Yves here. Even if I knew Birmingham better, it would not serve as a point of reference for this study. Birmingham was incorporated in 1871 and its wealthy was based on industry, not agriculture. I wonder what Harry Shearer would say about New Orleans. The one person at Goldman in my day from an old New Orleans family (blockade runners from Civil War) clearly had also inherited money.

By Philipp Ager, Associate Professor of Economics, University of Southern Denmark,

Leah Boustan, Professor of Economics at Princeton and Katherine Eriksson, Assistant Professor of Economics, UC-Davis. Cross posted from VoxEU

One striking feature of many underdeveloped societies is that economic power is concentrated in the hands of very small powerful elites. This column explores why some elites how remarkable persistence, even after major economic disruptions, using the American Civil War’s effect on the Southern states. Using census data, it shows that when the abolition of slavery threatened their economic status, Southern elites invested in their social networks which helped them to recoup their losses fairly quickly.

The antebellum South was a predominantly agrarian and extremely unequal society. The unequal distribution of wealth was particularly notable in the agricultural sector, the main economic engine of the South at that time. One peculiar institution of the Southern economy that contributed to the amassing of wealth in the hands of a very few wealthy planters was slavery. Slave labour and fertile soil were the essential inputs for the cultivation of cash crops (cotton, tobacco, rice, and sugar) on large plantations, while small freeholders cultivated small tracts in the hinterlands. Slaves were also financial assets and served as collateral to finance the new businesses of their owners.

Owning slaves in the South reflected economic status and power and was the exception rather than the rule. Only 20% of white Southern households owned any slaves and as little as 0.5% of households owned 50 slaves or more. Although slaveholding contributed to almost 50% of the aggregate Southern wealth, slave wealth was concentrated at the top end of the southern wealth distribution. The great disparity of wealth reflects the economic power of the richest farmers (planters) in the South before the Civil War. In 1860, a household at the 90th percentile of the southern wealth distribution owned 14 times more than a household at the median; for comparison, the 90:50 ratio was roughly 7:1 in the US between 1950–2000 and is at 12:1 today (Kuhn et al. 2017).

The Civil War constituted a major rupture for the Southern economy. With the formal abolition of slavery in 1865, wealth from slave-holding evaporated. Land values also declined substantially after the Confederacy’s defeat, reflecting lower levels of agricultural productivity after the war. Overall, these war-related events led to one of the largest compressions of wealth inequality in human history. Compared to 1860, a white household head at the median of the Southern wealth distribution held 38% less wealth in 1870. The wealth of the top 10% wealth-holders fell even by 75% such that the 90:50 ratio dropped from 14:1 in 1860 to 10:1 by 1870.

The magnitude of this large wealth shock with the associated compression of wealth inequality naturally brings up the question whether the planter class, including their offspring, disappeared from the upper rung of the southern society. In his 1951 book, Origins of the New South, C. Vann Woodward argued that the Civil War led to a decay of the southern aristocracy. Since then, this has been the conventional view of postbellum southern history. In our new paper, we challenge this view by showing that despite significant wealth losses, the families of wealthy southern slaveholders regained their economic status within a generation (Ager et al. 2019).

Data and Method

Our new assessment of this long-standing question in American economic history is based on newly digitised complete count records of the US Census. These records contain information that allow us, to follow household heads and their sons over time with standard linking techniques. We construct linked samples of more than 200,000 household heads from 1860 to 1870 and 350,000 sons from 1860 to 1880 and 1900. The main analysis exploits information on household wealth in 1860 and 1870 and proxies for the wealth of sons in 1880 and 1900 (the Census collected no systematic information on individual wealth after 1870).

We evaluate the transmission of the Civil War wealth shock by using two different approaches. The first approach compares white Southern households whose surnames, on average, were associated with high/low slaveholdings in the same percentile of the national wealth distribution in 1860. For the second approach, we link as many households as possible to the slave schedule of the 1860 Census and compare those known slaveholders that are in the same percentile of the 1860 wealth distribution but invested more/less of their wealth in slaves. To account for localised differences in agriculture, we control in both cases for area fixed effects (county or state).

