It doesn’t look like there will be a happy ending for the over 100,000 CalPERS long-term care policy holders who are represented in the class action lawsuit, Wedding v. CalPERS. That doesn’t mean there’s a good outcome for CalPERS either. However, things should work out for the plaintiffs’ attorneys.

The bone of contention is that CalPERS approved an eye-popping 85% increase in premiums in 2013, hitting only the policies with the most generous payment features. The plaintiffs contend that these increases weren’t permissible and are seeking substantial damages.

The case has been grinding through the California courts since 2013. Judge William Highberger, in his decision from a June 10 trial, explicitly called on the legislature and state government to bail out the long-term care scheme.

Needless to say, this is a highly unusual step for a judge to take in a contract dispute. At a minimum, it signals an expectation that CalPERS will lose and lose big.

But CalPERS losing would be of no benefit to the policyholders as a whole (there could be some reallocation among them). It’s highly unlikely that the state will throw money at CalPERS. Unlike CalPERS’ pensions, the state has no obligation. The long-term care insurance plan was set up to be self-funded. So in a worst-case scenario, and “worst-case” looks all too likely, the relevant plans will be insolvent.

If the case results in a significant money judgment against CalPERS, and the judge’s body language is that that’s a probable outcome, the only place the funds can come from is the long-term care plans themselves. As we’ll discuss, that means that CalPERS would need to bankrupt the long-term care plan or take other measures to deal with their insolvency. Note that CalPERS has just put out a bid opportunity for an outside bankruptcy counsel.1

But expect CalPERS to drag things out. Defaulting on this scale would be a huge embarrassment. CEO Marcie Frost and General Counsel Matt Jacobs will do everything they can to try to kick this mess over to successors. The most likely course is for CalPERS to appeal and put off a formal bankruptcy or alternative (a runoff plan?) as long as possible.

Moreover, CalPERS does not appear to be taking Judge Highberger’s mission of pleading with the state and legislature for more money. The trial ended June 11. The judge asked the plaintiffs to prepare a draft ruling by June 19 with any comments by CalPERS due June 25. As you can see, the “draft” ruling was filed on July 1, although since the hearing was public, interested parties would have attended and anyone could also have ordered (and paid for) a trial transcript earlier. In other words, what happened in the trial was not a state secret, in particular Judge Highberger’s instruction to CalPERS to go to the Governor and legislature cup in hand.

Yet here it is, July 17, more than halfway between end of the trial and the date when CalPERS is next to appear in court, August 21. One would have to think if CalPERS had made any request to the legislature, or even briefed Senator Jerry Hill (chair of the Senate public pension/state employees committee) and Assemblyman Freddie Rodriguez (Hill’s counterpart) on the June trial, it would have gotten to the press by now.

So is CalPERS planning to poke a stick in the judge’s eye by doing nothing before August 21? Even this apparent failure to act as of yet, given that Judge Highberger signaled a sense of urgency, isn’t a good look.

Of course, any attempt to secure a rescue makes the probable insolvency of the long-term care plans more visible, which is something CalPERS no doubt is keen to avoid, Nevertheless, one has to assume CalPERS must through the motions, even though it’s an obvious non-starter, as we explain below.

Even forcing draconian spending limits on CalPERS’ staff (no more international travel or ice cream socials!) would make only a teeny weenie difference for the long-term care policies. CalPERS’ administrative budget comes overwhelmingly from other trust assets, namely its pension and other health care plans. Any savings from belt-tightening would have to be used for their benefit, so the result would presumably be a pro-rating. These long-term care plans, as much as they are important to the policy holders, simply don’t amount to all that much relative to the total assets CalPERS manages.

We’ve embedded his decision at the bottom of the post; you can find other major filings here.

But how did CalPERS get into this mess? The short version is that the long-term care insurance industry is top to bottom in trouble due to insurers launching the product in the 1990s without the foggiest idea how to price it, and got things badly wrong. And CalPERS made additional big mistakes all on its own.

The Long-Term Care Insurance Industry Debacle and CalPERS’ Additional Mistakes

In the 1980s and 1990s, insurers launched long-term care policies. They saw the opportunity to provide protection against the need of older people to foot the bill for nursing or at-home care. It proved to be a growth business, but not in the way that they had hoped.

The insurers, who had no experience, made a number of serious miscalculations. The first was in considerably over-estimating the number of people who would “lapse”, as in drop coverage, which would mean the monies they had paid in could be used for the benefit of those who continued to pay. Second was in adopting a payment model like that of the life insurance industry, specifically that policy-holders would stop paying premiums once they filed a claim. Since policy-holders can wind up receiving benefits for years (even before you get to “lifetime benefits”), this was a considerable sacrifice of potential premium income.

