By Jerri-Lynn Scofield, who has worked as a securities lawyer and a derivatives trader. She is currently writing a book about textile artisans.

The Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL) released a report last week, Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet discussing the significant and growing threat plastic pollution poses to the earth’s climate.

I’ve written extensively on the plastic crisis, concentrating largely on the waste management issues and the environmental damage plastic causes, particularly to oceans and marine life. By contrast, the CIEL report is the first report to estimate what the Guardian called “the greenhouse gas footprint of plastic from the cradle to the grave.”

CIEL examined each of four stages of the plastic lifecycle to identify the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Virtually all plastic begins as a fossil fuel, and greenhouse gases are emitted at each stage of this lifecycle, beginning with fossil fuel extraction and transport, then proceeding to plastic refining and manufacture, continuing through managing plastic waste, and finally,assessing the ongoing impact of this poison once it reaches oceans, waterways, and landscape.

When looked at from this perspective, what did CIEL conclude?

From the executive summary:

…With the petrochemical and plastic industries planning a massive expansion in production, the problem is on track to get much worse.

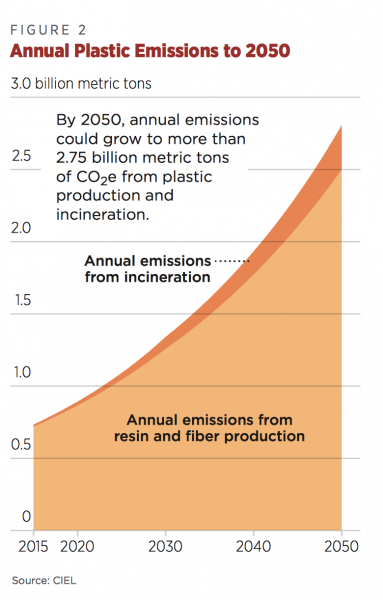

If plastic production and use grow as currently planned, by 2030, these emissions could reach 1.34 gigatons per year—equivalent to the emissions released by more than 295 new 500-megawatt coal-fired power plants. By 2050, the cumulation of these greenhouse gas emissions from plastic could reach over 56 gigatons—10–13 percent of the entire remaining carbon budget (see also the further discussion in CIEL report, pp. 3-5).

Source: Center on International Environmental Law, Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet , p. 5.

Think about that. Do we really want to continue to devote such massive greenhouse gas emissions to producing plastic?

The comprehensive study reports many worrying conclusions. To name just one, from the press release announcing the report:

Plastic in the environment is one of the least studied sources of emissions—and a key missing piece from previous studies on plastic’s climate impacts. Oceans absorb a significant amount of the greenhouse gases produced on the planet—as much as 40 percent of all human-produced carbon dioxide since the beginning of the industrial era. [The report] highlights how a small but growing body of research suggests plastic discarded in the environment may be disrupting the ocean’s natural ability to absorb and sequester carbon dioxide.

This means that not only do plastics cause considerable environmental damage to the oceans and their marine life, but that plastic may also be disrupting the ability of oceans to sequester CO2.

How is that so? From the executive summary:

Microplastic in the oceans may also interfere with the ocean’s capacity to absorb and sequester carbon dioxide. Earth’s oceans have absorbed 20–40 percent of all anthropogenic carbon emit- ted since the dawn of the industrial era. Microscopic plants (phytoplankton) and animals (zooplankton) play a critical role in the biological carbon pump that captures carbon at the ocean’s surface and transports it into the deep oceans, preventing it from reentering the atmosphere. Around the world, these plankton are being contaminated with micro- plastic. Laboratory experiments suggest this plastic pollution can reduce the ability of phytoplankton to x carbon through photosynthesis. They also suggest that plastic pollution can reduce the metabolic rates, reproductive success, and survival of zooplankton that transfer the carbon to the deep ocean. research into these impacts is still in its infancy, but early indications that plastic pollution may interfere with the largest natural carbon sink on the planet should be cause for immediate attention and serious concern (executive summary, p. 3; CIEL report, pp. 73-77).

