By William H. Dow, Professor of Health Economics, University of California, Berkeley; Anna Godøy, Research Economist, University of California, Berkeley; Chris Lowenstein, PhD student in Health Economics, University of California, Berkeley; and Michael Reich,Professor of Economics, University of California, Berkeley. Originally published at VoxEU

Policymakers and researchers have sought to understand the causes of and effective policy responses to recent increases in mortality due to alcohol, drugs, and suicide in the US. This column examines the role of the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit – the two most important policy levers for raising incomes for low-wage workers – as tools to combat these trends. It finds that both policies significantly reduce non-drug suicides among adults without a college degree, and that the effect is stronger among women. The findings point to the role of economic policies as important determinants of health.

Since 2014, overall life expectancy in the US has fallen for three years in a row, reversing a century-long trend of steadily declining mortality rates. This decrease in life expectancy reflects a dramatic increase in deaths from so-called ‘deaths of despair’ – alcohol, drugs, and suicide – among Americans without a college degree (Case and Deaton 2015, 2017). Between 1999 and 2017, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths increased by 256%, while suicides grew by 33% (Hedegaard et al. 2017, 2018).

In their pioneering work first highlighting these trends, Case and Deaton point to declining economic opportunity among working class non-Hispanic whites – combined with an increase in chronic pain, social distress, and the deterioration of institutions such as marriage and childbearing – as primary drivers of these trends. Case (2019) further notes that inflows of cheap heroin and fentanyl interacted with ongoing poor economic conditions among less-educated workers to perpetuate mortality due to these causes. Other scholars have questioned the explanatory focus on distress and despair, especially for drug-related deaths (Roux 2017, Ruhm 2019, Finkelstein et al. 2016). These researchers point instead to place-specific and ‘supply-side’ factors of the drug environment, particularly the role of new, highly addictive and risky drugs. Others have also pointed to the role of the obesity epidemic and the lagged effects of the HIV/AIDS crisis as drivers of these trends (Masters et al. 2018).

We contribute to this discussion by examining how two economic policies that increase after-tax incomes of low-income Americans – the minimum wage and the earned income tax credit (EITC) – causally affect deaths of despair.

Our Study

To estimate the causal effects of minimum wages and the EITC on mortality, we adopt a quasi-experimental approach, leveraging state-level variation in state economic policies over a 16-year period from 1999-2015. Our primary data source consists of geocoded CDC Multiple Causes of Death files linked with state-level demographic, economic, and policy variables from a variety of sources (see Dow et al. 2019 for a full description of data sources and methods).

The restricted-access mortality files we use contain various demographic characteristics including race, ethnicity, age, gender, and education. Education is of particular relevance to our analysis as it serves as a proxy for exposure to the EITC and the minimum wage. We focus specifically on mortality among adults aged 18-64 without a college degree, as this is the population most likely to be affected by minimum wage changes and the EITC. While the term ‘deaths of despair’ typically includes deaths from drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related illness (Case and Deaton 2015), we focus here on drug overdose deaths and non-drug suicides, which are more likely to be responsive to recent policy changes in the short-run.

Our analysis follows the standard difference-in-differences approach to estimate models of cause-specific mortality over time. Our estimates suggest that both policies significantly reduce non-drug suicides among our lower-educated sample (adults without a college degree). Specifically, we highlight three findings. First, a 10% increase in the minimum wage reduces suicide deaths by 3.6%, while a 10% higher maximum EITC reduces suicides by 5.5%. Based on the average annual suicide rate in this population over the study period, this translates to a reduction in over 1,200 suicides annually.

Second, the effect of these policies on reducing suicide is stronger among women. A 10% increase in minimum wages (state EITC credits) leads to a 4.6% (7.4%) reduction in suicide deaths. This is consistent with differences in exposure to these policies, as women are more likely to work minimum wage jobs and to be eligible for the EITC.

Third, we do not find any differential effects of minimum wages on suicide for white non-Hispanic and other racial/ethnic groups, yet there is suggestive evidence that the EITC may have larger effects among people of colour.