Third was these were long-term policies, and like life insurance and pensions, they depend on investment income. The insurers didn’t price in the protracted period of negative real interest rates that has been prevalent post-crisis.

Two additional decisions made this sorry picture even worse for most long-term care insurers. Many sold policies that promised no or low increases in premiums for the life of the policy. Industry leader Genworth sold many policies of this type. As the Wall Street Journal put it:

When sales of long-term-care insurance were ramping up in the 1980s and 1990s, companies thought they had found the perfect product for middle-class families—and that’s how they pitched it.

The annual premium was designed to hold steady until a claim was filed and premiums then halted, though the rates weren’t guaranteed. Many policies paid out benefits for life.

Finally, many also sold policies that promised lifetime benefits. In contrast to allowing for a fixed maximum policy amount, these policies capped only the amount that would be paid out per day or per year. This proved to be a catastrophically bad decision, particularly given the incentives.

If the insured has only a fixed maximum amount, they have reason not to start putting in claims until they really need to since they are at risk of exhausting the funds in their policy. By contrast, with a lifetime benefit, the insured will want to start drawing benefits as soon as possible, particularly since they would also stop paying annual premiums. As the Journal explained:

It turned out that nearly everyone underestimated how long policyholders would live and claims would last. For example, actuaries, insurers and regulators didn’t anticipate a proliferation of assisted-living facilities. And they assumed families would do whatever they could to avoid moving loved ones into nursing homes, holding down policy claims.

By the late 1990s, assisted-living facilities were widely popular. Especially at well-run ones, staff members looked after policyholders so well that they lived years longer than actuaries had projected.

CalPERS made all these mistakes and then some. Not only did it market its own “inflation protected” option hard, as well as offer a “lifetime” product, but appeared to get high on its belief in its investment acumen. It underpriced the polices compared to competitor offerings by about 30% and did not set up reserves either. One rationale was that its lack of its profit motive allowed it much more pricing room. Another reason for its considerable underpricing was CalPERS assumed much higher investment returns than private companies, out of a view that it made sense to put the policy premiums heavily in the stock market. CalPERS has since retreated to a more conventional insurance investment strategy. The resulting lowering of the return assumption has in turn worsened the underfunded status of these policies.

How the CalPERS Debacle Unfolded

In 1995, California passed legislation authorizing CalPERS to establish a long-term care program on a not-for-profit, self-funded basis. Not only eligible state employees, but even their family members could participate.

