Yves here. This article has a significant finding. It contends that while the shift of manufacturing jobs from the US to China did create a tremendous number of jobs in China, it did not lead to an increase in manufacturing wages.

This would seem implausible until you remember that China had (and still has) hundreds of millions in the hinterlands working in substance farming. These workers could move to industrializing areas and get higher wages, which kept manufacturer from having to compete for workers to fill demand from the US. To put it another way, the great increase in living standards in China was due to hundreds of millions from the countryside being able to earn manufacturing-level incomes, and not to global demand for Chinese goods also increasing those incomes.

By Harald Hau, Professor of Economics and Finance, University of Geneva, Difei Ouyang, Ph.D. candidate in Economics, University of Geneva, and Weidi Yuan, PhD Candidate in Economics, University of Geneva. Originally published at VoxEU

Trade between the US and China is widely thought to have contributed significantly to the decline in US manufacturing employment between 1999 and 2007. Flipping the point of view, this column examines the impact on China of the growth in trade and finds that for every US manufacturing job lost, almostsix new Chinese manufacturing jobs were created. International trade did not contribute to faster wage rises for Chinese industrial workersbut instead channelled agricultural and non-participating workers into the industrial labour market.

The last two decades of trade globalisation generated a large rise in imports from low-income countries like China to the developed world. While its negative effect on manufacturing employment in high-income labour markets is well documented (Autor et al. 2013, Bloom et al. 2016, Dauth et al. 2014, Pierce and Schott 2016) and frequently referred to as the ‘China Syndrome’, its flip-side effect on labour markets in China has not been subject to much empirical scrutiny.

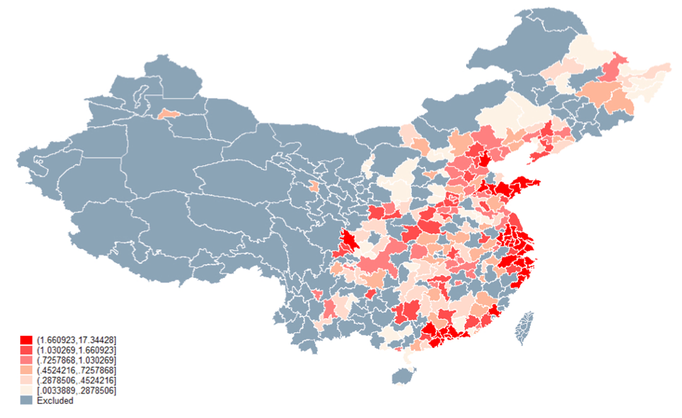

New research by two of us (Ouyang and Yuan 2019) relates the surge in Chinese industrial exports to changes in China’s local labour markets. Analogous to research on the import exposure of US commuting zones by Autor et al. (2013), we divide China into prefecture-level cities and construct measures of export exposure based on a city’s initial industry specialisation. This method yields a detailed map of geographic export exposure depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Geographic distribution of export exposure per worker, 1999-2007

Similar to America’s commuting zones, trade exposure varies greatly across Chinese cities. The 17% most-export-exposed cities (in red) witnessed on average an increase of US exports by $830 million between 2000 and 2006. This compares to only $22.76 million in additional US exports for the 17% least-exposed cities (in beige). Many of the most-exposed Chinese cities are concentrated in coastal regions, but they can also be found inland with stark differences between neighbouring prefectures.

Methodological Issues

As export growth can influence local economic activity and vice versa, any causal analysis requires a so-called instrument, namely, variables that proxy for export exposure without being influenced by Chinese labour market outcomes. Calculating export exposure based on the export growth from other emerging economies to the US provides such an instrument because other emerging countries also benefited from strong US product demand.

A methodological concern is that China’s dominance for some manufacturing exports may generate negative externalities on the export growth of other emerging countries, which would invalidate the estimates. We address this issue by showing that variation in China’s potential export taxation – the ‘NTR gap’ documented by Pierce and Schott (2016) – significantly alters Chinese sectoral export growth without a corresponding effect on the export growth of other emerging countries. Export externalities across emerging markets therefore appear to be of limited economic significance.

