Lambert here: Looks like if “take back control” is your only goal, everything might end up OK. Otherwise…

By Matthew Bevington, EU researcher, The UK in a Changing Europe and Jonathan Portes, Professor of Economics and Public Policy, King’s College London; and Senior Fellow, UK in a Changing Europe. Originally published at VoxEU.

Three years on from the referendum, it seems like a good time to take stock of whether the Brexit process so far has been good or bad for the UK, and its likely future impacts. This column does so based on four tests covering the economy, fairness, openness, and control. While the apocalyptic predictions of the Remain campaign have failed to materialise, the economic damage has nevertheless been significant. And although the UK may end up with considerably more control over a range of policies – trade, regulation, and migration – than at present, the difficult issue remains of what future governments will do to address the underlying discontent that, at least in part, drove the Brexit vote.

Economists’ opinions on Brexit are often dismissed as politically biased or driven by groupthink. While these charges are overstated, it is legitimate to point out that assessments of the impact of Brexit that focus narrowly on its impact on GDP miss broader economic and social concerns – for example, inequality and regional disparities (e.g. Whitaker 2018) – as well as explicitly political issues, in particular sovereignty. In early 2017, therefore, academics at the UK in a Changing Europe – some of us, but no means all, economists – set out four ‘tests’ for Brexit (UK in a Changing Europe 2017) that attempted to take account of that wider context while setting out some objective criteria by which the success of Brexit could be judged.

We argued that the referendum campaign had revealed some key themes and issues that underlay the British political debate. Our tests, therefore, reflected this broad consensus. They were the following:

- The economy and the public finances: Would Brexit make the country better off?

- Fairness: Would Brexit help some of those individuals and communities who have not benefited from growth over the past 30 years?

- Openness: The UK has a long and well-established consensus, across the political spectrum, in favour of free trade and open markets as a means to greater prosperity. Would this openness continue, and even go further?

- Control: Would Brexit enhance the democratic control the British people exercise over their own economic destiny?

We deliberately chose not to frame the tests around the key issues that are the subject of the negotiations between the UK and the EU over the terms of our withdrawal and our future relationship.

Of course, the UK has not left the EU yet, and there is a plausible chance that it may not do so. Nevertheless, Brexit is a process, not an event. Three years on from the referendum, it seems like a good time to take stock. Has the Brexit process, so far, been good or bad for the UK, and what can we say about its likely future impacts on each of the ‘tests’ described above?

The Economy and the Public Finances

There is little doubt that the impact of the Brexit vote on the UK economy has been negative (Springford 2018). The sharp fall in sterling pushed up prices without doing much to boost exports, and uncertainty has reduced business investment (Crowley et al. 2019, Breinlich et al. 2019). The UK is clearly poorer as a result. Both growth and tax revenue appear lower than they might otherwise have been, although the labour market has remained resilient. Nor is there much sign of any reduction in macroeconomic imbalances. While far from disastrous, and far from the apocalyptic predictions of some in the Remain campaign, the overall direction is clear.

Figure 1 Sterling effective exchange rate (2005=100)

Source: Bank of England

A Brexit deal would reduce uncertainty and strengthen the pound, and it might result in a short-term boost to growth. But the overwhelming consensus among economists, both independent and within government, remains that leaving the Single Market, as envisaged under the current Withdrawal Agreement and Political Declaration, will have a significant and negative impact on UK trade with the EU (Department for Exiting the EU 2018). The impact of a no deal Brexit – even leaving aside the unquantifiable potential short-term disruption to trade and the wider economy – would be even greater (UK in a Changing Europe 2018). Nor, given the current geopolitical environment and US trade policy, does it seem plausible that trade deals with third countries will provide much compensation (Department for Exiting the EU 2018). Even if the UK were to reverse course and remain in the EU, there would still be some lasting damage to our international reputation for political and economic stability. While huge uncertainties remain about the long-term economic impacts of Brexit, it seems highly unlikely to be positive. The question is how large the damage will be.

Fairness

Pressures on public services, in particular social care, education and policing, have intensified. While Brexit is not the main driver here, it has certainly not helped (Office for Budget Responsibility 2018). Cuts to benefits mean that inequality and child poverty are rising, albeit only marginally, mitigated to some extent by large rises in the National Minimum Wage (Department for Work and Pensions 2019).

Although real wage growth has recovered somewhat, there is little evidence that reduced EU migration is boosting pay growth at the bottom end. More broadly, there is no sign of substantial new policies to address the ‘left behind’ areas and communities that some argue drove the Brexit vote. Indeed, the preoccupation of the government, media, and political system with Brexit has meant that policy development in areas from social care to regional policy has largely stalled.

There is little prospect of this changing in the short to medium term. Most forms of Brexit will worsen the government’s fiscal position, probably significantly, reducing the space for new policy initiatives. Furthermore, the planned Spending Review is likely to be postponed. Although this is highly uncertain, the impacts of Brexit on regions and sectors are, if anything, likely to disadvantage those which are already lagging behind, although it is possible that targeted migration policy – joined up with continued rises in the National Minimum Age and action on education and skills – might over the medium term help the lower paid and less skilled.

Openness

The UK remains a relatively open economy. Indeed, the conclusion and implementation of further EU free trade deals has led to some modest further liberalisation, while there has been some relaxation of restrictions on non-EU immigration. However, perceptions have changed, and not for the better. This has had a clear real-world effect. The UK has certainly become a less attractive and welcoming destination for potential EU migrants, and the evidence suggests that Brexit has reduced both trade (REF) and investment flows (Serwicka and Tamberi 2018).

It is possible that in theory these impacts are temporary and could be reversed by post-Brexit policy choices. In particular, both the public and policy debate on immigration have turned in a more positive direction, and it looks at least plausible that, whatever happens on Brexit, the UK will choose a relatively liberal approach. On trade, and perhaps investment, however, the nature of the trade-offs means that it will be difficult if not impossible to reduce barriers with third countries without erecting them with the EU. Given the uncertainties over future policy, the prognosis is mixed.

Control

In a legal sense, as long as the UK remains an EU member, there is no sense in which either Parliament or the people have ‘taken back control’. Indeed, to the extent that the UK is marginalised or irrelevant in EU decision making, we have arguably lost control to some extent. Meanwhile, efforts to devolve decision making within the UK have stalled. Public perceptions reflect this.

