By Nicholas Shaxson a journalist and writer on the staff of Tax Justice Network. He is author of the book Poisoned Wells about the oil industry in Africa, published in 2007, and the more recent Treasure Islands: Tax havens and the Men who Stole the World, published by Random House in January 2011. He lives in Berlin. Originally published at Tax Justice Network

The Finance Curse is a concept first developed by the Tax Justice Network. It is a relatively simple idea — and also an original and powerful multi-level critique of the modern global economy.

Here we frame it in a number of different ways.

1. Shrink Finance

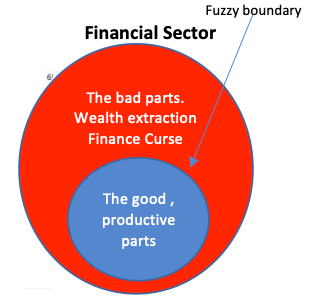

We all need good finance. A financial sector has a useful core surrounded by a toxic, predatory part. This should be entirely uncontroversial, especially following the global financial crisis.

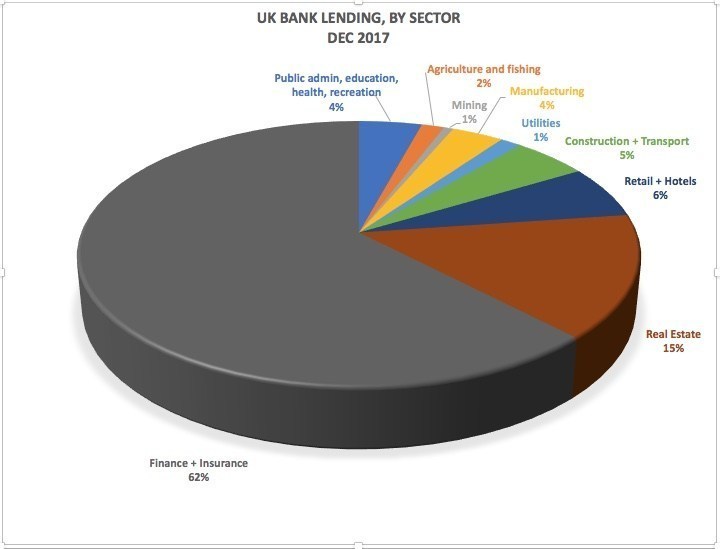

It seems sensible, then, to shrink finance down to its useful core. A fast-growing strand of academic research, known as Too Much Finance, backs this up. Here’s a startling picture from the real world, illustrating the excess bloat (source.)

2. Wealth Extraction vs. Wealth Creation

This is closely related to Point 1. The bad part of finance is engaged in predatory wealth extraction, as opposed to the good part, which supports wealth creation (and other socially useful ends.)

This has geographical dimensions, as well as racial, gender, disability-based, and others. The most privileged interests profit from wealth extraction, while the least privileged tend to be those being extracted from.

Other terms that have often been used in this context: Makers vs Takers; Producers vs. Predators; there are various other terms, some less pleasant.

This framing provides exceptionally rich research material, into the many different mechanisms of financial wealth extraction.

3. Cuckoo in the Nest

“The City of London likes to portray itself as the goose that lays the golden eggs. In reality it is a different bird: a cuckoo in the nest, crowding out and killing other sectors that could have made Britain more prosperous.”

(The quote is from The Finance Curse book, which lays out some of the many ways in which this happens.)

This highlights the damage that oversized, extractive finance inflicts on other parts of the economy, crowding out other sectors. This, too, has geographical, racial, gender, and disability-based implications, as laid out here.

Studies have sought to quantify the damage. Here’s one, estimating that the excess size of Britain’s financial sector inflicted a massive £4.5 trillion cumulative hit to British GDP from 1995-2015, which includes the period of the great financial crisis. It explains:

A similar calculation for the United States estimated a $13-23 trillion hit to the United States from 1990-2023. These costs are due to misallocation of resources, excess “rents” due to the financial sector, and financial crisis.

4. The Tax Haven Comparison

Tax havens are financial centres that transmit harm outwards, elsewhere, offshore, to other countries. It harms foreigners: “This hurts them.” The Finance Curse, by contrast, transmits harm inwards, to one’s own country. “This hurts us.”