Fracking Boom Driving Ramp Up in Plastic Production

One major driver of the rapid growth of the plastics crisis in the last decade: cheap natural gas produced by the fracking boom has led to a huge ramp up in plastic production, particularly in the United States (see my previous post Fracking Boom Further Spurs Plastics Crisis). CIEL notes the Gulf Coast and in the Ohio River Valley have seen a dramatic increase in plastic infrastructure. Sharon Kelly also explored this topic for DeSmogBlog in Why Plans to Turn America’s Rust Belt into a New Plastics Belt Are Bad News for the Climate).

CIEL predicts both the increase in fracking and plastic production will spread will only spread internationally from these US origins.

Let’s consider fracking first:

As a result of the shale gas boom in the United States, firms are investing heavily in new production capacity near shale formations. As of September 2018, projected investments in US petrochemical buildout linked to fracked shale gas amounted to over $202 billion for 333 new facilities or expansion projects.

The fracking boom in the United States has led suppliers to seek long-term supply contracts and export oversupplied gas. Liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities—and the pipelines, coastal terminals, and ships that service them—have accordingly become a growing component of fracking infrastructure to support these efforts.

This internationalization of the fracking boom has already started and is set to accelerate. In Argentina’s Vaca Muerta region, oil, gas, and petrochemical companies are working to open the second-largest fracking frontier on the planet and attract major petrochemical investments to exploit the fracked gas. In July 2017, the United Kingdom received its rst delivery of LNG from the Sabine Pass export terminal in the US state of Louisiana. The Cove Point LNG export facility in Maryland is now a point of transport for Marcellus Shale gas destined for Japan and India. As of the drafting of this report, ve additional LNG export terminals are in the planning stages in the United States. (CIEL report, p. 24, citations omitted; emphasis added).

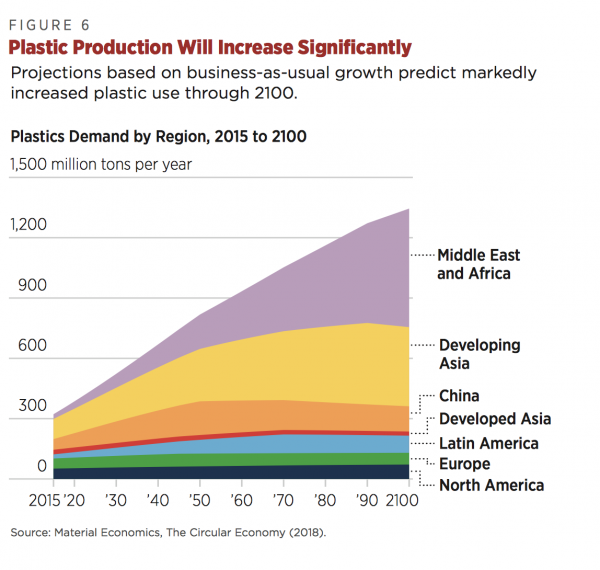

The CIEL report concentrates on the state-of-play in the US , in part as data for some other producers, particularly those in Mid-East countries (Iran, Saudi Arabia), is sparse (CIEL report, p. 26). CIEL nonetheless predicts that production of plastic will increase dramatically – absent major offsetting changes – and demand will skyrocket in places such as the Middle East and Africa and developing Asia.

Source: Center on International Environmental Law, Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet , p. 52.

Solutions: What Is to Be Done?

The CIEL report is detailed and comprehensive – but interesting and readable – and I encourage interested readers to take a look at it, as I cannot possibly do justice to it in this short post.

What I want to highlight here is that the report doesn’t just analyze the climate change aspects of the plastic crisis, but also proposes some potential solutions (see CIEL report, pp 82-83).

The first and foremost priority is reducing the production and use of single-use plastics. Now. This should be done not only because of the environmental damage plastic waste causes, but because to do so would also reduce the greenhouse gas emissions created during the plastic lifecycle.

Some other solutions CIEL recommends include:

- stopping development of new oil, gas, and petrochemical infrastructure;

- fostering the transition to zero-waste communities;

- implementing extended producer responsibility as a critical component of circular economies; and

- adopting and enforcing ambitious targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all sectors, including plastic production.

