Yves here. Earlier this week, reader chuck roast asked about how to break the public pension fund addiction to alternative investments, which given how much money has been pouring into these high-fee, high risk strategies, are just about certain to underperform. We’ve pointed out for years how private equity has failed for the prior ten years to earn enough to justify its higher risks. Ludovic Phalippou of Oxford reached an even more damning conclusion, that private equity funds on average have not even outperformed the S&P 500 since 2006

So it seemed timely to discuss other, sounder approaches to the desperate reaching for returns.

In the world of public pension reform, there are agitators for a 401(k) or hybrid plan solution (Pew, Laura and John Arnold Foundation, Reason Foundation, ALEC, etc.), public employee/retiree organizations (which largely advocate for increased funding), and academics (which explore best solutions and legal impediments, yet steer clear of advocating innovation or orchestrating transitions).

One small non-profit, Pro Bono Public Pensions, seeks to fill the innovation and orchestration void and create fair, secure and sustainable solutions. The Founder and President is Gordon Hamlin, who got started in the field when he (and 44,000 others) signed up for Josh Rauh’s MOOC on the Finance of Retirement and Pensions. Gordon was one of a handful of students selected to participate in the final forumat the Stanford Graduate School of Business, based upon his team’s proposed constitutional amendment and Vanguard-type indexing of the Mississippi PERS portfolio. In 2016 he was a Fellow in Harvard’s Advanced Leadership Initiative.

Gordon first came to my attention when he sent details of an indexing proposal for South Carolina, which had become the poster child for rash investing in alternatives and admittedly had among the worst 10-year performance of any state public pension plan.

Gordon and several collaborators have published a comprehensive suggestionon how to transition to a new shared risk model (think New Brunswick, the Netherlands, etc.) through prepackaged Chapter 9 Plans of Debt Adjustment. Prepackaged bankruptcy reorganizations are commonplace in the corporate world, and there is no impediment to borrowing that concept for Chapter 9.

Gordon has submitted proposals to municipalities like Dallas and Birmingham, various states, and several local governments in California. Since last fall, he has consulted with a Pension Liabilities Task Forcein Connecticut. For the last 2 years, he has been working with some allies in Kentucky, writing Op-Eds and appearing on KET. The following article describes recent developments in Kentucky and proposes a specific legislative fix.

By W. Gordon Hamlin, Jr., President, Pro Bono Public Pensions. Please contact him at gordonhamlin@comcast.net

No specialized knowledge of public pensions is necessary to conclude that on March 28 the Kentucky General Assembly took the country’s worst-funded public pension plan out back and tried to put it out of its misery. House Bill 358 pounded nails in the coffin, leaving only one nail left—the Governor’s signature. On the last possible day, Governor Matt Bevin vetoedthe bill, citing a moral and legal imperative to protect benefits earned by public sector employees, and announced he would call a Special Session before July 1, thus creating even more chaos for the Commonwealth. The Senate President claimed he was “disappointed” and “perplexed” by the veto, with the Speaker of the House saying the House had “spent exhaustive amounts of time” developing the bill.

Here’s how one manager interpreted the bill’s impact on his mental health services organization, a “quasi-governmental employer” which participates in Kentucky Employees Retirement System Non-Hazardous (KERS-NH):

Pension Update: So I’ve spent all morning running rudimentary numbers for our company regarding the new pension bill. Here is what it amounts to for any of you who can share to the Governor’s office or other legislators: We’re a private non-profit Quasi. We have paid EVERY DIME ever required by KERS and have over 100 Tier 1 and 2’s active and over 200 retired. For the past several weeks we have met with numerous legislators and tried to explain to them how the bill as written will bankrupt most Quasi’s EITHER option they choose. Well here are our preliminary numbers. In order to Opt to stay IN the system we will be required to pay over $84,000,000 over the next 20 years. This is on a company with a current annual payroll of just over 6 million dollars. In order to Opt OUT of the system we would have to pay over $100,000,000 for the same period. (Someone can maybe help me with how this part was supposed to ‘save’ the Quasi’s).