However, this is perhaps the inevitable result of the Brexit process. While it is simplistic to suggest that on Brexit Day (or even after the end of the transition period) there will be a sudden shift, over time the UK will increasingly reclaim the ability to set its own policies – subject to the economic and political constraints faced by all countries – on trade, investment, and regulation. Translating that into a sense among the broader public that they have genuinely increased their own agency over decisions that shape their lives will, however, remain a challenge.

Conclusion

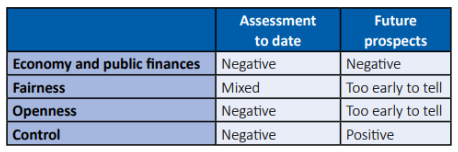

Our conclusions are summarised in the following table.

Our verdict on the impact of the Brexit process so far is unsurprising and unequivocal. While the apocalyptic predictions of the Remain campaign have failed to materialise, the economic damage has nevertheless been significant: not just a one-off inflation shock, but also more persistent impacts on investment, trade and migration, meaning the UK is already a somewhat less open economy. Nor is the UK, in any measurable sense, a fairer society. However, the seismic political impact of Brexit means that the UK has paradoxically lost control, at least temporarily, over some aspects of our economic future.

But these are early days, to say the least. Our judgement on the future prospects for Brexit is therefore necessarily more tentative. We can say with some degree of assurance, based on the consensus amongst credible economists, that Brexit will, overall, be negative for the UK economy and public finances. Indeed, that consensus has if anything been strengthened by developments so far, as the prospect of any Brexit that retains Single Market membership and free movement appears farther away than ever.

Correspondingly, however, this means that the UK will indeed have considerably more control over a range of policies – trade, regulation, and migration – than at present. The challenge of how to translate that gain in notional sovereignty into a genuine sense amongst the electorate that they have a real say will be central to British politics after Brexit. And the most difficult and uncertain issue remains what future governments will do to address the underlying discontent that, at least in part, drove the Brexit vote.

Take back control, if I may resort to hackneyed phrases, was always for those of us who supported Brexit what it was all about. If you’re wanting to live under a model of a sovereign state making political decisions and determination of policy via a system of directly elected representatives, then that — sovereignty (or “control” if you like) — is what is required.

Conversely, if you want your state to become party to a federal arrangement (where some matters of policy are devolved or start off being then continue to be devolved, but not all, and the “centre” can subsume any such devolved matters back to the federal control as and when it wishes) then fine. Go for the federalism option.

Personally, I never cared much at all which we had. What I was not prepared to continue any long supporting (and bear in mind I’d supported EU membership all my life) was EU cakeism. Which is, more fully expressed, that the EU could continue to acquire control (“competencies” as the EU describes it) but fail to update its governance structures to better reflect the ever-increasing powers it was acquiring over public policy areas.

I gave the EU a long, long time to get its act together. Reduce the roll of the Commission to that of a more traditional civil service i.e. implementation of policy but not policy making. Drastically reduce the powers of the Council to either become more of a cabinet-like system along the lines of the U.K. system or, otherwise, separate executive powers into the Council along the same boundaries as the US presidency does. Power — true power, political and policy matters — should lie with the directly elected European Parliament.

If there’d been the slightest, merest hint that some kind of governance reform was at least being considered by the EU — not even specific plans, just a firm indication of a direction of travel — all would have been forgiven. But no. Just the opposite as the current unseemly back-room dealing over the Head of the ECB, the President of the Council, the President of the Commission and the EU foreign affairs representative role allocation demonstrates.

I recognise a tyranny in the making when I see one. Know how I know? ‘Cos I can feel it. No, it’s not scientific standards of proof. Just like you guys “knew” that, bad though Trump is, Hillary Clinton would have been worse. Not on paper. Not even on policy. Certainly not on, moreover, concepts like creating a better or fairer society than Trump is. Clinton would have been less-bad. Just as with the U.K. — being in the EU would be “less bad” for a variety of measures. But longer term? All those endless “less bads” don’t equate to an eventual result of “good”.

I’m fed up of “less bads”. I want a shot at “better”. That’s the gamble for the U.K. — if it does really go through with Brexit. It might well end up with a “worse”. Or even a “much worse”. But the choice will be ours. No EU membership to “save us from ourselves” (while all the while building itself into who-knows-what). We’ll get the country we deserve, whatever that turns out to be.

Well put. Clarifying and useful. I voted remain but share exactly these concerns.

Austerity – ?????

Yes, the ECB and the Commission definitely approves of that. I think they even made Member States sign up to a treaty mandating its implementation.

Your Tories believe in it as well. So much they tired, of the soft liberalism of the EU.

What does that have to do with its implementation in the U.K. let alone its additional track record WRT TINA, albeit I could say the same for the U.S. for that matter.

From the link:

If the U.K. government hadn’t done this, the Commission would have made it. Kind-a like Italy, France, Greece… they do seem to be serious about it.

Of course, the U.K. government could have put up a bit of a fight, rather than saying, as they did, gleefully, “yes, yes, bring it on”.

Of course of course, that doesn’t seem to have done Italy any good.

Nothing whatever in the quote indicates austerity. It simply implies that expenses and income ought to more or less balance over the longterm. The difficulty here is entirely practical because the EU was created by and allowed to join some financial parasites like the City of London, Ireland, or Luxembourg. These traitor states initiated a race to the bottom regarding taxation within the common market which makes the life more difficult for everyone.

I wonder what you see in the UK if the EU is a tyranny in the making given that the Uk in most cases does not care one ioata about human rights at home or international law abroad. (cf. Surveillance powers aka “Snooper’s Charter”, Chagos Island and other (ex-) colonies, Belgacom attack, interception of transatlantic fibre optic cables, Iraq War and support for other US, Israeli, and/or Saudi crimes, the House of Lords and the bloody monarchy itself, concentrated and sometimes secret land ownership, etc, etc…

Italy desperately needs fiscal stimulus. The EU is taking active steps to prevent the Italian government from doing this. The reason is that Italy’s budget deficit and GDP/Debt ratio are deemed “too high” under the rules prescribed in various EU treaties. If this isn’t the EU enforcing austerity, I’m struggling to understand who is asking Italy not to undertake the public spending expansion is wants to do.

