Yves here. Even though most readers have likely spent enough time in large organizations to be able to vouch for the validity of the Peter Principle, the plural of anecdote is not data! It’s useful to see a little study prove out what I anticipate is widely-shared experience.

Of course, the factor that keeps Peter-Principle-type behaviors going despite the fact that more senior management ought to know better is perceived fairness. How can you not promote the best salesman, or coder, or field inspector, when not promoting the best one will demotivate their peers by showing that management doesn’t appreciate doing your job well?

By Alan Benson, Assistant Professor, Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, Danielle Li, Assistant Professor, MIT Sloan School of Management and Kelly Shue, Professor of Finance, Yale University. Originally published at VoxEU

In 1969, Laurence Peter and Raymond Hull published The Peter Principle, proposing a farcical theory of organisational dysfunction. The Peter Principle, they explain, is that organisations promote people who are good at their jobs until they reach their ‘level of incompetence’. Fifty years later, Peter and Hull may find plenty of examples of people who occupy important managerial positions because of success in some radically different arena.

In principle, there’s nothing wrong with putting successful people into the highest positions. If the best basketball player makes the best coach, then a coaching position may be the best way to magnify that person’s talents. Similarly, if success in movies or real estate translates into success in governing, then the biggest moguls should occupy the highest offices.

The crux of the Peter Principle is that success in one arena doesn’t necessarily translate to the next, though promotion decisions are often based on a worker’s aptitude in their current position, rather than the one he or she is being promoted to perform. It’s no wonder that the Peter Principle is especially well-known in technical fields – from engineering, medicine, and law – where cases of poor managers who were once excellent individual contributors abound.

If it is accurate, then the Peter Principle bodes poorly for organisations, in light of a growing body of research documenting the important role that good managers play in building and sustaining productive organisations. Lazear et al. (2015), for example, find substantial variation in the quality of individual bosses, with the best bosses increasing the output of their subordinates by more than 10% relative to the worst bosses. Similarly, Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) show that variation in management practices can explain much of the overall variation in firm productivity across countries. These papers suggest that firms face potentially large productivity losses when they promote workers who lack managerial ability.

Empirical Evidence on the Peter Principle

In our research, we examine the extent to which firms promote workers who excel in their current roles, or whether they promote those who have the greatest managerial potential (Benson et al. 2018). Using data on worker- and manager-level performance for almost 40,000 sales workers across 131 firms, we find evidence that firms systematically promote the best salespeople, even though these workers end up becoming worse managers, and even though there are other observable dimensions of sales-worker performance that better predict managerial quality.

We study salespeople for two main reasons. First, it is a classic setting in which the confidence, charisma, and persistence it takes to be a good salesperson are different from the leadership, strategic planning, and administrative skills it takes to manage sales teams. Second, the sales setting allows us to measure individual performance both as individual contributors and as managers.

In particular, we measure a sales worker’s performance as the amount of revenue he or she generates for the firm. We measure a sale’s manager’s performance as his or her ‘value added’ to improving the sales of his or her subordinates (controlling for other factors such as demand, and a worker’s baseline sales ability).

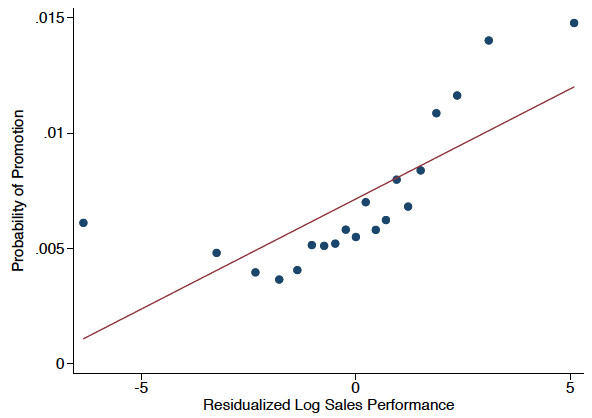

Figure 1 Sales performance and probability of promotion

Figure 1 illustrates our main empirical finding. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we find that sales performance is highly predictive of promotion. This can be seen in the top panel of Figure 1: a worker’s likelihood of promotion steadily increases with higher sales performance in the prior year. A worker who sells twice as much as a colleague is about 15% more likely to be promoted in that month.