Results

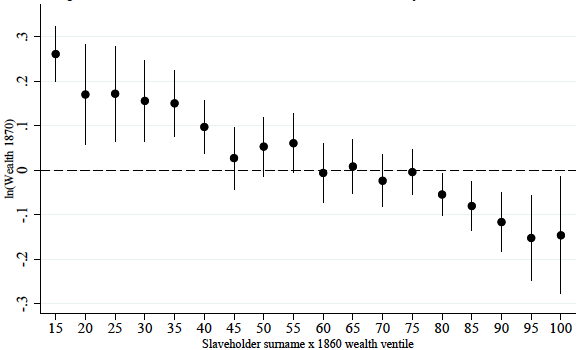

Our main finding for household heads in 1870 is illustrated in Figure 1 (note the main effects of 1860 wealth percentiles are not reported). Households with likely slaveholder surnames held identical wealth as non-slaveholders in 1870 if they were located between the 40th and 70th percentile of the 1860 wealth distribution. This pattern changes substantially for likely slaveholders that were at the top of the 1860 wealth distribution. For example, at the 90th percentile, households that likely owned slaves in 1860 retained just about 15% less wealth by 1870 than similarly wealthy counterparts.

Figure 1 The effect of slaveholder surname on 1870 household wealth by the 1860 wealth distribution

Source: Ager et al. (2019).

A similar pattern emerges for known slaveholders – those who had relatively more slaves in their portfolio in 1860 experienced substantially higher wealth losses by 1870 than their similarly wealthy counterparts who invested less of their wealth in slaves.

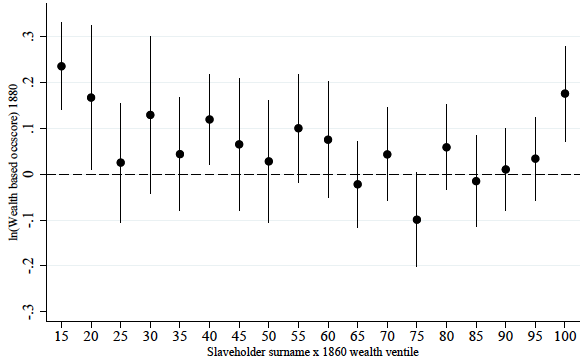

Figure 2 (note that the main effects of 1860 wealth percentile are not reported) shows that despite the large wealth losses that slaveholder households experienced, their sons did not perform any differently than the sons of non-slaveholder households in 1880. If anything, the sons of the wealthiest likely slaveholder families even outperform their counterparts.

Figure 2 The effect of slaveholder surname on 1880 household wealth by the 1860 wealth distribution

Source: Ager et al. (2019).

We can even ask what would have happened to the Southern elite if, besides slave wealth, they also lost their land. While land distribution did not occur at a large scale after the Civil War, we can assess such a scenario by looking at two specific regions where landholders were either temporarily expropriated (the areas affected by Special Field Order No.15 – the confiscation of a strip of land along the seaboard of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida) or their land and capital being destroyed (the areas affected by Sherman’s March to the Sea – a military campaign that followed a policy of ‘scorched earth’ in parts of Georgia and the Carolinas). Despite the fact that, in both cases, wealthy household heads in these areas experienced substantial wealth losses relative to similarly-wealthy households in adjacent counties (up to 40%), their sons completely caught up with sons of comparable wealthy families in those neighbouring counties.

What can explain the recovery of the Southern aristocracy despite such substantial wealth losses? We provide evidence that existing social networks were the most likely explanation for the resilience of the Southern elite. These networks facilitated employment opportunities and access to credit. We discover that slaveholder sons married spouses from households that were wealthy before the Civil War, which provided them access to the networks of their affluent fathers-in law. Sons also shifted into white-collar work, a process which the social history literature attributes to family connections.

Overall, our results indicate that the wealth shock associated with the Civil War and the abolition of slavery was not transmitted to the next generation. While these findings are based on comparing households within the South, one well known fact is that the North outperformed the Southern economy for more than a century after the Civil War. When comparing wealthy Southern households with Northerners that were at the same percentile of the national wealth distribution in 1860, we find that Southern households experienced substantial wealth losses. While similarly wealthy Northerners held at least 50% more wealth in 1870, a substantial part of this wealth loss was also transmitted to future generations and disadvantaged the sons of the Southern elite relative to their Northern counterparts (this gap started to disappear by 1900).

The persistence of the total Southern wealth loss indicates that it was not the transfer of slave wealth from slaveholders to former slaves per se that mattered but differential productivity shocks in agriculture and manufacturing that substantiated the North-South gap after the Civil War. Our findings on elite resilience after the war is consistent with Acemoglu and Johnson’s (2008) theory on elite persistence – the elite used their de facto power (in our case their social connections) to overcome the loss in de jure power (in our case the abolition of slavery and black enfranchisement). The rise of sharecropping arrangements and the implementation of anti-enticement laws to restrict the mobility of the agricultural labour force can be regarded as responses of the planter class to Reconstruction efforts after the war. In that way, they managed to preserve the ‘old’ Southern economic structure and retain their relative economic position within the South.

