By Lambert Strether of Corrente

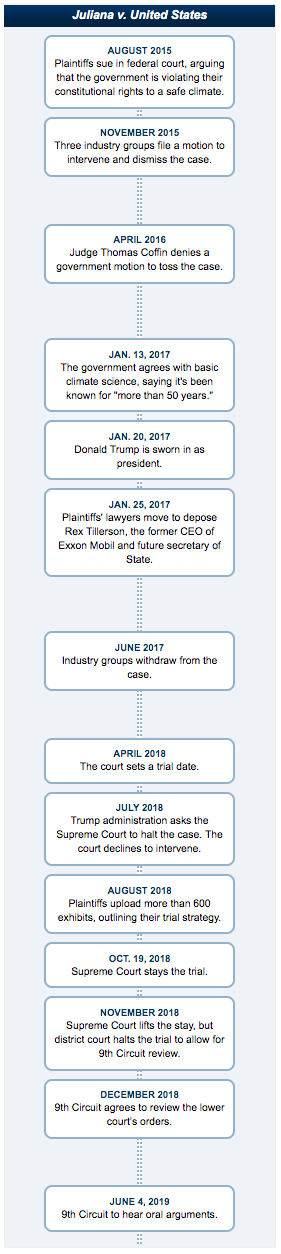

Juliana v. United States is a big and complicated case that has now advanced through two administrations. The original complaint was filed in September 2015; Judge Ann Aiken of Oregon district court rejected the government’s motion to dismiss the case in November 2016. At right is a timeline of the docket from E&E News which I am not going to go through, although it does show the twists and turns the plaintiffs have had to go through.

(I don’t know why the docket has Coffin in April 2016, and not Aiken in September 2016, but it’s complicated…. )

The American Bar Association, in “Can Our Children Trust Us with Their Future?,” describes the scale of the case and the stakes:

The 2016 ruling in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana v. USA is one of the greatest recent events in our system of law. (See Opinion and Order, Case No. 6:15-cv-01517-TC, US District Court for Oregon, Eugene Division. Anne Aiken, Judge, filed 11/10/16.) A group of children between the ages of eight and nineteen filed suit against the federal government, asking the court to order the government to act on climate change, asserting harm from carbon emissions. The federal government’s motion to dismiss was denied. Although I am not involved in the case, I am a lifelong environmentalist, and I teach environmental law (to non-law students). This case is a shining example of what law can be. This case gives me hope that we will not continue to cooperate in our own destruction, and future generations will be able to rely on us to uphold the spirit of the law and purpose behind government.

(Interestingly, Juliana is not the only such case brought by children.[1]) In an interview with the Real News Network, “Why A 20-Year Old Climate Activist is Suing the Federal Government“, Vic Barrett, one of the plaintiffs, sums up the theory of the case[2]:

So Juliana v. United States is a lawsuit that’s being sponsored and facilitated by Our Children’s Trust, which is a nonprofit organization in Eugene, Oregon, that’s been working on atmospheric climate litigation to try to deal with the climate crisis for a while. So our lawsuit was filed in August of 2015, with 21 plaintiffs from all over the country that each have their own complaint, as part of a large declaration that gives a standing to sue the U.S. Federal Government. And basically, we’re asserting that the U.S. Federal Government has known since 1960 that climate change could be potentially disastrous. We have proof from administrations going back all the way to the Johnson administration, saying that they knew climate change could be an issue and they knew that fossil fuel infrastructure was causing it. And the U.S Federal Government still chose to take direct action to continue to perpetuate the fossil fuel industry and the U.S. fossil fuel economy that we have.

And we’re asserting that by taking that direct action, they’ve disproportionately put the rights of young people at risk, and the rights of life liberty and property as promised to us in the Constitution. And so, what we’re looking for our in our case is for the court system to mandate that the legislative system and the executive system have to work together in order to come up with a plan that would draw down carbon emissions to a point that’s sustainable for human life, and do what we can to bring the global temperature down to at least one and a half degrees Celsius.

