By Chloé Michel, Portfolio Manager, Swiss Re, Michelle Sovinsky, Professor of Economics, University of Mannheim, Eugenio Proto Professor, University of Bristol, and Andrew Oswald, Professor of Economics, Warwick University. Originally published at VoxEU

Although the negative impact of conspicuous consumption has been discussed for more than a century, the link between advertising and individual is not well understood. This column uses longitudinal data for 27 countries in Europe linking change in life satisfaction to variation in advertising spend. The results show a large negative correlation that cannot be attributed to the business cycle or individual characteristics.

Advertising is ubiquitous. In recent decades, the volume of advertising has been growing dramatically. Therefore, it is natural to ask if this harms our wellbeing.

We do not perfectly understand the link between advertising and individual wellbeing. It is reasonable to assume that it might operate through two broad channels that have opposing effects:

- Positive: advertising informs. It may promote human welfare by allowing people to make better choices about products.

- Negative: advertising stimulates desires that are not feasible. This creates dissatisfaction. Hence, advertising might reduce welfare by unduly raising consumption aspirations.

At the national level, we do not know which of the two effects is dominant. Many national variables influence wellbeing, in particular the generosity of the welfare state and variables such as unemployment (DiTella et al. 2001, DiTella et al. 2003, and Radcliff 2013). But recent research on subjective wellbeing, described in sources such as Easterlin (2003), Oswald (1997), Layard (2005) and Clark (2018), has paid little attention to the role of advertising, and so there are no cross-country econometric studies of the effect of advertising using representative samples of adults.

Keeping up with the Joneses

In this context, is a reasonable hypothesis that advertising has a negative effect on wellbeing. Easterlin (1974) found early evidence suggesting that society does not become happier as it grows richer. He suggested that one mechanism might be that individuals compare themselves with their neighbours. Easterlin’s thesis, in part, assumes that we desire conspicuous consumption (Veblen 1899, 1904).

If individuals have ‘relativistic’ preferences, so that they look at others before deciding how satisfied they feel, then when they consume more goods, they fail to become happier because they see others also consuming more. The pleasure of my new car is taken away if Ms Jones, in the parking spot next to mine, has also just bought one. More recent evidence on ‘comparison effects’ has been reviewed by Clark (2018). Mujcic and Oswald (2018) also find longitudinal evidence of negative wellbeing consequences based on envy.

Since Veblen, many researchers have worried about negative effects on wellbeing of advertising. In some cases they have found small-scale evidence (examples include Richins 1995, Easterlin and Crimmins 1991, Bagwell and Bernheim 1996, Sirgy et al. 1998, Dittmar et al. 2014, Frey et al. 2007, and Harris et al. 2009). Research has focused on the likely detrimental effects upon children (Andreyeva et al. 2011, Borzekowski and Robinson 2001, Buijzen and Valkenburg 2003a, Opree et al. 2013, and Buijzen and Valkenburg 2003b), although the most recent work, by Opree et al. (2016), produced inconclusive results.

Evidence of a Negative Effect

We have found evidence of negative links between national advertising and national wellbeing (Michel et al. 2019). Using longitudinal information on countries, from pooled cross-sectional surveys, we find that rises and falls in advertising are followed, a few years later, by falls and rises in national life-satisfaction, giving an inverse connection between advertising levels and the later wellbeing levels of nations.

We took a sample of slightly over 900,000 randomly sampled European citizens in 27 countries, surveyed annually from 1980 to 2011. Respondents reported their level of life satisfaction and many other aspects of themselves and their lives. We also recorded total advertising expenditure levels.

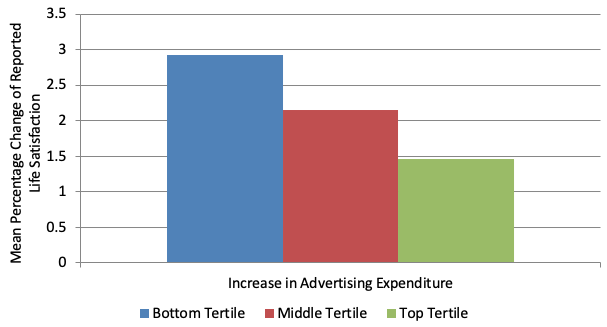

Figure 1 illustrates the study’s key idea. It divides the data into tertiles and then plots the (uncorrected) relationship between the change in advertising and the change in life satisfaction. The three vertical bars separate the data into countries that had particularly large increases in advertising expenditure, moderate increases, and small increases. Figure 1 shows that the greater the rise in advertising within a nation, the smaller the later improvement in life satisfaction.

Figure 1 The inverse longitudinal relationship between changes in advertising and changes in the life satisfaction of countries, 1980 to 2011

Notes: Based on a sample of approximately 1 million individuals. Based on shorter period if data not available for that country. Bottom Tertile consists of Czech Republic, Germany after 1989, Estonia, Finland, Lithuania, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia. Mean change 2.93. Middle Tertile consists of Bulgaria, Western Germany (before 1989), Denmark, UK, Sweden, Slovenia, Netherlands, Turkey, Spain. Mean Change: 2.15. Top tertile consists of Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Croatia, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Portugal. Mean change 1.46.