This guest blog will (1) explore how Kentucky got to this point, (2) discuss some of the current fallout in bankruptcy and litigation, (3) analyze more specifically how HB 358 would have made matters worse, (4) examine an alternative merger plan which the legislature passed up, and (5) ask whether there is a path forward.

How Kentucky Got to This Point

The KERS-NH plan covers over 120,000 employees and retirees, with approximately 80% as direct state employees or retirees and the remaining 20% associated with seven regional universities or quasi-governmental employers (such as district health offices, regional mental health facilities, or rape crisis centers). As of June 30, 2018, KERS-NH admitted that it was only 13% funded, with assets of $2 billion and liabilities of $15.675 billion (computed with a 5.5% discount rate). The Solvency Test in the CAFR asserts that the assets covered 100% of active member contributions, but only 9.4% of the retiree liabilities and 0% of the active member liabilities. For all practical purposes, this plan is already in pay-as-you-go territory.

Several different studies have reached similar conclusions about how KERS-NH slid from over 100% funded status in 2000 to 13% in 2018. First, plan fiduciaries used an assumed 8.25% rate of return for years, thereby creating misleadingly low liabilities. When the Global Financial Crisis approached, the fiduciaries reduced the assumed rate of return to 7.75%. More recently, the assumptions were reduced to 5.5% as funding deteriorated and liquidity needs escalated. Second, the high discount rate and other actuarial assumptions created normal costs that were too low. Third, the General Assembly granted unfunded benefit enhancements, such as COLA’s. Fourth, the Dot-Com Crash and the Global Financial Crisis produced enormous negative returns.

But that wasn’t the entire story. Poor governance, leading to poor investment performance, has been amply documented in the book Kentucky Fried Pensions(written by Chris Tobe, a former Board member) and in last fall’s Frontline special, “The Pension Gamble”. John Farris, a former Board Chair, was quoted in the Frontline special: “I think that the pension board that was put together between 2008 and 2016 was probably the dumbest of money.” Other Board members basically admitted that they did not understand much of what they were expected to vote upon.