Blaming this- or that- Member State for “causing” this policy lets the EU off the hook. The EU is the sum total of Member State policy direction, but how can this be overturned? The Commission persists long, long after any particular Member State government gets moved on. And changing the EU requires unanimity as treaty changes must be passed in each Member State. Thus, the endless ratcheting up of neoliberalism continues more-or-less unchecked.

And I’ll see your war with Iraq and raise you an EU meddling in the Ukraine.

I’m not against the EU. I profoundly wish it would mend some of its wicked ways so I can fall in love with it all over again. But carrying on like the EU is the most perfect expression of regional powerbroking evah is just as one-sided and ultimately self-defeating as Daily Telegraph-like endless beating up of the EU without looking at the flip-side.

A recent Bruegel post in the links section showed that the decline of Italy has been going on for 30 years (unlike say Greece) which indicates structural reasons quite impervious to any fiscal stimulus. And one aspect of the desired actions of the current Italian government are further tax cuts – a stupid and ultimately self-defeating policy. The EU fault in regards to Italy is that it hasnt acted a lot sooner during Berlusconi or even earlier.

I never painted the EU as perfect. I simply pointed out that the budget rules only lead to austerity because either national governments mess up over a long time and then choose austerity to comply with the rules or because tax competition within the common market erodes the tax base of non currency issuing States/local governments which inevitable leads to cuts. A balanced budget as envisioned by the rules needs to be implemented over years or decades meaning cutting back spending or increasing taxation in good times before the next crisis happens. This way there is plenty room for fiscal stimulus instead of 100% or more debt to GDP.

The obligations on the UK differ from those placed by Article 104 upon other member states (see Protocol 15) so that the UK has to ‘endeavour to avoid’ deficits rather than actually avoid them. So the situation is not exactly as described in your quote. The Commission has of course never sought to take action against the UK but obviously it would have been easier for the UK to argue it had ‘endeavoured’ to take action but failed to avoid an excessive deficit than if it had been subject to the same requirements as other member states.

“The U.K. could have argued…” is not the same as “the U.K. could have decided, unchallenged by anyone, to do…”

A simple distinction. But a crucial one.

I seem to remember the opining salvo of Brexit was something about going rogue tax haven with raspberries on top of it.

Did anyone actually get taken to ECJ on this, and if they did, why didn’t they bring in a precedent of Germany?

Sounds like the Commission is filling in the forms right now https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/05/eu-could-fine-italy-3bn-for-breaking-spending-and-borrowing-rules

Italy could say “we’ll see you in court!”

But I’m all ears about what their defence will be. “Rules based organisation”. etc. etc.

Oh, dragging in the example of Germany/France etc. happily ignoring the rules for quite some time may not be a perfect defense, but it will create a lot of publicity.

The CJEU is not a common law court. Precedence and “real world” practice isn’t an arguable point.

That’s not strictly true – precedent and established practice is not given the same weight in the CJEU as in Common Law areas, but arguments based on precedent (including US Supreme Court Decisions) are commonly held and accepted.

Its more precise to say that the CJEU will not allow precedent or practice to overcome clearly written statutes. But there are plenty of examples where the application of Directives is not unambiguous, and the Courts have always allowed argumentation on those points. This has been particularly noticeable in decisions relating to the EIAR and Habitats Directives.

I understand that perfectly well, and my post said it was not a perfect defense.

My point is that Italy showing out very publicly, in the EC courts that Germany was able to get away with it, so that Germans and French can get away with things but others can’t – and, even better, bringing in a case against them – will raise a lot of very very unpleasant questions for German/French etc. politicians, which they are not really keen to answer right now, if ever.

So the whole thing could be more politican than judicary. And the “special treatment” of Germany and France is hated by all the remaining EU members, so Italy could get quite a bit of support here if it played it well. Here, IMO, is what the UK is giving up, because it was always seen as – at least a possible – counterweight to France and Germany, and could have got support from quite a few mid/small EU countries.

But it ultimately decided to use that to its own purposes (City, financial services) rather than strategically – because, strategically, it would have to commit to the EU, which domestically would have dropped the best whipping boy one would have wished for, and accept the responsibility for lot of issues themselves (mind you, porking the EU directives and they saying “the evil EU told us to do this” is common elsewhere, not just in the UK, but only in the UK the press industry made it its own so fully).

Legal Action before the ECJ is explicitly excluded: TFEU art.126.10 . So thats never going to happen…

You’re perfectly allowed to see “tyranny in the making”. I, on the other hand, have absolutely no idea what you are talking about. Is the EU perfect ? Far from it. But when you say you demand a “merest hint that some kind of governance reform was at least being considered” what you actually mean is a “firm indication of a direction of travel”. We have the former, it’s untrue and unfair to pretend otherwise, we will never have the latter precisely because the EU is not a tryanny.

If you want an example of tyranny in action, you can look at the treatment of greece.

I’ve seen a lot of talk, some here, about how awful the greek polity was.

Looking at its last 80 odd years, it has hardly had a chance and it would have probably benefited from a little time muddling along on its own.Little of the exogenous help it has had has worked out well.

I am in sympathy with Clive, though I voted leave to relieve our population of the illusion that it was someone not of our kind that was furiously making life outside the walls as miserable as possible.

Quixotic certainly, destructive probably.

The strange thing is that the curtain has been swept back, incompetence and malice laid bare, yet attitudes have just ossified.

Good job, conglomerated 1st to 4th estates!

You mean when they had conditions on loaning Greece money?

Oh those scoundrels.

More than “conditions”, it was on-your-knees, pound-of-flesh conditions, payday-loan conditions, very obviously punitive. Agreed that the EU governance structure is much less than democratic, the parliament being almost window dressing. Any governance that lets the same unelected last names keep reappearing in positions of power (Barrosso comes to mind) ain’t right.

And yeah, they also let things slide when it suits them…witness the kabuki around Ireland’s multinational business taxation. Always complaining but never really coming down hard, not even during the whole IMF crap. 1% levies on your dole, fainting couch and vapors over the tax but no action. Harrumph.

First hit is free, then you have to work, or sell everything you have.

Noone explained the t&cs to ‘greece’.

Little of the exogenous help it has had has not worked out well

should read

Little of the exogenous help it has had has worked out well

No one, and again, I’ll stress it, no-one forced Greece to enter the EU, or to take up EUR. It was their own choice. Look at Sweden, Austria and Finland who joined only in 1995, later than Greece or Portugal.