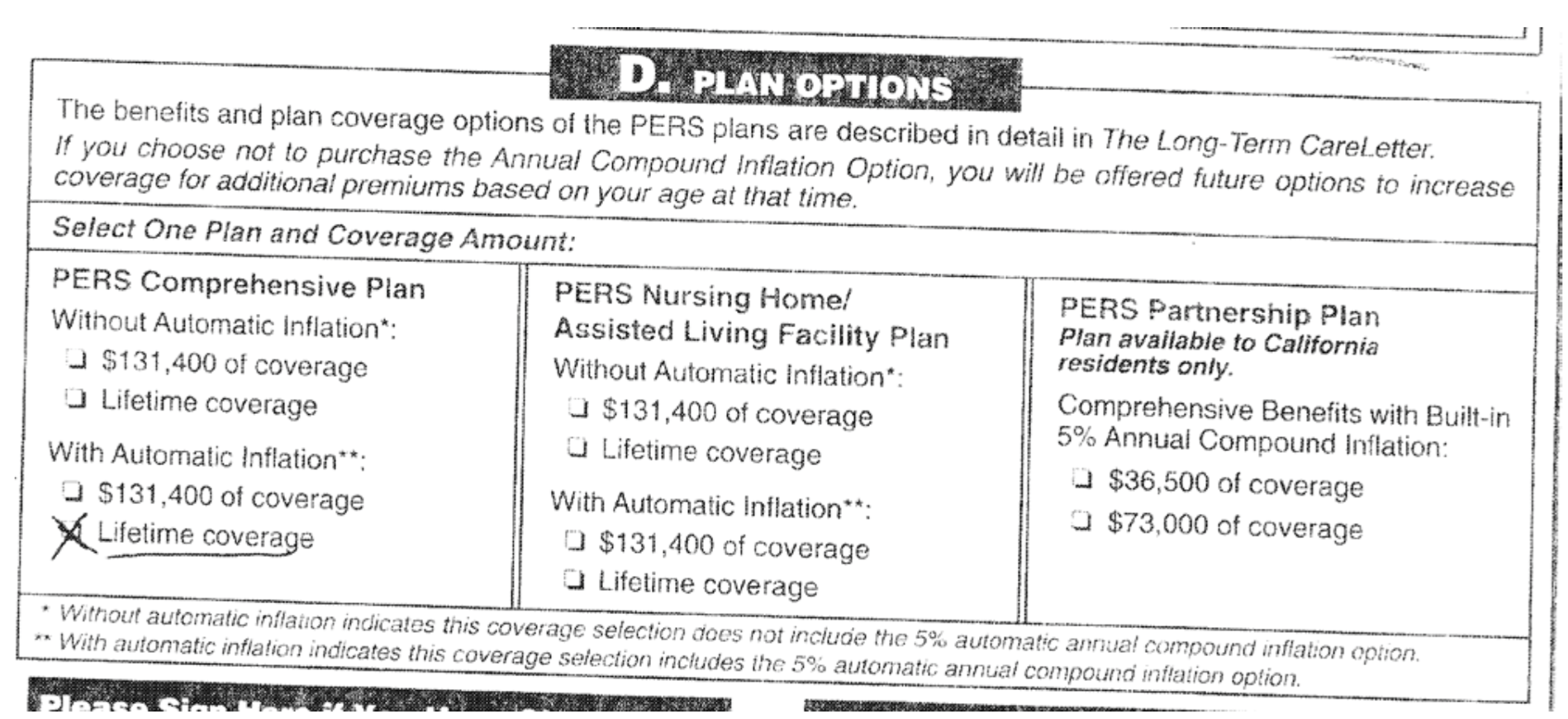

CalPERS allowed enrollees to choose from a variety of options. The lead plaintiff, Holly Wedding, opted for both “inflation protected” and the lifetime option. This was a popular combo:

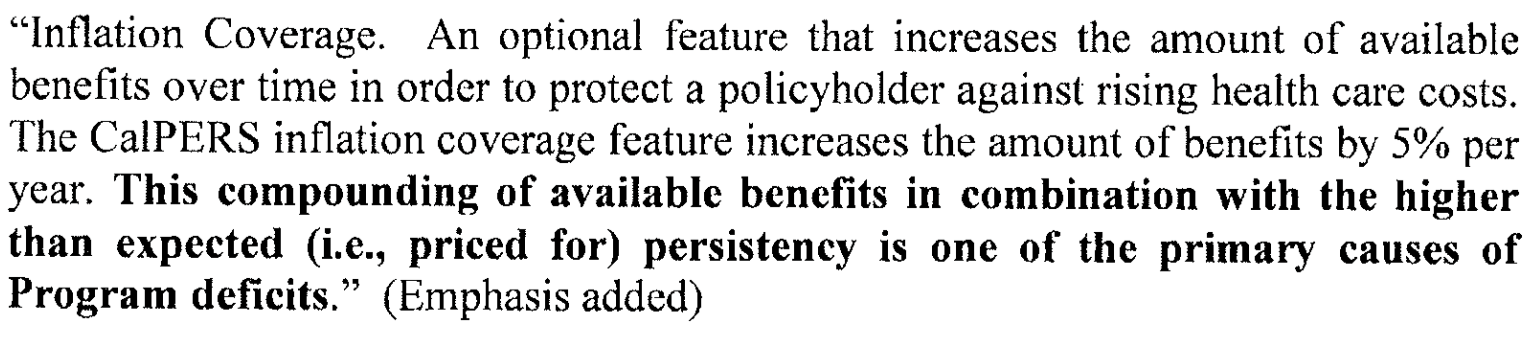

CalPERS had very aggressive language in its marketing materials regarding the inflation protection, which allowed for benefits to increase at the rate of 5% a year. If you look at the ruling embedded at the end of the post, the final page shows an “Exhibit A” which shows premiums staying flat over the 15 year time frame displayed in the chart. The judge, over CalPERS objections, also gave “considerable weight” to the testimony of Sandra Smoley, the Secretary of the California Health and Welfare Agency who had been tasked to CalPERS to assist in the marketing of the long-term care policies as “Honorary Chairwoman”. From his decision:

Ms. Smoley came away with the impression that persisted for 20 years that rates would not increase, and testified it was “very definitely” her understanding that “the plans with built in benefit increases will cost more on a monthly basis initially but you lock in a rate now that is designed to remain level over the life of the plan that won’t rise simply with age.”

This is particularly damaging to CalPERS. By virtue of being included in Judge Highberger’s ruling, it is now a finding of fact.

CalPERS apparently realized it had overpromised early on. Even though it had engaged Towers Watson to perform the initial actuarial work (Towers Watson has already settled with the CalPERS policy-holders for over $9 million), it brought in Coopers & Lybrand for a review in 1996. Coopers warned CalPERS that it had mispriced the inflation-protected policies, was likely to face “criticism that it had ‘low balled premiums” with the intent to increase them later, and would indeed need to do so. Despite receiving this report, CalPERS continued to tell policy-holders that premiums were “carefully and conservatively set” and “designed to remain level”.