Conclusion

Our findings of elite persistence questions the traditional view of a decaying southern elite after the Civil War. When the abolition of slavery in 1865 and other reconstruction policies threatened their economic status, they invested in their social networks which helped them to recoup their losses fairly quickly. The recovery of the southern elite also indicates that while occupational mobility in the US was rather exceptional at that time this was definitely not the case in the postbellum South.

Editors’ note: This column first appeared on the Pro-Market blog. Reproduced with permission.

See original post for references

I think most sociologists would argue that social connections are incredibly important in maintaining elites, even when they’ve been wiped out economically. You can see the same in Germany and Japan after WWII, where even after devastation elite families who lost everything often recovered quickest (although it was more often the business elites rather than the landowning ones who did best as the latter were generally treated more harshly by the occupation authorities). A few years ago I read a study on Asian immigration to the US in the 20th Century – many of the Vietnamese and Chinese refugees came from their countries elites, but were entirely impoverished on arriving in the US, but became extremely successful within a generation (this success was not matched by those who came from humbler backgrounds). While a strong educational background no doubt helped, its hard not to attribute much of the success to being able to tap into networks of well-connected people around the world.

As to the marriage thing – a feature of many wealthy agriculture families in southern France and northern Spain is Irish surnames (think Hennessy Brandy, or Lynch-Bages wines). This came about from Irish catholic landowning families in the 18th Century, subject to strong discrimination and confiscations from the Anglo-Irish aristocracies sending sons to Europe to marry into wealthy catholic families. These young men wouldn’t have had much except recommendations through the Church and the prospect of merchant connections to import wine to Britain via Ireland. But it served both Irish catholic elites (both landowning and merchants) and the Continental ones to make those connections for mutual advantage, so those marriages happened.

One of these was Leopoldo O’Donnell, born in Biarritz in 1809 descendant of Calvagh O’Donnell, chieftain in Tyrcornnell. He became an influential military and politician (moderate-progressive) in Spain during 19th century.

Typo: Tyrconnell, now Donegal

Indeed, the O’Donnells were proud warrior aristocrats of the north, like many lost everything to the Plantations.

Just to elaborate, the point I was somewhat clumsily trying to make is that marriage across aristocrats/elites is one way they perpetuate themselves when their original base of power has been removed. The old Irish aristocracy used their catholic connections to find an alternative economic base in Europe and so established a foothold.

It does show why confidence tricksters throughout history almost invariably pretend to be foreign aristocrats as part of their identity.

Did not some go into the military as well? I seem to recall that the French Army had Irish Regiments.

One way back for the exiled aristocrats I think was to become bodyguards for foreign kings. Presumably they had the fighting skills, a modicum of courtly behaviour and were perhaps less of a danger to the monarch than their own subjects.

I recall the French kings had Swiss bodyguards?

Thats very true – many young Irishmen who lost their inheritances found a role fighting, especially in France. As you suggest, many Kings and Emperors preferred foreign fighters as they were less of a threat internally, and the landed aristocracy always knew the value of teaching younger sons how to use a horse and sword.

And Irish women were quite handy at their own skills, including (allegedly) provoking a war or two.

a little late to the game, but…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Garde_%C3%89cossaise

scottish garde

What you said must have applied to Scotland as well. One of Napoleon’s Marshalls was named Etienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre Macdonald and who was the son of a Scottish Jacobite that fled Scotland and went into exile in France after a failed rebellion. After the Napoleonic wars were over, this character went to visit his ancestral home in Scotland and though unable to speak English, could still speak Gaelic to talk to the locals with.

I’d add that the social structures of both Germany and Japan were highly sophisticated and survived the war more or less intact. Indeed it could be argued that in Germany the defeat of the Nazis and the (albeit imperfect) de-nazification process actually brought traditional elites back into power. The obvious contrast is with Russia where the elites were wiped out or driven into exile. Social capital is enormously important for economic regeneration and these two countries are examples of where it was preserved. By contrast the former Yugoslavia had a society organized around the Communist Party, and once that fell apart there was nothing holding the various republics together. That’s essentially why the successor republics have been mostly economic failures ever since.

Re: Yugoslavia “That’s essentially why the successor republics have been mostly economic failures ever since.”

