in the US lived in much less stratified populations than most English (therefore most British). Albion’s Seed deals specifically with intra-British differences among the groups that founded the US, the 4 main parts being about Puritans, Quakers, Cavaliers and their serfs, and Borderers (“Scots-Irish” or people who claim “American” ancestry in surveys). Note that the descendants of Borderers still in the UK (particularly between England and Scotland) may have diverged from the historical trajectory relevant to their relatives in the US (and converged towards English/Scottish in general) due to the area having been pacified (since their older culture was defined by constant conflict).

Is the article attempting to link social mobility to the welfare state or social programs?

“To understand differences in inequality and income mobility in the present-day US, we need to consider the immigration flows that profoundly shaped America more than a century ago. During the Age of Mass Migration (c. 1850-1914), more than 30 million Europeans crossed the Atlantic in search of opportunity

“A growing literature finds that the persistence of economic status is strongest in unequal societies such as Britain or Italy, and weaker in countries like the Scandinavian welfare states….

“this column, we linked these two observations by studying the microcosm of Europe that arose as millions of immigrants crossed the Atlantic and settled over a century ago.”

What is the history of social programs and the welfare state in Scandinavian countries? 1850 to 1914 is the period of migration mentioned. Why did they leave?

Important question. Thank you.

Economist Lester Thurow has some thoughts about this in his 1999 book, ‘Building Wealth’, which is primarily about how countries become wealthy. Thurow says that the populations must be right sized. Scandinavia was incredibly poor when large percentages of the populations of Sweden, Norway, and Denmark emigrated. Once the population was the right size for the available resources, the Scandinavian countries became wealthy.

I would exchange most of the recently arrived people in California–post 1965–for those in the Upper Peninsula.

How do we arrange it?

Here’s where inequality began in the U.S. IMHO. The demographics of the maps reflect that.

https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/sns-wp-blm-immig-comment-13885bda-6929-11e5-bdb6-6861f4521205-20151002-story.html

So all I have to do is get a bunch of Scandinavians to move to Memphis and Mississippi Delta? I’m feeling lucky, better buy powerball lottery ticket too!

I’m curious, was Irish Ancestry rolled into British Ancestry? If so, it seems that would be a mistake.

I would totally attend a NC meetup in the Upper Peninsula (as long as it wasn’t winter)

I wonder if the north euro heredity, in this study, is a proxy for Midwest/great-lakes/Canada-border location… the industrial history of the US followed the lines of the waterways… and you have to figure also the history of labor movements, and more.

Interestingly, most of the 2020 swing states will be here. Looking forward to having the impossibility of single payer explained to an audience near the CA border….

Regarding a certain book I recommended in replies to multiple other people, here’s an excellent review/summary: https://slatestarcodex.com/2016/04/27/book-review-albions-seed/ .

(Though it doesn’t include my favorite story:

” During World War II, for example, three German submariners escaped from Camp Crossville, Tennessee. Their flight took them to an Appalachian cabin, where they stopped for a drink of water. The mountain granny told them to “git.” When they ignored her, she promptly shot them dead. The sheriff came, and scolded her for shooting helpless prisoners. Granny burst into tears, and said that she would not have done it if she had known they were Germans, The exasperated sheriff asked her what in “tarnation” she thought she was shooting at. “Why,” she replied, “I thought they was Yankees!” “.

Note that during the US Civil War, many of the “Yankees” were literal German immigrants.)