By Shannon Monnat, Associate Professor, Syracuse University. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

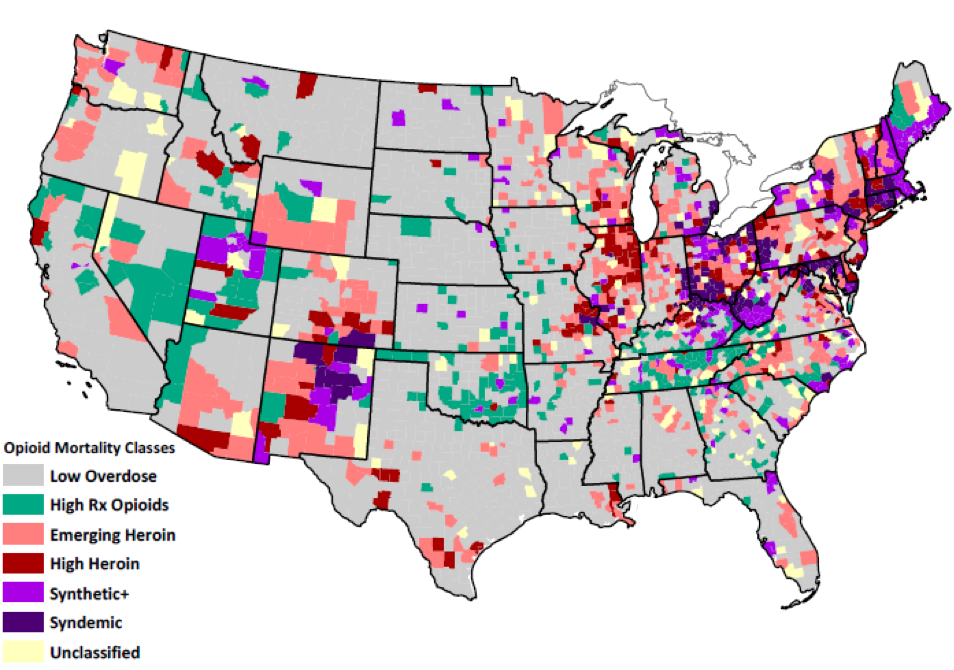

Over 400,000 people in the U.S. have died from opioid overdoses since 2000. However, there is widespread geographic variation in fatal opioid overdose rates, and the contributions of prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl) to the crisis vary substantially across different parts of the U.S. In a study published today in the American Journal of Public Health, we classified U.S. counties into six different opioid classes, based on their overall rates and rates of growth in fatal overdoses from specific types of opioids between 2002-04 and 2014-16 (see Figure 1). We then examined how various economic, labor market, and demographic characteristics vary across these different opioid classes. We show that various economic factors, including concentrations of specific occupations and industries, are important to explaining the geography of the U.S. opioid overdose crisis.

Figure 1. Fatal Opioid Overdose Classes by County Note: Classes are based on absolute fatal overdose rates in 2014–2016 and the change in rates between 2002–2004 and 2014–2016. Analyses included 3,079 U.S. counties.

There are Multiple Geographically Distinct Overdose Crises in the U.S.

There is not one universal opioid overdose crisis in the U.S. There is significant geographic variation in deaths from prescription opioids, heroin, and synthetic opioids. Most counties (58%) had low or average fatal opioid overdose rates and rates of change from 2002-04 to 2014-16. These low overdose counties are distributed throughout the southern and central U.S. and California. Nearly 9% of counties had high overall rates and high rates of growth in prescription opioid overdoses. High prescription opioid overdose counties are concentrated in southern Appalachia, eastern Oklahoma, parts of the desert southwest, Mountain West, and Great Plains.