(So they have demands. That’s good!) We are now awaiting the results of the final item on the docket, the oral arguments held before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on June 4 (video). Grist describes the situation as of July 22:

Right now, we’re waiting for a decision from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals on whether the case can move forward to the district court, effectively restoring the case to where it was before the Trump administration’s latest appeal knocked it off course. That appeal was just one of the many roadblocks the case has faced since it began in 2015 — the first, an attempt by the Obama administration to toss it out completely. In the ensuing years, the case has bounced between the Oregon District Court, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and the Supreme Court, where the Trump administration has filed multiple motions and petitions to delay and stop it.

It’s looking pretty good for the kids right now — courts typically allow reasonable cases to go to trial, so parties can present their full slate of legal claims, according to University of Oregon environmental law professor Mary Wood. But it’s unclear when we’ll get that decision. It’s been over a month since the hearing in Portland, and there’s really no upper limit on how long it could take, although the court is likely to take the particular urgency of the case into account.

In this post, I won’t go through all the aspects of Juliana in detail. Instead, I’ll look at climate change litigation internationally, which shows the powerful effect for good that success in Juliana could have. Then I’ll turn to two issues in Juliana: The standing of the plaintiffs, and the public trust doctrine, one of the claims for relief presented in the original brief. Before concluding, I’ll turn to one of the litigators on the topic of what the Federal government knew and when they knew it (spoiler: Everything, since forever).

Status of Climate Litigation Internationally

Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot

The Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment tracks climate change litigation, and divides the cases into two buckets. From Joana Setzer and Rebecca Byrnes, “Global trends in climate change litigation: 2019 snapshot“:

Climate change litigation cases can be divided into two broad categories:

- Strategic cases, with a visionary approach, that aim to influence public and private climate accountability. These cases tend to be high-profile, as parties seek to leverage the litigation to instigate broader policy debates and change.

- Routine cases, less visible cases, dealing with, for example, planning applications or allocation of emissions allowances under schemes like the EU emissions trading system. These cases expose courts to climate change arguments where, until recently, the argument would not have been framed in those terms. Routine cases might also have some impact on the behaviour and decisions of governments or private parties, even if this is incidental to their main purpose.

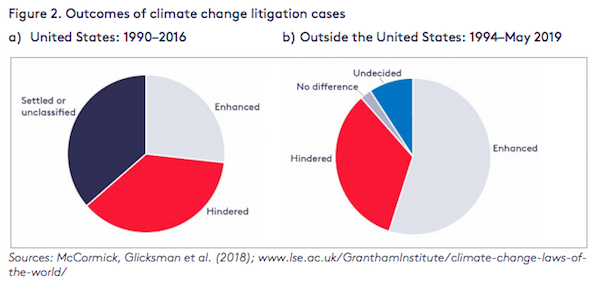

Clearly, Juliana is strategic; I’m really including that passage to underline that routine cases like suits against pipelines, oil or gas terminals, “train bombs,” etc. play an important role, especially in “keeping it in the ground. Grantham also looked at the outcomes of climate lawsuits worldwide between 1990 and 2016, summarizing the results in the following chart:

(“Hindering” means that efforts to halt climate change are hindered; “Enhanced,” the reverse.) So you can see that the United States is, by global standards, exceptionally poor at “enhancing” the climate. Juliana, by mandating “that the legislative system and the executive system have to work together in order to come up with a plan that would draw down carbon emissions to a point that’s sustainable for human life” would reverse that unfortunate trend.