Overall, we find that the reduction in suicides is greater among the groups that are more likely to be affected by higher minimum wages and generous EITCs. We find no significant effects of these two policies among adults with a bachelor’s degree or higher – a population less likely to work minimum wage jobs or to be eligible for the EITC. This finding lends support to our hypothesised mechanism that these policies reduce suicides by lifting low-income groups out of poverty. Importantly, neither policy significantly affected drug-related deaths, which have increased in the US with the greater availability of illegal opioids, heroin, and fentanyl. These null effects are consistent with the arguments made by Ruhm (2019), Finkelstein (2016), and others highlighting the supply-side drivers of the dramatic increase in drug overdose fatalities. It is likely that other policies are needed to combat these trends.

Evidence of Causality

Our study provides the first causal evidence of the beneficial effects of these policies on fatalities attributable to non-drug suicide. Underlying our study design is the fundamental assumption that we can obtain causal estimates of policy effects by comparing states that have different minimum wages and EITC rates within the same year. For this approach to be valid, the parallel trends assumption must hold – that is, changes in state minimum wages and EITC rates should be uncorrelated with unobserved drivers of mortality.

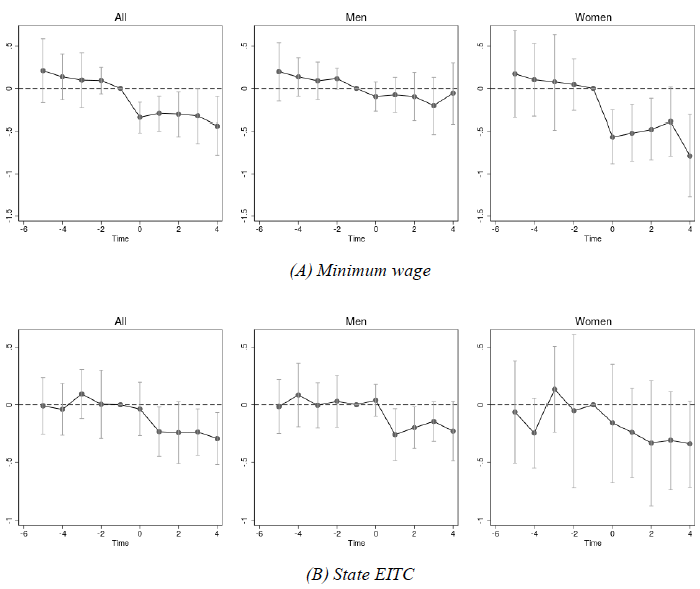

We provide strong evidence of the parallel trends assumption by estimating an event study model that captures the time path of effects around the time of minimum wage or EITC change. The intuition behind these models is that higher minimum wages or EITC rates should not have any effects on mortality in the years leading up to the policy changes, but we should observe a discontinuous shift in the outcome at the time of implementation. This pattern is shown in Figure 1 plotting the estimated effects (and their 95% confidence intervals) for the minimum wage (panel A) and EITC (panel B), each stratified by gender.

Figure 1 Event study models of non-drug suicide

Concluding Remarks

Our finding that minimum wage increases and EITC expansions significantly reduce suicide rates are consistent with recent research identifying economic correlates of suicide – non-employment, lack of health insurance, home foreclosures, and debt crises (Reeves et al. 2012, Chang et al. 2013).

More generally, these findings further an emerging body of literature examining the relationship between economic policies and related health behaviours and outcomes. For example, recent research has found that minimum wage increases lead to reduced self-reported depression among women (Horn et al. 2017), reductions in suicide (Gertner et al. 2019), and do not have harmful effects on teen alcoholism or drunk driving fatalities (Sabia et al. 2019). In general, a majority of the recent papers on the effects of minimum wages on health have identified beneficial effects, though many of these studies use questionable methods that cast doubt on their validity as credible causal analyses (Leigh and Du 2018, Leigh et al. 2019).

Expansions of the EITC have been found to significantly improve the health of mothers and birth outcomes (Evans and Garthwaite 2014, Hoynes et al. 2015, Markowitz et al. 2017), and a recent study by Lenhart (2019) finds that EITC expansions improve self-reported health. Taken together, these findings point to a substantial public health benefit of increasing the minimum wage and expanding the EITC.

The minimum wage and the EITC each raise incomes for low-wage workers. Economists have generally found that minimum wage policies increase income and reduce poverty, while having very little to no negative effects on employment. The new findings in this study suggest that the benefits of minimum wage and EITC policies are broader than previously thought and can help combat the high and increasing levels of deaths of despair.