Manufacturing Employment Growth: China Versus the US

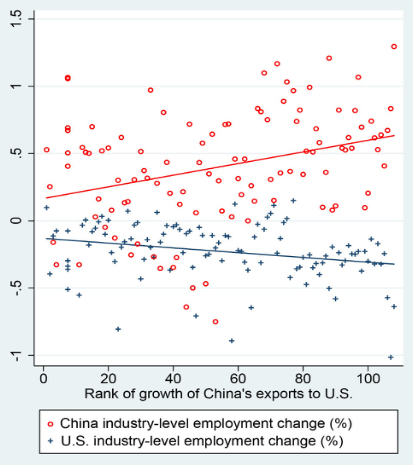

The main analysis draws on China’s annual survey of industrial firms (available for the period 1998-2007). In Figure 2, we rank 112 different manufacturing industries by the strength of their US export growth. Red circles denote the industry-specific employment growth in China and blue crosses denote the corresponding employment change for the US. Two-stage least square regressions show that a one-standard-deviation increase in export exposure per worker is associated with a 0.38 standard deviation in the change in industrial employment as a share of working-age population.

Figure 2 Employment growth in China versus the US by industry rank in export growth, 1999-2007

In the paper, we also undertake a city-level analysis using aggregate city-level statistics – a Chinese city (i.e. prefecture) at the 75th percentile of export exposure experiences an increase in the ratio of manufacturing employment to the working-age population by 4.5 percentage points compared to a city at the 25th percentile. The aggregate analysis reveals that China’s export growth created approximately 12.2 million new manufacturing jobs. For comparison, the corresponding decline for US manufacturing employment is only about 2 million (Autor et al. 2013). This means that every US manufacturing job lost to trade with China came with the creation of up to six new manufacturing jobs in China. The much lower labour productivity of Chinese workers accounts for a large part of this important asymmetry between job destruction and job creation. Industrial wages are roughly ten times higher in the US than in China.

The Big Local Labour Reallocation

Interestingly, Chinese regions with a surge in manufacturing employment do not show a significantly higher population growth to the extent that we measure it correctly. This may be explained by China’s hukou system, which imposes tight controls on migration flows. So where do China’s new manufacturing workers come from?

City-level labour statistics show that cities more exposed to the US export surge experience an additional expansion of service-sector jobs (presumably due to higher demand from an increased working population) – each new manufacturing job contributes approximately 0.68 new service jobs. In the absence of economically significant (measured) migration, this overall increase in the local workforce coincides with a strong decline in local agricultural employment and non-participation in the labour market. However, we cannot exclude that clandestine migration flows also play a role in sustaining a highly elastic labour supply.

Employment Growth Without Sectorial Wage Growth

Surprisingly, a city’s export exposure has only a small and negative effect on the average local manufacturing wage. The differential (log) wage growth is -1.2% for the period 1999-2007 when comparing the 75% and 25% quantile of export exposure.

Yet, this negative average-wage effect does not imply that China’s low-skill workers are worse off due to increased exports. The small negative wage effect of exports suggests a very elastic labour supply as well as a net labour market entry at (or near) the minimum wage. Previous research has documented a large income gap between agricultural (rural) and non-agricultural (urban) sectors in China (Meng and Zhang 2001, Sicular et al. 2007, Brandt and Zhu 2010, Meng 2012). Low-skill agricultural or unemployed workers benefit most when their city of residence experiences a positive export-demand shock – their income and welfare gains are substantial even if they find employment at (or below) the average manufacturing wage.

Summary

The annual value of China’s exports to the US increased by $240 billion from 1999 to 2007, whereas China’s imports from the US grew by only $40 billion. Such a rapid and asymmetric surge in trade influenced not only the US labour market as highlighted by a growing literature, but similarly transformed the Chinese labour market. The data suggest a dramatic employment increase in export-led industries and cities where these industries were initially located. Partly due to a much lower Chinese labour productivity, each job lost in the US is associated with up to six new manufacturing jobs created in China. Much of the new manufacturing employment in China goes to local workers previously employed in agriculture or not participating in the workforce at all. A highly elastic local labour supply also explains why the export surge did not create any pressure on the average industrial wage. This contrasts with the strong negative wage effects of trade identified in the US manufacturing sector.