CalPERS did increase rates, in 2003 (blaming it on the stock market) and in 2007 (“to stabilize the fund”). CalPERS attributed its 2009 increase primarily to the inflation protection feature:

In 2013, CalPERS announced it was going to implement an 85% increase, falling only on the holders of policies with inflation protection and/or lifetime benefits on “Comprehensive” and “Nursing Home” policies sold between 1995 and 2004. The CalPERS board and staff members stated that an advantage of this big increase was that it would get many of these policy-holders either to cancel their policies altogether, or forego the inflation protection and lifetime benefits features, which was the only way to escape the increases.

Key Issues in the Case So Far

In the interest of not over-taxing readers, I will greatly simplify (and hopefully not oversimplify) the discussion of some of the important issues in the case, in order to focus on Judge Highberger’s bailout request.

In his ruling (which included settling a cross complaint), the judge did agree with CalPERS that it could raise premiums, just not to cover any shortfall resulting from the inflation protection feature:

…..the Court also finds that CalPERS can implement across-the-board increases which include Inflation Protection insureds as long as the 20 reason for the increase is some matter of general applicability to all insureds; e.g., anticipated lapse rates of all insureds, longer than expected longevity of all insureds, longer duration on claim by all categories of insureds, and/or a further change in the discount rate.

This finding does not give CalPERS much relief. CalPERS has claimed that it would have needed to raise premiums by 67% (as opposed to 85% on the targeted group) to all long-term care policy-holders for the policy years in question to get to the same place it did in shoring up the fund. But the action CalPERS took, of not raising premiums at all on policy-holders who didn’t have the big ticket coverage features, looks like an admission that it was these features solely that are the cause of the insolvency the funds would otherwise have experienced.

And so far, CalPERS hasn’t offered any good explanations, save for ones along the lines of “We needed to raise rates to keep paying claims.” That falls well short of making a case for any reason other than the inflation protection feature at issue.

Maybe CalPERS is saving its ammo for trial, but this lame rebuttal does not look good.

On top of that, the plaintiffs may be able to do some pretty simple math and show the funds in question would be deeply underwater by virtue of the inflation-protection feature alone. That leaves CalPERS to try to ‘splain that no, a lot of other things were the real cause. Juries don’t like complicated explanations. If a simple computation of the cost of the inflation protection feature shows it renders the long-term care policies insolvent in a serious way, it’s hard to see how CalPERS can make any response, not just legally but practically.

Judge Highberger’s Futile Bailout Request

It is hard to understand where Judge Highberger is coming from. CalPERS has repeatedly stated in its filings that the long-term care policies were set up as self-funded. Unlike state employee pensions, there is no government guarantee. CalPERS also described, in some detail, the serious financial consequences to the long-term care policy holders if the appeals court did not reverse the trial court’s approval of class certification (it didn’t).

Judge Highberger repeatedly acknowledges that the state is not obligated to save CalPERS from the mess it created. For instance (emphasis ours):

While CalPERS did have the State Department of Insurance review the original contract and certain sales materials, CalPERS is not regulated by that agency and this Long Term Care Plan does not qualify for assistance from the California Life and Health Insurance Guarantee Association or the California Insurance Guarantee Association….

Many of the outcomes which Plaintiffs and their counsel desire, e.g., reinstatement of lapsed policies, are only possible via a voluntary compromise since the only outcome of this case if it is litigated to closure is a money judgment against CalPERS and/or injunction regarding its future course of conduct in handling price increases for Long-Term Care coverage.

Yet Judge Highberger nevertheless is pumping for the state to shore up this garbage barge:

The Court is issuing this [Draft] Proposed Statement of Decision at this time because the parties are urged to contemplate the settlement option, which will necessarily involve the State’s Executive branch, particularly the Department of Finance, and the Legislature. Since the enrollees in the certified class are all sUite and local employees, including teachers in the CalSTRS system (or close family members), there are many additional concerned stakeholders, including the labor organizations representing sUite and local employees and the statf retiree associations.

So Judge Hightberger wanted to get his ruling out pronto so that CalPERS would take it to the Governor and the Legislature and get a bailout….because a lot of people who signed up for policies would be hurt otherwise. That may be a nice sentiment, but Judge Highberger by now must have taken note that people in the private sector who bought policies in this time frame and have not yet put in claims are also being hit with huge premium increases.

In other words, electing to spend taxpayer money to rescue insiders and their family members when similarly-situated people outside the CalPERS plans are taking the premium hits does not sound like a winning political proposition. I can’t see the Governor or the Legislature being receptive.

And on top of that, despite Judge Highberger’s sense of urgency, his timing is off. The State approved the budget for the upcoming fiscal year on June 13.