If we’re worried about helping low income countries, this is an especially useful frame, because it’s relatively hard to get governments or citizens to support (apparently) altruistic actions to help foreigners, or to engage in complex international collaborations to counter a race to the bottom.

It’s far more powerful to rally people behind a platform that caters to national self-interest. Shrink predatory global finance, not only to ‘help them’, but to ‘help ourselves.’ (In the process, this will help victims in other countries too.)

This also helps clarify the boundaries of the finance curse concept. Tax havens certainly hurt or ‘curse’ people elsewhere, but that’s an extension of the core “this hurts us” concept.

5. The Resource Curse Comparison

The Finance Curse concept originally emerged from discussions between John Christensen, a former Economic Adviser to the British tax haven of Jersey, and Nicholas Shaxson, then an expert on the “Resource Curse” afflicting many countries whose economies are dominated by oil or minerals or natural resources. Likewise, the Finance Curse afflicts countries with a dominant financial centre.

The key misunderstanding around the Resource Curse is that these countries are poor because elites are stealing all the money. That does happen, of course, but the deeper understanding is that many of these countries are even poorer than if they’d never discovered any natural resources. It also leads to what’s known as “path dependence,” as other sectors wither, leading to a problem known as ‘putting all your eggs in one basket.’

As the “too much finance” literature shows, finance has similar effects.

There is a large overlap between the two “curses,” both in terms of the causes, and the effects: a similar “brain drain,” a “Dutch Disease,” recurring volatility and crises, rent-seeking (or wealth-extraction) dynamics, state capture by private interests, and plenty more. To understand more, see Section 1.0 here.

6. The Telephone Comparison

We need finance, but the measure of its contribution to our economy isn’t whether it creates billionaires and big profits, but whether it provides useful services to us at a reasonable cost.

Imagine if telephone companies suddenly became insanely profitable and began churning out lots of billionaires, and telephony grew to dwarf every other economic sector—yet our phone calls were still crackly and expensive and the service unreliable.

We’d soon smell a rat. All that wealth, and all those telephone billionaires, would be a sign of sickness, not health. (This analogy comes from here.)

7. The Paradox

Another way to frame the finance curse is to couch it in terms of an apparent paradox, which is is that more money or “too much finance” makes you poorer. This again overlaps with the Resource Curse above, sometimes known as the Paradox of Poverty from Plenty.

This also connects with the point that a large portion of finance is wealth-extracting rather than wealth-creating, as Point 2 outlines.

8. Financialisation

This is a term preferred by academics, which overlaps heavily with the Finance Curse. Different people offer different definitions: perhaps the best-known comes from Prof. Gerald Epstein:

“the increasing importance of financial markets, financial motives, financial institutions, and financial elites in the operation of the economy and its governing institutions, both at the national and international levels.”

Financialisation essentially involves two trends, particularly marked since the 1970s. First, the growth in size in the financial sector. Second, the increasing penetration of financial techniques, tools, and especially debt into different parts of industry, agriculture, caring professions, and many other parts of the non-financial economy, so that they increasingly resemble financial actors. This involves wealth extraction and is justified by the shareholder value revolution.

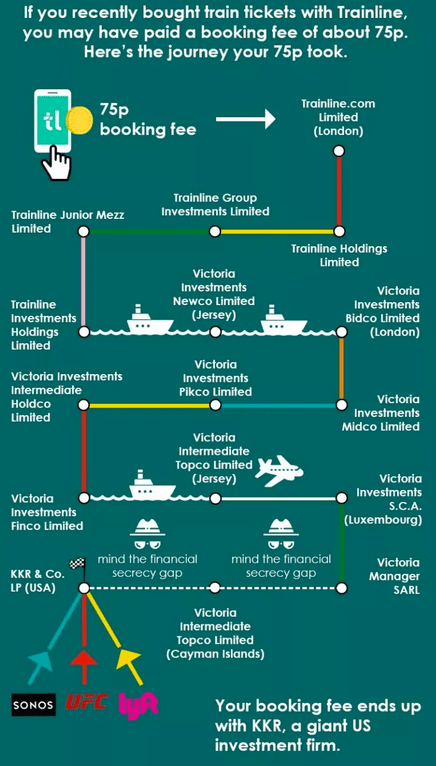

This infographic gives just one example of what the second aspect of financialisation looks like. A wealth-extraction pipeline.