High heroin counties (5.4%) and emerging heroin counties (14.5%) are geographically distinct from the prescription opioid counties and are concentrated in parts of New York, the Industrial Midwest, central North Carolina, and portions of the southwest and northwest. There are two classes where large shares of deaths involved multiple opioids, including fentanyl. The synthetic+ class (6.9%) has high and fast-growing fatal overdose rates from synthetic opioids alone and synthetic opioids in combination with prescription opioids and to a lesser extent, heroin.

Counties in the other multi-opioid class (4.2%) are in the depths of the opioid crisis, having very high and rapidly-growing fatal overdose rates from all types of opioids: heroin, prescription, synthetic, and combinations of the three. We term this class the “syndemic opioid class” because it reflects multiple concurrent or sequential epidemics, in which the combination of high overdose rates from multiple opioids greatly exacerbates the crisis. The synthetic+ and syndemic classes are concentrated throughout New England, central Appalachia, and central New Mexico.

On average, low overdose counties are less white and more rural than any of the high overdose counties. However, rural counties are most heavily represented in the high prescription opioid class; 73% of counties in the high prescription opioid class are rural compared to 35% in the syndemic class.

How are Economic and Labor Market Factors Related to the Geography of the Multiple Opioid Crises?

Fatal overdose rates are higher in counties characterized by greater economic disadvantage, more blue-collar and service employment, and higher opioid prescribing rates. High rates of prescription opioid overdoses and overdoses involving both prescription and synthetic opioids cluster in more economically-disadvantaged counties with larger concentrations of service industry workers. High heroin and syndemic opioid overdose counties (counties with high rates across all major opioid types and combinations of opioids) are more urban, have larger concentrations of professional workers, and are less economically disadvantaged.

High blue collar and service worker presence – what we might think of collectively as the “working class” – were associated with increased odds of being in all five of the high overdose classes versus the low overdose class. The nature of blue collar and service work might increase risk for work-related injury or physical wear and tear, thereby increasing demand for pain treatments within these contexts. Moreover, as shown in numerous in-depth accounts (Quinones, 2015; Alexander, 2017; Goldstein, 2017; Macy, 2018) declines in good-paying and secure employment for the working-class over the past four decades have manifested in collective psychosocial despair, population loss, family and community breakdown, and increased substance misuse.

Consider the cases of McDowell County, WV and Scioto County, OH, which are classified in our study as a high prescription opioid overdose counties. For several decades, McDowell County, West Virginia was the world’s largest coal producer, but McDowell has experienced massive and sustained population decline from 100,000 in 1950 when coal jobs dominated the area, to about 19,000 today (Pilkington, 2017). As coal declined, lower paying precarious service jobs became the main source of employment, but even those have disappeared. Even Walmart couldn’t make it there; it closed in 2016. McDowell now has among the highest prescription opioid overdose rates in the U.S.

A similar story unfolded in Scioto County, Ohio. In Dreamland, Sam Quinones (2015) wrote extensively about the city of Portsmouth, located in Scioto County. Portsmouth is blue-collar community with a once thriving manufacturing base anchored by shoe, steel, brickyard, atomic energy, and soda factories. By the 1990s, these factories were long gone, replaced by big-box stores, check-cashing and rent-to-own services, pawn shops and scrap yards, and the nation’s first large “pain clinic” where doctors doled out prescriptions for OxyContin and other narcotics like candy. Portsmouth was soon the pill-mill capital of America, with more prescription pain relievers per capita than any other place in the country. Today in Scioto County, incomes are lower than in the 1980s, and poverty, disability, and unemployment rates are all high. According to the latest Census data, 39% of prime working age males (ages 25-54) in Scioto County are unemployed or out of the labor force altogether.

McDowell and Scioto counties were among the canaries in the coal mine for the first wave of the opioid crisis that began with prescription opioids. Pharmaceutical companies capitalized on and exploited the underlying vulnerability to opioids in these places—drugs that numb both physical and mental pain. Interventions aimed at addressing the overdose crisis in places with large concentrations of blue collar and precarious service employment must consider the likely absence of alternative pain treatment services, underfunded public services resulting from community economic disinvestment and population loss, and the need for programs that address not just drug addiction but underlying chronic pain, trauma, and despair.