This simple fact need not be evidence of the Peter Principle – if the best sales workers also make the best managers, then there is no contradiction between promoting the best worker and the best potential manager. What is striking, however, is that – among promoted managers – pre-promotion sales performance is actually negatively correlated with managerial quality. A doubling of a manager’s pre-promotion sales corresponds to a 7.5% decline in manager value added; that is, workers assigned to this manager will see their sales increase 7.5% less than workers assigned to the manager who was a weaker salesperson.

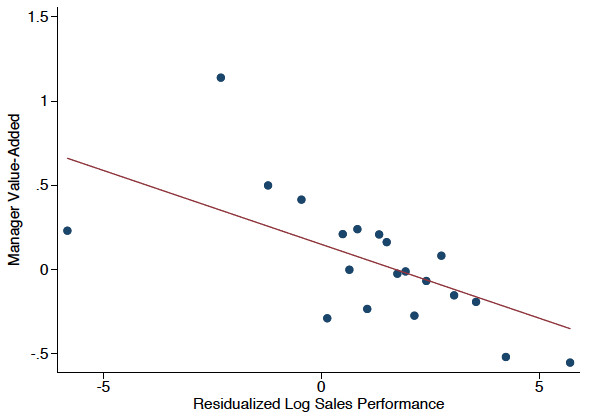

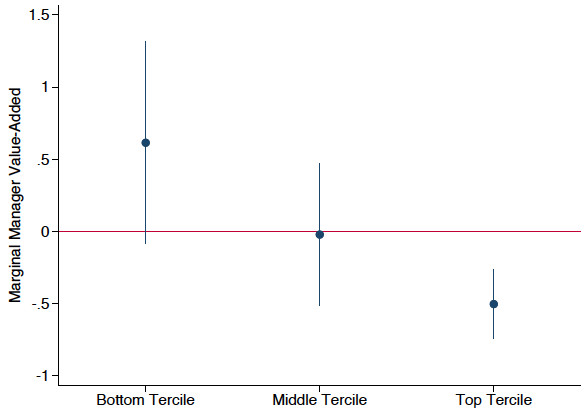

We show that this pattern is likely driven by the fact that firms hold high and low performing sales workers to different standards when making promotion decisions. This is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the estimated manager value-added of managers who were just barely promoted. The quality of these marginally promoted managers tells us about the promotion standards that firms apply to different types of workers: if a firm will only promote a low-sales worker if she has exceptionally high managerial potential, then the marginally promoted low-sales worker is likely to make a great manager. Similarly, if a firm will promote high-sales workers even when they are unlikely to be good managers, the managerial quality of the marginally promoted high sales worker will be quite low. Figure 2 shows that, indeed, top salespeople appear to be held to lower standards. In essence, whether they know it or not, firms appear to be discriminating in their favour when making promotion decisions.

Figure 2 Performance as a manager by performance as a salesperson

By contrast, we identify another measurable worker attribute – teamwork experience – that firms can use to predict managerial potential. We observe teamwork experience by looking at how credits for a single sale are shared amongst workers. Sales workers with more team experience are those who collaborate more frequently on a given sale, for instance by generating a sales lead and then passing it on to a colleague, or by maintaining contracts initiated by others. We find that firms are not more likely to promote workers with more teamwork experience, even though these workers tend to make better managers once promoted.

Lessons for Firms and Managers

So why might be firms be doing this, especially since the Peter Principle is a widely known phenomenon among managers? We provide evidence that the Peter Principle may be the unfortunate consequence of firms doing their best to motivate their workforce. As has been pointed out by Baker et al. (1988) and by Milgrom and Roberts (1992), promotions often serve dual roles within an organisation: they are used to assign the best person to the managerial role, but also to motivate workers to excel in their current roles. If firms promoted workers on the basis of managerial potential rather than current performance, employees may have fewer incentives to work as hard.