9. Shareholder Value

From the 1970s, intellectuals led by Milton Friedman and Michael Jensen argued for that corporations should no longer be run for the benefit of a range of stakeholders (owners, employees, communities, taxpayers etc.,) but instead should have a single-minded focus on maximising wealth for owners.

This way of thinking encapsulates the ideology behind the giant shift towards wealth extraction since the 1970s. (The shift is described and illustrated in the Private Equity chapter here.)

10. Mafia

The supporters of “more finance” say that the financial sector creates large numbers of jobs, tax revenues, trade surplus, and so on. (For example, here.) For many if not most people, that’s the end of the story.

But one could make the same fallacious argument about organised crime. Mafia-owned businesses create jobs, pay taxes, contribute to exports, and so on. But that is not to say that the Mafia is a good thing. Ideally we want to keep the businesses, but take the Mafia out of them. Similarly, we want to de-financialise our economies.

(We’re not saying here that the financial sector is necessarily like the mafia, though parts of it may be. We’re merely making an analogy, to aid understanding.)

11. Net Versus Gross

This is another way to challenge the false claims about a financial sector’s alleged contribution to the economy that hosts it (such as those published by TheCityUK). These figures they like to put about represent the sector’s gross contribution to the economy.

But the gross benefits are meaningless when it comes to making sensible policy. We need the net contribution. That is, the benefits minus the costs of oversized finance. Here’s one publication that lays out the net contribution.

12. Optimal Financial Sector Size

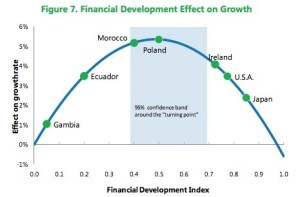

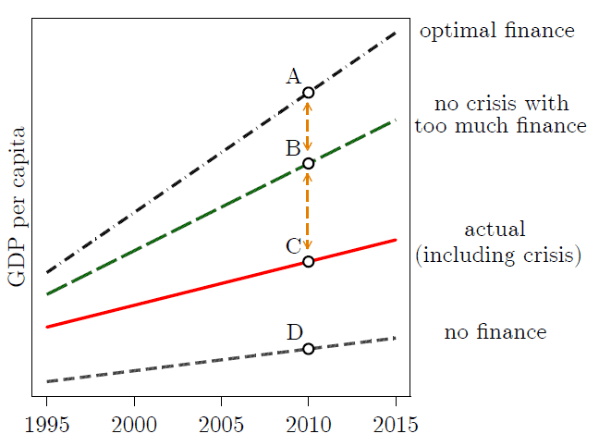

This is one of several graphs published by the IMF, the Bank for International Settlements, and others. The basic relationship is that a country’s financial sector has an optimal, growth-maximising size.

They recognise that if a country’s financial sector gets too big, it turns predatory and further growth in finance reduces that country’s economic growth. (For more such graphs, see here.)

This graphic, from finance Prof. Gerald Epstein conceptualises the difference another way.

Point D is where an economy would be if there wasn’t a financial sector: little more than subsistence farming. Point A is the optimal point where growth would be maximised, with an optimally sized financial sector serving its useful roles. Point C is where the economy currently is. (Point B is merely an effort to separate out the effects of crisis from other effects.)

For more on this, see here.

13. There Is No Trade Off: It Is Not Democracy Versus Growth

Many people labour under a misguided belief that there is a trade off between democracy and prosperity. As in: “If we tax and regulate finance and big business too much, we’ll lose jobs in the City of London and Wall Street.” Better give the capitalists freedom to do what they do best.

The Finance Curse shows us that there is no trade-off. If we tax and regulate the financial sector as democracy demands to curb predatory activities, the finance curse tells us that this shrinkage of the financial sector will make us more, not less, prosperous, as those studies in Section 3 suggest. This is especially true in larger economies. It’s a win-win.

This means that the Finance Curse carries an enormously hopeful, positive message.