Ultimately our study suggests that national drug policy strategies, especially those that focus on specific substances, will not be universally effective across the U.S. For example, supply-side interventions targeting opioid prescribing are unlikely to be effective in places characterized by high rates of heroin and synthetic opioid overdose. It is also clear that economic factors matter for understanding the geography of the opioid crisis, and these are getting far too little attention from policymakers. Without attention to place-based structural economic and social drivers of the opioid crisis, supply-side policy interventions are unlikely to have any real sustained impact on reducing rates of drug addiction and drug-related deaths.

Alexander, Brian. 2017. Glass House: The 1% Economy and the Shattering of the All-American Town. St. Martin’s Press.

Goldstein, Amy. 2017. Janesville: An American Story. Simon & Schuster.

Macy, Beth. 2018. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America. Little, Brown, and Company.

Pilkington, Ed. 2017 (July 9). What Happened when Walmart Left. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jul/09/what-happened-when-walmart-left.

Quinones, Sam. Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic: Bloomsbury Press; 2015

Chilling.

I live in one of the pink “Emerging Heroin” counties. The local economy is driven by a small class of Silicon Valley commuters and beach day-trippers, but is otherwise still largely agricultural, worked by migrants. The zombie/urban-outdoorsman population tends to be older, white, and transient.

Our transient and migrant populations are classic representatives of Lambert’s Two Laws of Neoliberalism: “1) Because markets! 2) Go Die!”

It’s become evident to me that many middle-aged men and women have simply given-up on trying to sustain the constant hustle of the Gig Economy, and heroin and speed ease the burden of living rough. Many migrants can only make a decent living by hustling in the purest marketplace of all — and their side-hustle has become so diffuse that there is no “Mr. Big” to take down. Our town has become known as a good place to score dope and camp out.

It’s Whack-a-Mole for the social services and the police. The locals have simply thrown up their hands; they can’t put a checkpoint at the county line…

Yes, no checkpoints. And that is the point of the article, I believe. We need an effective NATIONAL policy (and monetary commitment) to turn the ship of Despair. While many of the homeless have real physical and mental disabilities that make living efficiently in a complex society very difficult, living rough is not a choice; it is a predicament. To halt the Decent into Despair will require housing, health care, and a real jobs program (GND?) and less saber rattling with Iran. The lack of joy in American society is palpable.

Mr & Ms Bigs in great profusion. If their names weren’t chiseled into half the marble museums, galleries and concert halls on this island? I remember, since my home town’s Mr Bigs were outside Youngstown and Greensburg; nobody told them, they were supposed to step on dope. It was nothing to have folks keel right over, waiting to buy a carton of kingsized Hershey Bars. Now, that tiny Pittsburgh is about equal with giant Philly & NYC in total opoid deaths, that dope was coming from Tobyhanna, not TO & Trump’s mercenaries are basically bragging about being “kings of all Kafiristan,” and Iranian poppies seem to right up there with pomegranates, pistacios and plastics. Opoids are the religion of the proletariat?

The pockets of heroin use in northeastern WA state along the Canadian border are in counties that are struggling economically, the map also suggests that the heroin might be entering via Canada. Just north of the border above NE Washington state there are a lot of Canadian cannabis farmers, I wonder if the heroin use is similar there? Vancouver has long been an entry point for Asian dope, and the city itself has had a bad heroin problem for many years. I don’t know why Canada doesn’t just legalize the heroin so that the criminal element would be cut out of the picture. The trade has been going on for so long that I can only assume that someone is on the take.

I was unsurprised by the blocks of pain labeled under the colors of emerging heroin and synthetic+ overdoses in the Western WA tri-county area from Everett/Snohomish to Seattle/King all the way down to Tacoma/Pierce counties. Not to mention that large fan of emerging heroin opening west through Kitsap, Mason and Grays Harbor counties (predominantly Trump Country).