We also find evidence that firms appear aware of the trade-off between incentives and matching and have adopted methods of reducing their costs. First, organisations can reward high performers through incentive pay, avoiding the need to use promotions to different roles as an incentive. Indeed, we find that firms that rely more on incentive pay (commissions, bonuses, etc.), also rely less on sales performance in making promotion decisions. Second, we find that organisations place less weight on sales performance when promoting sales workers to managerial positions that entail leading larger teams. That is, when managers have more responsibility, firms appear less willing to compromise on their quality.

Our research suggests that companies are largely aware of the Peter Principle. Because workers value promotion above and beyond a simple increase in salary, firms may not want to rid themselves entirely of promotion-based incentives. However, strategies that decouple a worker’s current job performance from his or her future career potential can minimise the costs of the Peter Principle. For example, technical organisations, like Microsoft and IBM have long used split career ladders, allowing their engineers to advance as individual contributors or managers. These practices recognise workers for succeeding in one area without transferring them to another.

See original post for references

,

The interesting bit is that pretty much everyone knows about this, yet it still persists.

When, now almost a decade ago, I was doing my EMBA at LBS (out of curiosity more than anything else, for example I liked like one of the strategy professors kept referring to management consultants as pin-striped pigeons. EMBA is also imo way different from MBA, as pretty much everyone there had at least 10 years in the real world, unlike most MBAs who still live in sort of student version of reality), the people teaching org/leadership classes would repeatedly stress one thing – a good top manager skill set is entirely different than good skill set at other positions. And that most likely, what got you there will not be what you’ll need there.

This is especially true in engineering.

What makes a good engineer is very different from what makes a good manager.

A very good engineer can make a very bad manager, and a very bad engineer can make a very good manager.

Engineering firms ignore this completely.

The one’s I have worked for anyway.

I went freelance in the end, to stay on the technical side.

One related issue which I think is frequently overlooked (not least because it undermines a lot of assumptions about careers) is that many specialists simply don’t seek promotions as they simply don’t want to get involved in management. Of my four siblings, all involved in tech/engineering/construction or the medical field, every single one has either refused promotions or not gone for available roles for lifestyle reasons, and I don’t think we are particularly unusual – I’ve known plenty of engineers, architects and medical professionals who have settled for the top grade in the ‘hands on’ side of their work rather than seek higher paid management roles. Sometimes its because they simply prefer that type of work and sometimes its for family reasons (i.e. more reasonable hours, less travel, etc).

I’ve often thought that this itself creates a distortion as people who are ambitious for high level management jobs are not necessarily the best people for those jobs. One reason at least one person I know who refused a management promotion in construction did so said that his reason was that life was too short to spend 8 hours a day sitting in an office with a bunch of ambitious backstabbing *family blog*, he’d far prefer being out on construction sites.

Preach it, PlutoniumKun!

My mother was a teacher who refused to become an administrator. She didn’t want to get involved in management and she loathed meetings.

Her hatred of meetings was exceeded only by my father, who was an engineering research lab guy until well into his later years. What my father thought of management cannot be said here, as this is a family blog.

I was going to mention the issue in education, viewed as a parent, wife a teacher. The best teachers are so frequently “promoted” to administration, leaving inferior teachers at the child-side level. I do not have my own survey to verify, but I suspect that more than half make bad administrators at the individual school level, and then the more aggressive, not the most talented, seek and find promotion again to the district-wide admin.

My wife did her first two years teaching with a principal who had been an outstanding middle-school teacher, only to become an incompetent, suck-up, apple-polishing admin, who made her life miserable by setting up “performances” of her elementary music students for senior administrators in the district.

Hah, yes, I greatly prefer the content side of NC to the “business of the business” side of NC….and NC is teeny!