TBH, where I do see a large problem with the EU is that even when it does recognise that a country is unfit, it still, for various reasons, lets it in.

Greece was a prime examples of the earlier expansions. Romania and Bulgaria more recent ones.

True as far as it goes. But I don’t see that this justifies the behavior post 2010.

I don’t have hope that it will change your narrative of the big bad EU but:

https://medium.com/bull-market/the-shortest-greece-post-ever-52963439abfb

I have no such view. My view is rather mixed – as I said above – I voted to stay.

This link makes no difference to that position. I don’t think it adds much to the debate at all. I have read a number of books that cover the Greek situation in some detail. The behavior towards the Greek people was very poor.

I wrote it elsewhere – I do believe the EU could, and should have behaved better.

If nothing else, it should have recognised that while a lof ot the harm was self-inflicted, the banks (french especially IIRC) were a very important enabler, and the ECB regulation was one thing that helped with that.

In my mind, there are no white knigthts here, and the EU is guilty as charged of not learning the lesson (or worse, taking the wrong lesson).

But ignoring the role Greece played its catastrophe is wrong too – and it doesn’t seem to have learned the lessons either.

Yep, even with all those misbehaviours the EU treatment for Greece was quite disgraceful, somehow rooted in some old christian way to treat the sinners that should have been abandoned long ago.

Ignoring the role of the greek elite is the matter.

Greece is comprised of normal human beings who do not meet the rational expectations requirements demanded by the EU.

Their representatives failed them,not they them.

Greek voters voted for Greek elite. How’s that absconding the Greek voter of responsiblity?

Each, and I mean each, no matter the form of government, nation has the government it deserves. If you want a better government, it will not come gifted by the heavens. You, yes, you personally, have to spend some effort to make it so. If you don’t, well, tough luck, you get what’s there.

You are always talking like everyone involved had perfect clairvoyance, especially since the present iteration of the EU was a process and was not born full-grown from the brow of Zeus. And was the question ever put to the Greek people at large, as in a referendum? My understanding is that it wasn’t.

So again, as in another thread, I will say…. I will never agree that the way the Greek people were treated by the EU was deserved.

All countries had to ratify Lisabon. Greece could have chosen not to. Same for any and all treaties. And yes, Ireland had to vote twice to get there – but so what? Are you saying that those referenda were not free, and someone was marking Irish people ballots for them? I’d like PK/someone else Irish to answer that, unless you happen to be Irish, or lived there at the time.

I will repeat myself too. The EU could have, and should have, treated Greece differently. But ignoring the Greek part in the whole debacle is simply biased.

Especially if you look at Portugal, or if you want someone who was really mistreated by the EURzone, Spain. Yet Spain, even with similar history of military dictatorship, variously corrupt economy and distorted banks with stupid real estate market performed way better in the end.

And as to the referendum – and so what? The EU does not tell its candidates how they should or should not run the process internally. If they decide on the referendum (say the Czech Republic did before its ascension), that’s fine. If they don’t it’s not the EU’s problem.

Greece if fact had elections in 1981 and 1985. I’d be really surprised if the major parties in both didn’t have the EU ascension as the large part of their manifesto. People were free not to vote for them, as I don’t doubt that say the Communist party of Greece was strongly against.

Implying that the Greeks were forced to join the EU (by whom????) is just dumb.

No one, and again, I’ll stress it, no-one explained to ‘Greece’ what it would be demanded after they had entered the EU.

Irrelevant. Did someone explain to you in your first marriage what it was really about? How about having a first child? First, or any job? Signing any contract over five pages?

Rarely, if ever, you get explained what your choices mean in full.

I have to say that I agree with Clive on this one. It may have been better if Europe had stayed with a Common Market regime rather than a European Union. Any union of people that range from Scandinavia to Spain to Eastern Europe to Malta should have a flexible regime to accommodate the different peoples and their cultures. Instead, what I have seen is power being shifted up to a small group of people that are unelected and virtually unaccountable. In another time and place you would call that an oligarchy.

What is worse, this same group is of a neoliberal persuasion and we have seem them make “examples” of disobedient countries. We have seen time again too how the neoliberal idea of austerity is both unworkable & counterproductive but Clive has pointed out that this is mandatory by treaty. That is crazy that. To cap it off, the EU appears to be degrading the role of individual countries which removes a layer of protection for the people of the EU. The UK may become a train-wreck before long but they may have a better future long term than the citizens of the EU.

There are different visions on this and I would express it differently. It may have been better if Europe had tried to strengthen the political ties within rather than expanding geographically. In the end we had a strange mixture of “UK’s” will (geographical expansion) with “French” will (political integration). In my opinion, economical integration MUST be accompanied by political integration but there is where the powers that be love creating this limbo where they can cheat…hums… operate with more degrees of freedom. The kind of “openness” preferred by UK and many other EU elites.

All the main EU leaders are politicians. Those that are not directly elected are nominated by people who are. The “unseemly back-room dealing” Clive is complaining about is a direct result of the recent Europeans elections and the decline of the center-right party. The next Commission will be filled with people with extremely different background. It’s messy, it’s obscure but it is definitely a form of democracy.

Meanwhile the UK is ruled by a small group of people who all went together to the same boarding school a few decades ago. Is that really better ?

Finally, neoliberalism is an anglo-saxon thing. Thanks to the Germans, we have ordoliberalism in Europe.

The UK parties with the FPTP don’t do compromises. They do my way or highway, and it shows. The backroom dealing happens not between the parties, but within the “broad tent” (hahaha) of the parties.

Except the broad tent parties in the UK are falling apart.

This, I think, is the core of the issue the UK has with EU politics. The UK system is supposed to be ‘winner takes all’ – whether at local or national level. UK politicians simply don’t know how to do the horsetrading and compromising that are the meat and drink of most other EU countries.

The sort of government that, for example, the left has just formed in Denmark is very difficult for British politicians can deal with (I exclude Northern Ireland from this, as strategic voting and backroom deals are very important in NI, but that’s a specific outcome of the structure of local politics there)

The TFEU clearly mandated that the Spitzenkandidat system should be used to select the President of the Commission. That’s what everyone understood the wording of the treaty so required the Council to do — they were expected to “take into account” to the outcome of the European Parliament election and adopt the leader of the leading party group.