Juliana: Standing

When my friends and I were fighting the landfill, standing was an enormous problem; as it turned out, only “abutters” with property in contact with the landfill had standing. (That is, absurdly, I could not sue because, when the landfill liner failed, as landfill liners inevitably do, my watershed would be poisoned.) The plaintiffs in Juliana, however, seem to have achieved it. From The New Yorker, in “The Right to a Stable Climate Is the Constitutional Question of the Twenty-first Century“:

Judge Aiken had found that the plaintiffs had standing to sue because they had demonstrated three things: that they had suffered particular, concrete injuries; that the cause of their injuries was “fairly traceable” to the government’s actions; and that the courts had the ability, at least partially, to remedy these injuries. On the first two parts of standing, the government’s case is weakening by the minute, owing especially to the growing body of attribution science—studies published in peer-reviewed journals that directly link extreme weather events, such as huge hurricanes and raging wildfires, to climate change. “Evidence to meet the standing burden has gotten much stronger,” Ann Carlson, an environmental-law professor at U.C.L.A., told me.

However, in another part of the forest, in a parallel case, another judge disagrees. Forbes, “Children’s Crusade For Judicially Managed Climate Regulation Stalls In Federal Court“:

In Clean Air Council, an activist group and two unnamed minor children claim that actions and inactions by the federal government have deprived them of their Fifth Amendment right to a stable climate. They also argue that the government failed to uphold its common-law public-trust duty to protect the atmosphere and other resources from climate change. These allegations and novel legal theories mirror those advanced successfully in Juliana v. United States, in which a U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon judge denied the Obama Administration’s motion to dismiss.

Before evaluating the substantive issues, however, Judge Diamond held that neither the activist group nor the children had Article III standing to sue. The standing doctrine, he rightly explained, is an essential check that prevents “‘the judicial process from being used to usurp the powers of the political branches.'”

Judge Diamond then examined the individual children’s standing arguments, finding that their alleged physical harms (but not their anxiety over climate change) were “concrete” and “particularized.” Those harms were not, however, “actual or imminent” as required under the law. Their alleged harm, the court explained, is predicated on a “contingent chain of events” that render the children’s claims “at best, a less than certain prediction.”

Not even playing a lawyer on TV, I can’t speak to the merits of these positions. However, my feeling is that standing is often a very useful escape hatch for a court that does not want to rule on a difficult or challenging case.

Juliana: Public Trust Doctrine

Violation of the public trust doctrine is the fourth claim for relief in the plaintiff’s original brief. That claim reads in relevant part:

Plaintiffs are beneficiaries of rights under the public trust doctrine, rights that are secured by the Ninth Amendment and embodied in the reserved powers doctrines of the Tenth Amendment and the Vesting, Nobility, and Posterity Clauses of the Constitution. These rights protect the rights of present and future generations to those essential natural resources that are of public concern to the citizens of our nation. These vital natural resources include at least the air (atmosphere), water, seas, the shores of the sea, and wildlife. The overarching public trust resource is our country’s life-sustaining climate system, which encompasses our atmosphere,waters, oceans, and biosphere. Defendants must take affirmative steps to protect those trust resources.

309. As sovereign trustees, Defendants have a duty to refrain from “substantial impairment” of these essential natural resources. The affirmative aggregate acts of Defendants in the areas of fossil fuel production and consumption have unconstitutionally caused, and continue to cause, substantial impairment to the essential public trust resources. Defendants have failed in their duty of care to safeguard the interests of Plaintiffs as the present and future beneficiaries of the public trust. Such abdication of duty abrogates the ability of succeeding members of the Executive Branch and Congress to provide for the survival and welfare of our citizens and to promote the endurance of our nation.

310. As sovereign trustees, the affirmative aggregate acts of Defendants are unconstitutional and in contravention of their duty to hold the atmosphere and other public trust resources in trust. Instead, Defendants have alienated substantial portions of the atmosphere in favor of the interests of private parties so that these private parties can treat our nation’s atmosphere as a dump for their carbon emissions.