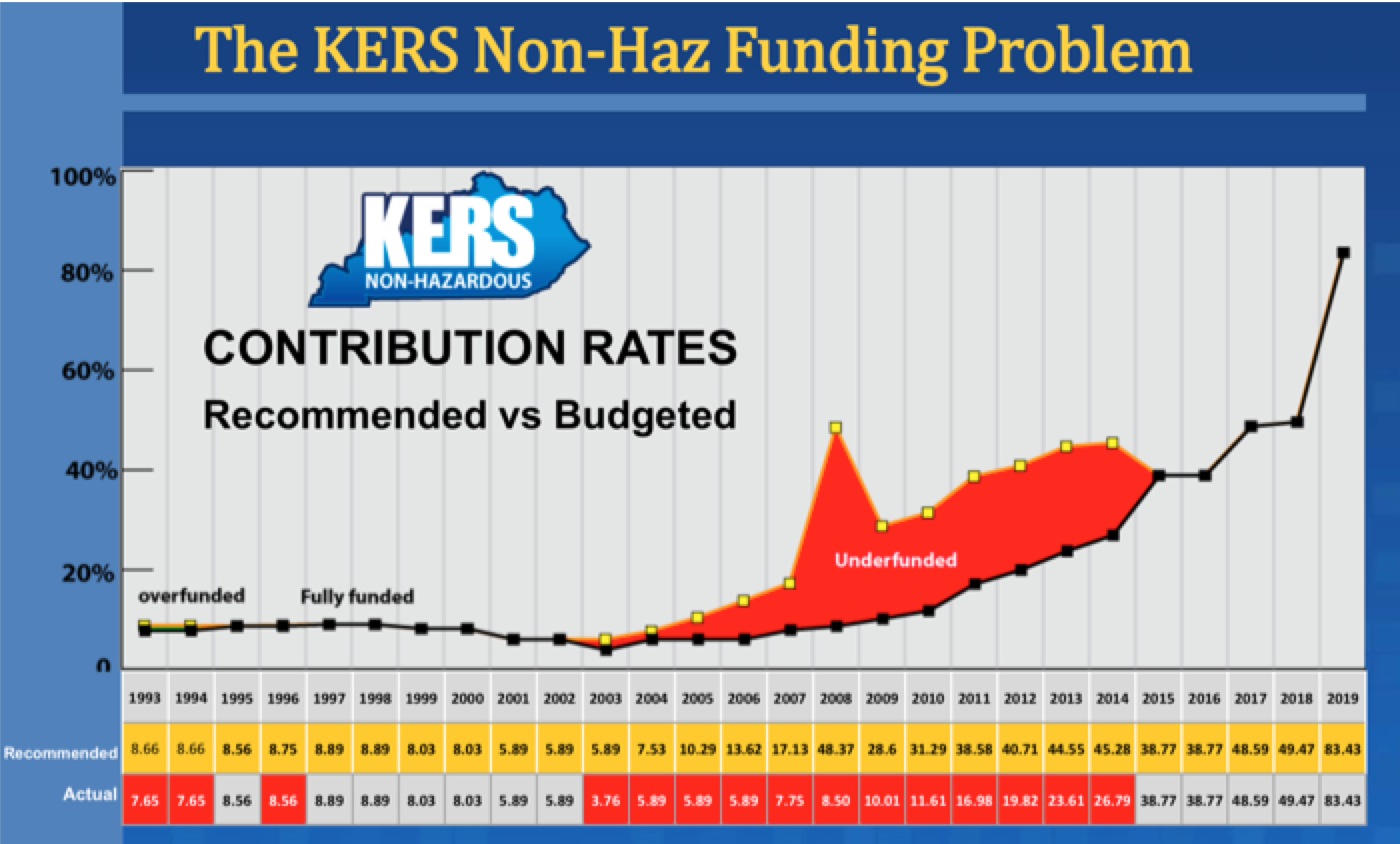

But, just as the Board collectively failed in its responsibilities, the General Assembly failed on an epic scale. From 2000-2014, budgeted contributions barely exceeded 30% of the ARC (which itself was always misleadingly low because of the discount rate, high inflation assumptions, unrealistic payroll growth assumptions, and the like). Once the General Assembly established the contribution rate, it applied across the board, even though the regional universities and other entities may have been able to pay more. Here is the history of underfunding:

Bankruptcy and Litigation Fallout

In 2013, Seven Counties Services, a regional mental health services provider in Kentucky and an employer allowed to participate in KERS-NH, filed for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 11, threatening services provided to some 32,000 Kentuckians. The Bankruptcy Court concluded that Seven Counties was eligible to file under Chapter 11, and the Sixth Circuit affirmed on appeal, but certified a question of state law to the Kentucky Supreme Court, where the case now sits. In the meantime, Seven Counties affiliated with another mental health services provider, Centerstone, and KERS-NH has continued to pay pensions to the retirees of Seven Counties. In effect, Seven Counties dumped its obligation to fund pensions into the lap of KERS-NH, just as corporations have dumped their pensions into the PBGC.

In late 2017, a lawsuit styled Mayberry v. KKR was filed in Franklin County Superior Court against KKR, Blackstone, Cavanaugh MacDonald (the actuaries for KERS-NH), Ice Miller (the law firm for KERS-NH), and numerous other parties, alleging breaches of fiduciary duties, fraud, and other torts under Kentucky law. At this point, the best that can be said is that the outcome is uncertain.