See original post for references

Dubious choice of variables. Minimum wage affects both genders, but EITC goes mainly to females. Suicides are mainly by males who are in despair because of lost USEFULNESS, not because of lost wages.

And how are wages not part of ones usefulness, especially in a hyper-mega-ultra neoliberal capitalist regime?

Exactly! Even though I have no dependents, a large part of my usefulness is my financial ability to help others, whether that is friends, through charity, animals, supporting political candidates/websites, whatever. With no money most of my usefulness would be GONE. Puff!

And although I’m an amiable and kind person who is important to my siblings and some friends, I still think my usefulness is more than 50% dependent on my financial solvency and ability to earn money.

That’s right: Money! Cash Money! Das Kapital, baby!

One of the many dilemmas we’re facing is the struggle to improve people’s material lives – health, housing, education, et. al. – which involves political struggles over money and investment, precisely so that people can live their lives without money dominating every last cell of their existence…

EITC goes mainly to PARENTS, I don’t think it’s mainly to females, could be wrong.

Lost usefulness is a PART of the misery of unemployment but lost WAGES are also a big part. And when you lose wages you lose your usefulness to others in helping provide, as well. Money matters.

EITC is greater for single parents, single parents are overwhelmingly female. Also, much more likely to meet low income requirements in a single.income household.

Tax nitpicking here, but it’s not true that EITC is greater for single parents. The maximum EITC ($6431 in 2018) is the same for single parents as it is for married parents. However, you’re correct that single parents are more likely to receive EITC – on average, they have lower total earned income & are therefore less likely to hit the EITC phaseout. (The phaseout is higher for married couples but that typically doesn’t make up the difference of having a second wage earner – eg, for single parents the credit begins to drop at about $19,000 of earned income, whereas for married couples it drops at about $24,500).

FYI for divorced or separated parents, EITC benefits are received by the primary custodial parent even if the other parent is still the main breadwinner & claims the child’s CTC (and, formerly, their dependent exemption) – that’s why EITC specifically usually goes to the mother (whereas fathers who pay child support often receive CTC as part of the agreement).

Shades of the “mindfulness” article from a couple of weeks ago. I’m not convinced being better adjusted is the right answer. This essentially asserts that the white non-hispanic demographic can be consoled once they are reintergrated as consumers of (admittedly) limited luxury. Even the despondent poor can become indifferent precariat with some small policy changes. Then, they too could become the byproducts of a lifestyle obession.

That’s obviously easy for me to say from the desk of my comfortable middle class job though.

I don’t see where one gets luxury or lifestyle obsession from this, it’s about lifting people out of poverty.

your last sentence made up for my uneasiness at the rest.

kudos.

these things make a big difference. EITC, especially.

we built this house with that(mostly), and planted all those fruit and nut trees….but even if some single mom “blows it” by getting a cabin by the lake, or most of the other things Ive heard complained about…tv’s…whatever…it’s a good thing.

when that check comes in, it feels like living like folks, for once.

Minwage has a less salutatory effect…it’s rarely raised, and then by too little to make a big splash.

I totally concede that the proposed policy changes are by no means minor to minimum wage workers themselves. Additionally, I’d concede that the proposed change from the article is realistic and actionable. As such, it’s far superior to the Left’s default policy of bemoaning the gap between real and ideal states. And far be it from me to knock low wage earners getting “handouts” when the nature of what people get paid “good money” for is already so ridiculous.

Call me crass, but my point is that most policies feel like half measures at best in light of the havoc climate change will wreak. Saving suicidal workers so they can participate more fully in the post-capital death dance with us serves primarily to assuage our guilt and validate capitalist realism, IMO. Mass extinctions and the failure of human civilization is the only alternate viewpoint that I can envisage other than capitalism.

Swabbing the arm before we administer the lethal injection is a nice gesture though.

“Saving suicidal workers so they can participate more fully in the post-capital death dance with us serves primarily to assuage our guilt and validate capitalist realism”

No it doesn’t, it’s giving people what they need in the now and saving them from committing suicide because of the cruelty of the economic system. I believe people have a *right* to kill themselves, but it’s not ok for them to be driven into it by the cruelty of the economic system.