(The Posterity Clause of the Constitution is in the Preamble: “to ourselves and our Posterity.”) That’s the stuff to give the troops! Here is a lawyerly disquistion on the public trust doctrine from the American Bar Association, “Climate Change Litigation: A Way Forward“, with citations and everything:

Public trust arguments are based on a long-established doctrine from Roman times carried forward in common law jurisprudence for generations. The doctrine asserts that natural resources are the birthright of the public and the government is responsible for preserving the resources for this and future generations in the same way a trustee must preserve a trust. See Brief of Amicus Curiae Law Professors in Support of Plaintiffs-Appellees’ Answering Brief at 5, Juliana v. United States, No. 18-36082 (9th Cir. Mar. 1, 2019). Cases relating to public resources such as water, public access, and fisheries and wildlife have successfully employed this principle. See Richard M. Frank, Symposium, The Public Trust Doctrine: Assessing Its Recent Past & Charting Its Future, 45 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 665, 671–80 (2012). Federal and state courts have granted public trust claims. See id. at 673. Using the same reasoning, atmospheric trust litigation claims the government has a duty as trustee to protect the atmosphere, air, and a livable climate. Individuals like the Juliana plaintiffs use public trust theory litigation to argue that the government has a duty to act in the public interest by protecting the trust corpus and fulfilling the government’s role as trustee.

(The whole article is worth a read, and has more on standing and “suspect classes.”) Here is the government’s response:

The district court should have dismissed Plaintiffs’ public trust claim for three independent reasons. First, any public trust doctrine is a creature of state law only, and it applies narrowly to only particular types of state-owned property not at issue here. Consequently, there is no basis for Plaintiffs’ public trust claim against the federal government under federal law. Second, even if the doctrine had a federal basis, it has been displaced by statute, primarily the Clean Air Act. Finally, even if any such doctrine had not been displaced, the “climate system” or atmosphere is not within any conceivable federal public trust.

I must say that the public trust doctrine seems so clearly right to me that the government’s response reminds me of Monty Python’s The Argument Clinic: “No, it isn’t.”

What Did They Know and When Did They Know It?

CBS reporter Steve Croft, in “The climate change lawsuit that could stop the U.S. government from supporting fossil fuels,” interviews Julia Olson, an Oregon lawyer, and the executive director of the NGO, Our Children’s Trust, which initiated Juliana:

“[Olson] began constructing the case eight years ago out of this spartan space now dominated by this paper diorama that winds its way through the office.”

OLSON : So this is a timeline that we put together… [D]uring President Johnson’s administration, they issued a report in 1965 that talked about climate change being a catastrophic threat. Every president knew that burning fossil fuels was causing climate change.

Fifty years of evidence has been amassed by Olson and her team, 36,000 pages in all, to be used in court.

OLSON: Our government, at the highest levels, knew and was briefed on it regularly by the national security community, by the scientific community. They have known for a very long time that it was a big threat.

KROFT: Has the government disputed that government officials have known about this for more than 50 years and been told and warned about it for 50 years?

OLSON: No. They admit that the government has known for over 50 years that burning fossil fuels would cause climate change. And they don’t dispute that we are in a danger zone on climate change. And they don’t dispute that climate change is a national security threat and a threat to our economy and a threat to people’s lives and safety. They do not dispute any of those facts of the case.Steve Kroft: So you’ve got them with their own words.

OLSON: We have them with their own words. It’s really the clearest, most compelling evidence I’ve ever had in any case I’ve litigated in over 20 years.

30,000 pages. It looks like there’s a reason Juliana has survived as long as it has.

Conclusion

If we have any lawyers, and especially any climate change lawyers, in the house, I’d very much like to hear of any corrections or additions!

NOTES

[1] From the National Geographic:

When young people in the Netherlands sued their government for inaction on climate change, they unexpectedly won. In a decision noted for its bluntness, the court ordered the government to curb carbon emissions 25 percent by next year.

Another ground-breaking success emerged last year in Colombia, where 25 young people won their lawsuit against the government for failing to protect the Colombian Amazon rainforest. The court concluded that deforestation violated the rights of both the youths and the rainforest and ordered the government to reduce it to net zero by 2020.