So what was the basis for Highberger’s belief that the Executive would ask for funding and the Legislature would sign off? Not surprisingly, it’s thin:

Under the legislative authorization, this product was to be financially self-supporting with no subsidies from the taxpayers or the public employers, although Government Code§ 21664(f) provides that “[i]t is the intent ofthe Legislature to provide, in the future, appropriate resources to properly administer the long-term care program.”

Ahem, “administer” does not mean “fund plan plan benefits”. “Administer” means execute the managerial tasks associated with the discharge of a prescribed activity. This language could be argued to mean at most an appropriation of funds to help CalPERS to run the plan. And the Legislature may have contemplated “resources” to mean thing like lending Sandra Smoley, the head of the Health and Welfare department, to help market the policies.

This section describes what is apparently Judge Highberger’s other ground for hope:

An inability of this Ca!PERS plan to just claims will create an obvious default by an arm of the State in the fulfillment of its contract obligations. This, in turn, could seriously impair the credit rating ofthe State.

Putting on my Wall Street corporate finance professional hat, no. The lack of any guarantee or other financial obligation on the part of the state for the CalPERS means having CalPERS have to bankrupt or otherwise deal with the insolvency of its long-term care policies is of no consequence for the state bond rating. By contrast, having the state rescue these policies could even be seen as a negative, in that the state is taking on new liabilities analysts hadn’t known about, raising the specter that the state might engage in other costly acts of charity.

What happens down the road as CalPERS is trapped in the vise of the lack of good options? Not only does the inability to raise premiums to cover the cost of inflation guarantee seem to assure insolvency, but it’s also not even clear procedurally how CalPERS could restructure the plans absent bankruptcy or a similar process that allowed the parties to redo the agreement. And with so many policy options, meaning differently situated policyholders, coming up with any solution even if you could wave a legal magic wand, is daunting.

But if CalPERS is true to form, it will put off the day of reckoning as long as possible. That will have the effect of favoring policyholders who’ve already put in claims (as in are drawing benefits) over those still paying in on the fond hope that they’ll be able to get benefits in the future when they need them. So CalPERS’ inaction is already creating winners and losers, and the losers may well lose big.

____

1 In theory, this posting could be for attorneys to work with CalPERS on the bankruptcy of municipalities and government entities that have pension plans with CalPERS, but CalPERS has dealt with several of those already, including ones that were litigated, and didn’t seek bankruptcy advice.

00 Wedding v. CalPERS July 1 2019 filing

> the number of people who would “lapse”, as in drop coverage, which would mean the monies they had paid in could be used for the benefit of those who continued to pay.

I recall reading about McDonald’s insurance plan, where managers would fire people at the (six-month?) point they would receive coverage. The McD’s plan required vestment, if you wanted a job, and the manager had incentive to fire, to keep their job and coverage.

But that’s small-circle, and can be kept in-house. This is big-circle, and is entwined with the world. The only way to ensure a stream of suckers to lapse would be to ensure there is a desperate pool, which means leveraging the immense weight of CalPERS to ensure austerity for the general populace.

I can’t get myself to believe somebody didn’t run the numbers. Remember the oil industry studies on climate change from the 1970’s. They knew, they just suppressed and kicked the can down the road, ibgybg. Towers Watson has already settled – settled for what, deliberate incompetence? I thought actuaries were supposed to be smart.

@Steve H.

July 17, 2019 at 7:37 am

——-

I was selling life and health insurance back in the ’80’s when LTC policies first hit the market.

As Yves says in the post, the insurance companies (and CalPERS) did, in fact, run the numbers, even hiring actuarial experts to advise on pricing. The problem was that this was a unique product with no claims history or lapse history on which to base the original cost assumptions. They were all essentially driving blind.

At the present time almost every single insurance company that sold LTC policies is operating that segment of business in the red. Their cost assumptions and projected lapse rates have been shown by experience to have been wildly unrealistic.

The bad assumptions about lapse rates did not take into account how much people feared the cost of nursing home care. Monthly cost-of-care was already high in the ’90’s and like much of the medical industry, the inflation in cost has far exceeded the general rate of inflation. Policyholders are loathe to give up their coverage because of this.

This rapid increase in monthly cost for such care is the other main assumption that failed. CalPERS inflation adjustment of 5% per year was pretty much industry standard for inflation-protected policies. Facility operators were far more aggressive in raising prices.

Wow. Thanks for this post. Long Term Care ( LTC ) policies were started in good faith or at least hope, imo, by insurance companies who thought they understood LTC insurance actuary models when, in fact, they did not. All the policies I’m familiar with have either raised rates repeatedly and steeply almost every year for the past 5-10 years, or they have been bought up by larger insurance companies who then changed the premium structure or stopped selling the insurance, or they have gone bankrupt and out of business. CalPERS is doing what almost all other insurance company LTC plans have done, so CalPERS isn’t alone in this.