The flip side of that is that businesses often don’t provide career and advancement paths for those that want to stay in their specialist field and not get involved in management (either because they are bad at it, not interested, or whatever). Management is treated as the profession ‘at the top’ with the result that anyone who wants to advance beyond a certain point needs to do it or else see their career stagnate.

This is in contrast to volunteer/hobby organizations I’ve been involved in, where management is treated as a task just like any other and is fulfilled by those with the time and aptitude to do so. That’s not to say that good ones aren’t highly valued, but they are playing a role just like any other and are only one of many ingredients needed for success.

I’m not quite sure why this happens (it doesn’t always, but a lot of the time it does). It could be a combination of the human tendency to feel that your own contribution and field is the most important/valued/necessary for success, with the fact that managers are responsible for defining roles, rates of pay and the like. You can certainly see this in action with the MBA takeover in fields like healthcare and academia, and I wouldn’t be too surprised if this is just a pathological extension of a basic tendency.

Particularly bad in academia where there’s no split ladder and people tend to believe that they have transferable smarts rather than very specific skills.

Often senior leaders in large science projects are very good students.. with all the dysfunction that implies.

technical organisations, like Microsoft and IBM have long used split career ladders, allowing their engineers to advance as individual contributors or managers

I once worked for a company that did that. The tech specialists were known as “kings”: ‘he’s the xyz king’ was the sort of thing said. Then there was a change of management fashion and the kings were pushed into early retirement (on generous terms). They bided their time. Sure enough they were soon hired back as “consultants” (on remarkably remunerative terms).

How we all laughed.

The post’s reference to two-track career ladders at technical organizations, like Microsoft and IBM, seems quaint. Who is doing all that contracting of software design to India? I never worked for IBM but from what I could gather it has become a consulting firm not greatly different than the firm I worked for. Now, ‘xyz’-expert has become expert in applying software product ‘x’ and good luck when ‘x’ is replaced by ‘y’.

Eons ago, as a young civil servant, I remember going on management courses and being told “promotion is not a reward”. We were told never to ask ourselves how well somebody had performed at their current level, but how they were likely to perform at a higher one. I think this is till basically good guidance, even if most organisations these days, both public and private, have been devastated and function badly, if at all. One reason for that is that management itself has been devalued, and in many organisations now consists of little more than ticking boxes, going to meetings and giving reports. It’s unsurprising that many people don’t want to do it.

The example given here is a slight caricature, since the clear distinction of roles between salesmen and managers isn’t typical of the way most organisations function, where some management at least has to be done at every level. But in some ways the problem is worse in hierarchical organisations with different management levels: a person who can manage a team of five effectively may not be able to manage five teams of five just as well, and it’s there that the rally big mistakes tend to be made.

>how well somebody had performed at their current level, but how they were likely to perform at a higher one. (my bold obviously)

But didn’t that phrasing indicate a problem with the whole organization’s view? “We need somebody that can do X, Y, and a person who can manage those two projects”. Ok, but why is the manager considered a “higher” level? He/she’s useless without the other two, and maybe they don’t perform so well without her/him, sure, but why should this person be considered “promoted above them”?

The whole theory was that somebody who really “knows the work” can “lead” the lesser lights. However, this has not worked out well in practice. I don’t, as usual, know the answer. The cause is mostly the supposed need for suffocating paperwork, people have tried to address that but generally have failed. In any case regarding some people as “better” because they can somehow convince current management that they can also be managers (which is generally, like everything in life, an arbitrary grade given by people who mostly look for other people whose behaviors resemble their own) is a bit much.

PS: we do supposedly have a “Y” promotion graph here at work, where if you just want to be an tech guy you still can theoretically be at the same “level” as a division manager, pay-wise anyway. But the difference in ages and backgrounds given the “equal” levels is illuminating.

What makes it even worse is when people higher up the hierarchy can succeed without skills needed for lower levels in the hierarchy. Two of the best managers I’ve ever worked for were terrible as technicians and engineers; the Peter Principle would’ve never even applied to them, because they were promoted from positions of incompetence to competence.