And a seven-year-old girl in Pakistan gained the right to proceed with her climate change lawsuit on its merits—establishing, in a first for Pakistan, the rights of a minor to sue in court.

The Dutch case has became the model for similarly fashioned lawsuits in Belgium, Ireland, and Canada, and it has inspired other climate cases in countries as far flung as Uganda, New Zealand, Australia, and Norway. The Colombia case has had a similar impact. When the youths there won their case, Boyd says, “Let me tell you, there were lawyers in 100 other countries saying: how can we emulate that decision? We’ve never had such a globally connected system.”

[2] Distressingly, Barrett also says:

And I think with the climate crisis, what’s particularly like damning about it all, is that people of color, black people, have always been stewards of the earth, they’ve always been stewards of nature and have always taken care of the earth and what we have around us. And so, the fact that these systems, these white supremacist systems, have turned the earth against us is really what motivates me to keep doing the work and keep tapping into my ancestry and keep thinking about who I am and why I’m doing this.

A moment’s thought will show that if China is part of the climate change problem, then white supremacy is not the controlling factor.

Are the court rulings enforceable? For example, it’s been a few years since the original court ruling in the Netherlands. What progress has been made to the requirement of “greenhouse gas reductions of at least 25% by 2020” (based on 1990 levels).

Will the court order the lights be turned off? It is not going to happen.

My thought, too. I suspect that even a complete win in Juliana would have little effect. The legislature can simply ignore it, and the executive probably would, too. Are the courts going to pick that kind of fight with all the rest of the government?

It’s still arguably worth doing, because a judgement would move the “Window.”

I guess it depends on the legal jurisdiction, but I would imagine the enforceability comes from ‘second order’ challenges.

So while the first legal decision can’t be enforced, it can be used as the basis to legally challenge, for example, a permit being granted to a new coal fired station on the basis that granting it is contrary to the higher courts decision. In other words, it sets a significant legal obstacle to every ‘implementation’ decision of a public body, from zoning to infrastructure to development permits, etc.

Yes, and a favorable finding could set a precedent for action against oil and gas companies for potential harm caused by fracking.

Thanks for this Julianna update, Lambert, and your thinking on the lawsuit and it’s prospects. It will be very interesting to see Olson’s timeline, and the evidence she has collected. I had no idea it went back as far as Johnson. “Stuff to give the troops” indeed!

For something of this scale of course we’ll eventually need another nuremberg.

oi! its

that bugs me when i do that, sorry

Distressingly, Barrett also says:….

Nice to know that only white people are extracting crude oil from the ground….

White people started it, but there is no shortage of non-whites following their example.

And could it be there is… a common factor… not based on ascriptive identity? Nah!

That’s sooo hard to think of..

While the ide of a knobbly savage is much more romantic, attractive and what have you.

Yeah, you have a retired lawyer in the house. I am an inactive member of the California Bar, I practiced from 1980-1995 until I reached a point where I couldn’t stand doing it for one more minute, so I mailed the postcard to the Bar going inactive. My practice was a lot of divorces, real estate (for four years, I was also a licensed broker, several classic stories, it’s a lot harder than it looks), general business stuff and odds and ends…

After that, I co-founded several tech startups with a friend/bizbuddy/former client and his wife. I was the word guy, they were the tech guys. I didn’t make a whole lot of money doing this, but I learned a hell of a lot, and I take satisfaction in one thing: I am the oldest of three brothers, and my companies made more money than the middle brother’s company did.