Not entirely supported by the evidence. Slovenia has reached Spain-level nominal GDP and Israel-level PPP GDP; Croatia is ahead of Mexico (E.g.) in nominal GDP and is about level with Chile in PPP GDP. Yes the successor republics are in the second tier of economies but hardly economic failures. And IMHO Serbia would be better off but for the Empire’s continuing persecution of that brave nation.

Agree about Serbia. Some of the others have benefited enormously from proximity to European markets, tourism and foreign investment. But that disguises the underlying weakness of most of the FRY states. Bosnia is the classic case of an economy which has never really recovered because of the absence of social capital to support investment. It used to be argued (it may be less true now) that the only really effective economic sector in the FRY was organized crime, precisely because it was structured around groups with high social capital.

This is of course one reason why both the Nazi’s and NKVD were so ruthless about eliminating entire classes of people in Eastern Europe when they got a chance, as at Katyn.

Its certainly been argued (by the War Nerd as one example), that the US would be a much better place had the Union shown the same ruthlessness towards the Confederacy.

This is a good observation. Related to the renascence of Confederate era aristocratic families, like those in post WW2 Germany and Japan, they all had deep business conncections abroad. This particularly helped Germanyand Italy, though Japan had been briefly the subject of friendly fascination in the UK and US due to their participation in WW1 on the allied side. Patterns of trade and business contact had a huge amount to do with how they bounced back. You read again and again in Civil War accounts how a northern businessman has spent years in the south selling cotton gins or whatever and developing fclose riendly ties with the local gentry who formed their customer base. Similarly, southerners sent their sons to places like Yale and Harvard. Both regions shared the military officer corps- North and South were joined at the hip at West Point which is in…New York.

What this article makes me most curious about is: how many prominent families in Italy today have direct kinship ties to Roman era senatorial class families? Everybody in northern Italy looks German, so maybe the bounceback factor here is more a product of the global/modern era (post 1500)

Statistical proof:

[In the South] “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Wm. Faulkner

Disclaimer: I’m a Southern exile of Faulkner’s second type.

Strong social networks provide access to employment opportunities and to credit. Country clubs, beach clubs, tennis clubs, board positions in museums and symphony orchestras, the University Club, Bilderberg, Davos …. if you belong and follow the rules (unwritten) you, and your offspring, have access to jobs, money and power.

But when the working class, immigrants and the even more disempowered groups, who can’t get access to the most rudimentary ‘legal’ way of obtaining money, attempt to form strong social networks …. unions, so-called ‘gangs,’ the Mafia ….. they are hounded to dissolution, harassed by cops, incarcerated and, in many cases, murdered.

Really, the only way ‘legal’ way for the underclass to form strong social networks is to ‘get religion’ and join a church.

…and then the ‘ministers’ exploit them through tithing and dreams of a heavenly afterlife.

I do agree that churches are the go-to organizers of the proletariat.

And unions? Not so much anymore.

Not just the church, sports networks can be very powerful too – the problem though being that working class sporting networks don’t give the clout of upmarket ones. But certainly I know good rugby players who have used that connection to immediately get good jobs when moving between UK/Ireland/NZ/Oz.

“the only way ‘legal’ way for the underclass to form strong social networks is to ‘get religion’ and join a church”

Wealth by religion: U.S.

http://money.com/money/4526671/religion-wealth-income-jewish-hindu-atheist-episcopalian/

Billionaires profiles: World

http://www.slate.com/articles/business/billion_to_one/2013/11/the_world_s_top_50_billionaires_a_demographic_breakdown.html

Re:

Despite the use of the word wealth, the study is about income.

The article you cite and the Pew study on which it’s based both indicate that a more likely and documented correlation with education rather than religion.

Even as a perspective on income/religion the extreme granularity applied to US Christian or Protestant categories would have an impact on the rankings. Pew has a lengthy explanation of how they assign these categories.

Classical divide and conquer, it’s like the ABC of oppression, limit ability to interact and organize. And if these fail, one can ‘decapitate’ organizations in various ways.

One comment blamed Soviet Union for the destruction of elites, but history is full of examples where elites control masses by destroying their leaders. These tactics aren’t specifically left-wing tactics, it’s just more that the elites are far more adept crying out apparent injustices like what Soviets did, but the elites themselves employ these tactics far more.

Note that Elites are rightfully scared nowadays, the masses have much more effective tools to disseminate information and organize today thanks to social media. That’s why it’s predictable that Elites will continue moving to control social medias increasingly in the future, like China is doing right now.