Advertising does not have a spurious association with life satisfaction that is attributable merely to the business cycle. Using standard regression analysis, we were able to show that the negative effect of advertisement on life satisfaction is not due to the correlation of both variables with the GDP. This negative effect is robust to the inclusion of other variables like country and year fixed effects, unemployment, and individual socioeconomic characteristics that are typically included in any happiness equation.

The effect implies that a hypothetical doubling of advertising expenditure would result in a 3% drop in life satisfaction. That is approximately one half the absolute size of the marriage effect on life satisfaction, or approximately one quarter of the absolute size of the effect of being unemployed.

These results are consistent with concerns that were first more than a century ago, and regularly since (Veblen 1904 and Robinson 1933, for example). They are consistent with Easterlin (1974, 2003) and Layard (1980). They may also be consistent with ideas about the negative consequences of materialism (Sirgy et al. 2012, Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002, Speck and Roy 2008, and Snyder and Debono 1985).

Although there is evidence of an inverse longitudinal relationship between national advertising and national dissatisfaction, we still need to uncover the causal mechanism. But this demands investigation, because the size of the estimated effect here is both substantial and statistically well-determined.

See original post for references

Thorstein Bunde Veblen abides.

At times, it seems like advertising is the only growth industry in the USA (see: Facebook, Google, et al). You have to make a conscious effort to ignore, or at least filter it so that services or products that really fill a need for you make it through the screen. Start with ‘display’ ads on websites; I can’t remember the last time I clicked on one.

I’ve read discussion of whether or not the market is in a tech bubble again, but I wonder if it should be looked as an advertising / marketing bubble. If that is the case, I’d imagine the companies that will survive the pop will be the ones whose info has value as surveillance for intelligence agencies.

This is one possible explanation already for why USA seems reluctant to move against allegedly monopole-like situations both Google and Facebook are in. Of course additional considerations include the fact that almost infinitely upscalable information services tend to be some sort of natural monopolies. Competition doesn’t really make sense for customer with seemingly free service like Facebook, and G+ is dead. Similar situations exist with many other social network services.

This is kind of a wide open question. There are so many variables to consider. Just to focus on the actual advertisement might be helpful. Positive, negative and maybe also frivolous. Maybe there should be at least three categories. The only one that isn’t offensive is positive advertising. Maybe someone should do controlled studies on the effects of positive v. negative v. frivolous (deceptive) persuasion techniques. Again. And then compare these results to national dissatisfaction statistics based on political-economics. I, for one, appreciate being able to go on-line and find a very suitable item – just what I need – with all the specs for my examination; and then delivery is included. On-line nobody is haranguing me with an intrusive ad interrupting my favorite mystery show; nobody is cold-calling me – the ultimate act of rudeness – pretending to be offering me a deal. And maybe there is a way for research to separate out being “dissatisfied” and being annoyed. What exactly is dissatisfied?

I fully agree. The “positive” and “negative” categories in the article do not resonate with me. It’s something else. Advertising in almost all its forms just irritates the heck out of me. It drives me up the wall.

There is no escape. Newspapers, magazines, billboards, buses, trams, trains, television, phone, computer, radio, sports events, spam in all its forms, the list is endless. I have cancelled my satellite subscription because I felt I spent more time avoiding commercials than watching programs. I run ad-blockers on my computers and phones. I installed a private PBX to block cold callers and telemarketers. I have an RDS car radio that interrupts my music for traffic information, I no longer listen to radio stations.

And it gets worse. If I want to buy something on Amazon I have to shove more and more advertisements aside. I have to pay extra for an e-reader without commercials on it. And now car manufacturers even threaten to put advertisements on modern car’s LCD screens. The horror!

I can surely imagine that people’s well-being is negatively affected by advertising. Not, as the article states, because “advertising stimulates desires that are not feasible”. Rather, simply because being bombarded 24/7 with unwanted, often untrue or exaggerated and rarely useful messages wherever you look or go is a merciless attack on peoples peace of mind.

Occam’s Razor: the less assumptions you have to make, the more likely the explanation. And to me, it seems the most likely that people simply more and more despise advertising in all its forms. And being surrounded every day by things you despise is not positive for your well-being.

I fully agree with you. The question of whether advertising meets or manufactures need is irrelevant. Advertising itself is pollution. Its mere presence is harmful to quality of life, and its sheer ubiquitousness renders it a noxious weed.

European advertising? Man that hardly even counts, that’s like testing alcoholism with 3.2 beer.

Come across the pond, guys, we’ll give you something to gawk at.

Charlie Brooker (Black Mirror) had his finger on this pulse years ago.

“How (aspirational) TV ruined your life”

https://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=charlie+booker+aspiration

and decades before Charlie was https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vance_Packard

and of course before that Veblen mentioned above

I stopped watching TV because of the ads and also stopped reading magazines. I consider ads to be a negative, I seldom find myself informed by ads.

Ads purpose is to make oneself feel back and then the item advertised will solve all ones problems.