After we crashed the tech market, I fled to Oregon in 2001. I soon became embroiled in public controversy regarding our electric utility cooperative, and I founded a nonprofit mutual benefit corporation for the specific purpose of causing a regime change in the coop, and it did so in a most amazing spectacle. Perhaps as a result of that, in 2007 the council of a small city 11 miles south of me appointed me muni court judge, which was half an hour a month on average of speeding drivers and loose dogs, and that went on for ten years…

I am also notorious among the staffers at the Public Utilities Commissions of two states because mandatory arbitration clauses are one of my pet peeves…

I am aware of Juliana and am watching it closely. I am rooting for the plaintiffs, but they will need to do something legally unprecedented in order to win. As you know Bob, the US government is like Cerberus, there’s a legislative head, an executive head and a judicial head. Long-term, complex policy formulation and execution are typically the province of the first two heads, and the first head is the one that appropriates money. The Constitution limits the third head to “real case or controversy”, this clause has been extensively litigated before SCOTUS over the years, and there is general consensus that courts don’t have the tools, the knowhow, the competence, the backing of our citizenry or anything else with which to handle a problem of this nature and magnitude.

> that courts don’t have the tools, the knowhow, the competence, the backing of our citizenry or anything else

Hmm. Have they no way to delegate? Courts have managed systems before, e.g. school and prison systems under court order. I grant the scale is different.

The Canadian / Quebec case was decided against the petitioners, mainly on procedural issues. They intend to appeal.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/class-action-climate-change-young-quebecers-rejected-1.5213325

Justice Morrison wrote a 25 page decision which started with (translations are mine, the decision is in French):

“The exclusive jurisdiction to hear class actions is procedural and not substantive in nature.”

He decided the case on the definition of who were members of the class seeking to be certified and found that it was too arbitrary (you can’t include people under 18 since they haven’t reached majority, and why an arbitrary cut off age of 35 and not 40, etc.). He was analysing the application of article 575 of Quebec’s Code of Civil Procedure dealing with the certification of class actions.

But he ended his decision with this:

“Given that another remedy may be possible, the Tribunal is of the view that it would be inappropriate to comment further on the other criteria applicable under section 575 CPC, particularly whether the facts alleged appear to justify the conclusions sought, including the question of punitive damages.”

Thanks for this. I wonder why the parallel case in the Netherlands was a win, and this is a loss.

The clearest difference seems to be procedural.

In Quebec, the group Environment Jeunesse tried, and failed, the first step of certifying a group for a class action.

In the Netherlands, Urgenda signed up 886 people and sued on its and their behalf using the tort law of negligence.

Article 21 of the Dutch Constitution, provides that “[i]t shall be the concern of the authorities to keep the country habitable and to protect and improve the environment,…”

The Dutch Civil Code states that the party who commits a tort towards another is obligated to compensate the losses, which the other party suffers as a result. In order to succeed, an action on grounds of a tort must meet five requirements: unlawfulness, attributability, loss, causality and relativity.

Here’s an analysis of the first court’s decision by Eleanor Stein of Albany Law School and the State University of New York, and Alex Geert Castermans, of Leiden Law School (Netherlands):

https://www.mcgill.ca/mjsdl/files/mjsdl/6_stein_web.pdf

And an analysis of the Court of Appeals decision by Jonathan Verschuuren, Professor of International and European Environmental Law at Tilburg University:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/reel.12280

In which he mentions:

“the Hague Court of Appeal noted that causality is less of an issue when the matter of the dispute is not the award of damages.”

And an analysis of the application of Urgenda to U.S. law and Juliana, in particular:

https://harvardlawreview.org/2019/05/state-of-the-netherlands-v-urgenda-foundation/

Lorenzo Squintani explains that there have been a number of other cases brought using the same procedure and arguments in the Netherlands following the first Urgenda decision. They concerned air quality. One was successful, the other wasn’t.

Tort-Law based Environmental Litigation: a Victory or a Warning?:

https://brill.com/view/journals/jeep/15/3-4/article-p277_277.xml

In the Urgenda case, the latest appeal to the Supreme Court, was heard May 24, 2019. As a court of cassation it does not re-examine facts, it will interpret the relevant law.

The Court of Appeal took five months to issue its decision after hearing the appeal.