But of course this turned out to be the drearily familiar EU faux democratisation reform at its worst. As soon as the ink was dry on Juncker’s selection, Council naysayers (and some in the Parliament) called time on Spitzenkandidaten https://www.neweurope.eu/article/in-defence-of-the-spitzenkandidaten-process/ and brought it to its present sorry state.

Predictably, the current candidate under Spitzenkandidaten has been found by enough on the Council to have “issues” with “experience” and “qualifications”. Council shakers and movers would like someone more “suitable”. The result of the European Parliament election get “taken into account” ? Ha! Bollocks to the TFEU, then, say a chunk of the Council. Let’s shoehorn in someone “appropriate” like that nice Michel Barnier. We know where we are with him. No whiff of any of that populist nonsense of that deplorable Orban, either.

Messy and obscure? That’s one way of describing it. For me, citing just about the worst sort of sham democratic processes which the EU is notoriously bad for slipping into as somehow being symbolic of the EU’s-supposed moves to better transparency as being a direct result of the European Parliament election is so completely a reversal of reality, I can barely imagine we’re living on the same planet, let alone the same continent.

I do think you’re overestimating the “democratic” quality of how nations choose their leaders (Yves got what I was driving at below, there might be difference in degree but saying the EU is an oligarchy and the UK a democracy is being blind to realities). As for the EU, Weber would not have any trouble becoming Commission President if its party had won a majority in the Parliament. The EPP has less than 30% of the seats, why should its candidate be nominated ? The Spitzenkandidaten was never mandated by the treaties, it’s an invention of the EPP to stay in power even with only a relative majority, I don’t see what’s democratic about that. The one that will ultimately get the job will have to have the support of a majority of the Parliament and, if you have followed at all political news recently, party leaders in the EP made quite clear that they will not accept just anybody.

As vlade and PlutoniumKun said above, the kind of negotiations that are currently going on are standard practice in many european countries. Just one example: the current PM of Italy has never been elected and was unknow to the public just a year ago, by any measure, he has less democratic legitimacy than any EU leaders, is Italy undemocratic ?

As for “the EU’s governance isn’t any worse than any particular Member State’s governance”, I covered that at the top. Two wrongs don’t make a right and I have had it up to here with the endless less-bad’ery.

EU-bots chiming up relentlessly with the “I don’t understand Brexit, I don’t understand Brexit, it’s not like the EU isn’t that much worse than how the U.K. works” completely ignores that the U.K. has a free choice as to whether or not it should continue with its membership and factors such as the quality of the political institutions are in play and are in part why Leave won. And Remain hasn’t yet been able to turn the corner and revise that result nor does it show any particular signs of doing so. The EU governance structures continuing to operate in full-on “we don’t give a stuff” mode is not going to help. Handing off sovereignty is a decision that requires national consent and that consent can and will be withdrawn if the EU is demonstrably a repeat bad actor.

The Commission clearly interpreted the TFEU to adopt the

Spitzenkandidat candidate and made specific references to the 2014 selection of Juncker

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-8-2017-0049_EN.html

If the Council wants to throw out Spitzenkandidat, it can’t just say, as it is now doing, “oh, well, we’re not so keen on that any more, not if it turns out candidates like Weber, were going to decide by some other mechanism we didn’t tell anyone about before the European Parliamentary elections, none of us any made any mention of in any of our national elections where we came to power and never put up for debate, let alone got anyone to vote for it; in short, we’d rather return to the backroom dealing.”

If you’re happy that the words in the TFEU mean precisely what the Council says they mean, then fine. Just don’t expect me to vote “Remain” if that’s how the EU intends to carry on. And don’t be surprised, either, if the populism backlash continues apace. The EU was a nice grift for those who benefited from it while it lasted, but there’s absolutely nothing that’s written anywhere which says it must and will continue for all of time.

Again, in 2014 Juncker was supported by a majority of the EP. It’s not the case for Weber. I struggle to see why the Spitzenkandidat should be the only way to take into account the results of the EP elections especially when the EP itself doesn’t want it. And, in France at least, Macron was quite clear that he and his party wouldn’t feel bound by the Spitzenkandidat and I don’t recall many other French politcians making a strong defence of it. And again, it is a feature of many countries where Parliament is very fragmented that Executive Leaders routinely come out of nowhere, supported by a coalition put in place after the elections (was the case in France during the 3rd and 4th Republic).

I sincerely get that it might offend your view of how democracy should work. And, in politics as in law, appearances are important. If you want to leave the EU because of that, you have that right, I won’t deny that.

The council must “consider” the SPK. There is no obligations on them to accept them.

In the UK, the Queen must consider the suggestion of leaving PM, but is not bound by it (except by custom, which, as we found in the UK lately, is no bound at all). If the PM comes in, and says “this is my six year old son, I’d like him to be PM”, the monarch is entirely free to say “tough luck”. Or, if May came in, and said “Here’s one Farage, call him Nigel and I want him to be the PM”, if you want a less incredible claim.

So basically your complaint boils down to “the EU claims to be run by rules, but has no rule for the ECP selection before being presented to the EP, and hence is undemocratic”.

The democracy of the ECP is in the fact that they have to be approved by the MEPs. If the Council keep coming up with dumb candidates, MEPs are free to throw them out.

And, for most parts, the horse trading that’s going on is what tends to happen in most, if not all, of the continental parliaments and governments, where the parliament isn’t just rubber stamp machine for the government, but actually has some checks and balances.

So when we cast our votes, be it for Head of Government / Head of State (i.e. the Council) or for a member of the European Parliament none of us can tell who, or by what process, they will select the President of the Commission?

The fact that the European Parliament gets a veto tells us nothing about how the Council (or maybe the European Parliament — who knows, it’s a complete lottery) selects the candidates.

It’s like me voting for, say, the Conservative Party in the UK who then goes on to win an election. But then ending up with a Deputy Prime Minister who may, or may not, be from the Conservative Party, may, or may not, be selected by the U.K. Government or the House of Commons, and may, or may not have any public manifesto they stood on, selected on criteria which are not published anywhere and supposed to be based on a law, but that law isn’t interpreted by a court, but by politicians?

Alright-ey…

And the Monarch has not in living memory (or beyond) intervened in politics. Strenuous constitutional efforts are made to prevent this ever being necessary. But ultimately that is the monarch’s role in the setup of constitutional monarchy which is in place. And if I don’t like it, I can form a party dedicated to having a Republic and try to get myself and enough representatives elected.