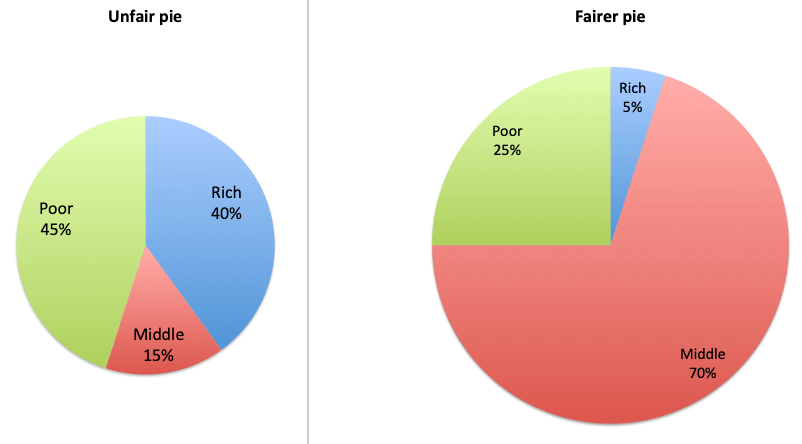

14. The Pie

This is closely related to the “No Trade Off” point above. Many people think that if we redistribute the pie more fairly, we’ll shrink the overall size of the pie, and it will discourage or frighten away investment.

The finance curse shows that this is incorrect. If we redistribute the pie more fairly by curbing wealth extraction and shrinking finance back to its useful core, we’ll grow the pie. This is the ultimate win-win.

The finance curse helps show why.

This links the finance curse to debates about inequality, and to another strand of researchshowing that more unequal countries grow more slowly.

15. Race to the Bottom

When one country enacts a secrecy law, a tax or financial regulatory loophole, or an environmental free pass, to stay ‘competitive,’ others may follow suit, to “stay in the global race.” A race to the bottom ensues. The result is ever lower taxes and rules and regulations on mobile billionaires and corporations, leaving the rest of us to pick up the consequences. This hurts both ‘us’ and ‘others’, overseas).

This is closely related to questions of “national competitiveness,” below.

16. The Competitiveness Agenda

This is a way to talk about the Finance Curse’s global dimensions, and how they hurt the country hosting oversized finance. It’s perhaps the most complicated concept to convey. We’re told our countries must ‘compete’ and be ‘competitive.’ We need a ‘competitive’ tax system and a ‘competitive’ financial centre. It sounds great! Motherhood and apple pie! Who wants to be ‘uncompetitive.’? This is a potent ideology.

But what do these c-words mean? Countries aren’t anything like companies, and the two forms of competition are utterly different beasts (to get a first sense of this, ponder the difference between a failed company, like Enron, and a failed state, like war-wracked Syria or Venezuela.)

National competitiveness can have many meanings, but the finance curse unpacks the most virulent strain: the Competitiveness Agenda, heavily associated with the now-discredited political movement known as the Third Way. In a nutshell, this agenda tells us to hand tax cuts, deregulation, tolerance for monopolies, subsidies, too-big-to-fail banks and big multinationals so they can compete on a global stage. In short, we must extract wealth from society, from ordinary people, and hand it to big banks and multinationals, so as to be “competitive.” The finance curse shows that this is insane. A more ‘competitive’ economy in this sense will increase the role and size of finance, which the finance curse tells us will reduce growth and cause other harms.

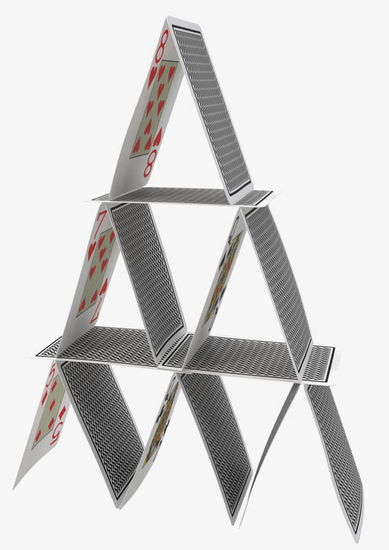

The whole Competitiveness Agenda is an intellectual house of cards, ready to fall. Understanding the Finance Curse and how to tackle it provides great hope and vision for the future.