One takeaway from the above could be that extreme inequality leads to extreme outcomes–i.e. a Civil War that killed half a million Americans. In my state the poor and non slave holders had virtually no power at all before the war and the upper SC strata led the South out of the Union and to great disaster. In our current era it has become obvious that the elites will do anything to defend their privileges including trillion dollar bailouts and continuous overseas wars to keep the rest of the planet in line.

The civil war devastated the south in that most men went to war and few stayed home. The Republic of Suffering gives a good picture of what was happening at home. Yes, the largest slave holders were hurt but it must be remembered that the slaves still had to work and continued to be exploited with the new laws that cropped up to control blacks. The Bloody Shirt shows that a new form of slavery evolved within seven years.

So interesting. Thank you for this sorta low key research. Some thing jumped out right away: that the slaveholders who were over invested in slaves (i.e. maximizing their efficiency) took the biggest losses when slavery was abolished. Those former planters who were more moderate took smaller losses. But even so they all had recovered by the time the next generation entered the economy. I think that becomes less and less possible as the population expands and sustainability is diminished. The Millennials are having a hard time finding a place in this economy. It is not like it was a century ago. After the Civil War the North was Rich and the South suddenly poor, comparatively. It took the South about 50 years to catch up to even. This was how long it took to transition from agricultural to industrial. The South spent a lot of energy industrializing their own textile industry. Cotton mills. Mill towns. They competed with the North and achieved new wealth. There have been several iterations of the “New South”. There is even one going on right now because their furniture and textile industries were decimated by underlying economic unsustainabilities – just like their former plantations. After 1865 the southerners, white and black, went where the work was. They were mobile because they only had one option. Eke out a starvation existence or go find a job. So even though wealth was restored in the South, it seems future wealth was restricted in a long process kinda going from excessive plantation/slavery exploitation, to maximum industrial competition, to socialism, to fantasy (the American Dream – think Elvlis), to the new realities of environmentalism. And now, looking back with this research it is almost depressing to see we really haven’t yet come to a clean break with former beliefs in wealth itself. It’s nice to know that everyone is now wondering what the hell it is. I like that part. Because it implies we will all cooperate, not just the socially connected wealthy.

I am familiar with the history of both the US South and Mexico.

Whatever the underlying cause of the inequality, the mechanism for its perpetuation is violence. In the post bellum South, the terrorism of the night rider groups as well as the police. In Mexico, the police and sometimes the Army.

It really is as though the Conquest never ended in Mexico. Ever since Cortes, state violence is used to put down popular attempts to stop the looting. This has frequently included attacks on union organizers.

Maybe take a page from China: the best way to stop the looting is to stop the manipulation of commodity prices. Or one of the best ways. Must refute that down to the capillaries.

You mean like the price of petroleum?

And students

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-45705009

And much more recently:

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/20/mexico-43-killed-students-

And the looting gets institutionalized even more:

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2019-05-31/largest-foreign-bribery-case-history-claims-new-scalp-former-pemex-ceo

Unfortunately values travel. Quoting the judge from Santa Cruz about a week ago on N.C.:

May 25th, running out of time to find it..

“What constantly struck me was the neoliberal article of faith that American laws and cultural norms are some sort of “natural laws of free markets” and that immigrants were expected to automatically adhere to traffic laws and sexual mores (for example) that were completely alien to them.”

We have much more recent experiences that help us examine this phenomenon, namely the Russian revolution, the New Deal, and the Cuban revolution and subsequent refugee culture of Miami to name a few.

Think about the loss of wealth and status associated with all these historic events.

Ayn Rand’s bitter reaction to her family’s loss of wealth and position during the Russian revolution, resulting in her invention of objectivism, a sort of framework for imagining a utopian capitalism.

There are still families holding a giant grudge against FDR over the confiscation of gold, which in part explains the animus on their part toward the New Deal, which exists today, and has for all these years.

Nobody can deny that the Cuban exile community in Miami includes a significant number of folks who demonstrate the same sort of resilience that the author attributes to networking amongst the formerly wealthy southern planters.

Old money never forgets, and strives to maintain the social network that enables them to rebuild wealth and power in the face of political resistance, economic upheaval and even successful revolutions.

They aren’t happy to be opposed, let alone defeated, and even in defeat, seem to consider themselves only temporarily inconvenienced.

Indeed, in the USA, one of the tactics they have used pretty successfully to oppose socialism is to convince much of the the working class that they too are only “temporarily inconvenienced millionaires”.

These intergenerational memories, yes, going back all the way to the Civil War are in great part, the spice that makes our politics taste so reactionary.