The fallout has multiplied even more in recent days, with Blackstone Alternative Asset Management and Prisma Capital Partners filing suit in Delaware Chancery Courtagainst Kentucky Retirement Systems and its board, alleging breach of contract and representations.[1]

In another case, the Franklin County Superior Court recently ruled that the Governor wrongfully failed to produce an actuarial report, which concluded that his proposed changes to the public pension system would actually make the funded status worse.

Without a global solution to Kentucky’s pension problems, the beat will just go on (with apologies to Sonny and Cher).

Under any reasonable analysis, KERS-NH has really been two pension plans—one whose funding has depended on the General Assembly and one whose employers got large portions of their funding independent of the General Assembly and have faithfully paid their contributions, year after year, for decades. Thus, while the General Assembly regularly shirked its obligation to make the annual required contributions on behalf of 80% of KERS-NH members, the other employers—the regional universities, district health departments, mental health organizations and rape crisis centers—stood ready, willing and able to make their ARC payments. But when the General Assembly decided not to pay on behalf of the 80%, it also decreed that employers of the 20% would not pay the full requested ARC.

During the recent legislative session, the Public Pensions Working Group (comprised of Senators and Representatives from both parties) held regular hearings and was charged with developing some solutions to Kentucky’s public pension crisis. The regional universities worked with a group of Representatives to develop the first version of HB 358. As presented, the bill froze contribution rates for one year for the universities at 49.47% for pensions and insurance contributions andallowed the universities to exit KERS-NH and pay off their liabilities over a 25-year period. Individual employees could elect to remain in KERS-NH, a provision necessary to comply with the “inviolable contract” public employees have with respect to their pensions under Kentucky statutes and state constitution. See KRS 61.692(1) (“in consideration of the contributions by the members and in further consideration of benefits received by the state from the member’s employment, KRS 61.510 to 61.705 shall constitute an inviolable contract of the Commonwealth, and the benefits provided therein shall not be subject to reduction or impairment by alteration, amendment, or repeal. . ..”).

Although the bill also specified that an actuarial analysis would be performed prior to any exiting decision, it was possible to perform some back-of-the-envelope calculations and conclude that the universities might be locked into a requirement to pay as much as 66% of payroll for 25 years into KERS-NH. Such contribution levels would surely have driven up tuition and made the universities uncompetitive across a several-state region.

The Senate then countered with revisions that allowed the quasi-governmental entities to exit the pension plan, but with little consideration of the rights of current employees. The Governor indicated he would sign the Senate version.

When the House and Senate could not agree on a single bill during the regular session, exactly one day—March 28—was left. The General Assembly reconvened, appointed a conference committee, and late in the day a new bill emerged.

The final version of HB 358 began with the premise that all regional universities and quasi-governmental employers would have been booted out of KERS-NH as of June 30, 2020, unless they affirmatively elected to remain. If they had elected to remain, then they would have paid 49.47% of the 5-year average payroll for the year ending June 30, 2020. The actuaries would have computed a full actuarial cost for all employees and retirees who were last employed by that employer, and the employer’s cost would increase by 1.5% annually until the costs were paid off. The actuaries would have used the lower of the KERS-NH discount rate or the 30-year U.S. Treasury rate prevailing on June 30, 2020, but in no event less than 3%. With the 30-year Treasury currently floating around 2.8%, it seems rational to conclude that a 3% discount rate might well have come into play, again creating a dual pension system, but this time calculating liabilities for the 20% based upon a substantially lower discount rate than for the 80%.

But there’s more! HB 358 gave employees of the regional universities and the quasi-governmental employers the option to remain in KERS-NH, in which case their employers would have remained responsible to pay the greatly increased costs for those employees. However, if (and this is a big if for both employer and employee) the employer failed to pay the monthly required contributions, then pension payments would cease. Governor Bevin highlighted this issue in his veto message, calling it “uncharted territory” and one that might not even be legal.

In other words, an employer electing to remain in KERS-NH may never pay its liability off. Indeed, the actuaries believed that the unfunded liability would actually be higher in 30 years. If the employer stayed out, then it would still have to pay for its retirees and any employees who elected to remain in KERS-NH. This was another concern of the Governor’s.