Explain to me again how I can vote for either a candidate for the European Parliament or a particular Head of a Government via the usual system in the U.K. for choosing a Prime Minister and have either (or both, whichever it is supposed to be) select a candidate for the President of the Commission who might adhere to policies I wish to see enacted.

There is no such explanation available. You can’t appy democracy to backroom deals.

Arguably backroom deals, which is just another word for compromise, is how a system of representative democracy is supposed to work. As part of the electorate you may vote for a candidate who is going to represent you within the decision making processes. As a voter you neither get to decide on questions of personnel (Chancellor, PM, President of the Commission, Undersecretary for Beekeepers and related questions…) nor on specific laws. Referenda about important issues already break that mold and are part of the direct democracy toolset.

How the specific voting system works, majority, proportional or a mix is certainly up for debate but the idea is always to select someone who is going to make the decisions for you – not to select a programme for an automaton to execute. Therefore if you think the President of the Commission is such an important topic you would have to select a candidate who is going to use their power to your liking in that particular question if elected.

“It’s like me voting for, say, the Conservative Party in the UK who then goes on to win an election. But then ending up with a Deputy Prime Minister who may, or may not, be from the Conservative Party, may, or may not, be selected by the U.K. Government or the House of Commons, and may, or may not have any public manifesto they stood on, selected on criteria which are not published anywhere and supposed to be based on a law, but that law isn’t interpreted by a court, but by politicians?”

That is exactly that pretty much all not-two party systems work. Yep. So, if you consider a two party “winner takes all” system the only democratic one, then I can see how you have a problem with it (as a side note, there’s no law about SPK, apart from “should be considered”, which is pretty weak).

But you know, most of the other people consider it perfectly normal that it takes more than one party to govern, and thus compromises will be made. And that may well mean that the party you voted for, and even won, will be unable to enact the policies you wanted, and has to put into government other people that you’d like to see there. In the worst case, you can even see a “Grand Coalition”, where the party you voted for, and their theoretical life-and-death opponents put a government together. Stil, I didn’t notice people in Germany would consider it massively undemocratics.. They even voted for the same parties again, and they did the same again.

So again, your issue is that the EU system is not the british system, and hence you see it as undemocratic, and I guess would, on the same grounds, consider pretty much all continentals undemocratic.

@Mark – also, the SPK for most of the parties (via their EP factions) were, if I remember, well known in advance. So if you voted for a party A, you knew that they would be trying to put Mr/Ms. X as ECP.

@vlade We’re obviously in agreement :)

I’ll just add that, while I don’t have a strong view on that, the orthodox thinking on the French left has always been that a direct vote for the leader of the country was unwelcome and the first step to tyranny. That’s obviously rooted in the Napoleonic (and Gaullist) experience when “populist” leaders used the legitimacy of a direct vote to ensure their absolute power. That’s why the far-left is adamant that we should get back to the parliamentary system of the 3rd republic when PM were always put in power after “back-room” arrangements by leading political parties (and were often deposed and replaced by changing coalitions in the Parliament).

@vlade

That’s, surely, why we have Spitzenkandidat? Or at least, we were supposed to. That’s what everyone thought we’d be getting — so that everyone knew that, in the inevitable multi-party carve-up, the President of the Commission would be the leader of the largest grouping?

But no, there’s some other system which the Council has in mind. That it won’t share with the rest of us… but looks suspiciously like the Old Boys Network which is so derided in the UK? Certainly, it doesn’t look like Weber’s face fits. Not with those who matter, anyway.

Or is it just silly old Brits, “not understanding how these things work”?

@Clive – the point is that SPK is a recommendation (and a clearer one than what was there before). But not a decision.

Council chooses the candidate, EP has to approve it. Which creates a tension and checks+balances between council (executive) and EP (legislative).

Neither Council nor EP holds the upper hand here, and there have to be negotiations (aka horse trading) to get a result.

In general, it’s felt that negotiaions and compromises are good. It’s not always the case, but, as someone else pointed a long time to me, the main point of a working democracy is to slow things down to avoid rash decisions (see Mytilenian Debate). Not necessarily best in crises when time is short, but outside of that works pretty well IMO.

An addition on SPK – SPK is basically the EP saying “these are the candidates that have strong support from the parties and will not be problematic for factions”. But even the largest faction may not have enough to get their candidate installed, even if Council makes no problems.

Put the Council in, with the EU elections run at a different cycle to national elections, it’s entirely possible for the Council to be full of people who would have lost elections at home if held, and fundamentally opposed to the parties elected to the EP.

But, in the end, if the Council (and/or EP) would be full of EU sceptics, the EU would be on its last legs anyways, so the assumption is that the Counci/EP does want to make a deal at last. So this is the process to get them talking to each other.

@vlade

Back to the backroom we go, then. Or, rather, the Council goes. We don’t get a look-in. The Council proposes a selection, or the European Parliament proposes a selection, each does nothing more than trades horses. No public debate. No democratic oversight. When its all been stitched up, a choice of President of the Commission “emerges”. A bit like Popes.

The TFEU had, therefore, precisely zero effect. It’s hard to not be cynical about the real, observable, practical effect of this, and so much other, EU “reform”.

It’s no wonder the UK got uppity. There is no way this is going to work or ever was going to work for the UK mindset. De Gaulle was right all along ! Who knew…

I’m afraid it’s the same for me. The EU is very, very far from perfect. But from this side of the Irish Sea, the UK itself presents as a centralising state that has spent the last three centuries attempting quite successfully to disarticulate, dissolve and assimilate the non-English peoples of these islands into a uniform identity that more often than not elides Englishness and Britishness. And the pace and manner by which it has reformed its own governance structures has often left a lot to be desired. But I accept the view from England will necessarily differ.

Yes, I think the perspective from a small country (or peripheral region of a larger country) is very different than from a major country – this leads I think to the complete incomprehension many people, whether right or left wing – have towards the specific type of anti-EU expressions we read from the UK or Germany or France.

If you live in a small country, or somewhere like Scotland or Catalonia, you know you are dealing with a hierarchy of power structures, whether you want to or not. If you don’t voluntarily join or form alliances, you’ll be forced to do so. From the perspective of those, even a very imperfect EU is much better than the alternative – either dealing with direct power implementation from a neighbouring country, or an uncaring and uncomprehending central government ignoring peripheral regions.