Note: other c-terms include “Open for business” (which means ‘favouring handouts to multinationals.’) “We are in a global race.”

Further reading: the chapter on Charles Tiebout, here.

17. Unilateral Action Is Possible

A lot of people who want to “do something” about the race to the bottom focus on setting up international agreements to stem it.

In this context, collaboration is good, if you can get it. But this is hard: like “herding squirrels on a trampoline,” especially when certain countries behave as if they have the incentive to cheat. People feel conflicted, as in ‘we hate undermining poor countries, but (whisper it softly) we like the dirty money coming in.” It’s also hard to get large numbers of people onto the streets to support complex collaborative schemes to help foreigners. So the pushback is feeble.

The Finance Curse, however, offers a completely different approach, because it appeals to selfish national self-interest: “this hurts us.” Once we understand this, then the brakes are off, and we can start really cracking down on this stuff.

And this changes everything.

Conclusion

The Finance Curse is a deep, rich and powerful tool, not just for analysing and understanding many of the most pressing complex economic issues of our time, but also for presenting these to a wide public in a simple way, and providing pointers for deep and widespread reform.

We hope this contributes to public understanding. We’ll amend or add to it as time goes on, and store it permanently on our Finance Curse page.

I never thought of Big Finance like a typical resource curse like gold or oil but it makes sense.

My shorthand remark:

“The financial sector does not make profits, they steal profits from others”

For years I have been ridiculed when I reacted like this to the umpteenth success story about bank ABC or financial conglomerate XYZ’s profitability and thus their contributions to the economy. In this article I find my reasoning justified. Thanks for that.

Now on to the next step: getting rid of these parasites.

Wonderful article, and so nice to see so much information consolidated into one source. The Finance Curse Page will be a great place to send the non-believers.

Somehow though, Shaxson omitted the sector probably the second most devastated after healthcare: education, perhaps because the more egregious manifestations have yet to reach the UK shores or to the scale that education, especially at the higher levels, has been captured by the profit mindset in the US. Or maybe it’s because the UK doesn’t have a billion-dollar college sports industry.

Thank you! I thought of that right away, too. U.S. colleges and universities are nothing more than, really, than a gigantic shadow pay-day loan operation (shadow banking is too dignified a term for them), extracting a huge toll from first, students and their families, but ultimately with the bill paid by the society at large.

This article by Nicholas Shaxson is a great contribution — many thanks to Yves for posting it.

Making money and real wealth creation are two different things.

Money comes out of nothing and is just numbers typed in at a keyboard.

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf

Bank loans create money and bank repayments destroy money and this is where 97% of the money supply comes from.

The last thing a nation wants is too much of the damn stuff or you will get hyperinflation; wheel barrows of money won’t buy anything.

Money has no intrinsic value; its value comes from what it can buy.

The real wealth in an economy lies in its goods and services.

Alan Greenspan tells Paul Ryan the Government can create all the money it wants and there is no need to save for pensions.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNCZHAQnfGU

What matters is whether the goods and services are there for them to buy with that money.

Wealth creation is producing new goods and services in the economy, not inflating the value of existing assets like real estate, stocks, etc …

Wonderful approach! Gets at the information hiding aspects nicely. And for decades I summed this up with “kill all the mbas.”

A useful article, but frustrating. It does not follow the “show, don’t tell” rule. It tells us 17 ways that the finance industry causes problems, but does not show us how. (For example, an infographic shows that payments to Trainline pass through many holding companies, but does not explain how that’s a problem. The article does not explain the difference between wealth extraction and wealth creation, how or why finance costs more than it contributes, or at what point finance gets too big.)

In contrast, the linked Tax Justice Network article “The Finance Curse” by the same author does those things brilliantly. Thanks for leading me to that!

One point I’d add from a US perspective — starting, I think, in the early 1980s, many of the smartest people in the country turned away from government, academia, and science, and devoted themselves to developing ways to extract money from companies, government, and individuals. This was seen not only as morally acceptable, but virtuous, thanks to Milton Friedman and the like. By now, they have developed techniques far more sophisticated than the minds of their prey can handle. A similar progression contributes to the obesity epidemic, a food providers get better at persuading us to eat more.