So basically a lawsuit against the People … in that the government is of the People. Such a lawsuit can’t be enforceable, because self referential. Otherwise it would be possible to have a lawsuit against the government over Vietnam or any of our other government led foreign interventions where innocent civilians are directly killed. Not just inconvenienced through indirect modification of the weather (the human part anyway).

This would constitute revolutionary change using the courts, that goes well beyond the usual balancing of the three parts (which is intended to balance the government not abolish it). A secular version of the Iranian revolution, where the courts completely suppress the Executive and Legislative branches, necessarily with the acquiescence of the military.

False. The government is not the People due to principal-agent problems. There is a vast literature on this topic.

What is, in your view, the difference between a lawsuit trying to stop an illegal waste dump and a lawsuit trying to stop an illegal war, as long as both are illegal under the relevant national laws?

In case of a war the negative effects are usually a lot more obvious and certain while the government clearly acts in the name of the nation, which should be enough to have grounds to sue for every citizen. I’ll grant you that once the killing starts a lawsuit to stop the war will be alot more difficult – but that is a practical not a legal issue.

In civil suit, one part of the People can sue another part of the People. And of course the government (the People) can act against a part of the People. Part = individual, corporation, state etc. The civil judicial government (tort law) exists to provide redress of part against part. When the government acts against an individual or part of the People, that is criminal law, not civil law. A whole can’t act against a whole (act against itself), and a part can’t act against a whole (sue that which makes the law).

What I interpreted in the suit, was an attempt to get the government to act against itself (hence Judiciary against the other two branches) outside constitutional provisions. I might be wrong, but what I saw was an revolutionary attempt at Judicial supremacy (a secular Iran).

“I might be wrong”.

You are, of course, correct. You are wrong.

In Canada, like most countries, there are any number of examples of a single person or a group suing the Government (the Canadian Crown).

For example, a recent Federal Court class action lawsuit based on allegations of gender and sexual orientation-based harassment and discrimination and sexual assault within the RCMP. The Government settled for $100 million.

In 2018, the Federal Court of Canada approved a settlement for Canadians who were persecuted or fired due to their sexual orientation while in the Canadian Armed Forces. The settlement could reach $145 million.

Maher Arar “was detained during a layover at John F. Kennedy International Airport in September 2002 on his way home to Canada from a family vacation in Tunis. He was held without charges in solitary confinement in the United States for nearly two weeks, questioned, and denied meaningful access to a lawyer.” He was deported not to Canada but to Syria where he was tortured (according to a Commission of Enquiry set up by the Canadian government). He was eventually returned to Canada. He received $10.5 million and an apology from PM Stephen harper for Canada’s participation in his ordeal.

In 2008 the Government paid $31.3 million to three men wrongfully linked to terrorism and then tortured in Syria. “A 2008 federal inquiry found the actions of Canadian officials contributed indirectly to the torture of three men.”

Omar Khadr sued the Government of Canada for not protecting his rights while he was being tortured by the U.S. in Guantanamo. The Government of Canada settled for $10.5 million.

If this is a lawsuit against the people, isn’t every lawsuit against the USG for reparations, damages, etc. a lawsuit against the people?

Yes. And good luck with that. Did Vietnam or some of the Vietnamese people sue the whole US for damages?

No, but U.S. citizens have successfully sued Iran for the 9/11 attacks, and for the Beirut bombing of Marine barracks in 1983.

“A judge in the US has issued a default judgement requiring Iran to pay more than $6bn to victims of the September 11, 2001 attacks that killed almost 3,000 people, court filings show.” The case is Thomas Burnett, Sr et al v. The Islamic Republic of Iran et al.

And in 2016 “The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on April 20 that nearly $2 billion in frozen Iranian government funds must be turned over to injured survivors and families of Americans killed in the 1983 bombing of the U.S. Marine Corps barracks in Beirut and other attacks for which Iran was found liable by U.S. courts.”

Great overview.Thanks very much, Lambert.