The report doesn’t mince words in dismissing low-ambition strategies and false solutions – which CIEL emphasizes do more harm than good:

Complementary interventions may reduce plastic-related greenhouse gas emissions and reduce environmental and/or health-related impacts from plastic, but fall short of the emissions reductions needed to meet climate targets. For example, using renewable energy sources can reduce the energy emissions associated with plastic but will not address the significant process emissions from plastic production, nor will it stop the emissions from plastic waste and pollution. Worse, low-ambition strategies and false solutions (such as bio-based and biodegradable plastic) fail to address, or potentially worsen, the lifecycle greenhouse gas impacts of plastic and may exacerbate other environmental and health impacts (emphasis added; executive summary, p. 4).

The report devotes considerable space to debunking some of these low-ambition strategies and false solutions to the plastic crisis (see pp. 83-85). Some of these include: using renewable energy to fuel the plastics supply chain; expanding modern landfilling practices; and cleaning plastics from the open ocean (I think this point is a reference to the Ocean Cleanup Array project, an attempt to sequester the huge agglomeration of plastic that comprises the Great Pacific Garbage Patch,see my post, Plastic Watch: Ocean Cleanup Array to Arrive Today in Hilo for Necessary Repairs, which also includes links to other posts on the topics).

Other false solutions CIEL discusses rely on what I’ve called the “technofix fairy”, allowing us to pretend we’re addressing the issues without having to make rapid, necessary changes to the status quol. These mistaken panaceas include: switching to biodegradable plastics, including some made of biofeedstocks; employing plastic-eating organisms; using chemically recycled feedstocks; and incinerating plastics under the guise of waste-to-energy. In the interests of keeping this post to manageable length, I won’t discuss these points further here, in part because I discussed the fallacy of the technofix fairy in a recent post, Plastic Watch: Debunking the Technofix Fairy, Biodegradable Bags Don’t Degrade (although I might return to this aspect of the topic in a future post). Just as with similar panglossian solutions that over-rely on intervention from the close relative the recycling fairy – one should be skeptical of simplistic solutions to this complex and crucial crisis.

The takeaway from the CIEL study:

Ultimately, any solution that reduces plastic production and use is a strong strategy for addressing the climate impacts of the plastic lifecycle. These solutions require urgent support by policymakers and philanthropic funders and action by global grassroots movements. Nothing short of stopping the expansion of petrochemical and plastic production and keeping fossil fuels in the ground will create the surest and most effective reductions in the climate impacts from the plastic lifecycle.

Reducing use of plastic – particularly, single use and wasteful and unnecessary packaging – is only one crucial necessary step. As I like to allow in a small ray of optimism, even in what is otherwise a depressing post, allow me to close with some details from The Guardian:

Throwaway plastic packaging makes up 40% of the demand for plastic, fuelling a boom in production from 2m tonnes in the 1950s to 380m tonnes in 2015. By the end of 2015, 8.3bn metric tonnes of plastic had been produced – two-thirds of which has been released into the environment and remains there.

“Packaging is one of the most problematic types of plastic waste, as it is typically designed for single use, ubiquitous in trash, and extremely difficult to recycle. A constant increase in the use of flexible and multilayered packaging has been adding challenges to collection, separation, and recycling,” the researchers said.

Forty per cent of plastic packaging waste is disposed of at sanitary landfills, 14% goes to incineration facilities and 14% is collected for recycling. Incineration creates the most CO2 emissions among the plastic waste management methods.

Eliminating throwaway plastic packaging isn’t a complete solution to the plastic crisis. Not by a long shot. But it’s one that could be relatively easily implemented – if policymakers were willing to take on the plastic pushers. It would reduce global greenhouse emissions – whereas continuing current policies and trends, will only further exacerbate climate change.