Some Seattle locals are in a lather, heaping blame and scorn on the homeless population under the false assumption that all homeless are drug abusers. Many Seattlelites believe people are homeless simply because of addictions. They fail to see the full extent of the problem——both of homelessness and drug addition—–or how the two are largely mutually exclusive.

This map shows how the two scourges are independent of one another with some overlap. Many of the afflicted counties in Western WA don’t have an eviction epidemic that is the underlying cause of homelessness in the Seattle area. They do fit the profile of “…places with large concentrations of blue collar and precarious service employment…”.

Also not surprised that “policymakers” are ignoring this situation. Their big money donors are glad that masses of people are pre-occupied with drugs and despair. Otherwise they would be pushing back against the current regime of privitization and looting.

A lot of stuff transits in through the port of Vancouver, there’s a good amount from the of port of Seattle, too. 93% cartel production, ie tar is the rule, and not brown powder.

Heroin seizures in Vancouver numbers and smuggling methods detailed here

http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2012/sp-ps/PS4-122-2012-eng.pdf

Not 100% applicable, but some interesting stuff in this about super high purity cocaine being shipped into the port of seattle, cocaine isn’t talked about often these days but it can be even worse for a town than heroin, because if you get hooked you have the energy to get up to anything

https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-11/DIR-032-18%202018%20NDTA%20final%20low%20resolution.pdf

You want to launder 400,000 dollars you got by selling heroin in portland? Why not invest in garment wholesalers in los angeles?

https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2019/04/09/federal-investigation-portland-drug-trafficking-organization-reveals

There’s so much good info with lots of juicy juicy FACTS that’s easily accessible, I don’t know why the internet is so dominated by the same 3 outlets saying things everyone already knows. Thanks for being the exception, NC!

In 2008, a 3 letter government agency had a hostile takeover of coke and pot drug distribution network based out of Memphis. This network distributed in the area of upper midwest, chicago, detroit, Indianapolis, detroit etc. You can see the heroin areas match up with this. The government agency tried to co-opt the head of distribution network, he said no, then he was removed shortly thereafter. When I first heard this story it was shocking, but seeing data in maps that supports the story makes it the more believable. All of this was no accident.

Was it like the CIA’s cocaine shipments for the Contras? If you have any links, I would be thankful.

On the CIA’s record of involvement with drug traffickers, try the essay “Pipe Dreams,” available online, by my genius researcher friend Daniel Brandt, with some light “literary” editing of mine.

400k!

Is there anything like the AIDS quilt for these victims?

Yves:

I had written more about the opioid crisis here: Opioid Use since 1968 and Why It’s Abuse Increased. Why is this so different than other posts of mine and other information found?

There is a time line from 1968 till 2015 showing complete data on the number of deaths due to Opioids and drug overdoses. This was important because you can tie when the Jick and Porter letter to the NEJM, the numbers of increasing citations of that letter in a bibliometric analysis from 1980 onward to 2017, the introduction of Purdue’s Oxycontin in 1996, and the increasing number of deaths after from 1968 to 1996 (when Oxycontin was introduced).

The data is pulled from my own research and the US Senate Joint Committee study The Rise in Opioid Overdose Deaths. They too have an interactive US map and a breakdown by state of the growing numbers of deaths.

I tied this together in my post at Angry Bear. Things are starting to get interesting as I am being asked to be a technical writer on healthcare for a media event. We shall see.

New York City would be fun this weekend. Too late for me though. I would also have to bring my own bottle of bourbon similar to the likes of some one else; “Take it from me, there’s nothing like a job well done. Except the quiet enveloping darkness at the bottom of a bottle of Jim Beam after a job done any way at all.” More into Basil Hayden.

I can not imagine NYC shy of you as you migrate to the South. That will be a rude awakening for them. Safe travels and best of luck.