However, what sense did it ever make for a state pension fund to start its own LTC plan ? Yes, a pension is a form of insurance for income replacement in retirement. That’s a different model than LTC insurance. In fact, I’m not sure any insurance company has a good actuarial model for LTC insurance. So rates keep going up, by a lot; coverage keeps decreasing; getting some companies to honor terms of the contract is getting harder. 20-30 years ago buying a LTC policy from a reputable insurance company was considered a no-brainer. For many years companies did honor in full the policies they wrote without premium hikes or only modest premium hikes, until eventually the companies started either going broke or making big changes in premiums and coverage.

Why did CalPERS jump into that business 20 years ago? (And why does it now want to jump blindly into hand-money-to-hedgefunds-just-as-hedgefunding-is-starting-to-slide ?) CalPERS investment problems seem to go back a lot farther than I realized.

Thanks for your continued reporting on CalPERS, pensions, and PE.

Today’s post is a terrific primer on the LTC debacle. I remember being hustled to buy this plan 25 years ago. I thought at the time that it was an under-priced scam that would collapse by the time I needed it.

My reading of Government Code section 21660 and following is that 25 years ago the Legislature directed the CalPERS board to design a LTC plan or to secure a LTC plan on the open market and sell it to members. CalPERS had no idea how to price and sell insurance, and it is rightly the State of California that should be on the hook, not the pension trust.

Remember, this is the same Republican-led state government under Governor Pete Wilson and Senate Speaker Jim Brulte that forced the utility companies to divest of their power-generation infrastructure and to buy power at “market rates” from Duke, Calpine, Enron, et al, while continuing to deliver it at regulated prices to customers.

On page 16, Judge Highberger clearly relishes pouring a bucket of offal and excrement over the head of Sandra Smoley, Secretary of the California Health and Welfare Agency from 1993 to 1999, appointed by then-Governor Pete Wilson. He describes Smoley’s testimony in the suit as a “declaration against interest” by CalPERS. Smoley was the one who was hustling the plan to CalPERS and to the members on behalf or the Wilson administration.

To call Wilson, Smoley, and Brulte idiots is an insult to idiocy.

New CalPERS motto: IBG-YWYWG

I’ll Be Gone – You’ll Wish You Were Gone

Somewhere in Sacramento, a blue ribbon commission is undoubtedly working on a CalPERS Put. /s (or at least I hope that is /s)

an aside re Enron, Duke, el al and California’s locally owned power-generation divestments: That worked out well…not. Ask Grandma Millie.

https://www.sfgate.com/business/article/Enron-agrees-to-pay-penalty-States-1-5-2655273.php

Yet again I can only (completely uselessly) offer sympathies to the affected residents of California. It costs nothing and it is, like the LTCP (Long-Term Care Plans), worth nothing — or likely to be. At least the judge had the decency to try to nudge CalPERS via moral suasion and the Court of Public Opinion. An admirable gesture, but since it is CalPERS we’re talking about here (again… you could have a bog entirely devoted to CalPERS failings, if you had the strength to publish it), he’s whistling in the wind.

There’s several lessons to be drawn from all this, the important ones are in the post, but a couple I’d like to expand for readers with capacity for more miserable reading.

The first is, beware, poor member of our dismal neoliberal societies, of anything and everything in the realm of financial services. Unfortunately, and there is no real option to this, you have to check into all aspects of every financial product you consider. Sometimes it’s obvious what you have to look at, but at others, even seasoned experts find it difficult. But you have to do your best. One of the biggest mistakes, which isn’t the fault really of the customer, is trusting brand. If I was to offer, via these learned pages, “Clive’s Twilight Care for the Bewildered Cash Plan”, you might be more than a little sceptical about things like how well capitalised my scheme is, what protections were available if I defaulted, what redress might be available if my product wasn’t suitable for you but I’d sold it to you anyway — and so on.

But how many retail purchasers of CalPERS good-for-nothing plan relied on seeing — and taking undue comfort from — “CalPERS” appearing as the provider? Quite a few, I’d wager. And I also suspect that during the sales process, no serious effort was made to distance CalPERS pension provisions (which are state-backed) from the Care Plan (which, as has been shown, demonstrably isn’t). Just because there’s a fancy (or seemingly-reliable) name on the product does not mean they actually have to have anything to do with that product.

The second point adds a little extra detail to the socialising (or otherwise, as here) the losses of the scheme. This movie has had so many sequels and plot rip-offs, it’s simply untenable — as Yves correctly pointed out — that any appeal for state aid is going to get anywhere. It’s tempting that the judge — conscious as they would be that their ruling will uphold one claimant’s argument but then immediately plunging the scheme into an almost-inevitable solvency death-spiral — might want to try to fix the problem he’ll know he (or his judgement) is a trigger for. But no way is this going to go anywhere.