I’d look at that Trainline infographic as a good start and would like to see similar paths laid out in healthcare. Getting attention to the geography of business is one way to pique curiosity and encourage further research to find out if there is, for example, wealth creation or wealth destruction, or some of both, going on.

Saying your country is “Open for business” confers street cred with the global investor class. I’ve been observing carefully as leaders in my part of the world fall over themselves to give investors assurances to this effect, from Emmerson Mnangagwa in Zimbabwe to our own Cyril Ramaphosa here in SA. With equity, bond and currency markets set up as de facto seisnometers giving near real time readings of investor sentiment, a perfect carrot and stick arrangement is set up to whip any dissenting rhetoric, which is quickly punished by downward market movements and negative press coverage, back into line. Unfettered access for investors and de facto policy and regulatory capture by and in service of said investors, iow your country being “open for business”, is rewarded with markets rallying upwards. This sets up a dynamic where only the most courageous politicians would dare to colour outside the established narrative lines.

Allied with markets and a captured media acting as enforcement arms of the investor class, the jobs vs free rein to the capitalists dichotomy is ruthlessly exploited to cow any opponents of the free market agenda into submission. This is the dilemma facing many developing nations, they’re advised to “compete” by opening up their markets to FDI to create jobs, but for investors the ranks of the precariously employed are seen as leverage in maintaining assymetry in power relations with the state. Given these differences in context, and what appears to my mind to be a better position (in comparison to what developing economies had/have in their attempts to cure the ills of the resource curse) from which to beat back the advances of financialization for developed economies, it remains to be seen whether the finance curse will be every bit as destructive to developed nations as the resource curse has been on many developing nations, but it’s an analogy that sheds light on the pernicious effects of one sector effectively having the entire economy in a choke hold.

Not much to argue with here, except that it’s neglecting the greatest and most enduring danger of a bloated financial sector which is that the bloat facilitates the total corruption of the government and therefore any possible recourse against the financial industry’s predations.

The brilliance of the whole scheme is how government and private corruption work hand-in-hand the whole way.

Money equals speech: Buckley v. Valeo, decided Jan. 30, 1976. What a way to start our country’s bicentennial year!

https://www.oyez.org/cases/1975/75-436

That was also true during the Gilded Age. Then, it was the Standard Oil Trust, and Gould’s railroads, and JPMorgan’s Northern Securities Company.

(They were called Robber Barons for a reason.)

It seems the only way of freeing oneself from financial bondage is just outright rejection. Use as little insurance, healthcare, and housing as possible. How else, baring revolution, to restore the “core” function of finance, which is to make a better life for the multitudes possible. Once the beneficial threshold has passed over into exploitation, there is no peaceful way back. The government must enforce regulations benefiting the collective good, or individuals are forced into servitude and poverty.

What to do? People need to fearlessly face the uncertainties in life. Fearlessly look at the true costs of our current system and lifestyles and choose to forgo individual security. The FIRE sector exists and continues to thrive because it sells the dream of individual prosperity at the expense of collective good. It sells the myth that if the individual is successful, society as a whole, will by default, also be successful and thrive. This is an illusion.

The collective good is a choice born out of individual sacrifice. The cynical and corrupt among us uses this fact as a lever to advance their own interests. Individual sacrifice is redirected from the common good to individual gain. In a word, parasites.

Collectivist or Individualist is the dividing line. This dividing line is best illustrated by the US tragedy of families going bankrupt due to medical expenses. The choice must be made between the hope of individual life or family(group) security and wellbeing. Out of desperation and love, most families choose bankruptcy. How much of this dynamic is free choice or just social conditioning and pressure? People forgoing treatment are most often ridiculed. Instead of focusing on the social tragedy right before our eyes, the dynamic is once again transformed into a selfish individual act.

To make any change possible, one must focus on the collective good above all else- the rest is just kicking the can down the road- until you can’t.

When families have to choose between bankruptcy and losing a loved one, then you know things have tipped over into complete anarchy. It used to be that human life had prime value and all other considerations were subordinate to that, but moral values have inverted to put profit above everything else, and human life is expendable and exists, in so far as the multitudes are concerned, only to swell the bottom lines of the various predators constantly circling us.