See original post for references

I would like to see what the graphic looks like for the period 1980-2017.

I remember walking into a very large warehouse in the early 1980’s and seeing what looked like a couple acres of machine tools lined up, I was told to be shipped to China.

By 1999, the move was well developed, and formalized, by that I mean banks wanted to know that your business plans included manufacturing in China, or why the hell not.

I’m sure the most interesting parts of the story are not portrayed in that graphic, how it began, and where it’s heading.

And some people still think the market was making all the decisions? Free marketeering? Not policy, nothing to see here. Offshoring? No. That wasn’t policy either. Well, so bank policy at the time was simply prescient about the future? I would love to hear more of the story not portrayed in this analysis.

For anyone interested in learning more about jobs and China I would suggest looking up David Autor at MIT I think. He has written extensively about US labor and manufacturing in relation to China. The post above delves into more import/export issues as well and I am not sure whether Autor covers that but he is an economist so he might. I just know him from his writing on the exporting of jobs to China and the effects on US labor.

> . . . banks wanted to know that your business plans included manufacturing in China, or why the hell not.

In the 90s, Walmart was a huge destroyer of North American manufacturing jawbs by amplifying that sentiment to the point that if the goods being produced weren’t being made in China to the cheapest and lowest standards possible, they simply refused to carry your products.

As I read this I couldn’t help thinking about how overpopulation defeats the entire capitalist paradigm. It is to China’s credit that they promote “lower productivity” as opposed to hyper competition between firms. That’s a good remedy but it won’t solve the problem. I also think it was a miscalculation to say that one job lost here, one very productive worker, was worth 6 in china – I think they forgot to include the support jobs here so maybe it was a 6 to 6 transfer. Our famous productivity could be a subsidized productivity. And there is a very non-capitalist driver of all this transferred productivity and that is that it is being driven by credit, consumer credit here in the US. The whole thing is folly. Not to mention that China needs all the domestic agricultural production it can promote. And not to forget, all these export enterprises are located on the coasts where they risk being flooded out. And all these contradictions are just failure waiting to happen. Besides which, China can’t begin to ever raise living standards with so many people available for cheap labor. This is a case study in inefficiency and malinvestment. And it has worldwide repercussions.

I also think it was a miscalculation to say that one job lost here, one very productive worker, was worth 6 in china

And I’m not even sure they said that. The, um, “money” quote:

that for every US manufacturing job lost, almost six new Chinese manufacturing jobs were created.

China did not sell everything they make to the US. People don’t stagger out of their unlighted hut, mount a donkey, and go make a 4G TV. Some of them built light bulbs, highways, buses and trains, etc. The US of course never sells much of what we make to China. So that sentence doesn’t tell us anything.

Do I have a point? Not really, but that just threw me off. Near the very end is a much more useful statistic:

The annual value of China’s exports to the US increased by $240 billion from 1999 to 2007, whereas China’s imports from the US grew by only $40 billion.

Now that’s an “ouch”. Worse, China exports more and more “fancy” 1st world things to us whilst we export like soybean. Yes farming is (very unfortunately in many aspects) not a low-tech occupation, but it isn’t the same. Hey, but we have F35’s for football flyovers so it’s all good.

There are some economic thinkers who would argue that a trade deficit is a benefit — rather like the tribute of empire.

Just sayin’ …

China, Germany, Japan, Canada, etc. all are willing to give Americans physical stuff for cotton paper with green ink (which theoretically could be defaulted on/made null) is kinda amazing.

Just saying too.

You currency cannot be the world currency without a trade deficit.

Thus:

You cannot aspire, nor become, a global hegemon without a trade defect.

In hindsight one can see the plan.