Lotta revanchism goin’ on. (Could be a song in there, somewhere.)

“I wonder what Harry Shearer would”

I’m dying to find out how that sentence ends. I became a devotee of this blog after hearing Yves interviewed on Harry Shearer’s Le Show.

Oh, so kind!

I thought I had deleted that part but I finished the thought instead.

The phenomenon of “elite persistence” is something we Westerners appreciate. Its what Bilderberg and the other richmen’s clubs are involved in promoting. Once you have become inured to calling the shots you are almost incapable of being on the receiving end. Employers make poor employees.

What this really omits–oddly–is the history that followed. Because after Reconstruction the ruling class, through incredible violence, reclaimed political and police power. As the groundbreaking Pulitzer Prize-winning Slavery By Another Name shows, slavery was perpetuated through the convict lease system of terror, in which labor for the derelict plantations and emerging new enterprises (coal, steel) was obtained. Some plantation wealth was reinforced, a new elite emerged (in the main from it) and a thin stratum of poor whites gained a measure of wealth, mostly by serving as the police power for a renewed plantation aristocracy. The role of southern prisons also cannot be overlooked–it kept wages low and the poor white and black populations in submission. The Department of Agriculture ran the prison systems in many southern states up through the 1960s. The critical piece here is that the subjection of the black population didn’t end. You cannot understand the period, or the continued poverty of both black and white America, without reading the emerging new historiography, books like the above or The Half Ain’t Been Told. Wealthy social networks are of course a piece of the puzzle, but secondary to the brutal coercive power of governments (often working with northern capital, btw), in my view.

Another good book is “Slavery’s Capitalism; A New History of American Economic Development”.

Slavery By Another Name, Douglas Blackmon

The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, Edward Baptist

should have looked these up before posting

Land redistribution, as everywhere after colonialism–backed by programs of serious aid to the formerly enslaved and poor whites–would have been the only real way to powerfully reconfigure wealth and deep-seated inequality

Thank you for your comments. I’m only part way through The Half That’s Never Been Told, and still learning to understand how Northern and global financial and commercial interests aligned with those of the plantation owner class, before and after the Civil War. It’s disconcerting to read this analysis with stolen people, and the stolen fruits of their labor neutrally referred to as wealth lost or retained by the enslavers. That may be ok for an economic model (I claim no expertise) but I agree we need to understand the workings then (and now) of coerced labor and institutional violence in enabling the accumulation and retention of wealth.

I remember the awareness in my childhood that incomes in the South Carolina I grew up in were lower than in the North. I heard former Senator Fritz Hollings say that South Carolina had no industry except for textiles until after WW2, when Celanese, a British corporation, made a huge investment along the Catawba River. He said the British said, ‘But you don’t know how to do anything!’ before they finally were persuaded to invest.

Some of the comments on this piece suggest that agricultural societies are necessarily poor, and industrial societies are necessarily rich. I don’t think that’s so. Argentina was almost completely agricultural a hundred and twenty years ago, and they were one of the ten wealthiest countries in the world (it was the populism that did them in). The South might have developed along the Argentine model, but without the populism. Industrial economies won’t find themselves to be wealthy if worldwide industrial capacity continues to grow faster than demand, as it has done for many years.

I suspect the Southern planters recovered to the extent they did in part because they were among the most educated members of society. The book ‘Ebony and Ivy’ recounts how graduates of Ivy League schools came south to teach the children of the planters, who were often educated at home. De Tocqueville describes southerners in ‘Democracy in America’ as being ‘more intellectual’ than their northern counterparts. It’s but a short step from the plantation to becoming a professional, whether doctor, lawyer, or teacher.

Eugene Genovese, the late, great, historian of slavery, thought the planters were interested in staying on top the social pyramid, but that money was secondary to that end. In his language, and he was a Marxist until after he was fifty, the planters ‘challenged bourgeois values’.

I believe, though it would be hard to test this thesis, that the average white southerner involved in the Democratic Party is likely to be descended from the plantation class, for reasons that a close reading of Genovese’s ‘The Political Economy of Slavery’ would make clear.

Or it could just be IQ which is the best indicator of success. The slave-owners had to have better IQ’s to make the plantations successful in the first place. They were able to use their IQ’s to start all over to be a success again.

I think you’d have to isolate that to…”among slaveholders, those with higher iq succeeded more frequently” to prove your thesis and, of course, provide some kind of citation

I wonder how much IQ does one need to “successfully” grow sugar and cotton using slave labor.