The EU, for all its faults, is a rules based organisation, and that makes it far more accessible than many national governments. Its very lack of ‘democracy’ can paradoxically make it less prone to industry gaming – witness the imposition of worker safety, environmental, animal health and food safety regulations at a level far in advance of what most individual EU countries would dream of implementing on their own.

This describes no federation ever – Outside the United Kingdom, countries have what’s known as Constitutions that specifically stops that.

You mean like what they did in the Lisbon treaty?

I have never understood the weird fixation from British people on this point – But in any case you should be aware that, the commission has become less powerful, and more importantly, that it’s the council that in practice directs policy.

First, any suggestion that reads ‘more like the UK system’ is wholly bad – I would rather import constitutional practice from North Korea, It’s at least from this century – Second, you seem unable to understand that the EU is a Federation, and thus, the council (of ministers) is a legislative body, representing the states, think the Senate of the Bundesrat, not an executive body.

It’s impossible for ‘true power’ to reside in one place in a functioning federation – That’s actually the definition of it.

The EU doesn’t have a police, secret or otherwise, it doesn’t have an army, and it controls 1% of the GDP of the EU – There is no basis whatsoever to think ‘Tyranny’ is incoming, and if you think so, you clearly must be living in perpetual terror as the Westminster system lacks any protections from Tyranny – It being a majority vote away whenever they feel like it.

If you can tell me where I can cast my vote for the President of the Commission, I have my pen in hand, ready to mark my ballot paper. But while you’re at it, can you tell me any other notional democracy where the civil service gets to make policy?

If the Council is the legislature, what’s the European Parliament supposed to be there for (I’ll do my best not to retort “provide democracy window-dressing” but I’ll probably end up failing).

Ahh, yes, tyranny. We like to think, don’t we, because it’s so comforting, that we know what tyranny is, what it’s not, and that we’d not only recognise it if we spotted it but we’d be able maybe to do something about it if it threatened to emerge. And if it did emerge, it would do so suddenly, all at once. Or at least fairly quickly.

I’m not so sure. I don’t know if you are familiar with the details of the Chernobyl accident. The operators of the plant abused their technology, did dangerous things they knew, or should have known, were dangerous. They deactivated failsafes. They ran the reactor outside of normal parameters. They took huge risks.

When I cast my beady eye across the channel, I see a lot of EU Member States doing an awful lot of potentially catastrophic things with their civil societies. Their democracies. Their haphazard attempts at statecraft. I wonder to myself, how can they not see what they are doing? Why do they not appreciate the damages which could result?

When I show up with my wary and fretting musings on very progressive, enlightened places (like this one, for example) a lot of very bright people, far cleverer than I, tell me that, oh, don’t you worry your pretty little head about that Clive. The EU will stop anything really bad happening. If there’s anything that starts to get out of hand and threatening tyranny, we’ll simply have to press the “EU” safety button. That’ll sort everything out. Don’t you witter on, you’ve got bigger problems by far with Brexit.

This notion — the immutable certainty that the geopolitical equivalent of the AZ-5 button can always be pushed if things gets really sticky — was what led the managers of the Chernobyl reactor No. 4 to lull themselves into a reckless and unfounded sense of security. When they hit the AZ-5 button thinking that, oh, heck, it’s all gone horribly wrong but never mind, we’ll just SCRAM the core and all will be well again, they unleashed forces they had no idea were there and had no idea would manifest themselves in that way.

I so admire your unshakable confidence in your EU AZ-5 button. I understand why, having seen it blinking its nice, reassuring little lamp on the control panel, you think that if things get pushed to the limit and beyond, the EU control rods will lower and no matter how hot it is, it’ll all get cooled down calmly. No nasty outbreaks of dangerous tyranny. I wish I could share it. But not only do I not, I think that what seems to be a guarantee of safety might — just, possibly — cause a runaway reaction and a big explosion and release of tyranny one day.

Time, as always, will tell.

The fact that they can all vote for their PM will be news to many UK citizens.

(sorry for the snarky remark, I really have trouble following your points…)

Maybe you’re not really trying.

I can vote for the UK Prime Minister, you can vote for the French President. I’m with you there. Then the Heads of Government or Heads of State trot up to the EU Council. Which “chooses” the President of the Council. Please explain to me by what democratic process does this occur?

Is it Qualified Majority Voting — each Member State votes for a particular candidate and the votes are realigned to take into account the population of the Member State in question. Nope.

Is it one Member State, one vote? Nope, not that either.

It is, rather “I’ll support your candidate for, [say], the ECB Head, you’ll support mine for the President of the Commission”.

And just who are the candidates, anyway? Did you get to pick them? Nope, me neither.

But you are still attempting to tell me that all this is just hunky-dory and I should not need to be troubling my spell checker to look up the words “democratic deficit”?

I recall you are a Labour voter. Pray tell how you or any non-Conservative party member has any say in the current PM contest. And you don’t choose the PM. Look at the process by which May was selected. You only choose the party and if your party or your party coalition wins, it then chooses the PM.

For the U.K. Labour Party, the leader (and so any Prime Minister in the event that the current leader vacated such as if they chose to step down or dies in office) is chosen by the members in a one member, one vote system. The Conservative Party has a different system, but if the people don’t like the Conservative Party and how it picks its leader then they shouldn’t vote for the Conservatives. If people find that now they want a different way of a party picking its leader (who will become Prime Minister) then in two years from now (and no more than five years, if this had happened in 2017) there must be an election and they can vote for a different party with a different system for picking the leader and thereby the Prime Minister.

And the corollary of saying that if a party changes its leader we have to have a public vote is that, should a Prime Minister die in office, there has to be a general election. This would render any older or less than obviously stellarly healthy leader less electable — either as party leader or as a potential Prime Minister. Theresa May got enough unjustified flack for her having diabetes.

Conversely, whether we get a different system in the EU is not under our democratic control, as the current chicanery https://www.theparliamentmagazine.eu/articles/news/battle-european-commission-presidency-reaches-fever-pitch shows. The European Parliament cannot overrule nor enforce the Spitzenkandidat system. The Council can do backroom deals to try to short circuit it, but it is a stretch to call that direct democracy. And Spitzenkandidat may prevail anyway, regardless of what any particular Member State Head of Government or Head of State on the Council might think (or think their electorate might want).