Because we have an unbreakable hierarchy and status-based viewpoint of division of labor, the idea that the assignment of leadership shouldn’t just be based on perception of previous status is unthinkable. Some lowly 18-year old assembly line tech might, with a couple of years of training, be a top-tier CEO? lol, pull the other leg. Promote from the C-Suite or GTFO.

There’s an aversion in the private engineering field to paying technical experts for being technical experts. The better- to big money goes to project managers and “rain-makers”. The technical experts at some point rarely get raises unless they move to management, where they are both unhappy and not experts.

In the old communist block it was common that technical specialists had a higher salary than their bosses. Unfortunately, I suspect managers were often promoted more based on loyalty to the party than managements skills. All systems have their strengths and weaknesses.

The root cause of the Peter Principle is the idea that people higher up in the decision-making chain are inherently more valuable by dint of being higher up in the decision change. If you want to increase your societal worth, you HAVE to go up the chain. So who cares if you’re unworthy, to the perspective of our capitalist hierarchies a mediocre CEO is worth more than a brilliant mid-level manager. Even if you break down their worth in terms of revenue and marginal utility and opportunity costs, this viewpoint is unquestionable. And it’s reflected in terms of status and compensation.

Why do we make things this way? Capitalism (and, let’s be frank, every bureaucracy in a liberal democracy) is extremely hierarchical. The idea that a highly-performing sales rep or staff recruiter or floor technician should be compensated more than the C-suite is horrifying — not just from a compensation perspective, but from a perspective of upending social relations. How DARE a company deem a high-performing sales manager more worthy than an average CEO?

The Peter Principle is a fair tradeoff to avoid the horror of the contributions of a mid-level product manager appearing to be worth more than the CMO.

The sports analogy makes me think of a long-time conventional wisdom in baseball, that mediocre players make the best managers. Alex Cora, manager of the reigning World Series champion Red Sox, is a highly regarded coach but was a career .243 hitter, had exactly one season in which his wRC+ was above 100, and had a career 4 WAR. Likewise, Bruce Bochy, who led the Giants to the three even-year bull$&!# championships in the early teens, was a .239 career hitter with only a career 2.6 WAR.

Ted Williams, regarded as one of the best hitters of all time, had a largely sour career as a manager, outside of the ’69 Senators season. Manager win record of 42.9%, very antagonistic relationship with the merely average players on his teams. However, what may be the most enlightening on this was the reputation he had as a batting instructor. Despite being a historically great hitter, he was rather lousy as a batting instructor as he never was able to give good advice on how to improve the mechanics of one’s swing, as he never had to think about it himself; he swung, and he got hits.

Which may be applicable to the professional world, writ large. People who lack innate talent but have motivation will try to learn as much as they can about the mechanisms and systems of their field to make up for that lack of talent, which sets them up better for what a manager does. Whereas the naturally gifted can lean more on their intuition and instinct, which makes them great at what they do but poor at guiding others to improve their work.

A key bit of training for anyone in business is to get exposure to the notion that people think differently. While seemingly obvious, that is not acknowledged in practice as any number of anecdoters may opine. Experiential learning and other techniques have application in helping reach budding managers before they get too set in whatever ways they have.

Here are some examples from a learning institute that has done work with middle and upper management and with flag-rank military personnel.

Have all participants take a battery of tests and assessments such as Meyers-Briggs and others.

Then have them line up in order based on their scores for each attribute, such as Introvert (say, score of I-50) down through some balanced score and then into Extrovert (say, up to E-50 or whatever), N (Intuitive) to S (Sensing) and so on.

Repeat that for other assessments such as one for learning style (auditory, visual and sensory learners) as applicable.

Those may provide some concrete way for people to look at themselves and others in new light. How that may translate into subsequent behavior in the management or technical realm is a topic for subsequent lifelong learning. That also helps chip away at the middle management permafrost layer, which seems to take on a life of its own if allowed to fester.