The actuarial analysis estimates a negative impact of $799 million, with $121 million attributable to the one-year continuation of the contribution rate freeze for the universities and quasi-governmental employers and $678 million attributable to the cessation provisions. The General Assembly would have been faced with higher contribution rates for the 80% of the members it is responsible for funding.

In short, the regional universities and quasi-governmental entities would have faced impossible payroll costs, whether they remained or whether they exited. Their employees and retirees would have faced an extreme forfeiture if the employer failed or ceased to make the monthly payments for some other reason. Governor Bevin called this result “unacceptable.” The General Assembly would face increased contribution rates for all its employees.

Overall, HB 358 was unfair, insecure and unsustainable. It was no solution at all. Everybody would lose.

Was There Any Alternative?

The simple fact that KERS-NH is for all practical purposes already on a pay-as-you-go basis ought to prompt thinking about alternatives.

For example, Kentucky might consider merging the regional universities and quasi-governmental entities, their employees, retirees and assets with the County Employees Retirement System (CERS). That system is much better funded than KERS-NH, and employers in that system include cities, as well as counties. The local health departments, mental health centers, rape crisis centers and regional universities may well have greater affinities with their cities and counties than with the Commonwealth. Nevertheless, this solution would still leave 80% of KERS-NH on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Thinking even more broadly, why not just merge all of Kentucky’s public pension plans, like Wisconsin did over 40 years ago? The Legislative plan is the best-funded of all, making it a convenient talking point for employees of all the other systems, asking “why isn’t our plan funded like the Legislative plan, which is for part-time workers?”

Then, if merging plans is worthy of a thought experiment, what else should be attempted as part of a major merger? One answer from ideologues might be to transition everyone into a 401(k) environment, but the “inviolable contract” under Kentucky law stands in the way of any such effort, not to mention the near-uniform opposition of all public employees and retirees.

There remains one lawful means to transition at least the local Kentucky public employees and retirees into a different environment. That is under Chapters 9 and 11 of the Bankruptcy Act.

Kentucky has already authorized a large array of local governments and special purpose governmental entities to file a Plan of Debt Adjustment under Chapter 9. Any “municipality” filing under Chapter 9 must certify that it has either reached agreement with the impacted creditors (in this case, the employees, inactive employees and retirees) on a plan or that it has attempted to reach agreement and failed.

Given this requirement, it’s easy to see that presenting a group of employees and retirees with a plan to transition them to a 401(k) environment would not meet with many takers. But, what about a shared risk plan along the lines of the New Brunswick Public Service Shared Risk Planor the Wisconsin Retirement Systems or some church plans (like the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)) or the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.)?

Given the low level of trust between the General Assembly and the pension fund members, is there some alternative to lobbing the problem back to the General Assembly to solve?

One answer just might be the same approach New Brunswick tried—create a Task Force of expert consultants and stakeholders to work with the actuaries to design a plan and then develop the legislation.

In short, the Kentucky General Assembly could have frozen contribution rates in KERS-NH for a year, created a Task Force of stakeholders, authorized funding for an independent actuary, and charged the Task Force to produce a reform plan.

In addition, the Task Force might propose any appropriate constitutional amendments, such as prohibitions on contribution holidays or unfunded benefit enhancements. A more fulsome analysis of this idea can be found here.

What Can Be Done Now?

Although the General Assembly tried mightily to create an exit ramp for the regional universities and quasi-governmental employers, neither math nor law will permit any similar solution. The cost of exiting and the cost of remaining will be impossibly high. The “inviolable contract” will prohibit the dumping of current employees. The moral and legal imperative of protecting retirees’ earned benefits, as the Governor has indicated, means that someone must pay, whether through a well-funded pension plan or on a pay-as-you-go basis.