The president of the commission, is in effect the prime minister of the European Union, selected by the head of state (The European council, the heads of government of the member-countries), subject to commanding the confidence of the European parliament. he/she/they are not civil servants. They employ civil servants.

As for the dual chamber system the EU uses, that is in fact very very common in federal systems, where the lower house, the EP represents the people (all 510 million) whereas the Council of the European Union, (council of ministers), represents the constituent states.

There is no ‘The’ legislature, there is several, again, a core part of being a federation.

As for tyranny, I did not say that the EU was immune from becoming a tyranny, I said it was impossible for the EU to exercise the required powers of a tyranny, since it lacks the means to enforce their will. Imagine if you will the Soviet Union, absent the Red army, the KGB, 90% of it’s budget – Josef Stalin times a thousand would not have been able to enforce a tyranny.

Or to put it into the context of a nuclear reactor, The EU doesn’t have a nuclear reactor to blow.

Let’s say I stand for election to the European Parliament, promising to form Clive’s EU Makeover Party grouping in the European Parliament. I am, as you would expect, wildly popular and get elected as an MEP. Other MEPs flock to my new grouping and I am easily the leader of the largest single group in the European Parliament, not an outright majority but, let’s say I have the backing of 40% of the MEPs who join my grouping. I also secure another 10% from a radical coalition in the left who won’t join my group but will vote me in as President of the Commission. I am, naturally, eager to, erm, make a few changes.

I traipse down to see the President of the Council and say that under the clauses in the TFEU, I expect my Presidency to be confirmed as a formality by the Council. Not only because I command leadership of the largest group, but that I can also get approval from the European Parliament itself.

Oh, no, very sorry, I’m told, the Council won’t wear it. They have “concerns” about my “lack of experience” “leading” an institution as “complex” as the Commission. They’d got their own candidate in mind and they’re going to “advise” the Parliament who they can vote for. And to not let the door hit me on the way out.

But, I say, aghast, what about the TFEU, which required that the Council “take into account the Parliament”? Yes, says the President of the Council, what about it? And why am I still here, can’t I hear a “sod off” when someone tells me to?

This is a humourised version of what is happening right now, as we speak.

And this all passes your smell test?

In theory, I sort of agree with a number of your points. But I also believe that you’re ignoring a massive problem with “choice will be ours”. The choice is ultimately very much limited by the environment you’re in.

The environment now is such that the UK is not entirely a bit player, but not a first class player either. So it will find itself on the side it didn’t see itself for hundreds of years – being pushed (openly) around by the first class players (which includes the EU). That is, and has been, the fate of countries that border first-class players, for better or worse.

Ultimately, the UK will have to hitch its wagon to someone (because it has to trade, and trade with the non-first class players is not enough to support it, by far). Sure, the EU choice is bad. Is the US or China choice any better, really?

This is mostly the bit that put me (quite firmly but not without consideration) in the remain camp. That, and the free movement of peoples :-)

Default is a done deal this Halloween. The buyers of Brexit and other nations of Europe were given that time to mentally prepare. Also the final hammer on the 2010’s business cycle. Which is already ending.

This post is so meaty to me that I couldn’t stand reading it in full before commenting. My comments are on the openness and control issues. First, it should be noted that since the referendum things have changed in the international order in a radical way. From being poised to strengthen the Intl. Neolib Order through those TISAs, Trans Oceanic Partnerships etc. we have gone to the open commercial confrontations –please, don’t say wars– of today. Looks like the UK is building a protecting fence limiting exchange with her neighbours while at the same time trying to open as many gates as possible with distant countries. It is doing so in an unstable environment in which “WTO rules” are in jeopardy. Whether this is wise or not will be seen sooner or later.

Another point that I find striking is under the Fairness point. This phrase got my attention: Although… there is little evidence that reduced EU migration is boosting pay growth at the bottom end that goes well against conventional economy wisdom regarding migration and wages and should be discussed in greater detail (not only in the UK case but as a general case).

The EU not on the way of a tyranny?

How far from it?:

https://jacobinmag.com/2019/05/european-union-parliament-elections-antidemocratic

Can the State of Texas, make a democratic choice and ban abortion i wonder?

I have an issue with the implicit definition of “openness” here. Unfortunately, economists think that openness is restricted to the free flow of capital, goods and services. A more open definition of openness should include the free movement/stablishment of people –evidently in this regard openness will be reduced in the UK– and the last part of openness should include sharing a legal/political framework and in this case the UK also goes in the direction of closeness. As an aside, we have learned that there are already trade offs between economical openness and control. For instance, vlade and PK have repeatedly said here –and I agree– that a relatively small economy (compared to giant economic blocks such as EU, US or China) has a relatively low level of control in, for instance, monetary or fiscal policy compared with such err.. commercial partners.

Thanks Clive – both the essay and the comments. Masterful.

The appreciation should go, I think, to the excellent and endlessly stimulating commentariat we are lucky enough to have here. It really is the best, anywhere.

Growth over the last 30 years in the EU?

Zero. In real terms GDP growth is back to where is was pre EU. The damage done to UK business has been immense. The neoliberal plan of the EU is in tatters, held together by cheating on the “rules” and depressing the economies of Italy, Greece, Portugal etc. Infrastructure is falling apart to the degree that some bridges are unable to carry heavy traffic. The railways are in an appalling state, particularly in the UK which boasted one of the best in the world. Inequality is greater than any time before the Great Depression. The South of Europe has generations which have never, nor will ever, have any meaningful employment. Housing ownership is at it’s lowest level in living memory. Monetary union is a neoliberal wet dream, failing to deliver the stated benefits and is now managed by a bunch of unelected technocrats. Even the dream of the common market has been destroyed by the plethora of rules and subsequent treaties that are amended and breached at will unless it happens to be Italy or Greece – watch that space!

Can anyone give any compelling reason why the UK would want to stay in this mess?

This wishy washy examination of the real to the UK social and economic well being is narrow and completely without any basis in fact. How does the freaking sterling exchange rate have anything to do with any of the objectives of this report? The doomsayers are wrong and now in full retreat but still denying the obvious. Get out. It won’t be easy but the UK Government has all the economic tools to ensure UK citizens and business will be better on the other side of this disaster. How many of these unnamed “experts” are aligned with the remainers?