I’ve taken the Meyers-Briggs many times in both the private and government sector, mostly to no avail (hardover INTP here every time). The military openly scoffed at its value, while the private sector pays it mere lip service for the most part. My experience in both realms has been that management strongly selects for extroverts and that strong introverts are pushed into niches where they’ll ideally blend into the woodwork and just be quiet.

Meyers-Briggs is nothing but pseudo science embraced by the business world.

If it has been adapted by the military, it explains a lot of what has happened over the past 18 years.

Yup, spot on. It’s a total scam.

The Capitalist Origins of the Myers-Briggs Personality Test

I agree that the widely expanded use of so-called psychological tools in evaluating all manner of job applicants is lucrative but a deadend. It is one more tool for the person or committee doing the hiring to hide behind when something goes wrong. The Lemming Principle is just as prevalent as the Peter Principle.

Managers are indeed filtered for certain behavior traits as they move up the chain of command. I suspect the most important criterion is that they behave just like the people doing the filtering.

The same generally applies in soccer. Most of the top rated managers, especially those who have had long careers were mediocre players or often not even professional footballers (such as Mourinho or Sarri of Chelsea). Of the current top 6 teams in the Premiership, two are managed by former top players (three if you count Pochettino, who had a pretty good career, but was not a big star), two by fairly modest lower division players (Klopp and Emery) and one by a non-player (Sarri).

Arguably the three greatest British Managers of all time, Jock Stein, Alex Ferguson and Bill Shankly, were all very modest footballers with fairly restricted careers.

Although I agree with you on this, there is at least one exception to this rule in English football history, and that is Brian Clough, who was a very good striker (until he broke his cruciate ligament) and then became an exceptional manager, taking a small regional club, Nottingham Forest, to two European titles.

My son was just telling me about Paul Davis, the MLB pitching coach (currently for the Seattle Mariners) who has no professional baseball playing experience, pitching or otherwise, whatsoever. It’s called pitching analytics—you don’t have to do it to teach it.

A lot of pitching is about knowing the best sequence of pitches. It’s one thing to have a 95+ mph 2-seam fastball along with a good change-up and a serviceable slider, it’s entirely another thing to know what order to throw those in when you’re pitching to a lefty who’s dangerous up in the zone but weak low and outside.

I think the Peter Principle is a false meme. It only happens in organizations that are somewhat meritocratic. Most organizations are not meritocratic, this has been true throughout history, and American culture has gotten less meritocratic since the book came out. If your organization simply doesn’t promote competent people, promoting people one or two positions above their competence level isn’t a problem.

I had always assumed the famed principle referred to Saint Peter, until I read the wiki entry just now.

The former interpretation just seemed to make sense, what with Peter sleeping, denying the Lord 3 times, cutting off the high priest’s servant’s ear, etc. A “Rock” also doesn’t need to do much, other than show up, and maybe guard the gate….

Reminds me of my days in the Air Force back in the 90’s. A colleague of mine (Shane Bolles where are you?) and I in aircraft maintenance had brainstormed/bitchfested this idea at great length, about how the Air Force systematically undervalued and/or promoted it’s best technicians “up and out” of their career field, resulting in far less than ideal capability to do what we were there for in the first place – to actually maintain and repair combat aircraft. Unlike me, he was a bit of an idealist and still believed in the system, so he actually followed through on the idea by submitting an Air Force suggestion form outlining the problem and a proposed solution in great detail.

His basic idea was to create a two track promotion system, similar to what the Army had several decades back (but rarely actually implemented), whereby an individual could be promoted through the traditional enlisted grades or choose to pursue a specialist promotion track. This would allow super performers to remain super performers while still getting the promotions they deserved and those so inclined and/or chosen to follow the traditional management promotional track. Needless to say, after receiving a perfunctory letter back thanking him for the submission, the idea went absolutely nowhere, but I had to give him much respect for submitting it.