Problem remains: neither US political party will run any candidate who would take efficacious action, as the DCCC’s reaction to the 2018 elections having scared their patrons? As the fracking Ponzi scheme now depends largely on potential wet-gas cracking for multinational conglomerates, they’ll have some difficulty selling “energy security” & “jobs” that’s consisted of LA, TX, OK hands claiming $600 PA unemployment checks for half of each year? Somebody has to tend all the leaky well heads. We Appalachian hillbillies have developed quite an aptitude?

https://insideclimatenews.org/sites/default/files/documents/1982%20Exxon%20Primer%20on%20CO2%20Greenhouse%20Effect.pdf

https://www.google.com/amp/s/amp.iflscience.com/environment/exxon-scientists-predicted-this-weeks-co2-emissions-milestone-over-35-years-ago/

https://undark.org/article/methane-global-warming-climate-change-mystery/

Interesting about CO2 impact from incineration. In the EU and Eastern US incineration is a dominant means of disposal. “Waste to energy” they tell us.

As a kid in the 1960s, plastic was a rarity in most packaging. Now in our pantry plastic predominates. I have plastic squeeze bottles for garden use that are 10+ years old. And you find that stuff in the ditches that blow out of the recycling truck.

I cannot see how capitalism or GND can possibly put an end to this destructive madness.

Thanks for your ongoing coverage, Jerri-Lynn

Even the incineration industry acknowledges that you get less energy from burning plastic than is saved from recycling it.

But the relationship of plastics to incineration is more insidious than first appears – for modern energy to waste burners to operate efficiently they must have a minimum calorific value of weight. That means that they need plastics in the mix, so the industry itself becomes a mover in promoting plastic waste, especially petrochemical derived plastics (PVC is problematic in incinerators). Essentially, if you take out most of the stuff from waste that is either compostable or easily recyclable, the residual doesn’t burn very well, and thats a huge problem, especially when municipalities are tied into long term supply contracts to incinerator companies.

Our “resource recovery agency” is locked into a long term contract with Covanta. The incinerator was rehabbed at considerable expense to burn plastics.

Curbside recycling was effective locally, over 40% which is quite high for the US. Before the recycleD material quality mandates from China, there wasn’t enough trash to burn efficiently, so they were importing garbage from adjacent counties. In Niagara Falls there is an enormous incinerator that imports trash from downstate N Y and NJ in freight trains, 30 to 50 cars at a time!

Ag plastics are a huge issue in rural areas. The have completely replaced barns and silos. Much is burned in open pits by farmers or is landfilled.

I’m afraid it is hopeless. Was never this bad 30 or 40 years ago. I cannot see the US having high taxes on single use plastics, high value deposits on containers or high taxes on all plastics.

Solution?

One dollar deposit, paid on return of recyclable plastic containers, to be returned to manufacturer, who is responsible for the disposition of the items. That will drive them to paper or glass.

Outlaw all throwaway plastic, straws, stirrers, cups or Tack an onerous fee on it to make it cost prohibitive.

Extra fees on non-recyclable plastic.

If the state can tax and control the sale of gasoline, they can do the same for plastic.

Let Mister Market do his magic.

“Let Mister Market do his magic.” produces a lovely image in my brain!

Please correct me if I’m wrong. My understanding is that very little plastic is actually recycled (not returned for recycling but actually turned into a new plastic item) because the material degrades in the process. So a recycled milk bottle, say, is almost never turned into a new milk bottle. At best it may be converted to coarser plastic used in outdoor decking and furniture. At worst it just piles up somewhere. Is recycling partly a myth to encourage continued consumption without ecological worry?

All this soul searching, rending of hair, and gnashing of teeth is ridiculous. Just put a price on plastic. Try 5¢/lb. If this doesn’t get all the plastic collected, try 10¢/lb but I can assure you, at some point market forces will clean up the planet lickity split.

Politicians are dumb else this would be what Bernie and others would be advocating. While you’re at it clean up India too by pay individuals there at the same rate/lb as we do here. After all, we really want it cleaned up worldwide, right?

Yes, this entails building ships and infrastructure to transport it here to be processed but we can do this and create jobs in the process. It just entails political will and a focus on things we can attain. Start with setting the price of used plastic. The rest will follow like the second step.

The point is there is a price for used plastic. What are we, USD$20T in debt now? Establish the price for used plastic and print more monopoly money to pay for it. Duh!