For a worked example of how difficult it is — even if the state steps in to try to make good losses on a financial product — to actually deliver what they judge is intimating he’d like to see, the UK’s Equitable Life scandal is probably the reference authority. Assuming by some ridiculous circumstances the state did opt to step in and offer assistance to the policy holders, the administration of this is a nightmare. Obviously, where public funds are concerned, you can’t just pay out to any policy holder who shows up and makes a claim for compensation. You have to make them “whole” (by whatever definition “whole” ends up being decided upon, that itself isn’t especially straightforward). But you can’t allow unjust enrichment.

So each claim has to be looked at (what the policyholder was told at the point of sale, what subsequent information they could have or should have reasonably been expected to be aware of concerning the policy, what the payments of the benefits under the policy are requested by the policy holder, whether these claims are within the policy’s schedule, whether they are fair or excessive, whether the claim is being made by the original policy holder or by an estate of a deceased person, how far back you want to go in mopping up historic claims — on and on and on…). This itself is a potentially huge drain on the public purse — for nothing more than administration. “Administration” might sound like it is trivialising the requirement here, but it is anything but. Maladministration, which is easy to end up with and a significant risk, is just going to make a bad situation worse.

I’ll say this for CalPERS, at least they’re consistent. When they make a mess, it’s not a trivial one, it’s got all the bells and whistles.

“does not mean they actually have to have anything to do with that product.” And even if they do, it may well not matter.

Ah, Equitable Life. I fondly remember The Guardian urging readers to open With Profits policies there, so that they’d pocket a handy sum when the company demutualised. I don’t suppose anyone sued the Guardian.

As for the general problem of “Care” insurance there is no general answer. It will cost a fortune, potentially, but afflict only a minority of each age cohort. The logical answer is insurance but that seems to be far too tricky to make work.

Woe, woe, and thrice woe.

I was talked into taking out policies with Equitable Life in 1987, and as the ‘World’s oldest life assurance company’ redolent with the boring solidity of the member’s lounges in London’s most exclusive clubs, the scent of Masonic influence, the implication that ‘the best’ entrusted it with their millions and the solid, sensible, still Victorian-oriented hands on the tiller, it seemed a good bet.

It wasn’t until 1990 that I actually read the small-print and even though I’m no financier what I saw made alarm bells ring that caused me to discontinue paying my premiums.

As a result I didn’t lose out too badly when the firm went under, but as another result I’ve never trusted any other business pushing ‘financial’ solutions.

A business currently pushing its offering here in New Zealand – LifetimeIncome – will take a capital sum off you and pay a ‘guaranteed’ monthly income for the rest of your life, based on your present age. In my case, 68, it’s at 5% pa. It’s paid from income plus return of capital ‘if necessary’ but if your capital is exhausted the payments will be continued by ‘insurance’.

I guess they’re banking on enough ‘clients’ dying still with capital in the fund to cover the others, but with returns being what they currently are, their no-doubt generous costs and fees plus the cost of the ‘insurance’ premiums, your capital isn’t going to last long and I wouldn’t trust any insurance company to meet its obligations any further than I could throw it’s MD’s expense account ledger. And your promised income isn’t inflation-proofed unless you opt for a much reduced return.

Sometimes you don’t even have to read the small-print to start the alarm-bells ringing.

You seem to be describing a conventional annuity, specifically a level annuity. Why on earth are you frightened of it? They have been common in Britain for … I dunno, a couple of centuries perhaps. Or longer: Jane Austen treats them as commonplace. None has failed in living memory, or maybe none has ever failed.

Even with Equitable Life it was only the With Profits annuities that got into trouble: the level annuities were all paid as promised.

I expect you meant blog, but arguably better this way : – )

Obviously when Judge Highberger was quoting Government Code§ 21664(f) which states “it is the intent of the Legislature to provide, in the future, appropriate resources to properly administer the long-term care program.” he forgot to check the addendum. If he had he would have found that the term “in the future” is explained as being when an interdepartmental committee is set up with fairly broad terms of reference so that at the end of the day they’ll be in the position to think through the various implications and arrive at a decision based on long-term considerations rather than rush prematurely into precipitate and possibly ill-conceived action which might well have unforeseen repercussions. A decision will then be made at the appropriate juncture, in due course, in the fullness of time…

Theresa May may be out of a job but CalPERS should really consider hiring her. After all, she has a proven history of being able to kick cans down the road again and again and she would fit in well with CalPERS trying to drag things out until the whole structure goes belly up. They seem to have been copying her tactics over the past few years anyway. Not sure how she would go in a Burgundy dress though.