I wish people could find it within themselves to fearlessly face the uncertainties of life and harness that courage for the betterment of the collective as you rightly point out, but I fear for the majority the indoctrination of the neoliberal “every man for himself” is so complete that it renders that all but impossible. Most people have been desensitized to the injustices that are a common feature of modern life, and escapism abounds with all manner of distractions from drugs to reality tv shows (and everything else in between) numbing the pain of being subjected to a life of indentured servitude. As you say, there’s no peaceful way back to a more sustainable, equitable model of organizing ourselves as a species. Our apex predators will fight tooth and nail to dismantle any broadbased, grassroots collectivist movements that threaten to wrestle power and wealth from where they’re currently concentrated and many people, pacified by the ad nauseam bombardment with subliminal messaging pointing to the futility of resistance, do not have the stomach for the fight.

Our only hope is a critical mass of disaffected “radicals” who’ve inoculated themselves from being pacified by the propaganda. Akin to the “innovators” in the technology adoption lifecycle, they’re the ones who are going to set the stage for the fightback against parasitic elements in our societies to “cross the chasm” and go mainstream (aided by the greed of the parasites squeezing the multitudes so hard they’re woken up from their propaganda induced slumber). In this regard, the mathematics behind achieving critical mass, which is achieved somewhere between 2,5% and 3% of a whole system altering course, offers hope.

We are having so much trouble getting our concepts straight. Health is a human right, not a “cost”. We are currently trying to externalize the cost of human health services. That’s just like our lazy attitude about the costs of maintaining a healthy environment. Competitiveness is just another c-word. So is externalization. If we thought in terms of a cycle of energy, a cycle of human energy, we would have a much different economy. The economy breaks down when there is an interruption or imbalance in its energy cycle. When we see an opportunity to make a financial profit, but in order to do so we have to waste the environment or exhaust labor, we take it because that’s being “competitive”. It’s such nonsense. That is one reason why being over financed (“over banked” as Wolfgang Schaeuble puts it) exponentiates the destruction of the economy. Finance has become the destroying angel.

A good book illustrating “financialization” is Glass House by Brian Alexander. It describes how practices today associated with private equity etc. have cannibalized the company Anchor Hocking (who makes glassware) and how that process has affected its headquarters town in the Mid-West. It was eye opening for me. I work in finance (with a small f), but have always worked directly for manufacturing companies.

My basic rule is to avoid complexity and buy specific simple single-purpose products.

1. Term life insurance for protecting my family’s future income needs. As our savings build, that need declines.

2. Simple car and home insurance with umbrella policy.

3. Simple, well diversified low-expense mutual funds for retirement accounts. I generally avoid ETFs because my spouse or children would have to learn how to sell them without getting raped by HFT.

4. Simple low fee credit cards

My primary message to my wife and kids is that the finance sector wins when they can convince everyone that it is complex and not easily understood. They then become the equivalent of RC priests chanting in Latin so that they have to be the go-between on everything and they charge a hefty fee for that.

We live in a golden age of personal finance with great inexpensive products that were unimaginable 30 years ago. However, you have to sift through the smoke screen and son et lumiere show to find them. Most people get trapped along the way in some bad products that severely hamper their ability to be financially successful.

Great post. Great charts. Thanks very much.

Great piece. Fantastic analytical framework for examining the impact of finance on the greater economy and society at large. Nice to see someone attempting to encapsulate and categorize all of the specious arguments in favor of financialization, then methodically shred them in a very empirical and succinct fashion.

Another way to look at our current finance system is as an out-moded relic of the Gold Standard when fiat was too expensive/scarce/difficult to create for everyone to use directly but largely only depository institutions, aka “the banks.”

Chart in point one is misleading, as most the finance and insurance lending is ‘plumbing’. The point would be better made by looking at how much lending goes to real estate (specifically mortgages) vs credit to SMEs, ideally showing 1st home mortgages vs second or BTL mortgages.

Credit card interest rates are only going to go up in the future, better to steer clear of accumulating bank card debt!

Another finance curse!

Though an informative article and invaluable article