Even if climate change kills everyone in say in 5 or 10 years, even then that doesn’t make it any better for economic despair to cause people to off themselves now. If it does then you and I and everyone else ought to also off ourselves now (and maybe kill one’s kids for mercy). But we don’t, do we? So why should economic unfortunates be forced to by the inability to make it economically?

In some sense yes, no other issue matters but ecological collapse. Really literally nothing else matters as much. Some days I can’t think of much else either. And if everything is as hopeless as all that, I don’t see why so much hoopla is made over elections etc.. But still, I really don’t see how that relates to this subject at all. These people aren’t killing themselves because of the death of the biosphere, not that that might not figure in (as in: “I have no future, and neither does the world”), but because they can’t make it economically.

It relates because we’re talking about performing maintenance on the same machine that’s killing us. I’m saying it’s a sad state of affairs, a band aid on a gunshot wound. The pervasiveness of capitalism is such that the only comfort we can offer the hopeless is a bit more cash. More sad than that, that’s all it takes! In reading and believing this, we stoop a bit more because the true impoverishment of peoples is that they have become completely powerless without money.

I don’t mean to reduce these very real people to the order of symptoms, but in the sense that we are all like a large organism, and given their growing radical rejection of western life, the real source of the problem is the belief that the economic itself should be saved. It is the problem and we’re, ultimately, discussing treating symptoms.

Killing our kids as a mercy is just ridiculous. It’s not like everyone drops dead the moment you can’t login to your bank account. But it does speak to my point that many of us accept that the economic dream is dead but we, with passionless zombie-like drive, refuse to alter course.

So long as we don’t believe a future is possible what’s the point of doing anything other than playing out our present selfish hedonistic nihilism? For most of us, as I said before, it’s to assuage our guilt. I’d add however, it’s also to relieve our feelings of total powerlessness because economic participation is the only power we have left. My diagnosis: Kill the dream.

Please don’t drag down nihilism by using it synonymously with hedonism.

Hedonism and sensualism are logical responses to nihilism. The many equivocally “spiritual” Christian-by-default types in the modern West understand this instinctively if not explicitly.

I’m not sure why anyone would want to champion nihilism though.

Thanks, JRS. I think hopelessness is a luxury that prevents much good being done and I agree with your positive approach. Every difference MATTERS.

The seemingly unanticipated effects of the crack down on opiod prescriptions is having far reaching consequences. The deaths of despair will continue for decades. Not only are chronic pain patients being stigmatized, force tapered and abandoned by physicians, they are turning to street drugs and committing suicide at record rates, I’ve seen countless stories and actually know persons affected in ways that were previously unfathomable. Raising minimum wage and tax credits are a start but communities and connections eroded by class & income & education differences, “smart” phone isolation from the real world, and the likelihood of any meaningful policy lever effects in this political age will not be solved by more trickle down parlor tricks.

I am on Disability and went to the homeless shelter today to apply for a bed because I will be homeless in four days. They had no beds. That is fine actually, I have a Van and might be able to take the heat and sleep in that until my next payment comes and I can head for the mountains. And there were plenty there that did not have even have a car.

In the last two years I have fought off dying from despair more times than I can remember.

So it is a weird study to have to do, proving that having money to survive lowers suicide rates.

But I have another solution; Yo, you people with money, slow down and hang out with people in your community. It is not that I need money, but solidarity and community. As long as people with money segregate themselves from the poor there will continue to be sadness and loneliness and deaths of despair.

i shall pray for you dear one. may you be happy, healthy, safe and with friends.

i am noticing an alarming increase in homeless people on the streets.

A previous entry here on the student loan crisis impacts on this in many ways. A study ought to be done on the psychological effects upon students of creating a system whereby indebtedness with compound interest and no bankruptcy faces any person in the US approaching college as a means to become employed, as it has done now lo, these many years.

I suspect this system affects not only the poor but the well off who have to somehow feel all right about it. And to my mind, compound interest trumps earned income, maybe even in many cases obliterates it.

The systemic indentureship must be stopped.

And your suspicions that such circumstances are deleterious to all members of society are confirmed in the work of “The Spirit Level”

https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/resources/the-spirit-level

Thank you!

A claim that causality can be deduced from correlation diminishes this laudable study. Or, am I missing something? Correlation does enable prediction. Isn’t that enough?

Has it come to this, then?

“If they would rather die,” said Scrooge, “they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.”

This is not a civilization.