Sébastien Caquard ,Associate Professor in Geography, Concordia University, Annita Lucchesi, PhD student, University of Lethbridge, Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, Associate professor, Department of History, McGill University, Leah Temper, Research Associate, History and Classical Studies, McGill University and Thomas Mcgurk, Lecturer, Department of Geography, Planning and Environment, Concordia University. Originally published at The Conversation.

For Indigenous peoples across the Americas, urgent threats imposed by the industrial extraction of natural resources has characterized the 21st century. The expansion of industry has threatened Indigenous territories, cultures and sovereignty. These industries include: timber and pulp extraction, mining, oil and gas and hydroelectric development. As well, the extraction of human beings from their lands has real implications for the survival of communities.

The debate of territory is essential in these resource conflicts. Maps — and those who make and shape them — are central to the discussion of land rights, especially when it comes to industrial resource extraction and Indigenous peoples.

Our project, MappingBack, envisions mapping as a weapon and tactic to resist extractive industries. We see it as an excellent way to express complex Indigenous perspectives and relationships with the land.

Maps as Resistance

There is a long history of the use of maps and cartographic techniques by countries and governments to claim ownership over Indigenous territories. But since the 1990s, Indigenous communities have been deploying mapping tactics as a mode of Indigenous resistance, resurgence and education. These tactics use historical memory and ancestral knowledge to assert territorial rights and community visioning.

Indigenous communities have either led or collaborated with multiple players to launch a broad array of mapping projects as a way of reclaiming ownership on the multiple aspects of their territories. These projects range from low-tech community mapping approaches to the use of the latest online web mapping technologies.

Some academics have criticized these cartographic practices because of the continued subordination of Indigenous spatial world-views to western technologies and histories. It is time to revisit these dominant mapping representations and conventional processes so that we can present different conceptions of the world. Representing these different conceptions calls for supporting the development of Indigenous cartographic languages.

Indigenous peoples conceive the diverse range of Indigenous territories as spaces of living relations; they are homelands since the beginning of creation; they are the reserve lands of forced resettlement, or they are spaces of refuge away from the violence and pressures of settler societies.

MappingBack: A Virtual Community

In 2017, MappingBack organized a three-day workshop in Montréal that brought together 35 participants to collectively exchange ideas about mapping in Indigenous‐extractives conflicts. The discussion at the seminar helped to form the foundation of an online Indigenous mapping platform.

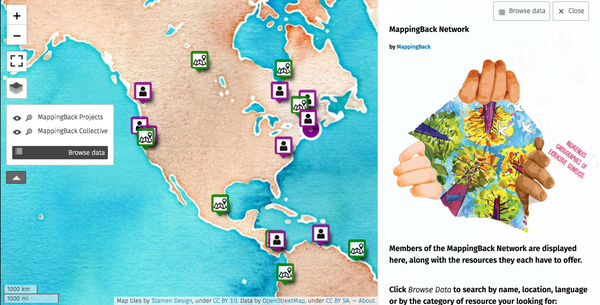

The MappingBack platform is a tool to resist the industrial extraction of natural resources on Indigenous territories. MappingBack project

The participants were members of Indigenous communities engaged with the representation of territory, cartographers interested in alternative forms of spatial expressions and researchers and practitioners with expertise on extractive industries.

These different players worked together to challenge and explore forms of cartographic expressions to represent multiple issues, perceptions, meanings, histories and emotions that are at stake when industrial extraction enters Indigenous territories.

Participants of the MappingBack workshop in Montréal, Oct. 15, 2017.

“Mappingback – Indigenous Cartographies of Extractive Industries,” grew into an online platform from those three days: it is a virtual collective space where Indigenous communities and allies can share their experiences and expertise related to mapping resource conflicts. Communities can also access experiences, stories and mapping tactics developed by others to fight against extractive industries on their homelands.

In developing MappingBack, we were inspired by the Guerilla Cartography’s collectively produced atlases. They aim to create a “new paradigm for cooperative and collaborative knowledge” to have a “transformative effect on the awareness and dissemination of spatial information.”

Powerful Collective Knowledge

The MappingBack platform helps to mobilize a broad range of alternative forms of spatial expression to serve the communities for public education and advocacy in defense of their territories.

We divided Mappingback into two main sections. Mapping Gallery showcases a selection of mapping examples and processes designed with and by Indigenous communities. It includes maps designed during the 2017 Montréal workshop like The Violation and Restoration Map as well as other examples crafted during the 2018 Indigenous Mapping Workshop. Each example includes written or oral reflections about the mapping process.

Whose Land is it Anyway? (crafted by Charlotte Adams, Kaitlin Kok, Melissa Castron, Tom McGurk, Mary Kate Craig, Sébastien Caquard – Aug. 2018)

Network, the second section of the platform, offers a list of resources available for communities interested in using spatial representations to fight against extractive industries.

The resources have been mapped with uMap, a free open source mapping application and include the names of Indigenous communities involved in fighting against extractive industries as well as a list of individuals indicating the expertise they are willing to contribute to the mapping project (Eg. GIS, legal, social or financial support).

Because some of the Indigenous communities involved in fighting against extractive industries have been exposed to high levels of threats and violence and have paid an expensive human cost, some of these resources will only be shared on a case by case scenario for privacy and security reasons.

MappingBack can support Indigenous perspectives on territories and resources through spatial representations. We hope it will serve Indigenous communities fighting against extractive industries. These fights are often at the forefront of broad and urgent environmental threats.

When I used to work for the city of Memphis, I made a map set for a city council person to use for town halls. This council person wasn’t that great or knowledgeable about her own district, but loved the map set. The maps covered up her flaws and made her look authoritative. All the other council members wanted a set for their district themselves. I saw how powerful maps were, but didn’t feel great about it. I volunteered making maps about other subjects for advocacy groups. Sexual assaults, foreclosures, etc. Nothing makes a map maker know he made a good map then when it pops up on the projector screen and a crowd gasps. It is almost like making art because you get an emotional response from the viewer.

As a lifelong map freak, I’ve almost always experienced them as art, and your description makes it easy to see how making them can feel likewise.

Good important stuff. The exciting part starts when you go into a poor community with the map and you begin to have people talk about the spaces depicted–where land was stolen, where critical foraging takes place (or once did). . . where the arable land is that people have been eyeing. Many tensions tend to lurk beneath the surface. In 2008 a Grenada community I have worked in mapped some former estate lands that they had been squatting/working that were slated for sale to a new tourism venture. They designated some land for the new installation, then set about better dividing the lands among them–according to the kind of planting they did–diversified their production to make the case that they were feeding local people, and upped everyone’s production. The Canadian firm that was pacting with local pols to bring off the deal thought better of it.

In Asia IPs have long used maps to underpin their legal and regulatory claims on natural resources.

But they have their own “misleadership class”, so all that generally happens is that they start showing up in shiny new Land Cruisers. Maybe a school or two gets rebuilt, or a community hall or mosque. In terms of other concrete material benefits to the local people though, not a heck of a lot. The mainly Chinese EPCs use Chinese trades who come in on tourist visas, or else lowlanders for pretty much everything but security and some ditch digging. Training up local tribals is harder than it sounds, and keeping them once trained is even harder.

So all the locals really get in the end is use of the access roads and infra, which basically aids in their ongoing despoilment of the surrounding wilderness (here too the money from illegal logging etc. goes to the leaders not the ordinary folks).

Bottom line: for the most part these tools aren’t really saving the planet, they’re abetting crass shakedowns by warlords.

“A lotta people won’t get no justice tonight…”