Speaking of soybean exports from the U.S. to China, I recently examined a container which was shipped from China to the U.S. and damaged in transit. (I was working for the insurance adjuster). The contents of the container? Soybean meal destined for some processor in the U.S. for ultimate consumption in the U.S.

So, the U.S. ships raw soybeans to China, the Chinese process the soybeans, then ship the processed soybeans back to the U.S. for consumption here.

What is wrong with this picture?

I wonder how much of this was due to the uncoordinated efforts of guys already on the ground in places like HK and Shanghai who were looking for ways to ride the next big wave, even if they had to create it themselves. Recall there was quite a bit of geopolitical maneuvering going on back then, with priority being given improving relations with China (and later, India). A perfect opportunity for business development wonks to beat the drum in the media, at conferences and in meetings, while collecting impressive consulting fees (or book advances). The end result was that a lot of rural Chinese were lifted out of poverty, and a relatively lucrative international situation for a whole lot of years. The demand side problem created by gutting working class jobs in the US was kicked down the road by making consumer borrowing as natural as breathing, which thrilled the hell out of the banks.

Good post, I just want to nitpick:

>a lot of rural Chinese were lifted out of poverty

By some measurement of poverty. Now they jump off the roofs of their nice new buildings, so I gotta wonder about the “lift” they really got.

Maybe, but debt has always driven consumer borrowing. Most of those jobs weren’t middle class either, they were working class. Some areas like Auto still have kept up, the rest ,not so much.

When will China or any other country decide to grow pot to employ peasants and earn hard currency? At some point domestic political or social concerns might be offset by employment or currency concerns, even if that drives down prices due to oversupply. /only half-s

You’ve pointed it out but not explicitly.

Believe this was meant to say “subsistence”.

This study may also hold some othre novle concepts. Reeading this, I keep invisoning the US industerlization of the 1910s. Here too, subsitence farmers began to migrate to the cities for higher paying factory work.

But where did the production go? In the US in 1910, that production was consumed domesticaly, where in China that production was largly exported. Ialso note that USfarm labor was displayed by agricutural industrealizatin. Where China’s farmers are still largly using hand tools and beasts of burden.

This thinking had me questoning weather the study’s production picture is complet. Shouldn’t agrecutural production also be included? How much productin is “self-consumed” vs being exported? (Ithink they did say they took that one into acount.)

Just some random thoughts.

“In the US in 1910, that production was consumed domesticaly, where in China that production was largly exported…”

Just imagine what would happen if they raised incomes and created billions of hyper-consumers “American style.”

I always wondered if that wasn’t American Corporation’s “American Dream.” It was the other side of their interest in China – other than cheap labor (the contradiction chokes me!!!). America does nothing but imagine everthing in its “image.”

While the USproduction in 1910 was consumed domesticaly, it wasn’t consumed evenly, and not by the workers.

But this paper raises the question of how that productin might have been consumed regionaly.

As Isaid before, much of that rual labor had been displayed by mechonization. Suggeting that at least some of that production was being consumed in that sector.

As you said, why didn’t China’s rual farmers receve the same benifit? I suspect several posible answers. 1) China’s production was largly dictated by corpreate quotas. And they would rather make apple phones rather than ox drawn plows.

2) Transitional technoligies. In 1910, “hich teck” plows were ox drawn. Soon replaced by steem powerd tractors and so forth. Whilel today, the gap between self subsitence farming with “home made” equipment and GPS driven 40′ wide tractors are huge, with no imtermeate tehnoligies being produced. Chinese farmers may be willing to updrade, but the jump may be too radical.

3) Finacing. The credit struture was very diffrent in 1910 than today. Chinese farmers simply do not have the money to upgrade. Only large corperation have access to that kind of capital.

The arguements is one-sided and myoptic. Causation of the move from farm to urban is not needed. The people have to leave the farm in cycles. The land has to be rejuvenated, but the near farmlands are already occupied, no more slash and burn. But the people need to eat, so they move, and find work in the city, while the land rejuvenates. The young move because they are taught not to be farmers.. does a programmer push a plow, to eat? And the government rewards their brightest, until they fall out of favor.