Washington State’s Public Long-Term Care Program Is On The Verge Of Becoming Law

Back in the 80s and 90s when LTC was first designed, it was designed to fit the “free market” we had and envisioned. It relied on much the same plan as other medical facilities which must make a profit. And in order to make a profit, a certain amount of demand was needed. So the quasi monopolistic medical industry maintained its pricing by maintaining its usual tactic – scarcity. Some of that backfired into assisted living. Not the least because LTC policies were outrageously expensive. To learn that CalPERS got involved is scary, because how many other state pensions funds did the same? State and Federal government will be running flat-out to catch up to reality. The joy of another neoliberal market debacle.

Just at the time when Private Equity companies are sharpening their knives in anticipation, too. What a coincidence.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2019/06/28/private-equity-firms-are-taking-over-long-term-care-insurance-policies-what-will-it-mean-for-policyholders/#56b892893967

(tin foil alert: maybe CalPERS wants to throw money at hedgie or PE in hopes they’ll buy the basically insolvent CalPERS LTC plans and get them off CalPERS books. )

Thank you for that article. Had not seen it.

YIKES!!!

I wonder if this project was one of CalPERS’s better-managed ones?

If so, Ms. Frost should probably keep her powder dry. She – or her successor – is likely to need much more money from the state to solve much bigger problems at CalPERS itself.

The state is already providing mini-bailouts to its pensions in the form of “pre-fundings”. Then CalPERS goes out and touts the improvement in its funded status as if the staff, as opposed to the munificence/self interest of the state, were responsible. Nice!

What a bunch of spoiled, entitled, little a**holes!

Could someone help me understand LTC insurance better?

As I read articles like these, the problem, as I understand it, is that people draw benefits for a lot longer than the plans were designed to cover, and that inflation protection is a double-whammy.

Every plan that has been pitched at me recently claims that most people only need the coverage for less than 3 years. In fact, I haven’t seen a plan recently that offers more than 3 years coverage. That seems to be contradicted by the article, and others like it. Is it just a small minority who draw benefits for a long time, or when they say most people, are they saying anything over 51% is ‘most people’?

@Jon Paul

July 18, 2019 at 6:36 am

——-

You actually have the right idea, see my post above.

The reason you only see 3-year policies nowadays is that the insurance companies have over 30 years of experience with the actual lapse rates and cost inflation, as well as the propensity of policy holders to file claims. Pricing 3-year policies is far easier and more accurate than projecting life expectancy and medical industry inflation for lifetime policies.

If I have a lifetime benefit, I’m gong to file a claim as soon as I enter a qualifying facility (policies define those differently). OTOH, if my policy has only a three year benefit, I’m more likely to attempt to use other resources, if available, before filing a claim. In general, costs go up as the level of care increases from, e.g., assisted living to full nursing care. I would want to save my benefit for when I needed it most.

This is why I have shied away from LTC and deferred annuities altogether. Way back when I first started looking at these things in the 1990s, it wasn’t clear to me that there was a good model to insure solvency of the insurers 30 to 50 years later when I might need the insurance. It looked to me like a rabbit hole to throw my money into with a only a medium probability of getting it back later if I needed it.

If I want to use insurance products in retirement, I plan on looking for immediate ones that don’t have a big delay in getting benefits so I can evaluate the insurance company financial condition at that time. For things like LTC, the equity in the house will be a major part of self-insuring for that.

I purchased two LTC policies from GE 20 years ago. At the time, my guiding principle was to confine my choice of insurers to only those companies which were both currently healthy and had a reasonably long history in the particular risk they were insuring.

GE fit the bill in 1998.

However, after the 2007-09 crisis, the Genworth spin-off and the under pricing of risk alluded to by Yves, its quite clear my choice of insurance company did not measure up to my standard.

And so it goes.

GE has given a financial guarantee to the Chinese buyer of Genworth. My mother put in a claim and they’ve been fine. They even keep chasing her to re-send a form she didn’t sign for one set of payments so she gets her $. Flip side is she was told she wouldn’t have to keep paying premiums once she put in a claim, but Genworth apparently got approval from the Alabama regulator. She has to pay, but at least at a way lower rate than before.

But if you are younger, yes, you are at risk the money won’t be there.

This article includes a good deal of speculation, but the enthusiasm of the judge for getting a bailout from the state seems to suggest that the situation is serious. It almost makes one wish for some failing ADLs, so benefits could be delivered now, before it’s too late. A rather perverse “reward” for a lifetime of public service.

Thanks for a great post. One of the key comments here is “the LTC plan was intended to be self-funded.”

When a plan is self funded, then its premiums will be experience-rated. If the actuarial experience is bad, the premiums will increase.

This is a relevant distinction in the current health care debate. Right now, if Medicare runs a deficit we basically ignore it, and raise taxes where possible.

But the proponents of a new ‘public option’ are either ignorant or disingenuous about experience rating, They do not discuss what will happen if claims exceed projections.

Meanwhile, long term care should be funded with social and not private insurance.