A few short years later I “self-identified” out of the maintenance management career field and lucrative promotional track by volunteering for a commander’s staff position as a squadron budget analyst, committing “career suicide” in the process. But it opened up an entirely new area of interest and led to the job I’m doing now in the private sector, so it was time well spent in the end. As far as I know, the USAF continues to pursue their “generalist over specialist” philosophy to this day, one time pretensions to “Quality Air Force” principles notwithstanding.

As an ‘engineer’ (that is, a computer programmer) I was gradually forced into a managerial role, not only by hierarchical-culture and upper-management pressures, but by the fact that if I wanted to be able to work at all constructively, I had to do or at least influence some of the management going on. Management is actually an extremely difficult job compared to engineering etc., because one is dealing with human beings, instead of machines and other material objects whose behavior is semi-predictable and usually not deliberately hostile. We do not have reliable general theories for the behavior of humans, so the manager must work through intuition, instinct, political skills, charisma, luck, and the like. Some of these qualities, like artistic inspiration or love, come and go mysteriously. It’s a bit silly to attempt to quantify them, especially with low-dimensional integers.

There is also the emotional and sensual cost of sitting through meetings, which seem to be a necessary tool of management and yet are toxic beyond belief.

At the same time, the manager must have some understanding of the work being done under his or her supposed leadership, unless by some chance a knowledgeable, non-treacherous subordinate is available to explain everything every day. That is why in such arcane crafts as higher technology requires, promotions to a level of incompetence seem necessary.

I was fortunately able to turn the money tap off and slip out of the cage before it was too late. I can understand why so much money must be given to managers to keep them on the job — which, by the way, does seem to be a necessary one, at least given contemporary culture, relations, and practices.

This seems to be my sweet spot professionally. I’m too hands-on to want to be a manager full time, but I’ve done the job before and know how to wear either hat as needed. It can feel a bit like the Office Space ‘people skills’ sketch sometimes, but my managers seem to value it.

Pay has to be linked to promotion (above competence), otherwise how did top management justify it’s insane pay for often equal incompetence.

Today it’s not even necessary to have that window dressing, it’s just a fact that the incompetent are usually more willing to be corrupt that drives the game to have the morally corrupt inside the circle and those not outside.

The US Navy took Peter seriously. It makes promotion decisions by committee where all members review performance evaluations over time and try to pick candidates who are already manifesting competencies needed at the next rank. As a consequence, technical skill becomes increasingly less important than managerial and leadership skills. An additional consequence is that it drives out officers who are skilled technicians but lousy leaders. There is a price for everything.

My point is that the Navy is a crucible that demonstrates some less than desirable unintended consequences of implementing Peter’s notion. Trying to contrast the Peter Principle and systems designed to thwart it would not be a simple empirical test because you wind up comparing wedding cakes and hand grenades. Both will blow you up, but in very different ways.

Who wants to promote their top sales person with that B.Litt. to be their company’s chief accountant? Horses for courses.

People very good at one or two things, superb in fact, are not necessarily good at managing multiple departments with varying, sometimes contradictory functions. Sometimes they are, and upper managers are supposed to know the difference. That used to be called judgment.

Where technical qualification or expertise is not immediately relevant, as in the accounting example, the generalist with the B.Litt. or the engineering degree might be just the ticket.

The life insurance business is one of the places where the Peter Principle is alive and well, as I discovered when I went to work for a major company.

I started out working with the top salesman in our office, who had invited me to come work with him. After a few months he was promoted to Sales Manager. Bad idea. Not only did he hate the paperwork and responsibility for others, he ended up taking a cut in pay. It didn’t take more than a couple of months before he was back in the field and another agent was promoted who had the necessary skill set for management, but who had been a second-tier salesman.

While I was working for another life insurance company an agent was promoted to management who was a good salesman, but not one of the top three. He did quite well and was eventually promoted to an executive position at the home office.

Other than the money, how is a move into management a promotion? Why are managers paid so much more than much of the ‘help’?

This is prevalent in the education field. I’m a retired teacher of 35 years. Most of the poor teachers became administrators. In my district I would guess this happened about 75% of the time.