The question of whether a victory for the plaintiffs in Juliana would have any meaning in the real-time world of policy hinges on the question of the solidity of the principle of the rule of law. There has been a trend away from maintaining this principle, particularly in the United States. As most illustrative, I recall Obama and the “Let’s look forward, not back” speech and it’s inevitable effects – the release of everything from war criminals to aid scammers from the threat of prosecution.

The statement seems to me to be blatantly in contravention to any principle of the law as truly “The law of the land” Even the president can’t arbitrarily set aside the power of the law to act.

But he can. And did.

Such statements and incidents have nibbled away at the power of the structure that could support any SCOTUS ruling in the Juliana matter, leaving the broken remains as rubble to be walked over by our current president.

Today, when corporations obtain a judgement , for example, on the legality of crude oil pipelines and the resistance to them, they enforce it with their own forces.

So the underlying question I’d like to see discussed in depth here is- can any court enforce any major decision opposed by any of the heavies–a huge corporation, the military, the executive, etc. ad nauseum?

The answer to that question will determine whether a decision supporting the plaintiffs would have any meaning. Or has the court system, in it’s relationship to the powerful, decayed away to theatre?

> The question of whether a victory for the plaintiffs in Juliana would have any meaning in the real-time world of policy hinges on the question of the solidity of the principle of the rule of law.

(Thank you.) I didn’t work this in, but the behavior of the Federal Government reminds me of the behavior of the tobacco companies, and a wave of public revulsion did enable not only change in the law but the rule of law to operate.

Q: How do you get a Climate Crisis Denier to change his mind on Global Warming?

A: Tell him it causes Autism. Problem solved.

So, in classic US style, a critical constitutional change will ultimately depend on a creative re-interpretation of everything. See 1804, 1828, 1864, 1896, 1936, 1954…

The crucial part to make such a change succeed is that it has to cover a real political change — that in fact, real elite and popular movements are threatening to overthrow the system (see 1864 for the sharpest example) and the courts are in the position to elide the issue by pretending to act as an interpretative body.

Good luck! If it works, it’s critical, even if I would like to see a system where the political is a bit more explicit and work through shifting coalitions rather than slight of hand. But the consequences are too dire to be squeamish.

“So, in classic US style, a critical constitutional change will ultimately depend on a creative re-interpretation of everything.”

By a tiny handful of people whose professional expertise is convincing a dozen or fewer people with no relevant (to the issue being considered) expertise that they have a more effective argument about the meaning of a few words, reality notwithstanding.

That’s always struck me as one of the more irrational parts of the us political/legal system.

A few corrections to this piece:

1.) Original complaint was filed August 2015

2.) piece accurately quotes American Bar Association article, but that article falsely characterizes the case as asking the court to “order the federal government to act on climate change.”

3. ) Vic is quoted as saying that the suit demands “that the legislative system and the executive system have to work together in order to come up with a plan that would draw down carbon emissions to a point that’s sustainable for human life.” I’m sure that’s an accurate quote of what Vic said, but the suit does not demand any action from the legislative branch.

4) The story quotes from a Forbes article and suggests that the standing arguments and facts in Juliana and Clean Air Council are similar or identical, but there are many important differences. The Clean Air Council Plaintiffs challenged the rollback of existing environment regulations, not the historic and ongoing affirmative actions of the federal government in contributing to climate change. They also challenged budget cuts and appointment and hiring and firing decisions that had speculative effects, if any, on climate. Here is what we said in our briefing on this:

“the Eastern District of Pennsylvania found “much of the challenged conduct does not contribute to greenhouse gas emissions” and the district court was left to “speculate as to what actions the Federal agencies and the fired personnel would have taken but for the budget cuts or firing decisions.”. . . Judge Diamond’s opinion in that case turns fundamentally on the absence of a plausible causal nexus between the plaintiffs’ injuries that were sustained in 2011 and conduct that began in 2017. Clean Air Council *6. Here, Plaintiffs challenge Defendants’ historic and ongoing conduct causing existing and ongoing harms.”