Sometimes I watch TV just to see what the ads are selling now: fear? anger? shame? guilt? (If you, the viewer, do not buy this product then you will be cast out, shunned by society, and your children will suffer.) That seem like the subtext of a lot of the ‘keeping up with the Jones’ ads these days, imo, now that we’re a hyper-competitive society with no second chances. (Once upon a time the US was the land of second chances.)

Advertising now is a lot more vicious (with a smiley face) than it was 30 years ago, imo. Maybe that’s because the once great middle class, engine of the purchasing power capitalists relied on, is now so reduced that advertisers have to hit viewers with a hammer to get them to buy stuff.

Heck, even political campaigns are getting in on the act, with the last Dem pres candidate calling her opponents supporters ‘deplorable’ (outcasts ) and the GOP pres candidate calling his opponents ‘losers’ (outcasts). My 2 cents.

Likewise in terms of the goggle box, but perhaps they should be talking about marketing, as advertising serves a purpose IMO, as in ” Gate for sale, 5 years old & in good condition , 6′ x 3′, £100 ono. If I happen to be looking for such a gate, then I can investigate further.

The problem for me is when the above gate or any other item that is being sold, is transformed through marketing spiel into something that will allegedly change your life like – buy this car & you will soon be having sex with supermodels or driving at 200 mph on a totally open road. Ads aimed at kids I imagine are a problem for hard pressed families & their kids who do not get the new in thing, are likely to suffer from their supposedly more fortunate peers.

I also suppose that in a situation in which austerity measures, no rise in real wages, indebtedness & crappy insecure jobs, for an ever increasing amount of people these things that are constantly being flaunted at them just become evermore unattainable, which is not likely to cheer them up very much.

I agree with Bill Hicks on marketing, which IMO is just a fancy word for lying & has gradually pervaded just about everything.

I lived in Paris in the mid 70’s and boy was TV (very few ads) a pleasure compared to the US version. I think there is also a direct correlation between the amount of ads and the quality of the actual programs. Ad burdened TV tends toward infantile, simplistic programs with well defined good and bad guys. Ad absent TV tends toward richer plots, less biased news, better music, perhaps less variety but compensated for by much richer content. Well, that’s what watching TV in France 1975-1980 led me to conclude. There is some evidence (to me) that American TV programs were also richer and of higher general quality in the 1950’s before advertising really took off in the ’60’s. Of course there were always exceptions.

This kind of does make sense on superficial level: The more ads you are bombarded with increases the information inflow to the viewer. This should make following of the plot more challenging, assuming there is anything even vaguely interesting among the ads unless the viewer skips the ads completely.

It’s like distractions and disruptions when trying to work on something very challenging, it’s hard to keep focus if one is bombarded with other irrelevant stimuli all the time.

I’m so sick of it I only watch streaming where there is 0 ads and 0 regular TV anymore, nor the radio.

We cancelled cable a couple years ago, so now when I watch regular television (for sports, occasionally) the amount and intensity of the ads is unbearable. They try to convince me to take pharmaceuticals for maladies I never knew existed, to feel that everything I own is inadequate, and that I’m too fat. Then the next block of ads will work to sell me alcohol, sugar, and financial services for all the money I don’t have.

I’m convinced that advertising is a form of national self-abuse akin to mental pollution.

That’s a pretty solid study. Sample size 900,000, polled annually over 30 years.

I would love to see some attempt by policymakers to quantify the impact and hold advertisers accountable via a targeted tax, but I’m not holding my breath. (The EU is probably the best chance if it’s going to happen at all).

For years I have questioned whether advertising is effective. Does it really pay for itself in more sales revenue?

I breeze past almost every ad I see on the internet (if I can get away with it). Still, I suppose I must be grateful to the advertisers, otherwise a lot of media that I follow would simply disappear. That’s why I tolerate several ads a day on the New York Times, urging me to enroll in a graduate program at NYU (I’m in my mid-seventies).

Herbert Hyman developed the idea of “reference groups” in the 1950s to explain this phenomenon. It’s a bit different from “conspicuous consumption,” in that the issue is not a desire to consume more things than others, but a desire to consume social recognition sufficient to make a person feel respect. Things, it turns out, are not always sufficient to bring respect. (Just ask Donald Trump.) The values of the groups one wants respect from are more important than ordinary things.

The best analysis I’ve ever read on advertising was Michael Schudson’s ‘Advertising as Capitalist Realism’, which unfortunately I cannot find in full online, but it highlighted the parallels between the goals of Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union and advertising in the west. If memory serves, he came up with various reasons advertising was more successful as an art form than Socialist Realism was.

Pdf

In relation to climate change, the sustainable and concious consumption should be made into cool status symbols instead of conspicuous consumption. Probably best way to drive this in is to target Women, because due to sexual status effects they can influence males far better than other males.

Now I’m moving into Command & Control territory so ‘Liberals’ beware, but in order to make above happen we need to ban all the tv-shows, magazines and similar glorifying ‘high life’, rich people and celebrities. This would probably increase life satisfaction in general, because these are also kind of manifestations of conspicuous consumption.