Although some of the local health departments may be on the edge of insolvency, it seems unlikely that many would be “insolvent” and eligible to file a Plan of Debt Adjustment under Chapter 9 in the immediate future. Other entities, such as the regional universities, are considered organs of the Commonwealth and are not the special purpose governmental entities authorized to utilize Chapter 9 under Kentucky law. Still others, such as the mental health organizations, would have to utilize Chapter 11 (like Seven Counties Services did).

In other words, at this point, without a coordinated and comprehensive plan in hand or being developed, using bankruptcy to restructure seems problematic, at best.

On the other hand, what if the Governor could be persuaded that it just might make sense to merge all the public pension plans and transition into a shared risk model through maximum use of Chapter 9 and then use some carrots for the direct Commonwealth employees? That might not satisfy ideologues who want to push public employees into a 401(k) environment, but it just might prove to be a global compromise that would allow Kentucky some breathing space for its budgets and create a fair, secure and sustainable solution for its public pension nightmare. In any event, it appears that 60% of each chamber of the General Assembly must support any proposed bill in a Special Session this year.

There is time to develop the solution before the end of the year and have it considered by the General Assembly in January, but only if the Governor moves with dispatch. A Special Session held before July 1 can at least freeze the KERS-NH contribution rates for one year, create the Task Force, and come back later in January to receive the recommendations of the Task Force.

During the legislative session, one legislator asked me to craft a “Hail Mary” solution, which I did. It has now been circulated widely within the General Assembly membership and the Administration. What’s needed is for someone to become the “first mover.” One might even say “have a little faith, take a look at some of the church plans, and trust collective bargaining.” The “Hail Mary” solution is embedded below.

_________

[1]The two lawsuits basically seek indemnification from KRS for attorneys’ fees and, in the event of an adverse judgment, for the entire judgment. The general American rule is that, absent an agreement to shift attorneys’ fees, each party is responsible for its own fees and costs. KRS is not formally a party in the Mayberry litigation, so the hedge funds filed suit in Delaware in a plain example of forum-shopping. One could easily conclude that the real purpose of the Delaware litigation is to deter other state pension funds from considering litigation remotely like the Mayberry case.

00 Proposed Kentucky Retirement System Legislation

Thank you Yves.

After reviewing my pension fund’s increasingly opaque annual financial report, I plied (Retirement Fund) staff with an open records request regarding the advisory role of PE and Hedge Funds. Staff responded with three pages of answers to a number of questions. After some introductory remarks, here were my questions to (Retirement Fund) staff:

In the interests of transparency could you please provide me with further information on PE and Hedge Funds employed by (Retirement Fund) including:

Exactly how much 2018 (Retirement Fund) funds were invested with PE and Hedge Funds?

How exactly are PE and Hedge Fund management fees calculated?

Are any PE and Hedge Fund management fees extant that are not included under “carried interest”?

What is the “agreed upon hurdle” associated with PE and Hedge Funds?

What is the probable value of the “illiquid funds” based upon a presumption of immediate liquidity?

How much has (Retirement Fund) paid Private Equity and Hedge Funds in fees over the 10 year period?

Are (Retirement Fund) recipients allowed to review the contracts (Retirement Fund) concludes with these firms?

Staff was more responsive than I expected. But, as expected they tried a bunch of nonsense about “IRR” and “implied volatility”…kind of like the guys in Mid-town who used to do the pick-pea-under-the-cup routine. Fortunately, they are dumber than me and revealed that PE returns had been declining recently and they included this jem…“illiquid private credit is the laggard…we are not taking enough risk vs. High Yield Index.” So, they need to take more risk to try to reach their no longer attainable return goal!

I’ll keep you informed.

Just to confirm: “Quasi” is basically the same as what the Brits call a “Quango,” right?

Quango, actually Qango, is the Acronym for “Quasi non government organization,” which is somehow linked to the state, but does not include elected members.

Quasi: having some resemblance usually by possession of certain attributes.